Idu Mishmi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

In brief

A

Idu Mishmi is a tribe from Arunachal. They largely stay around the Dibang valley.

Most Idu Mishmis are Hindus and there is a belief in the tribe that Rukmini was from their community.

B

Estimated Global Speakers: 28,000

People Groups Speaking as Primary Language: 2

Scripture Status: New Testament

●●●●●

| 1 | People Group | Country | Country Population |

Global Population |

Indigenous | Progress Scale |

Primary Religion | % Christian Adherent |

% Evangelical |

Est. Workers Needed * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Idu | India | 32,000 | 42,000 | ● | ● | Hinduism | 5.16 % | - | |

| 3 | Lhoba, Idu | China | 10,000 | 42,000 | ● | ● | Ethnic Religions | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 1 |

| 4 | Totals: 2 | 1 ● | 1 |

- An estimate of the number of pioneer workers needed for initial church planting among unreached people groups by country. Estimates are calculated only for unreached people groups and are based on ratio of 1 worker for every 50,000 individuals living in an unreached people group by country. Some workers may already be onsite. Many more workers are needed beyond this initial estimate.

The community

LOWER DIBANG VALLEY DISTRICT- Government of Arunachal Pradesh

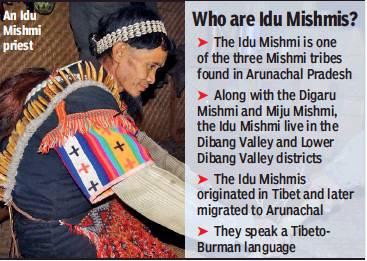

The IDU-MISHMI is a major sub-tribe of Mishmi group. Their brethren tribes are namely the DIGARU-MISHMI (TARAONS) and the MIJU-MISHMI (KAMANS). They inhabit the Lohit district, Dibang Valley district and Lower Dibang Valley district. They are of mongoloid stock and speak the Tibeto-Burman language.

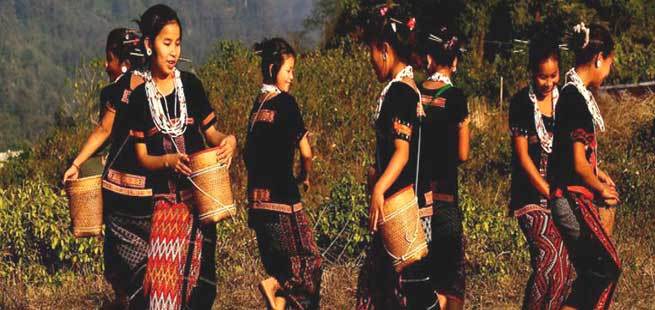

The Idu Mishmi is one of the two major tribes of the district. The Idu Mishmis can be distinctively identified among other tribal groups of Arunachal Pradesh by their typical hairstyle, distinctive costumes and artistic patterns embedded on their clothes. People of sober nature still maintain deep-rooted aesthetic values in their day-to-day life with great pride and honour. All pervading goddess Nani-Intaya is the sole creator of the universe for the Idus.

The Idus have their distinct dialect, which falls under the Tibeto-Burman group of languages. Traditionally, Idus believe in animism. They worship several benevolent and malevolent spirits. Nani-Intaya and Masello Zino are worshipped as creators of mankind and universe as a whole. Mythological characters like SINE-RU a first IGU (Idu Priest) still holds high place and reverence in the minds of the people. The prints of his palm on the huge rocks at Athu Popu near Keyala Pass in Dibang Valley district on China border, is supreme and holy shrine. The major festivals of the Idus are ‘Reh’ and ‘Ke-meh-ha’. Reh festival is held during the month of February. It is an occasion for people to relax, enjoy, dance, eat and drink.

The Idus are expert craftsman. The Idu women, in particular, are very good weavers. Their great aesthetic sense is well reflected in the exquisite designs created on the clothes produced on handlooms. The Idu men are well apt in making beautiful basketry items of bamboo and cane.

A well-developed civilization dated back in the pages of history can be found in the region. Remnants of 10th Century AD found at Bhismaknagar, Chidu & Chimri villages in the lower belt of the district prove that the Idus coexisted with great harmony with the people of plains and adjoining states.

Migration

Apparently the Idu-Mishmis migrated towards the south to present habitat from Tibet through Dibang and Lohit Valleys. Some of the prominent migration points from the Tibet indicated by the ancestors are – (i) ANDIKU – the direction towards North-Pole Star, (ii) ASE-ALE – the course of Lohit river and (iii) INNI LON PON – the region where the first rays of the sun falls. There are about seventy-six clans. Some clan counts their genealogy up-to about twenty-eight generations.

Birth Ceremony

Idus believe that to have pregnancy is a great blessing of the Divine mother “INNI MASELO ZINU AYA” or Sun Goddess. After pregnancy is noticed, two cocks are tamed as sacrificial bird to offer their blood to beneficent and maleficent spirits at the time of birth ceremony for the welfare of newborn. During pregnancy the couple follow some taboos. They should not utter any abnormal outcries of birds and animals or imitate the activities of handicap persons, or kill snakes, or offer any kind of articles for burial in the grave, since the exercise of above activities is supposed to lead to deformation of the child at the time of delivery. Food and rice beer is stocked before three to two months ahead for consumption during taboo days. On delivery of the child, the father puts a bunch of shrubs at the entrance gate of the house and goes to jungle to collect the elephant grass-EPONTOH and RONTHEPA- a creeper of thorn species. He places them over the entrance of the room for protection of evil spirit and for welfare of the child. A well versed in hymn and experienced priest is invited to perform A-TA-YE- a ritual ceremony. He propitiates the INNI MASELO and other beneficent and maleficent spirits of parent and grant-father and mother of the child and appeases them with the blood of sacred cock and water adulterated with rice beer.

The members present on the occasion are entertained with food and drink and they abstain from doing hard work for one night. The name of child is decided within five days. Main taboo remains for six to nine days. The parent including members of the house should not do any hard work like cutting with axe, digging of earth, killing of wild animals, touching of poison or irritating objects. Purification of taboo called ANGI ATHON NU is held again one day within the period in between six to nine days with the help of priest. Ritual ceremony is performed as that of A-TA–YE. On this day food and drink are prepared on large scale for entertaining the invitees.

