Kota: coaching institutes

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Prohibitory orders since 1989

The Times of India, Sep 13, 2016

Since 1990s, over one lakh residents of parts of Kota city have been living under the shadow of prohibitory orders under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code or CrPC, which has prevented them from hosting any public functions and processions, except during marriages and funerals.

Places like Bajaj Khana, Ghanta Ghar, Makbara Patan Pole and Tipta, stretching over an area of two kilometre in Kota city where a large section of residents belong to the minority community, had been placed under prohibitory orders which prohibits the assembly of four or more persons after outbreak of communal violence in 1989.

But residents claim that the restrictions have been continuing till day though no law and order problem has been reported and it was a "stigma" for them. Locals allege that banks refuse to grant them loans and officials ignore their grievances. Section 144 was imposed following the lifting of curfew after communal riots took place in September 1989. However, the then district collector of Kota (S N Thanwi) in September 1990 issued a circular extending the imposition of the Section "till the next order", which never came.

"The locals in the area are forced to lead an inferior life as they have not been to carry any cultural, social religious programmes or procession for last 27 years," state secretary of Centre of Indian Trade Unions R K Swami said.

"We are facing apathy of the administration due to the current situation," said Sarfaraj Ansari, a local resident who was only 22 years old when the order was imposed. The locals moved court in March 2009 against the long imposition of the CrPC section in the area, Swami said.

He said though the state government gave a positive reply to the court, the restrictions were not lifted in the area where a sizeable population belongs to the minority section. There has been no major crime or unlawful activity in the these areas for the last several years but the locals still have to face the changing dates in the court instead of an order lifting the imposed section, Ansari added. Asked about the issue, District Collector Ravi Kumar Surpur evaded a direct reply and said that the section is invoked to ensure there is no breach of peace.

"Section 144 is a preventive and precautionary measure to maintain law and order situation. That is the very reason that certain practices are followed that there should not be breach of peace, should not be disturbance in the communal harmony," he said An RTI activist said that not lifting the restrictions for such a long duration is a "violation of civil rights."

Media have always divisive agenda. Only minority and Dalit news are highlighted to break the country.

"Imposition of Section 144 in civil area of the city for as long as 27 years is clearly violation of civil rights and is not in favour of the country and the democracy," said Phralad Singh Chadda, RTI activist in Kota. Section 144 can be imposed for a maximum of six months, advocate Jamil Ahamed said.

The coaching economy

As in 2021

From: Shoeb Khan, January 16, 2021: The Times of India

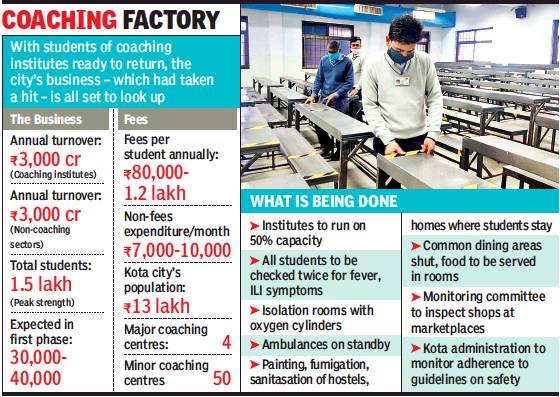

See graphic:

The coaching economy of Kota, As in 2021

Numbers, statistics as in 2022 – 23

August 27, 2023: The Times of India

1.8 lakh

Students who stay in Kota between July and January of the next year – the peak season for coaching. They increase the town’s regular population of 14.7 lakh by over 12%. Most of them are from UP, Bihar, MP, Rajasthan, Haryana, Punjab, Maharashtra, Gujarat, West Bengal and Odisha.

2,500

That’s the number of registered hostels in Kota. They accommodate altogether 1.2 lakh students who pay Rs 7,000-30,000 per month for stay and food. About 80% of the boarders have a room to themselves. As demand grows, accommodation for 15,000-20,000 students is added every year. These days, 1BHK flats and studio apartments are much in demand as some parents – mothers, especially – choose to camp in the city during the coaching season. Every year, 4 lakh-5 lakh parents visit Kota – practically every second visitor – contributing Rs 100 crore to the travel industry.

