Lakhimpur District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Lakhimpur District

Physical aspects

District in Eastern Bengal and Assam, occupying the extreme eastern portion of the Brahmaputra Valley. The actual boundaries have never been definitely determined ; but an inner line has been laid down, which serves as the limit of ordinary British jurisdiction, without prejudice to claims to the territory on the farther side. The tract of land thus defined lies between 26° 49' and 27° 52' N. and 93" 46' and 96° 5' E., with an area of 4,529 square miles. In its broader sense, the District is bounded on the west by Darrang and Sibsagar ; on the north by the Dafla, Rliri, Abor, and Mishmi Hills ; on the east by the Mishmi and Khamti Hills ; and on the south by the hills inhabited by independent tribes of Nagas.

The portion of the District included within the inner line consists of a broad plaui surrounded on three asnects sides by hills, and divided by the channel of the Brahmaputra. Near the river lie extensive marshes covered with reeds and elephant-grass, but as the level rises these swamps give place to rice-fields and villages buried in thick groves of fruit trees and bamboos. South of the Brahmaputra a great portion of the plain is covered with trim tea gardens, many of which have been carved out of the dense forest, which still lies in a belt many miles broad along the foot of the hills ; but on the north bank the area under tea is comparatively small, and there are wide stretches of grass and tree jungle.

The aspect of the plain is thus pleasingly diversified with forest, marsh, and river ; and the hills themselves, with their snow-capped summits, afford a striking background to the scene on a clear day in winter. The Brahmaputra runs through the District, receiving on the north bank the DiBANG, the Dihang, and the Suban.siri. Even in the dry season large steamers can proceed to within a few miles of Dibrugarh, and during the rains boats of considerable burden can go as far as Sadiya. Beyond that place the river is still navigable for light native craft almost to the Brahmakund. The principal tributaries on the south bank are the Noa Diking, the Dibru, and the Burhi Diking. There are no lakes of any importance, but there are numerous bits and marshes, of which the largest are at Bangalmari and Pabhamari on the north bank of the Brahmaputra.

The plain is of alluvial origin, consisting of a mixture of clay and sand in varying proportions. The hills which surround it on three sides belong to the Tertiary period, and are composed of sandstones and shales.

Low-lying ground is covered with high grass and reeds, the three principal varieties being ikra {Saccharum arundinacetim), nal {Phrag- mites Roxbiirghii), and khagari {^Saccharum spontaneiim). The central portion of the plain is largely under cultivation, but near the hills the country is covered with dense evergreen forest.

Wild animals are common, including elephants, rhinoceros, buffaloes, bison, tigers, leopards, bears, and deer. A curious species of wild goat or antelope called iakiti {Budorcas taxicolor) is found in the Mishmi Hills, but no European has yet succeeded in shooting a speci- men. In 1904 wild animals killed 1,559 cattle, and rewards were paid for the destruction of 58 tigers and leopards ; 39 elephants were also captured in that year. Small game include florican, partridges jungle-fowl, geese, duck, and snipe.

The climate is particularly cool and pleasant, and only during the three months of June, July, and August is inconvenience experienced from the heat. In December and January fogs are not uncommon, and fires are often needed at night even in the month of March. The District, as a whole, is healthy, except in places where the forest has been recently cleared.

The hills with which Lakhimpur is surrounded on three sides, and the vast expanses of evergreen forest, tend to produce a very heavy rainfall. At Pathalipam, under the Miri Hills, the annual rainfall averages 168 inches, but towards the south it sinks to 100 inches, and in places to a little less. The great earthquake of June 12, 1897, did very little damage, and the District does not suffer much from either storm or flood.

History

The earliest rulers of Lakhimpur of whom tradition makes any mention seem to have been Hindus of the Pal line, whose capital was situated in the neighbourhood of Sadiya. About the eleventh century they were overthrown by the Chutiyas, a tribe of Tibeto-Burman origin, who entered Assam from the north-east and established themselves on the upper waters of the Brahmaputra.

In 1523 the Chutiyas themselves, after some centuries of conflict, were finally crushed by the Ahoms, a Shan tribe who had descended from the Patkai into Sibsagar District nearly 300 years before ; and Lakhimpur, with the rest of Assam proper, formed part of the territories of the Ahom Raja. Towards the close of the eighteenth century, when the Ahom kingdom was tottering to its fall, the high-priest of the Moamarias, a Vaishnavite sect, rose in rebellion against the reigning king. For a time, the rebels met with a measure of success \ but when the royal arms were again in the ascendant, the Ahom prime minister revenged himself by desolating the whole of Lakhimpur lying south of the Brahmaputra. A few years later the Burmans entered the valley, at the invitation of one of the claimants to the Ahom throne, and were guilty of gross atrocities before they were finally expelled by the British in 1825.