Marriage Ceremony

The Idu-Mishmi society is patriarchal and patrilineal. The property is inherited by the son from the father. The Idu–Mishmis used to practice polygamy, but incestuous marriage is prohibited.Marriage be have through elopement and abduction but the most preferable one is by negotiation or arranged marriage. The younger or elder brother can marry the widow of his deceased brother. A man may marry his step-mother (other than his mother’s sister) after the death of his father. If the step-mother refuses to remarry, she or her parent or guardian has to pay back the bride price. To marry a girl it involves a huge expenditure in cash and kind for the bride price.

Construction of House

An Idu-Mishmi house is a long one like a bus, rectangular size raised above two feet from the ground and supported on wooden posts usually accommodate a joint family. Bamboo, cane, wood and leaves of toku and straws are used for construction. The front is an extension of roof with ground floor to keep the

domesticated animal and next to it is a small veranda/corridor made of bamboo or plank for stepping up from the ladder to enter into house. A house may have a number of rooms with partitioned as per strength of the family members. There is a straight corridor/passage. Each room has a hearth and is used for both cooking and sleeping. The serial allocation of room consists of male room, which is called AGRAH. There may be passages in between two rooms for latrine and husking of paddy. Each room has one window towards the poultry yard and pigsty under the house.

Cultivation and Food Habits

The Idu-Mishmi practice both terrace and wet rice cultivation. Rice, Maize and Millet are the staple food of the Idu–Mishmis. Sweet potato and different kinds of Arum and vegetable are the usual crops. Their main meal is taken twice a day. They are fond of fish and meat. They preserve food by smoking and drying over the fireplace. The home brewed rice beer (YU) is quite popular.

Education

Modern education had a late start among the Idu Mishmis as they didn’t have early contact with the British colonizers. But educational institutions and literacy have multiplied rapidly since independence.

Economy

Idus are expert in handicraft and weaving.

The man makes basketry items out of cane, bamboo for household. The women weaves cloth with different design on both ETONWE (coat) & THUNWE (shirt). Many Idus purchase tractors and other machinery equipment for cultivation of cash crops like ginger, mustard seed and other cultivation of fruits (orange, pineapple, pears etc.), tea and paddy etc. Many literate men and women have joined government jobs, while others also undertake contract/supply works in various departments for earning their livelihood.

Death Ceremony

To die at the old age is treated as normal death but if it is accidental or premature, past acts of the deceased are supposed to have indirect effect. When a person is dead the entire village undergoes taboo for five days. During period of taboo, one does not undertake any new construction work, agricultural activities, fishing, hunting and weaving. The location or house where dead body is kept said to have been origin of taboo, so one can go there but before coming out of house or premises of taboo one must attend the purification ritual of the priest to continue normal life.

They bury their dead body along-with all movable articles. One day before of burying the dead body a well-versed and experienced priest is called to perform ritual ceremony for negotiating with the departed soul! The ritual ceremony is performed according to capability of deceased family members. If there is no custodian of the dead body, purification ritual is held for only two to three hours. The ritual ceremony of BRONCA is held for two days and AYA for four days, which involves a huge expenditure in cash and kind. The kith and kin contribute for burial ceremony. All the movable articles, irrespective of their cost/price, which belonged to or were liked by the deceased, are buried. Hence the burial is quite akin to the old Egyptian Pyramid traditions, except that burial among the Idus requires digging of sufficient rooms for the deceased and his articles.

Festivals

Reh

January 31, 2017: Arunachal24.in

From: January 31, 2017: Arunachal24.in

Reh is one of the most important festival of the Idu Mishmis who believe that they are the children of the divine mother ‘Nanyi Inyitaya’. None can get her blessings and keep alive the bond of brotherhood and social feeling strong, unless one performs the puja or celebrates the Reh festival.

The Reh festival is generally celebrated for 3 days from 01st to 03rd Feb every year. The first day is called ‘Andropu’. It is observed by offering prayers so that the festival may pass off smoothly. The mithuns are brought and tied near the house. The ‘Naya’ dance is held during the night. Eyanli is the second day and may be termed as the killing day of animals such as Mithuns and buffaloes. The guests are entertained with rice, meat and rice beer. The third day is called ‘Iyili’ and on this day heavy feast is arranged and everybody is entertained. Presents of meal-rice are also supplied to the neighbouring villagers who fail to come to the festival.

The festival requires a number of sacrificial buffaloes for offering to the great mother ‘Nanyi Inyitaya’. Presents such as money in cash and pigs are given to the relatives.

The festival being very expensive, all arrangements and preparations for the festival have to be made four or five years before the actual celebration of the festival. As such a person wanting to celebrate this festival has to take resort to the system locally called ‘Ada’ which is nothing but collection of mithuns, pigs, cash, money etc., even by way of loan from others. When ‘Ada’ is completed a tentative year is fixed about one year ahead of the actual celebration. The preparation of rice beer in large scale locally called ‘Yunyiphri’ is under taken, three to four months before the actual celebration.

After all necessary arrangements and preparations are made, ‘Tayi’ a form of calendar is served to all kith and kin as an invitation to come to the celebration on scheduled dates. The ‘Tayi’ is counted by knots on a string and each knot is cut off as a night passes on, one after another. The invited kith and kin arrive at the place of celebration when two knots remain on the string.

The Reh festival is celebrated for 6 days. The first day is called Andropu’. It is observed by offering prayers so that the festival may pass off smoothly. The mithuns are brought and tied near the house. The ‘Naya’ dance is held during the night. Eyanli is the second day and may be termed as killing day of animals such as mithuns and buffaloes. The guests are entertained with rice, meat and rice beer. The third day is called ‘Iyili’and on this day heavy feast is arranged and everybody is entertained. Presents of meal-rice are also supplied to the neighbouring villagers who fail to come to the festival.

Ilyiromunyi is the fourth day of the festival. There is not much feasting on this day. The priest only performs the rituals in favour of worshiper for bestowing upon him wealth, all round prosperity and for general well-being. Omen is observed by pouring ‘Yu’ rice beer into the ears of a pig, bound and laid on the ground. If the pig does not fidget, it is considered evil and result in bad crops, epidemic etc otherwise it is good.

The fifth day is called Aru-Go. On this day the remaining food stuff and other drinks are prepared for the feast and taken with co-villagers. The sixth day is the concluding day of the festival is known as ‘Etoanu’. On this day the blood smeared seeds are sown in the fields and rice beer is poured at the trunk of the stump for the goddess of the house hold.