50 lakh

It’s a coaching town, so there’s a huge market for books. The students buy around 50 lakh books worth Rs 40 crore-50 crore every year. The per person expenditure on books and stationery comes to Rs 8,000-10,000. The students also need uniforms, so about 6 lakh uniforms – worth Rs 500-600 each – are sold every year. And because they are teenagers, they occasionally buy more fashionable clothes wear also, together spending about Rs 60 crore every year.

₹50,000

Food is the third major cost for students after tuition and accommodation. Students living outside hostels as paying guests spend Rs 40,000-50,000 every year on board. Public transport – autorickshaws, vans and buses – is not too costly, with students paying Rs 30-50 a day, but about 20,000 buy new bicycles every year.

₹5,000cr

The city’s coaching business is worth up to Rs 5,000 crore per year. There are six large institutes with more than 5,000 full-time students each, and numerous smaller ones. Yearly fees range from Rs 40,000 to Rs 1.3 lakh. Coaching creates 2 lakh jobs directly and 1.5 lakh indirectly. The government gets up to Rs 700 crore in taxes.

₹2,00,00,000

Some 20-30 ‘star’ teachers earn over Rs 1 crore a year. The highest package is Rs 2 crore. Even the starting package for the 4,000-5,000 teachers at the coaching institutes is Rs 8 lakh or Rs 67,000 a month. Roughly 10% of the teachers are IITians. Data sourced from Rajasthan government, coaching institutes, Kota police, chartered accountants, transporters, realtors, shopkeepers and hostels

The coaching institutes of Kota

The Times of India, June 8, 2016

Anindo Dey & Shoeb Khan

The stress chambers of Kota coaching

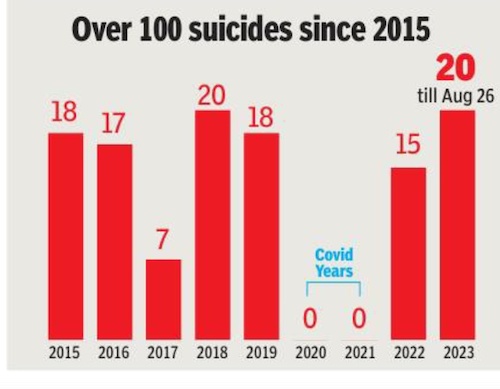

In 2015, 17 students committed suicide. Anti-depressants sell like hot cakes. Students are struggling to cope with growing stress levels. The police, however, are not perturbed. Since 2010, 69 students enrolled with the 130-odd engineering or medical coaching institutes in the city have taken their own lives, says Kota SP Sawai Singh Godara. Almost 70% of these deaths were a result of the student being unable to cope with the pressure of studies, he says. The remaining ended their life over disappointment in their love life or over family issues. “You can't say there is a surge in cases of suicide among students. If the annual number of 14 or 16 cases of suicide go up to 20 or 24, that will be a surge,“ says Godara, adding that the `suicide rate' is within `global norms'.

NO SCREENING TESTS

There is alarm in the city .District collector R K Surpur in March 2016 directed the institutes to re-start screening tests that can provide students and parents with a fair assessment of the child's aptitude.Screening tests were prevalent till 2005-06, but disappeared as coaching centres set up shop and competition turned stiff. The result: even students with scores less than 50% in Class XII are also being enrolled.

The state may be mulling ways to make the screening test mandatory, but coaching institutes insist they will introduce entrance tests if the same rule applies to coaching institutes in Hyderabad, Chennai, Bangalore, Pune and Delhi.

TOUGH FOR THE MIDDLING STUDENTS

Students like these two girls make up a sizeable section of students stuck in Kota: living out their parents' dreams. Parents willing to sink big money in the pursuit: over Rs 6 lakh in some cases for a two-year stint at being coached to appear for a qualifying exam to a medical or engineering college.

Hostels range from the dingy, dimly lit room at Rs 1,000 per month to those that serve food of choice, a snooker table and two holiday packages per year, all at Rs 25,000 per month.