The District was by this time almost depopulated and was reduced to the lowest depths of misery. During the confusion attendant on the break-up of the Ahom kingdom, the head of the Moamaria sect established himself in a position of quasi-independence in the Matak territory, a tract of land lying between the Brahmaputra and the Buri Dihing, and bounded on the east by an imaginary line drawn due south from Sadiya. On the occupation of the country by the British this chief, who bore the title of Bor Senapati, was confirmed in his fief on the understanding that he provided 300 men for the service c)f the state. The arrangement was, however, found t(j Ix; unsatisfactory ; and, in lieu of any claim on the services of his subjects, Government accepted a revenue of Rs. 1,800. In 1842, after the death of the Bor Senapati, the whole of the Matak territory was annexed.

Matak was not the only fief carved out of the decaying Ahom empire. In 1794 the Khamtis crossed the Brahmaputra, and ousted the Assamese governor of Sadiya. The Ahom king was compelled to acquiesce in this usurpation, and the Khamti chief was accepted as a feudatory ruler of Sadiya by the British Government. In 1835 it was found necessary to remove him for contumaciously seizing some territory claimed by the Matak chief, in defiance of the orders of the British officer, and the country was brought under direct administration. Four years later the Khamtis rose, surprised Sadiya, killed the Political Agent, Colonel White, and burned the station.

The rising was, how- ever, put down without difficulty, and the tribe has given no trouble since that date. In 1833 the North Lakhimpur subdivision was handed over to the Ahom Raja, Purandar Singh, as it was at that time proposed to establish him as a feudatory prince in the two upper Districts of the Assam Valley. Five years later this territory was again resumed, as the Raja was found unequal to the duties entrusted to him. The history of the District since it has been placed under British administration is a story of continuous development and increasing prosperity. From time to time the tribes inhabiting the Abor and Mishmi Hills have violated the frontier, but their raids have had no material effect upon the general welfare of the people. There are few remains of archaeological interest in Lakhimpur, but the ruins found near Sadiya show that this portion of Assam must once have been under the control of princes of some power and civilization.

Population

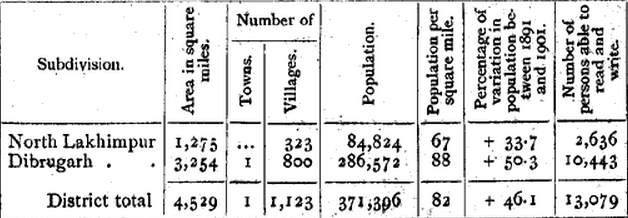

The population of the District at the last four enumerations was : (1872) 121,267, (1881) 179,893, (1891) 254,053, and (1901) 371,396. Within twenty-nine years the population has more than trebled, this enormous increase being partly due to the fact that Lakhimpur, unlike Lower and Central Assam, has been healthy, so that the indigenous inhabitants increased in numbers, but still more to the importation of thousands of coolies required for the tea gardens and other industries of the District. Lakhimpur is divided into the two subdivisions of Dibrugarh and North Lakhimpur, with head-quarters at the places of the same name. It contains one town, Dibrugarh (population, 11,227), the District head-quarters ; and 1,123 villages.

The following table gives statistics of area, towns and villages, and population according to the Census of 1901 : —

About 90 per cent, of the population in 1901 were Hindu.s, 3 per cent. Muhammadans, and 5 per cent, members of animistic tribes. The proportion of foreigners is very high, and 41 per cent, of the people enumerated in Lakhimpur in 1901 had been born outside the Province. A large number of these immigrants have left the tea gardens, and settled down to ordinary cultivation in the villages. Assamese was spoken by only 39 per cent, of the population, while 21 per cent, returned Bengali, and 20 per cent. Hindi or Mundarl, as their usual form of speech.

The principal Assamese castes are the Ahoms (59,100), the Chutiyas (17,500), the Kacharis (25,200) and the Miris (24,900). The chief foreign castes are Mundas (30,200), Santals (17,500), and the Bhumij, Bhuiya, and Oraon. The higher Hindu castes are very poorly represented. Members of European and allied races numbered 469 in 1 90 1. In spite of the existence of coal-mines, oil-mills, railways, and a prosperous trading community, 87 per cent, of the people are dependent upon the land for their support.

A clergyman of the Additional Clergy Society is stationed at Dibrugarh, and there are two missionaries in the District. The total number of native Christians in 1901 was 2,606.