History

Was Rukmini an Idu Mishmi?

Written by Adrija Roychowdhury, March 29, 2018: The Indian Express

Indeed, a mythological tale floats around the lands inhabited by the Idu Mishmi tribe that claims to be associated with the Krishna-Rukmini legend. To what extent it is rooted in Hindu mythological traditions is a far more complicated matter.

Rukmini, Rukmini in Arunachal Pradesh, Madhavpur mela in Gujarat, Vijay Rupani, Mahesh Sharma, Gujarat, North East, Arunachal Pradesh, Krishna, Krishna Rukmini legend, India news, Indian Express Popular knowledge of the Krishna-Rukmini mythology states that Krishna, who is believed to have established his kingdom at Dwarka in Gujarat, married Rukmini. (Wikimedia Commons) At the ongoing Madhavpur mela at Gujarat, attended by a large number of ministers from the North East, BJP politicians Vijay Rupani and Mahesh Sharma remarked that the Hindu God Krishna’s wife Rukmini traces her roots to the Idu Mishmi tribe of Arunachal Pradesh. In the process of retelling a popular Hindu mythological tale, they both were clearly attempting to create an important historical linkage between Gujarat and the North Eastern state. Soon After, #EkBharatShreshtaBharat (one India, ideal India) started trending across social media.

While we are yet to tell what the political motivation could be of the statement made by the two ministers, it might be useful to reflect upon whether at all there is any grain of truth in the remark. Popular knowledge of the Krishna-Rukmini mythology states that Krishna, who is believed to have established his kingdom at Dwarka in Gujarat, married Rukmini, believed to be an incarnation of Lakshmi and born to the king of Vidarbha kingdom that was located in what is now Central India. However, digging through academic work on the tribes of Arunachal Pradesh and tribal folklore of the region would reveal that Rupani and Sharma are not wrong when they trace Rukmini’s roots to the state. Indeed, a mythological tale floats around the lands inhabited by the Idu Mishmi tribe that claims to be associated with the Krishna-Rukmini legend. However, to what extent it is rooted in Hindu mythological traditions is a far more complicated matter.

What is the myth of Krishna-Rukmini among the Idu Mishmi tribe of Arunachal Pradesh?

The Idu Mishmi are a tribal ethnic community located in Arunachal Pradesh and Tibet. According to folktale specialist Praphulladutta Goswami, the Mishmis “trace their ancestry to Rukhmavir, elder brother of Rukmini, to carry off whom Krishna came all the way from Dwarka in Gujarat.” Goswami goes on to explain that among these people there exists a springtime love song in the local language that refers to Krishna and his abduction of Rukmini.

“Dear Remseiba, Srikrishna of Mathura carried off Rukmini;

I have not gone to carry you off. Even then you do not care for me.”

Rukmini, Rukmini in Arunachal Pradesh, Madhavpur mela in Gujarat, Vijay Rupani, Mahesh Sharma, Gujarat, North East, Arunachal Pradesh, Krishna, Krishna Rukmini legend, India news, Indian Express The Idu Mishmi are a tribal ethnic community located in Arunachal Pradesh and Tibet. (Wikimedia Commons) Reportedly, dances and plays of ‘Rukmini haran’ are common among the members of the tribal community. It is noteworthy that a local nomenclature applied to the Idu Mishmis is that of “chulikata” (chuli-hair, kata- cut). The name is derived from a mythological saying that Krishna asked them to cut their hair as a punishment for not allowing him to marry Rukmini.

“There is a myth and there is a fort and a town called Bhismaknagar associated with Rukmini. But all of these are myths and you can’t prove a myth. Maybe its part of earlier linkages with Assam which created this story or maybe it’s a creation of regional imagination,” Jumyir Basir, Professor of Tribal Studies in Rajiv Gandhi University at Itanagar, told indianexpress.com.

How should we read the myth’s presence in modern times?

Professor Basir explains that the myth of Krishna-Rukmini in Arunachal Pradesh needs to be read in the same way we read variants of the Mahabharata. “The Mahabharata also exists in different forms. There is a Tamil Mahabharata which is very different from the one in the north. There is an Assamese Mahabharata and a Bengali one and all of these bring their entire region with their entire story,” she says. Therefore, the Krishna-Rukmini legend among the Idu Mishmis also needs to be understood as a regional variant of a popular piece of mythological literature.

However, it is also interesting to note how a tribal community has absorbed a Hindu mythological tradition. Explaining the way different religious and cultural systems interact with each other in any social context, Professor of Tribal Studies M C Behera writes in his work that “syncretic traditions have been in existence in many communities of Andhra Pradesh”.

For instance, while most among the Khasi tribe in Shillong are Christians, they still believe in the snake God, U Thlen. In Western Assam, Hindus and tribes, alike worship the snake Goddess Manasa in the rainy season. Similarly, another tribal community of the North East, the Syntengs is believed to have been worshippers of the Hindu Goddess Shakti.

The Idu Mishmi tribe are followers of animism. In other words, they are believers in the religious system that worships plants, animals and inanimate objects. Professor Basir says there has not been much absorption of Hindu traditions among most of the tribes of Arunachal Pradesh because they have their own form of animistic belief systems. However, most of these animistic belief systems can be associated with Hinduism. “For example, most of the communities believe that Banyan and peepal trees are the abode for spirits. So it’s very easy to link it with Hinduism because Hindus also revere the Banyan and Peepal trees but the belief system is different. We feel that most of these spirits are malevolent rather than benevolent and we don’t pray to these trees,” she says. She explains that over time with the institutionalisation of religious practices among the tribes, a mixed form of religion exists among most tribes.

The animistic Idu Mishmi tribe too has absorbed parts of Hindu mythological traditions, to an extent that they trace their origin to the Krishna-Rukmini legend. The myth in Arunachal Pradesh, therefore, needs to be read as a syncretism between local tribal tradition and a popular mythological telling.

Tigers

Conserving tigers the Idu Mishmi way

The Idu Mishmis Bat For A ‘Cultural Model’ Of Conservation

As conservationists and wildlife authorities grapple with the issue of man-animal conflict around sanctuaries and nature reserves, a tribal community in Arunachal Pradesh is championing a unique ‘brotherhood’ they say helps save the tiger.