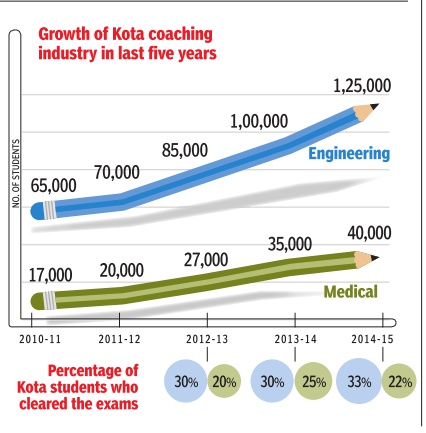

It's a far cry from the Kota of the 1980s. After the collapse of J K Synthetics, the coaching institutes became a lifeline for the struggling city . But with the success of the pioneers, the town attracted a host of players, even foreign ones, promising students' victory in killer competitions.

As coaching centres mushroomed in the last 10 years, and coaching became an `industry', many of the lesser known tutorials took on students without any qualifying test, irrespective of a child's current school standing.For the 60,000 children, between ages 14 and 18 who end up in the city every year, there is admission for all irrespective of marks, in many of the institutes.

KIDS ON ANTI-DEPRESSANTS

The stakes are high, students burdened with the need to fare well, and bring their parents “return on investment“. It explains why former member of the district child welfare committee Vimal Jain is a disturbed man. His medicine shop has seen a rapid increase in students buying antidepressants on prescriptions from psychiatrists. He says, “How can those getting 50% compete with the 90-percenters?“ Following reports of suicide, Surpur instructed the institutes to institutionalise systems to deal with depression and related issues among their students. “These kids may never have ventured out of their house but here they have to interact with everyone -from the shopkeeper to the washerman. Even the food they eat may not be their natural diet. It is how they break; simply being unable to cope,“ he says.

The direct feed to parents of scores on their cell phones is a nightmare. Further, institutes segregate weaker students from the better-performers; teachers tasked to spend more time grooming the better ones so that an institute's scores a higher `success rate'. If that pushes a child over the edge, to the point of killing himself herself, it's just another tragedy .

Successful alumni give back through scholarships, coaching

There’s a positive side to the Kota model, February 15, 2018: The Times of India

Successful alumni and institutes from this town are giving back by offering scholarships and coaching to the underprivileged

Med aspirant ends life’, ‘Drugs, sex, stress in Kota’…India’s coaching hub gets a lot of bad press. But in Rajasthan’s Sojat town, they know Kota as the place that helped Ramchandra Sankhla crack the IIT exam and get to the US to work in one of the world’s top companies.

Born into the family of a daily wage earner, Sankhla, 25, grew up in a single-room home in Sojat. Seeing his calibre, a teacher in his government school urged him to shift to Kota for IIT-JEE coaching. But cost was a major worry. “We borrowed some money and headed for Kota, unsure whether we will be able to pay it back,” Sankhla tells TOI over the phone from the US.

Sankhla needn’t have worried. A year later he was picked for a scholarship; he qualified for IIT-Roorkee; Google hired him and after a stint at Bengaluru, he was sent to Seattle.

Sankhla is one amongst the numerous IITians that Kota’s coaching institutes churn out annually. Many, like Sankhla, came from underprivileged backgrounds – the son of a coolie at a railway station, a NREGA worker from Bihar, a girl child bride… In Kota, they found both support and success.

“Some successful alumni have been granting scholarships to needy students. Vatsalya Singh, son of a welder from Khagaria, Bihar, hit the headlines after he was hired by Microsoft with an annual package of Rs 1.2 crore in 2016. “Had Kota not supported me, I would have perhaps become a welder too,” says Singh. Today, he is helping others achieve their dreams.

The city’s coaching expertise is also being used to bring change in Naxalite-affected Chhattisgarh and insurgency-hit Kashmir. Pramod Maheshwari, director of Career Point says, “Our collaboration with the Chhattisgarh government in providing coaching in Naxal-hit areas and collaboration with local partners in Srinagar is bringing the children of the region into the mainstream.”