Agriculture

The soil varies from pure sand to a stiff clay, which combine in varying proportions to form a loam. The high land is admirably adapted for the growth of tea ; and the abundance of the rainfall, the immunity from flood, the large proportion of new and unexhausted land, and the opportunities for selection afforded by the sparseness of the population, combine to render agriculture a more than usually lucrative occupation.

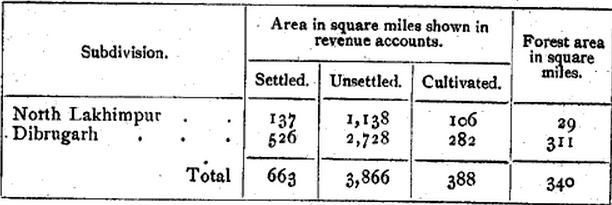

The table on the next page shows what a large proportion of the District is still lying waste.

Rice is the staple crop, and in 1903—4 covered 231 square miles, or 57 per cent, of the total cropped area. More than four-fifths of the rice crop is usually sdli or transplanted winter rice, and the greater part of the remainder is dhu, or summer rice grown in the marshy tracts before the floods rise. Tea is the only other crop of any importance; but minor staples include pulse (6,100 acres), mustard (8,000 acres), and sugar-cane (3,500 acres). No agricultural statistics are prepared for the land occupied by hill tribes, who pay a poll tax irrespective of the area cultivated. The usual garden crops are grown, including plantains, vegetables, tobacco, pan or betel-leaf, and areca- nut. The last two were introduced into Lakh im pur after the country had been occupied by the British.

Lakhimpur was the scene of the first attempts at tea cultivation by Government in 1835, and the Assam Company commenced operations here in 1840. The industry has passed through many vicissitudes, which were chiefly due to speculation, but the abundant rainfall and fertile .soil have always given a large measure of pro.sperity to the gardens of Upper Assam. Of recent years there has been a great expansion of the industry. In 1880, 19,700 acres were under cultiva- tion. By 1896 the area had risen to 48,200 acres, and in the next five years there was a further increase of 20,000 acres. In 1904 there were altogether 143 gardens with 70,591 acres under plant, which yielded more than 30,000,000 lb. of manufactured tea and gave employ- ment to 199 Europeans and 100,849 natives, the latter of whom had been recruited from other parts of India. The principal companies are the Dum Duma Company, with head-quarters at Dum Duma ; the Jokai Company, with head-quarters at Panitola ; the Assam Frontier Tea Company, with head-quarters at Talap ; and the Dihing Company, with head-quarters at Khowang.

Apart from tea, the District has witnessed a rapid increase of cultivation, and between 1891 and 1901 the area settled at full rates, excluding land held by planters, increased by 56 per cent. Little attempt has, however, been made to introduce new crops or to improve upon old methods. The harvests are regular, the cultivators fairly well-to-do, and agricultural loans are hardly ever made by Government. The heavy rainfall renders it unnecessary to have re- course to artificial irrigation.

The native cattle are of very poor quality, with the exception of buffaloes, which are fine animals. The inferior character of the live- stock is chiefly due to neglect, and to disregard of the most elementary rules of breeding, as there is still abundance of waste land suitable for grazing, and in few places is any difficulty experienced in obtaining pasture.

Forests

The ' reserved ' forests of Lakhimpur covered an area of 340 square miles in 1903-4. The largest Reserves are the Upper Dihing near „ Margherita, and the Dibru near Rangagora on the Dibru river. The wants of the District are, however, fully supplied from the Government waste lands, which cover an area of 3,062 square miles ; and as there is no external trade in timber, the out-turn from the Reserves has hitherto been insignificant. The most valuable timber trees are nahor {Mesua ferrea\ ajhar {Lagerstroemia Flos Reginae\ makai {Shorea assamica), and bola {Morus laevigata) ; but the largest trade is done in sinml {Botnbax malabariait)i), a soft wood much in request for tea boxes. The duty levied on rubber, whether collected within or beyond the frontier, is a valuable source of revenue, the receipts under this head having averaged nearly a quarter of a lakh during the decade ending 1901. A considerable sum is also paid for the right to cut cane in Government forests.