The Idu Mishmi community in Arunachal’s Dibang Valley considers tigers to be “big brothers” and holds that killing the big cat amounts to “homicide”. This, they believe is a “unique conservation strategy”, which helps the big cat population to thrive in the area. But lately, the leaders of the community are worried as the area has come under the spotlight with the state forest department planning to declare the area a tiger reserve.

At the heart of the debate between the forest department and one of the smallest tribes in Arunachal lies a significant question: What constitutes good conservation technique?

The presence of tigers in the community forest came to light recently following a camera-trap report of the Wildlife Institute of India (WII). The report notes the presence of tigers at 3,630 metres – the highest in the eastern Himalayas — and says the Mishmi hills have more tigers than the designated tiger reserves of the north-eastern state. This has prompted the government to propose that the 4,149-sq.km Dibang Wildlife Sanctuary (DWS) be declared a tiger reserve.

The Idu Mishmis, however, have contested the government’s ‘one-size-fits-all’ conservation model. They claim it is their cultural belief and practices that have led to a healthy population of tigers in the Mishmi hills. They argue the ‘indiscriminate’ notification of reserves and sanctuaries would harm the community, and consequently, the tiger population.

The Idu Mishmi Cultural and Literary Society (IMCLS) recently wrote to the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), saying the cultural practices of the community should be given more importance than any proposal to declare the DWS a tiger reserve. “We believe that just because tigers are ‘discovered’ in a place does not mean that it should be notified as a tiger reserve. There should be an understanding of how and why those tigers have survived in that place,” IMCLS president Ginko Lingi wrote to NTCA.

The IMCLS said Dibang valley called for a ‘new kind of tiger reserve’, to be built around the ‘cultural model’ to help the tigers thrive.

It also pointed out that the WII report did not mention how many tigers were photographed inside the DWS and how many outside. The report said 11 tigers were identified during the camera-trap exercise conducted between 2015-2017 across 336 sq.km of the DWS. In its letter, the IMCLS quoted the findings of Delhi-based ecologist-anthropologist, Sahil Nijhawan, who had conducted a similar exercise in 2013-2015 and had found that the tiger density in community-owned forests was 4.5 times higher.

Ambika Aiyadurai, an expert on the community and a teacher at IIT Gandhinagar’s department of humanities and social sciences, said the government should take the local community into confidence before taking a decision on the DWS.

Arunachal’s principal conservator of forests Ravindra Kumar told TOI that his department had begun consultations with the local community after the NTCA sought a proposal from the state government for declaring DWS a tiger reserve. “The advantage of declaring the DWS a tiger reserve is that it will not only increase the flow of funds for conservation, but also help the local community by opening up employment opportunities,” Kumar said.

Suicide

High suicide rate

US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health

Abstract

Introduction

Suicide is a spectrum of behavior including suicide ideation and suicidal attempt and is undoubtedly the outcome of the interaction of several factors. The role of two main constructs of human nature, aggression and impulsivity, has been discussed broadly in relation to suicide, as endophenotypes or traits of personality, in research and in clinical practice across diagnoses. The objective of our study was to assess impulsive and aggressive behaviors among primitive people of the Idu Mishmi tribe, who are known for high suicide completer and attempter rates.

Methods

The study group was comprised of 177 unrelated Idu Mishmi participants divided into two sets: 39 suicide attempters and 138 non-attempters. Data on demographic factors and details of suicide attempts were collected. Participants completed a set of instruments for assessment of aggression and impulsivity traits.

Results

In the Idu Mishimi population we screened (n = 177), 22.03% of the individuals had attempted suicide, a high percentage. The suicide attempters also showed a significant sex difference: 35.9% were male and 64.10% were female (p = .002*). The suicide attempters (A) scored significantly higher than non-attempters (NA) on aggression (A = 23.93,NA = 18.46) and impulsivity (A = 75.53,NA = 71.59, with p value = 0.05). The trait impulsiveness showed a significantly higher difference (F (1, 117) = 7.274) in comparison to aggression (F (1, 117) = 2.647), suggesting a profound role of impulsiveness in suicide attempts in the Idu Mishmi population. Analysis of sub-traits of aggression and impulsivity revealed significant correlations between them. Using different models, multivariate logistic regression implied roles of gender (OR = 1.079 (0.05)) and impulsiveness (OR = 3.355 (0.013)) in suicide attempts.

Conclusion

Results demonstrate that gender and impulsivity are strong risk factors for suicide attempts in the Idu Mishmi population.

Introduction

Many attempts have been made to define the complex behavior of suicide. A number of predictors have been implicated in suicidal behavior from different social, psychological, and biological dimensions. Across cultures, the most robust findings in suicide research are the differences between genders and age groups [1]. The most dramatic increase overtime in suicide mortality rate has been observed in the third world countries India and China, due to their unique socioeconomic and behavioral patterns [2]. Current research indicates that the presence of psychopathology is probably the single most important predictor of suicide and approximately 90% of suicide cases meet criteria for at least one psychiatric abnormality [3]. The high prevalence of psychiatric disorders among suicide deaths and attempts has been observed and implicated as one of the best indicators of complex suicide behavior [4][5]. JJ Mann et al. (2003) proposed the stress-diathesis model to investigate the role of other factors over and above psychopathology [6]. Two main constructs of human nature, aggression and impulsivity, have been discussed broadly as endophenotypes or traits of personality, in relation to suicide, in research and in clinical practice across diagnoses [7, 8, 9]. Previous studies have established them as risk factors for suicide but it remains uncertain whether their effect on suicide is cumulative or independent. Current research indicates that the overlap between these constructs is robust, and they should be considered together, as a single “Impulsive-Aggression” phenotype [10]. However, other viewpoints emphasize their distinct latent dimensions [11].

Aggression refers to a wide spectrum of behaviors. It is an action intended to harm and identifies people who are predisposed to involve physical punishment, restriction, or verbal attacks like insults, threats, and sarcasm in actions or situations that are aversive or stressful [10]. It has been associated with suicidal behaviour in previous clinical, epidemiological, and family-based studies [12].