Suicides, pressures, depression

Suicides, 2015 – 23

Mudita Girotra & Shoeb Khan, TNN, August 27, 2023: The Times of India

From: Mudita Girotra & Shoeb Khan, TNN, August 27, 2023: The Times of India

The pressure of IIT coaching in Kota is too much for her, but if she quits and returns home, her mother will marry her off. Sometimes, this UP girl feels so desperate that she slashes her wrists. Experts who have studied Kota’s suicide problem say this feeling of being trapped is the trigger in most cases. Dinesh Sharma, head of the mental health department at Kota’s government nursing college, recently published a paper on the risk factors for suicidal tendencies in youth. His key finding based on interviews with 400 coaching students is that academic pressure – defined as the inability to keep up with teaching in coaching institutes and schools together – is the chief cause of suicide in Kota. Family pressure comes next.

Burden Of Expectations

The UP girl seems to be crumbling under a combination of academic and family pressures. Dr M L Agarwal, a veteran psychiatrist who runs a helpline for students in Kota, has treated the girl and dozens of other stressed students. He says she is schizophrenic. “Her family knows…the medication had started in Lucknow. Yet, they dropped her here.” Such ambitious families aren’t rare. Nidhi Shrivastava, a counsellor at Resonance coaching institute, remembers a parent from Kolkata who asked her, “My child will clear IIT, right? Or NIT at least?”

Pramila Shankhla, one of Agarwal’s three counsellors, says, “Har parent ka ek hi sapna reh gaya hai ki bachcha doctor ya engineer bane (every parent wants their child to be a doctor or an engineer). Most kids are burdened with parents’ expectations.”

Kota superintendent of police Sharad Chowdhary also keeps turning over this question in his mind: “Why aren’t parents concerned?” He says stress builds up among coaching students for various reasons: “They are away from their parents, school, friends, homemade food…. There are long study hours and no play. When they come here, their rankings get affected. Those who scored 90% in their hometown score merely 60% here.”

System Multiplies Pressure

The way coaching institutes operate also combines the two pressures. Sharma’s research shows the weekly test is the most stressful time for 90% of students: “The result is declared on the same day or the next day, which contributes to a change in behaviour.” But things get worse when the results are forwarded to parents. They worry why their child, who ranked in the top tier of their town, is now lagging behind, says Agarwal. The churn in rankings and the preferential treatment for star performers also affect students psychologically. “Earlier, low scorers used to be in a separate batch. Now, there are separate batches for top scorers. They are taught better in a star batch,” he says.

It Gets Worse With Time

Sharma’s research shows stress builds up among coaching students with time. Those who have spent less than three months in Kota are the least stressed. Whereas class 12 students who have stayed more than three months, and whose scores in weekly tests are not satisfactory, are highly strung. But there’s a class angle to this anxiety. Sharma has found that dejected students from loweror middle-class families are more likely to commit suicide because they feel guilty about wasting scarce family resources. He says even when students realise they are not cut out for Kota, their families pressure them to continue because they have paid the tuition, hostel and mess fees in advance.

Watch Out For Signs

Kota’s teaching methods won’t change in a day but that does not mean student suicides are inevitable. Agarwal says, “Suicide doesn’t happen all of a sudden. There are many clues before it.” A student skips classes and meals, appears morose and struggles to concentrate. Chowdhary agrees. He says the boy who committed suicide on the night of August 15 “had not been attending classes for two months... wasn’t scoring well.”

So, what’s needed is awareness about these signs. “Faculty and hostel staff should be trained compulsorily to observe any behavioural changes in a child,” says Agarwal. It would help if parents informed institutes about the mental health issues and medication of their child at the time of admission, he adds.

Why Kota is so killing

The Times of India Jan 03 2016

Akhilesh Singh

18-hour study schedules A brutal sorting system that segregates `average' students No fee refund policies for those who want out `We can't take it anymore.

Our parents have told us to return home only after cracking IIT-JEE,“ said two distressed young students to psychologist Dr ML Agarwal in Jawaharnagar, Kota. The boys were both from Bhatinda, Punjab, where they lived in large joint families.They found themselves unable to cope in their new environment, with daily tutorial classes, and having to study for up to 18 hours a day . “It took months of therapy at a rehabilitation centre, and the involvement of their families, to restore them,“ says Dr Agarwal.

These breakdowns are all too common, across a city that reinvented itself in the late '90s as coaching hub for the hyper-competitive engineering and medical school exams. Roughly 1.6 lakh teenagers from the surrounding states flock to Kota's coaching institutes every year, paying between 50,000 and a lakh for annual tuition. Some begin early , as coaching centres also run ghost schools where they enroll middle-school students. In a few institutes, they are taught by IIT alumni, who claim salaries of Rs 1.5-2 crore for their expertise. Neither coaching centres nor hostels have exit policies or refunds, so for students who borrow money to come to Kota, the stakes are even higher.