Minerals

The hills to the south contain two important coal-fields, those of Makum and Jaipur. The Makum field is extensively worked near Margherita, the out-turn in 1903 amounting to 239,000 tons, on which a royalty of Rs. 36,000 was paid to Government. Petroleum oil is found in the same strata, and a large refinery has been constructed near the wells at Digboi. The Government revenue from oil in 1903-4 was Rs. 3,750. The coal measures also contain salt springs, and ironstone and iron ore in the form of impure limonite, from which iron used to be extracted in the days of native rule. Boulders of liniestone are found in the bed of the Brahmaputra near Sadiya, and there is a thick deposit of kaolin near the Brahmakund. Under the Ahom Rajas the gold-washing industry was carried on in most of the rivers ; but this gold is probably doubly derivative, and is washed out of the Tertiary sandstones of the sub-Himalayan formations, which are themselves the result of the denudation of the rocks in the interior of the chain. A considerable sum of money was expended in 1894 on the exploration of the Lakhimpur rivers, but gold was not found anywhere in paying quantities, and no return was obtained on the capital invested.

Trade and Communication

Apart from tea, oil, and saw-mills, and the pottery and workshops of the Assam Railways and Trading Company, local manufactures are of little importance. The Assamese weave cotton and silk cloth, but more for home use than for sale. Brass vessels are produced m small quantities by the Morias, a class of degraded Muhammadans, but the supply is not equal to the demand. Jewellery is made, but only as a rule to order, by the Brittial Baniyas. The raw molasses produced from sugar-cane is of an excellent quality, and finds a ready sale, but the trade has not yet assumed any considerable dimensions. There is a large oil refinery at DiGBOi, and brick and pottery works have been opened at Ledo near Margherita. In 1904 there were four saw-mills in the District, employing 743 hands. The largest mills were situated at Sisi, and the greater part of the out-turn consists of tea boxes.

Till recently, the Brahmaputra was the sole channel of external trade, but the completion of the Assam-Bengal Railway has provided through land communication with Chittagong and Gauhati. The bulk of the external trade of the District is carried on with Calcutta. The chief exports are tea, coal, kerosene and other oils, wax and candles, hides, canes, and rubber. The imports include rice, gram, and other kinds of grain, ghi^ sugar, tobacco, salt, piece-goods, mustard and other oils, corrugated iron, machinery, and hardware. The trade of the District is almost entirely in the hands of the Kayahs, as the Marwari merchants are called ; but in the larger centres a few shops for the sale of furniture and haberdashery are kept by Muhammadans from Bengal. These centres are Dibrugarh, the head-quarters town, Sadiva, Dum Duma, Margherita, Jaipur, Khowang, and North Lakhimpur ; but the Kayahs' shops are scattered all over the District, and numerous weekly markets are held, at which the cultivators can dispose of their surplus products and the coolies satisfy their wants. Most of the frontier trade is transacted at Sadiya and North Lakhimpur, and is chiefly carried on by barter. The principal imports are rubber, ivory, wax, and musk.

A daily service of passenger steamers and a fine fleet of cargo boats, owned and managed by the India General Steam Navigation Company and the Rivers Steam Navigation Company, ply on the Brahmaputra between Goalundo and Dibrugarh. Feeder steamers also go up the Subansiri to Bordeobam. South of the Brahmaputra, Lakhimpur is well supplied with means of communication. A metre- gauge railway runs from Dibrugarh ghat to the Ledo coal-mines, a distance of 62 miles, with a branch 16 miles long from Makum junction to Talap. This line taps nearly all the important tea gardens, and at Tinsukia meets the Assam-Bengal Railway, and thus connects Dibru- garh with Gauhati, and with the sea at Chittagong. In addition to the railway, there were in the District, in 1903-4, 20 miles of metalled and 211 miles of unmetalled road maintained by the Public Works department, and 6 miles of metalled and 516 miles of unmetalled roads kept up by the local boards. The most important thoroughfares are the trunk road, which runs from the Dihing river to Sadiya, a distance of 86 miles, and the road from Dibrugarh to Jaipur. On the north bank of the Brahmaputra population is comparatively sparse, the rainfall is very heavy, and travelling during the rains is difficult. Most of the minor streams are bridged, but ferries still ply on the large rivers.

Famine

Famine or scarcity has not been known in Lakhimpur since it came under British rule, but prices usually range high, as the District does not produce enough grain to feed the large immigrant population.

Administration

There are two subdivisions : Dibrugarh, which is under the im- mediate charge of the Deputy-Commissioner ; and North Lakhimpur, which is usually entrusted to a European Magistrate.

The ordinary District staff includes three Assistant Magistrates, one of whom is stationed at North Lakhimpur, and a forest officer. The Sadiya frontier tract in the north-east corner is in charge of an Assistant Political officer. The Criminal Procedure Code is not in force in this tract, which is excluded from the jurisdiction of the High Court, and the Deputy-Commissioner exercises powers of life and death, subject to confirmation by the Chief Commissioner.

