Kota: coaching institutes

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Prohibitory orders since 1989

The Times of India, Sep 13, 2016

Since 1990s, over one lakh residents of parts of Kota city have been living under the shadow of prohibitory orders under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code or CrPC, which has prevented them from hosting any public functions and processions, except during marriages and funerals.

Places like Bajaj Khana, Ghanta Ghar, Makbara Patan Pole and Tipta, stretching over an area of two kilometre in Kota city where a large section of residents belong to the minority community, had been placed under prohibitory orders which prohibits the assembly of four or more persons after outbreak of communal violence in 1989.

But residents claim that the restrictions have been continuing till day though no law and order problem has been reported and it was a "stigma" for them. Locals allege that banks refuse to grant them loans and officials ignore their grievances. Section 144 was imposed following the lifting of curfew after communal riots took place in September 1989. However, the then district collector of Kota (S N Thanwi) in September 1990 issued a circular extending the imposition of the Section "till the next order", which never came.

"The locals in the area are forced to lead an inferior life as they have not been to carry any cultural, social religious programmes or procession for last 27 years," state secretary of Centre of Indian Trade Unions R K Swami said.

"We are facing apathy of the administration due to the current situation," said Sarfaraj Ansari, a local resident who was only 22 years old when the order was imposed. The locals moved court in March 2009 against the long imposition of the CrPC section in the area, Swami said.

He said though the state government gave a positive reply to the court, the restrictions were not lifted in the area where a sizeable population belongs to the minority section. There has been no major crime or unlawful activity in the these areas for the last several years but the locals still have to face the changing dates in the court instead of an order lifting the imposed section, Ansari added. Asked about the issue, District Collector Ravi Kumar Surpur evaded a direct reply and said that the section is invoked to ensure there is no breach of peace.

"Section 144 is a preventive and precautionary measure to maintain law and order situation. That is the very reason that certain practices are followed that there should not be breach of peace, should not be disturbance in the communal harmony," he said An RTI activist said that not lifting the restrictions for such a long duration is a "violation of civil rights."

Media have always divisive agenda. Only minority and Dalit news are highlighted to break the country.

"Imposition of Section 144 in civil area of the city for as long as 27 years is clearly violation of civil rights and is not in favour of the country and the democracy," said Phralad Singh Chadda, RTI activist in Kota. Section 144 can be imposed for a maximum of six months, advocate Jamil Ahamed said.

The coaching institutes of Kota

The Times of India, June 8, 2016

Anindo Dey & Shoeb Khan

The stress chambers of Kota coaching

In 2015, 17 students committed suicide. Anti-depressants sell like hot cakes. Students are struggling to cope with growing stress levels. The police, however, are not perturbed. Since 2010, 69 students enrolled with the 130-odd engineering or medical coaching institutes in the city have taken their own lives, says Kota SP Sawai Singh Godara. Almost 70% of these deaths were a result of the student being unable to cope with the pressure of studies, he says. The remaining ended their life over disappointment in their love life or over family issues. “You can't say there is a surge in cases of suicide among students. If the annual number of 14 or 16 cases of suicide go up to 20 or 24, that will be a surge,“ says Godara, adding that the `suicide rate' is within `global norms'.

NO SCREENING TESTS

There is alarm in the city .District collector R K Surpur in March 2016 directed the institutes to re-start screening tests that can provide students and parents with a fair assessment of the child's aptitude.Screening tests were prevalent till 2005-06, but disappeared as coaching centres set up shop and competition turned stiff. The result: even students with scores less than 50% in Class XII are also being enrolled.

The state may be mulling ways to make the screening test mandatory, but coaching institutes insist they will introduce entrance tests if the same rule applies to coaching institutes in Hyderabad, Chennai, Bangalore, Pune and Delhi.

TOUGH FOR THE MIDDLING STUDENTS

Students like these two girls make up a sizeable section of students stuck in Kota: living out their parents' dreams. Parents willing to sink big money in the pursuit: over Rs 6 lakh in some cases for a two-year stint at being coached to appear for a qualifying exam to a medical or engineering college.

Hostels range from the dingy, dimly lit room at Rs 1,000 per month to those that serve food of choice, a snooker table and two holiday packages per year, all at Rs 25,000 per month.

It's a far cry from the Kota of the 1980s. After the collapse of J K Synthetics, the coaching institutes became a lifeline for the struggling city . But with the success of the pioneers, the town attracted a host of players, even foreign ones, promising students' victory in killer competitions.

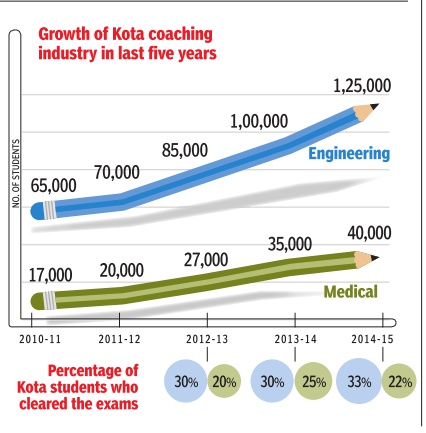

As coaching centres mushroomed in the last 10 years, and coaching became an `industry', many of the lesser known tutorials took on students without any qualifying test, irrespective of a child's current school standing.For the 60,000 children, between ages 14 and 18 who end up in the city every year, there is admission for all irrespective of marks, in many of the institutes.