Most students live in rented rooms with minimal facilities. They may desperately dream of IIT, but many of them are unprepared for the psychological costs. Kota has now become a byword for student suicides. A 14-year-old boy killed himself recently , the 30th suicide last year. Purushottam Singh, whose nephew Shivdutt committed suicide on December 22, is in tears as he talks of the boy . Back home in Kollari village, Dholpur, Singh says, “there were high expectations of him. His family and neighbours had already started calling him doctor sahib.“

The parents of 17-year-old Suresh Mishra (name changed), from Vidisha, now regret having sent him to Kota. “It started with headache, fatigue and bed-wetting. He now suffers from blackouts, partial memory loss and occasional hallucinations,“ says his father Mukund.

Around the world, student burnout is caused by high rates of physical and emotional exhaustion, a sense of being depersonalised, and a shrunken sense of personal achievement. Kota is a cauldron for all these feelings, with other factors like the fear of letting down one's family , or not having any career alternatives.

All around Kota, the message is to excel, or be left behind. Billboards celebrate success and star students. Entry into IITs or the other engineering and medical schools is seen as the only measure of worth. Coaching institutes, though, admit anyone who can pay the fee. Then begins the brutal sorting of students into different batch es on the basis of their performance. Those who lag in their studies live in terror of these internal assessments, and struggle with their sense of inadequacy . Some are doubly challenged, with the Class XII board and the competitive exams.

The problem, though, is that while Kota's coaching centres can find and hone smart stu dents into the perfect JEE test-takers, they are thrown by “weakness“ in students. Their performance criteria does not factor in vulnerability or burnout at all, making it hard for students to seek help.As Naveen Maheshwari, the director of Kota's largest coaching institute puts it, “average performers are bound to fail“ in this competitive place. “In such an environment, parents should understand that IITs and AIIMS are not the end of the world. They should stop imposing their own dreams on children.“

And yet, the idea that coaching centres have a responsibility for the mental wellbeing of stu dents in their tutelage is only now dawning on them. Maheshwari now plans to institute ran dom silent psychometric tests to detect vulner able students who can be kept under watch.

However, he claims that students get even more depressed if their parents take them back home.

Meanwhile, jolted by the serial suicides, the district administration is also awakening to its responsibility. Kota collector Ravi Kumar, says, “We have taken some steps, like an advisory to coaching institutes to screen students for apti tude. We are setting up a helpline to counsel students.“

Bihar Tiger Force

The Times of India, Jun 08 2016

On May 13, 2016, in one of the most violent incidents in the history of Kota involving students, a group of nearly 50 coaching students, part of a group called the Bihar Tiger Force, stabbed to death a 19-year-old student Satya Prakash `Prince' and another student on May 13. It brought to the fore the other strand of the Kota story .

About 1.50 lakh to 2 lakh students in the age group of 14 to 19 years are enrolled in various coaching institutes in Kota.Around 60,000 make their way to the city every year, about 25,000 from Bihar alone.

The Bihar Tiger Force are the self-styled `helpdesk' for these newcomers.

They receive students at the station, and help them with accommodation and recommending coaching institutes as well. All for a fee of Rs 500. A typical hostel here is an apartment building whose owner rents out the flats. Members of the Bihar Tiger Force are often the mediators. If an owner rents out the apartment building for say , Rs 60,000 per month, to the BTF, the group rents out the apartments to the newbie students, making a healthy cut on the deals.

The BTF is not the only such group, but is the most powerful in the city . At its helm are not students preparing for any test, but those who have been unsuccessful in repeated attempts --well past age 19: the upper limit for appearing in the IIT entrance test. They have stayed on in Kota, making a `livelihood'.

Following Satya Prakash's murder, the police have arrested two members of the BTF.Hostels have been alerted to tell police about all above-19 residents on their premises.

Health issues with students

The Times of India, Sep 05 2016

Shoeb Khan

Poor health stressing out coaching students in Kota

Investigations reveal that due to irregular eating habits and unhygienic consumption of fast food, the immune system of the students weaken, causing a miss on their studies.