Impulsivity is a prominent construct of personality and embraces a multitude of behaviors that include responding prematurely, before considering the consequences, or action without foresight, poor planning, impaired self-regulation, sensation seeking, inhibitory control, risk taking, and preference for immediate over delayed rewards [13,14,15] that normally result in undesirable or deleterious outcomes. It is an adaptive dimension of personality and believed to stem from deficits in the self-regulation of affect, motivation arousal, working memory, and higher order cognitive functions [16]. Other abnormal behavioural manifestations of impulsivity have been found in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), addictions, and violent criminality, as well as antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), borderline personality disorder (BPD), and intermittent explosive disorder (IED) [17].

Studies assessing the prevalence of depressive traits have also found that attempters are more likely to be impulsive and aggressive [18]. Further, some have postulated the role of impulsivity in nonlethal suicide attempts or suicide gestures [19] and others found that the act of completed suicide is often not made impulsively [20].

The idea of an impulsive attempt, an attempt that is abrupt or that lacks planning, has been mentioned in the literature since at least the nineteenth century [21], and over the last decade research stirred by this idea has increased markedly [22]. In this line of thought, ethnographic accounts and monographs published by anthropologists highlight the presence of impulsivity and aggression, and their correlation, in indigenous people [23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. The presence of high rates of impulsivity and aggression in Indian tribes has also been discussed [28, 29, 30, 31]. Further, some ethnographers and scholars have mentioned the Idu (Choolkatta) as a warrior-like, aggressive, comparatively offensive, and barbaric clan of Mishmi [32, 33]. The Idu Mishmi, a Tibeto-Burman speaking tribe is the largest subgroup of Mishmi located in the Dibang Valley and Lower Dibang Valley districts of Arunachal Pradesh. It is a major sub tribe of Mishmi tribes of Arunachal Pradesh along with the Misu and Digaru Mishmi. The Idu population is distributed in about seventy-six clans and holds a distinctive identity due to their typical hairstyle, unique costumes, and the artistic patterns emblazoned on their cloths. They practice animism and souls for all activities are defined. They are mainly engaged in agriculture and its allied activities for their livelihood but the practice of hunting is still prevalent in the society.

The objective of our study was to assess personality traits, specifically impulsive and aggressive behavior, among the primitive people of the Idu Mishmi who are known for high rates of suicide completers and attempters [34, 35]. The present study could be apprehended as an attempt to observe a less-studied association between personality traits and suicide attempts in a high suicide risk solitary population. Our investigation of aggression, impulsivity, and suicide attempts in light of demographic factors will contribute knowledge to suicidology, toward a more comprehensive image of how these personality traits impact the risk of suicide across genders in the general population.

Materials and methods

The study design of the present study is cross-sectional and the data set is comprised of 177 Idu Mishmi participants, of both sexes, aged 15–70 years (data in S1 Text), from families known to be suicide affected and un-affected, from Anini town, in the Dibang Valley district (altitude 1,968 m or 6,457 ft), Arunachal Pradesh state, India. Data were recorded using closed questionnaires and well-validated psychological tools in 30-minute-long, face to face, structured, in-depth interviews, after obtaining written consent. Participation was voluntary and no compensation was given to study participants. Demographic details including age, sex, marital status, education, and employment were collected by structured questionnaire. A psychiatric diagnosis of suicide attempts was based on the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). Assessment of personality traits, aggression and impulsivity, was performed using the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) and Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, 11th version (BIS-11) respectively. All the employed tools were used after pilot testing them in the Idu population and no modification was made to the schedules. Each participant’s responses were recorded in their preferred language (Hindi or English) by a trained anthropologist (PKS), as the population is multilingual.

The schedule C-SSRS (Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale) baseline Hindi/English version that was used to assess suicide attempts was developed to address inconsistencies in nomenclature and accurate identification of suicide behavior, as well as to be used in different settings [36]. Previous studies have examined the C-SSRS’s specificity, its sensitivity, and its convergent, divergent, and predictive interpreter validity. It is found to be sensitive to any change, and to be internally consistent (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.937) in various multisite studies [36, 37].

The BIS-11, which was used to assess the spectrum of impulsivity, is a 30-item gold standard measure [38]. It is designed to be a “multifaceted” measure of impulsivity including attentional, motor, and non-planning impulsiveness elucidating its biological, social-interpersonal, and cognitive-emotional dimensions. Its three subscales include cognitive, motor, and non-planning impulsiveness, where Cognitive/Attentional Impulsiveness denotes the tendency to make quick decisions, Motor Impulsiveness denotes acting without thinking, and Non-Planning Impulsiveness indicates lack of forethought. Respondents answer each item on a 4-point scale (“1 = never/rarely”, “2 = sometimes”, “3 = often”, and “4 = almost always/always”), and totals range from 0–120. Several studies, including studies conducted in India, have used the BIS-11 indifferent cultural settings [39] to explore the social significance and behavioral correlates of variability in impulsivity [40]. Published reliability coefficients for the BIS-11 total score (Cronbach’s) range from 0.72 to 0.83 [37].

Aggression assessment was performed with the widely-used, reliable, 25-item Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) [41], which is adapted and modified from the Overt Aggression Scale [42]. It provides a weekly assessment of aggressiveness and was developed to assess four forms of aggressive behavior: verbal aggression, aggression against property, auto-aggression, and physical aggression. Each dimension was measured separately on the basis of behavior in the previous15 days. Respondents were asked in a personal interview to report their behaviors over the past two weeks. Each domain was scored on a 5-point scale and total scores could range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating more aggression. The final score was produced by adding a single multiple of the verbal aggression score, two multiples of the aggression against property score, three multiples of the auto-aggression score, and four multiples of the physical aggression score. It also comprises important forms of aggression, like attempted suicide and intimidation. The psychometric properties of the Modified Overt Aggression Scale have been established by analyzing its inter-rater reliability and predictive power [43].

Statistical analysis included Chi-square and Student’s t test to analyze categorical and continuous variables respectively. The study population was screened for suicide attempt behaviour and the presence of a previous suicide attempt among individuals was considered for case and control classification. More explicitly, this study inspected personality traits, impulsivity and aggression, among Idu Mishmi suicide attempters and compared them to age- and sex-matched non-attempter control individuals. Sex wise interaction between sub-traits of studied variables was examined with the use of Pearson correlation coefficient. Multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were used for association analysis. Bivariate logistic regression was used to examine the joint effect of traits on suicide attempts using different models. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago). The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi. All the participants were informed about the study details and methods in their familiar language before giving their consent.