The Deputy-Commissioner has the powers of a Sub-Judge, and the Assistant Magistrates exercise jurisdiction as Munsifs. Appeals, both civil and criminal, lie to the Judge of the Assam Valley, but the chief appellate authority is the High Court at Calcutta. The people are as a whole law-abiding, and there is little serious crime. Special rules are in force for the administration of justice in the Sadiya frontier tract.

The land revenue system resembles that in force in the rest of Assam proper. The settlement is ryohvari, being made direct with the actual cultivators of the soil, and is liable to periodical revision. The District contains large tracts of waste land, and the settled area of 1903-4 was only 15 per cent, of the total, including rivers, swamps, and hills. Villagers are allowed to resign their holdings and take up new plots of land on giving notice to the revenue authorities, and in 1903-4 nearly 14,000 acres of land were so resigned and 25,000 acres of new land taken- up. Fresh leases are issued every year for this shifting cultivation, and a large staff of mandals is maintained to measure new land, test applications for relinquishment, and keep the record up to date. Like the rest of Assam proper, the District was last resettled in 1893. The average assessment per settled acre assessed at full rates in 1903-4 was fixed at Rs. 2-7-4 (maximum Rs. 4-2, minimum Rs. i-ii).

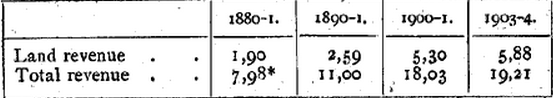

The table below shows the revenue from land and total revenue, in thousands of rupees : —

Outside the municipality of Dibrugarh, the local affairs of each subdivision are managed by a board presided over by the Deputy- Commissioner or the Subdivisional Officer. The European non-official members of these boards, elected by the planting community, give valuable aid to the administration. The total expenditure in 1903-4 amounted to Rs. 1,31,000, more than half of which was laid out on public works. Less than one-third of the income is derived from local rates, which are supplemented by a large grant from Provincial revenues. The District is in a comparatively advanced state of development, but the population is so scanty that it is impossible to provide entirely for local requirements out of local taxation.

For the purposes of the prevention and detection of crime, the Dis- trict is divided into ten investigating centres, and the civil police force consisted in 1904 of 29 officers and 154 men. There are no rural police, their duties being discharged by the village headmen. The military police battalion stationed in the District has a sanctioned strength of 91 officers and 756 men; but it supplies detachments for duty in Darrang and Sibsagar, besides holding sixteen outposts in Lakhimpur. In addition to the District jail at Dibrugarh, a subsidiary jail is maintained at North Lakhimpur, with accommodation for 30 males and 3 females.

As far as literacy is concerned, Lakhimpur is a little in advance of most of the Districts of the Assam Valley. The number of children at school in 18S0-1, 1 890-1, 1 900-1, and 1903-4 was 2,271, 2,998, 5,501, and 5,219 respectively. The number of pupils in 1903-4 was nearly treble the number twenty-nine years before, but the proportion they bore to the total population was less than in the earlier year. This result is, however, largely due to the influx of illiterate coolies, and there can be little doubt that education has spread among the indigenous inhabitants. At the Census of 190 1, 3-5 per cent, of the population (6-2 males and 0-5 females) were returned as able to read and write. There were 166 primary, 9 secondary, and 2 special schools in the District in 1903-4. The number of female scholars was 143. A large majority of the pupils under instruction were only in primary classes, and the number of girls attending secondary schools was extremely small. Of the male population of school-going age 13 per cent, were in the primary stage of instruction, and of the female population of the same age less than one per cent. The total expendi- ture on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 80,000, of which Rs. 13,000 was derived from fees. About 22 per cent, of the direct expenditure was devoted to primary schools.

The District possesses 2 hospitals and 6 dispensaries, with accom- modation for 107 in-patients. In 1904 the number of cases treated was 72,000, of whom 1,200 were in-patients, and i,ioo operations were performed. The expenditure in the same year was Rs. 16,000, the greater part of which was met from Local and municipal funds.

In 1903-4, 39 per 1,000 of the population were successfully vac- cinated, which was rather below the proportion for Assam as a whole. Vaccination is compulsory only in Uibrugarh town.

[Sir W. W. Hunter, A Statistical Accomit of Assam, vol. i (1879) ;

A. Mackenzie, History of the Relations of the Govenitnefit with the Hill Tribes of the North-East Frontier of Bengal (Calcutta, 1884);

B. C. Allen, District Gazetteer of lakhimpur (1905).]