This is turning out to be the one of the major reasons for stress, say clinical psycho logists, who submitted their preliminary report to the district administration of Kota.

The report was sought by district collector Ravi Kumar Surpur after he held a meeting with clinical psychologists this week to find out reasons for stress among students, which in extreme cases lead to suicides.

A high-level meeting, pre sided by chief minister Vasundhara Raje, was earlier held in Jaipur to contain suicides in Kota. The meeting was attended by 21 psychologists with experience of handling students at coaching centres.

Sex, sleep-deprivation, loneliness, weight loss, acidity, anxiety/ 2018

Self-harm, substance abuse, bullying, sexual experimentation and the possibility of pregnancy, sleep-related issues, loneliness, weight loss, acidity and anxiety are common among students in Kota, the coaching class capital of Rajasthan famous for offering preparatory courses to IIT hopefuls, a report by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences has said.

The report, submitted recently to the Kota district administration which had commissioned a study to find out reasons for student suicides, has a suggestion for parents: “Do an initial recce, if possible, to understand the atmosphere of Kota. It is not the best place for all children...”

‘49% of respondents feel nervous, scared & worried’

The study has also suggested ways to ease academic stress. Class sizes in coaching academies could be cut to a fifth. Advertisements on exam results could reveal the truth instead of throwing up fantastic numbers. Recreational activities such as music and dance could be woven into the rigorous competitive exam preparation timetable, and batches may no longer be segregated based on academic performance.

Between 2013 and May 2017, 58 student suicides were reported at coaching centres in the district, show police records, which however give no information on attempted suicides. In fact, between 2011and 2014, suicides in Kota due to failure in exams made up the highest percentage of such deaths among 88 Indian cities considered for the study.

Every year, approximately 1.5 lakh to two lakh students come to Kota to realise their dream of getting into an engineering or medical college. Who are these students — mostly boys and a few girls? What is a day like for them? What do they eat? What academic pressure do they face? How does Kota treat them?

The researchers — dean of the TISS school of human ecology, Sujata Sriram, assistant professor Chetna Duggal, counsellor Nikhar Ranawat and counselling psychologist Rajshree Faria — looked into all these questions, with the respondents giving replies on a “perceived stress scale” framed for the survey. “49% of respondents cited feeling nervous, worried and scared; 42% mentioned that their friends were nervous, scared and worried. 37% said they felt easily annoyed or irritable, followed by 32% who said they were upset or sad for most part of the day or for many days at a time,” stated the report.

“Feelings of hopelessness and helplessness were expressed by 28% respondents; another 28% expressed feelings of worthlessness. Serious concerns of feeling like a failure and letting down the family were expressed by 27% of the respondents.”

Many students reported sleep-related problems, of not being able to wake up or falling asleep or staying asleep. Problems of constantly feeling tired were mentioned, as were those related to eating, food, loss of appetite and weight. While digestion trouble figured on the list of issues, around a third of the female students spoke of problems with their menstrual period, the report stated.

The researchers noted that very often, messes bought the lowest quality of vegetables — leftover stock or stock not considered suitable for sale due to the price factor. “This kind of stock was colloquially referred to as “messquality” vegetables. Students had concerns regarding the quality of the food served (uncooked rice, watery dal and stale food), lack of healthy food available in canteens, hostels and messes, lack of hygiene in kitchens, hostels providing good-quality food only in the beginning of the session and differing palates.”

Similarly, hoardings that welcomed many to Kota made “inflated claims”. While each coaching centre advertises the names, rank and photographs of successful candidates, the actual percentage of success was not disclosed to researchers.

The report recommended that there should be accurate display and communication of the coaching centres’ success rates in IIT-JEE, NEET, and other entrance exams. Again, any form of advertisements by coaching centres should incorporate a disclaimer stating that studying in that particular coaching centre does not guarantee admission into medical and engineering colleges, it said.

Other proposals include reduction of the class population of 200 to 40 each, appointment of trained counsellors and clinical psychologists, sensitisation of teachers on mental health issues, availability of on-call doctors, creation of a recreational room for games, screening of movies, formation of peer mentor groups and removal of pigs and stray cattle.