Results

In the Idu Mishmi population we identified suicide attempters who had made one attempt (n = 31, 17.51%), two attempts (n = 5, 2.82%), and three attempts (n = 3, 1.69%) in their lifetime. Among attempters Hanging (n = 20, 64.52%) and consumption of pesticide (n = 7, 22.58%) were the most preferred modes of both sexes.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the presence or absence of suicide attempts among the Idu Mishmi participants. A high prevalence (22.03%) of suicide attempts is found in the population. There are no significant differences in age, marital status, or education. However, the data show a high frequency of suicide attempts in the groups who are above 19years old, married, and high school educated (studied & currently studying). The study finds significant differences using chi-square statistics between sexes (p = .002*) and occupations (p = .002*), with a high prevalence of female housewives and students in the suicide attempter’s category. However, in all interviewed female and male participants, the prevalence of suicide attempters is found to be 32.89% and 13.86% respectively.

'Table 1

Demographic characteristics of the Idu Mishmi suicide attempters (Univariate chi sqaure (x2)Test analysis).

|

Suicide Attempt | ||||

|

Absent |

Present | |||

|

N = 138 |

77.97% |

N = 39 |

22.03% | |

|

Sex | ||||

|

Male (N = 101) |

87 |

63.00% |

14 |

35.90% |

|

Female (N = 76) |

51 |

37.00% |

25 |

64.10% |

|

x2 |

9.145 |

Sig. |

.002 * | |

|

Age | ||||

|

<19 (N = 37) |

29 |

21.00% |

8 |

20.50% |

|

≥19 (N = 140) |

109 |

79.00% |

31 |

79.50% |

|

x2 |

0.005 |

Sig. |

0.946 | |

|

Marital Status | ||||

|

Married |

78 |

56.50% |

21 |

53.80% |

|

Unmarried/single |

60 |

43.50% |

18 |

46.20% |

|

x2 |

0.088 |

Sig. |

0.766 | |

|

Education | ||||

|

Illiterate |

17 |

12.41% |

5 |

12.82% |

|

Middle |

28 |

20.44% |

11 |

28.21% |

|

high school |

49 |

35.77% |

13 |

33.33% |

|

Intermediate & above |

43 |

31.39% |

10 |

25.64% |

|

x2 |

1.214 |

Sig. |

0.750 | |

|

Occupation | ||||

|

Unemployed |

21 |

15.22% |

6 |

15.38% |

|

Housewife |

15 |

10.87% |

13 |

33.33% |

|

Employed |

64 |

46.38% |

8 |

20.51% |

|

Student |

38 |

27.54% |

12 |

30.77% |

|

x2 |

14.813 |

Sig. |

0.002* | |

- p value<0.05

The mean ± SD of scores on tests for personality traits, like aggression and impulsivity, in each subcategory among suicide attempters and non-attempters, sex wise, are depicted in Table 2. Significant differences are found between all suicide attempters and non-attempters in Total Aggression, and female attempters and non-attempters differ significantly in Auto-aggression. The BIS-11 produced impulsivity score analysis also shows a significant difference between suicide attempters and non-attempters in Total Impulsivity and in subcategories Non-planning and Motor impulsivity. Whereas, in sex-based analysis, only males show significant differences in the subcategoriesmotor and cognitive impulsiveness.

Table 2

Status of aggression and impulsivity among Idu Mishmi suicide attempters in males and females (Univariate t Test analysis).

|

Aggression | |||||||||

|

Male (N = 76) |

Female (N = 58) |

Total (N = 134) | |||||||

|

Present (N = 11) |

Absent (N = 65) |

t Test |

Present (N = 18) |

Absent (N = 40) |

t Test |

Present (N = 29) |

Absent (N = 105) |

t Test | |

|

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD | ||||

|

Verbal aggression |

2.45±1.21 |

2.58±1.48 |

0.318 |

3±1.78 |

2.85±1.72 |

0.300 |

2.79±1.59 |

2.69±1.57 |

0.323 |

|

Aggression against property |

2.36±1.91 |

1.45±1.82 |

1.482 |

1.56±1.53 |

1.25±1.55 |

0.686 |

1.86±1.73 |

1.37±1.72 |

1.356 |

|

Auto-aggression |

1.55±2.54 |

1.06 ±1.71 |

0.608 |

1.28±1.21 |

0.45±0.88 |

2.503* |

1.38±1.82 |

0.83±1.48 |

1.498 |

|

Physical aggression |

3.64±2.66 |

2.69±2.12 |

1.12 |

3.33±1.75 |

2.58±1.82 |

1.507 |

3.45±2.10 |

2.65±2.00 |

1.837 |

|

Total Aggression |

25.18±16.14 |

19.4±13.46 |

1.124 |

23.17±10.04 |

16.92±8.65 |

2.283* |

23.93±12.46 |

18.46±11.87 |

2.116* |

|

Impulsivity | |||||||||

|

Male (N = 79) |

Female (N = 56) |

Total (N = 134) | |||||||

|

Present (N = 10) |

Absent (N = 69) |

t Test |

Present (N = 19) |

Absent (N = 37) |

t Test |

Present (N = 29) |

Absent (N = 105) |

t Test | |

|

Non-Planning |

29.8±3.68 |

27.9±5.15 |

1.443 |

30.42±2.87 |

29.49±3.88 |

1.019 |

30.42±2.87 |

28.72±3.91 |

2.137* |

|

Motor |

26.1±5.15 |

23.23±4.81 |

2.302* |

25.63±4.67 |

24.22±3.80 |

1.141 |

25.63±4.67 |

23.8±3.87 |

2.076* |

|

Cognitive/ Attentional |

20±1.63 |

18.42±3.76 |

2.425* |

19.47±2.61 |

19.57±2.29 |

0.133 |

19.47±2.61 |

19±2.81 |

1.289 |

|

Total Impulsivity |

75.9±7.11 |

69.55±11.14 |

1.746 |

75.53±6.13 |

73.46±6.33 |

1.181 |

75.53±6.13 |

71.59±7.06 |

2.973* |

- p value<0.05

A Pearson’s coefficient of correlation analysis, between all subcategories and total impulsivity and aggression scores, shows high intra-correlation between traits of aggression and impulsivity in both sexes, whereas inter-correlation between categories of aggression and impulsivity is only observed in males (Table 3). In all screened males, non-planning and cognitive impulsiveness is found to be correlated with auto-aggression, motor impulsivity is correlated with physical aggression, and both total aggression and total impulsivity establish a correlation with aggression against property, physical aggression, and total aggression. In sex wise analysis, males show better correlation among the subcategories of aggression, whereas, in females, we record some negative correlation and could not find any significant correlation between the subcategories of impulsivity. The results imply that the traits of impulsivity and aggression are deeply correlated among males.