KIDS ON ANTI-DEPRESSANTS

The stakes are high, students burdened with the need to fare well, and bring their parents “return on investment“. It explains why former member of the district child welfare committee Vimal Jain is a disturbed man. His medicine shop has seen a rapid increase in students buying antidepressants on prescriptions from psychiatrists. He says, “How can those getting 50% compete with the 90-percenters?“ Following reports of suicide, Surpur instructed the institutes to institutionalise systems to deal with depression and related issues among their students. “These kids may never have ventured out of their house but here they have to interact with everyone -from the shopkeeper to the washerman. Even the food they eat may not be their natural diet. It is how they break; simply being unable to cope,“ he says.

The direct feed to parents of scores on their cell phones is a nightmare. Further, institutes segregate weaker students from the better-performers; teachers tasked to spend more time grooming the better ones so that an institute's scores a higher `success rate'. If that pushes a child over the edge, to the point of killing himself herself, it's just another tragedy .

Why Kota is so killing

The Times of India Jan 03 2016

Akhilesh Singh

18-hour study schedules A brutal sorting system that segregates `average' students No fee refund policies for those who want out `We can't take it anymore.

Our parents have told us to return home only after cracking IIT-JEE,“ said two distressed young students to psychologist Dr ML Agarwal in Jawaharnagar, Kota. The boys were both from Bhatinda, Punjab, where they lived in large joint families.They found themselves unable to cope in their new environment, with daily tutorial classes, and having to study for up to 18 hours a day . “It took months of therapy at a rehabilitation centre, and the involvement of their families, to restore them,“ says Dr Agarwal.

These breakdowns are all too common, across a city that reinvented itself in the late '90s as coaching hub for the hyper-competitive engineering and medical school exams. Roughly 1.6 lakh teenagers from the surrounding states flock to Kota's coaching institutes every year, paying between 50,000 and a lakh for annual tuition. Some begin early , as coaching centres also run ghost schools where they enroll middle-school students. In a few institutes, they are taught by IIT alumni, who claim salaries of Rs 1.5-2 crore for their expertise. Neither coaching centres nor hostels have exit policies or refunds, so for students who borrow money to come to Kota, the stakes are even higher.

Most students live in rented rooms with minimal facilities. They may desperately dream of IIT, but many of them are unprepared for the psychological costs. Kota has now become a byword for student suicides. A 14-year-old boy killed himself recently , the 30th suicide last year. Purushottam Singh, whose nephew Shivdutt committed suicide on December 22, is in tears as he talks of the boy . Back home in Kollari village, Dholpur, Singh says, “there were high expectations of him. His family and neighbours had already started calling him doctor sahib.“

The parents of 17-year-old Suresh Mishra (name changed), from Vidisha, now regret having sent him to Kota. “It started with headache, fatigue and bed-wetting. He now suffers from blackouts, partial memory loss and occasional hallucinations,“ says his father Mukund.

Around the world, student burnout is caused by high rates of physical and emotional exhaustion, a sense of being depersonalised, and a shrunken sense of personal achievement. Kota is a cauldron for all these feelings, with other factors like the fear of letting down one's family , or not having any career alternatives.

All around Kota, the message is to excel, or be left behind. Billboards celebrate success and star students. Entry into IITs or the other engineering and medical schools is seen as the only measure of worth. Coaching institutes, though, admit anyone who can pay the fee. Then begins the brutal sorting of students into different batch es on the basis of their performance. Those who lag in their studies live in terror of these internal assessments, and struggle with their sense of inadequacy . Some are doubly challenged, with the Class XII board and the competitive exams.

The problem, though, is that while Kota's coaching centres can find and hone smart stu dents into the perfect JEE test-takers, they are thrown by “weakness“ in students. Their performance criteria does not factor in vulnerability or burnout at all, making it hard for students to seek help.As Naveen Maheshwari, the director of Kota's largest coaching institute puts it, “average performers are bound to fail“ in this competitive place. “In such an environment, parents should understand that IITs and AIIMS are not the end of the world. They should stop imposing their own dreams on children.“

And yet, the idea that coaching centres have a responsibility for the mental wellbeing of stu dents in their tutelage is only now dawning on them. Maheshwari now plans to institute ran dom silent psychometric tests to detect vulner able students who can be kept under watch.

However, he claims that students get even more depressed if their parents take them back home.

Meanwhile, jolted by the serial suicides, the district administration is also awakening to its responsibility. Kota collector Ravi Kumar, says, “We have taken some steps, like an advisory to coaching institutes to screen students for apti tude. We are setting up a helpline to counsel students.“

Bihar Tiger Force

The Times of India, Jun 08 2016

On May 13, 2016, in one of the most violent incidents in the history of Kota involving students, a group of nearly 50 coaching students, part of a group called the Bihar Tiger Force, stabbed to death a 19-year-old student Satya Prakash `Prince' and another student on May 13. It brought to the fore the other strand of the Kota story . About 1.50 lakh to 2 lakh students in the age group of 14 to 19 years are enrolled in various coaching institutes in Kota.Around 60,000 make their way to the city every year, about 25,000 from Bihar alone.

The Bihar Tiger Force are the self-styled `helpdesk' for these newcomers.

They receive students at the station, and help them with accommodation and recommending coaching institutes as well. All for a fee of Rs 500. A typical hostel here is an apartment building whose owner rents out the flats. Members of the Bihar Tiger Force are often the mediators. If an owner rents out the apartment building for say , Rs 60,000 per month, to the BTF, the group rents out the apartments to the newbie students, making a healthy cut on the deals.

The BTF is not the only such group, but is the most powerful in the city . At its helm are not students preparing for any test, but those who have been unsuccessful in repeated attempts --well past age 19: the upper limit for appearing in the IIT entrance test. They have stayed on in Kota, making a `livelihood'.

Following Satya Prakash's murder, the police have arrested two members of the BTF.Hostels have been alerted to tell police about all above-19 residents on their premises.