Table 3

Inter- correlations among traits of aggression and impulsivity in males and females of Idu Mishmi suicide attempters (Univariate Pearson correlation analysis).

|

Categories /Subcategories |

Verbal aggression |

Aggression against property |

Auto aggression |

Physical aggression |

Total Aggression |

Non-Planning |

Motor |

Cognitive/ Attentional |

Total Impulsivity | |

|

MALE | ||||||||||

|

Verbal Aggression |

Pearson Correlation |

0.099 |

0.021 |

.340** |

.393** |

0.059 |

-0.004 |

0.164 |

0.095 | |

|

N |

58 |

58 |

58 |

58 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 | ||

|

Aggression against property |

Pearson Correlation |

.287* |

.272* |

0.111 |

.517** |

0.191 |

-0.126 |

0.058 |

0.047 | |

|

N |

76 |

58 |

58 |

58 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 | ||

|

Auto aggression |

Pearson Correlation |

.233* |

.357** |

0.123 |

.457** |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.071 |

0.082 | |

|

N |

76 |

76 |

58 |

58 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 | ||

|

Physical aggression |

Pearson Correlation |

.274* |

.364** |

.336** |

.832** |

0.15 |

-0.063 |

0.102 |

0.081 | |

|

N |

76 |

76 |

76 |

58 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 | ||

|

Total Aggression |

Pearson Correlation |

.386** |

.675** |

.680** |

.842** |

0.157 |

-0.024 |

0.202 |

0.15 | |

|

N |

76 |

76 |

76 |

76 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 | ||

|

Non-Planning |

Pearson Correlation |

-0.072 |

0.187 |

.267* |

0.193 |

0.232 |

0.092 |

-0.032 |

.566** | |

|

N |

71 |

71 |

71 |

71 |

71 |

56 |

56 |

56 | ||

|

Motor |

Pearson Correlation |

0.028 |

0.227 |

0.073 |

.252* |

.242* |

.401** |

0.205 |

.759** | |

|

N |

71 |

71 |

71 |

71 |

71 |

79 |

56 |

56 | ||

|

Cognitive/ Attentional |

Pearson Correlation |

0.137 |

0.208 |

.240* |

0.127 |

0.23 |

.541** |

.488** |

.517** | |

|

N |

71 |

71 |

71 |

71 |

71 |

79 |

79 |

56 | ||

|

Total Impulsivity |

Pearson Correlation |

0.024 |

.255* |

0.233 |

.243* |

.290* |

.819** |

.797** |

.799** |

|

|

N |

71 |

71 |

71 |

71 |

71 |

79 |

79 |

79 |

||

|

FEMALE | ||||||||||

- . Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

- . Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Table 4 shows an association analysis using Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) between and among personality factors and the outcome of suicide attempts in the Idu Mishmi population. A one-way between-groups multivariate analysis of variance was performed to investigate the relationship between suicide attempts and personality traits. Two dependent variables were used: aggression and impulsiveness. The independent variable was suicide attempt. Preliminary assumption testing was conducted to check for normality, linearity, univariate and multivariate outliers, homogeneity of variance and covariance matrices, and multicollinearity, with no serious violations noted.

Table 4

Association analysis between among personality factors and outcome of suicide attempt multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA analysis).

|

Wilks' Lambda |

F |

Hypothesis df |

Error df |

Sig. |

Partial eta squared | |

|

Cumulative effect |

||||||

|

Aggression Impulsiveness (Combined) |

0.934 |

4.102 |

2.000 |

116.00 |

.019* |

0.66 |

|

Individual Effect |

||||||

|

Aggression |

2.647 |

1 |

117 |

0.106 |

0.22 | |

|

Impulsiveness |

7.274 |

1 |

117 |

.008* |

0.59 | |

- p value <0.05

There was a statistically significant difference between suicide attempters and non-attempters on the combined dependent variables, F (2, 116) = 4.102, p = 0.019; Wilks’ Lambda = 0.934; partial eta squared = 0.66. When the results for dependent variables were considered separately, the only difference reached to statistical significance, using a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of 0.025, was impulsiveness, F (1, 117) = 7.274, p = 0.008, partial eta squared = 0.59. The significant value of impulsiveness implies the profound role of impulsiveness more than aggression, in suicide attempts in the Idu Mishmi population of the Dibang Valley.

Table 5 depicts the results of three separate regression models with potential predictors of suicide attempts. In Model1, aggression, Impulsiveness, gender, and age were analyzed separately in association with suicide attempts and the results establish separate roles of aggression, impulsiveness and gender in suicide attempts. In Model2, when only aggression, Impulsiveness, and suicide attempts were entered simultaneously to control for the impact of gender and age, Impulsiveness remained significant. Whereas in Model 3, demographic variables like gender and age were entered as independent correlates along with aggression and Impulsiveness, and we find a significant role of gender (adjusted Odds Ratio = 3.355 (0.013)* Confidence Interval = 1.289–8.738)and Impulsiveness (adjusted Odds Ratio = 1.079 (0.05)* Confidence Interval = 1.000–1.164)in suicide attempts. Although Impulsiveness remained significantly associated with an increased likelihood of suicide attempts, gender (being female) contributed significantly to the relationship.

Table 5

Association between gender, age, personality factors with suicide attempt among Idu Mishmi (Multivariate logistic regression analysis).

|

Model-1 |

'Model-2'* |

'Model -3'* | |

|

Unadjusted Odds Ratio (Sig.) 95%CI |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (Sig.) 95%CI |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (Sig.) 95%CI | |

|

Aggression |

1.044 (0.017)* 1.008-1.082 |

1.019 (0.348) 0.980-1.060 |

1.026 (0235) 0.983-1.072 |

|

Impulsiveness |

1.091 (0.008)* 1.024-1.164 |

1.087 (0.023)* 1.011-1.167 |

1.079 (0.05)* 1.000-1.164 |

|

Gender 1 = Female |

3.046 (0.003)* 1.453-6.384 |

3.355 (0.013) * 1.289-8738 | |

|

Age 1 = 19 and above |

1.030 (0.946) 0.428-2.482 |

0.838 (0.816) 0.190-3.708 |

Adjusted variables in Model 2 = Impulsiveness, Aggression. Adjusted variables in Model 3 = Gender, age, Impulsiveness, Aggression

- p value <0.05

Discussion

This study reports a high rate of suicide attempts (22.03%) in the Idu Mishmi tribe of the Dibang Valley district of Arunachal Pradesh, India. The issue of suicide in the Idu Mishmi came to light with media reporting of suicide deaths in the Dibang Valley and Lower Dibang Valley, and was later validated by a scientific study in which 218 cases of suicide were reported, over four decades, in this tiny tribe numbering 15,000 [44]. Further, our group has published the presence of high suicide attempt rates and psychiatric traits like depression, anxiety, and eating disorders among Idu Mishmi school children and family members in the lower Dibang district of Arunachal Pradesh [34]. Ethnographic, anthropological, and sociological accounts of indigenous people from India and around the globe have posited the frequent presence of suicide behavior among primitive people [30, 31 45, 46, 47]. Several attempts have been made to unmask the causative and risk factors like psychiatric abnormality, positive family history, alcoholism, depression, having a friend who has attempted suicide, history of physical abuse and sexual abuse, female sex, etc. [48,49]. The stress-diathesis model, which includes the role of childhood trauma and personality traits like impulsivity and aggression, is another attempt to illuminate the complex behavior of suicide [4]. The population aggression score mean recorded in the Idu Mishmi population was 21.20. In a sex wise comparison, the male sex recorded a high mean value. In females, auto-aggression was found to be high. Research indicates that females were less likely to opt for direct physical violence and they can express their aggression though non-physical behaviour. Males, are quicker to show physical aggression and aggression against property. The outcome of this study, the significant differences shown between suicide attempters and non-attempters in the total aggression category, is validated by the shared neurobiology that has been proposed for suicide and aggressive behavior [8]. Aggression has been observed to be concomitant with lowered serotonin-mediated brain activity, and a pattern of emotional dysregulation in the context of interpersonal difficulties and other stressful life events, all of which can result in suicide [10, 50].

The impulsivity trait evaluation among the Idu Mishmi tribal population recorded it to be quite high with a mean of 73.56, compared with other population studies in India [51] which have recorded means of 61.71 in rural and 62.65 in urban samples. Sex wise comparison in the total population shows elevated female impulsivity, with an average 74.5 score, while males mean score was 72.73. However in the suicide attempter category, males’ impulsivity scores were found to be high. Global studies support the higher Impulsiveness scores found in females [40]. However, findings from other indigenous population based studies support the notion of high impulsivity in indigenous people. Doyle et al. (2015) recorded that 42% of non-indigenous inmates and 53% of indigenous inmates screened positive for impulsive personality [52]. A Commission for Children and Young People and Child Guardian Queensland (2009) report noted that suicide impulsivity is frequently reported more among aboriginal youth than the wider Australian youth population [53]. Impulsiveness symptoms have been implicated across neuropsychiatric disorders, with important consequences for everyday activity and quality of life. Studies have explained the variability in impulsive behaviors as stemming from genetic or temperamental roots that interact with psychological and environmental experiences [54, 55, 56,57]. The present population study was an attempt to substantiate earlier findings. Simon et al. (1994) reported that 24% of near-lethal suicide attempt survivors had thought about their suicide attempt for less than 5 minutes [58]. The present study further reports the interplay between categories and subcategories of aggression and impulsivity. Some recent studies have suggested the interplay of aggressive and impulsive behavior to be the underlying link between family history of suicide committers and new suicide attempts [59, 60]. Menon et al., 2015 listed causes of suicide death among Indians and found males’ modes differed from those of females, which could also be explained by the differences in personality characteristics [1].

The outcome of our study suggests that impulsivity and gender (being female) may contribute significantly as risk factors for suicide attempts with variability in the category and subcategories of aggression and impulsivity across sexes. Kumar et al. 2013 also observed a difference between male and female suicide attempters with respect to concurrent diagnoses, mode of attempt, and stressful life situations encountered [2]. To summarize, it can be stated that in the stress-diathesis model, aggression and impulsivity are important components of the diathesis for suicidal behavior. Inference from this study suggests that suicide behaviour needs multidisciplinary understanding and it should involve knowledge from psychologists, anthropologists, and ethnographers. The magnitude of socio-cultural factors in the cultural personality background should be studied so that a sound suicide prevention program can be planned.

Conclusion

The present study among the Idu Mishmi, an isolated endogamous tribal group, focuses on the presence of a high suicide attempt rate and sex variability. High scores on measures of aggression and impulsivity traits were recorded, with significant differences among suicide attempters and non-attempters. Male attempters were more at risk of impulsivity, whereas females showed greater risk for aggression, but in the total studied population, the suicide risk was almost three times higher with higher aggression, and almost twice as high with higher impulsivity. The subcategories of impulsivity were deeply correlated among themselves and with subcategories of aggression. Most of the previous studies emphasized considering suicide attempts to be the best diagnostic trait of suicidal behavior [61] and that it should possess the qualities of being self-initiated, potentially injurious behavior with the presence of intent to die and nonfatal outcome [62]. This study validates a suspicion raised by earlier scholars, as the high intensity of aggression and impulsivity in indigenous populations and their association with suicide behavior was re-witnessed in the present population-specific study.

Limitations

The limitation of small sample size is due to the small population size, low density, and difficult terrain of their habitation. We could not observe the interplay of psychiatric abnormalities and the traits of aggression or impulsivity due to the absence of a psychiatric clinic in the study area. Further, deaths due to suicide could not be quantified in the absence of postmortem based data.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the role of the District Commissioner and Medical Officer, Dibang Valley District, Arunachal Pradesh, India for their support during field work in hilly, tough terrain. We deeply convey our thanks to our fieldguides, nata, naya (elder members of the Society) and study participants.

Funding Statement

We are thankful to University of Delhi for financial assistance (R & D Grant for the year 2013) to VR and ICMR Research Fellowship (Ref 3/1/3/17 (HRD) DT 3rd September 2010) to PKS. Fund were provided only for performing field and collecting data.

See also

Arunachal Pradesh: Demographics/ Religion

Idu Mishmi

Scheduled Tribes: All-India list