Education, annual reports on the status of: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The status of school education in India

Rural schools: 2009-14

Jan 14 2015

Rural schools high on enrolment, but low on learning levels: Report

Akshaya Mukul

Pratham's 10th Annual Status of Education Report -the country's biggest private audit of elementary education in rural India -released Tuesday has a similar story as in previous years: rising enrolment, poor learning levels in reading, mathematics and English and growth in number of private schools. ASER also says improvement in school facilities -pupil teacher ratios, playgrounds, kitchen sheds, drinking water facilities, toilets -continues. HRD ministry is going to strongly dispute ASER's claims on falling learning outcomes since government's own report gives a different picture.

With Pratham gaining worldwide presence -from Pakistan to Africa -the ceremony , again like in the past, was a glittering event attended by industrialists, entrepreneurs and even chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian. Report for 2014 done after survey of 16,497 villages, 5.7 lakh children in over 3.4 lakh households across 577 districts says that for the sixth year in a row enrolment levels are 96% or higher for the age group of 6 to 14.

Rural schools, 2014-16

Pratham audit paints mixed pic of rural education, Jan 19, 2017: The Times of India

A private audit of school education in rural India paints a mixed picture of hits and misses increase in enrolment, no increase in private school enrolment, improvement in reading ability and arithmetic, but not so much in reading English.

After a gap of a year, Pratham's 11th Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) was unveiled on Wednesday in the presence of Delhi education minister Manish Sisodia and chief economic adviser Arvind Subramaniam. The survey was carried out in 17,473 villages, covering 3,50,232 households. Children's attendance shows no major change since 2014. Also, the proportion of small schools in the government primary school sector continues to grow.

The report that largely looks at enrolment pattern and learning abilities highlights that at the all India level, enrolment in the age group of 614 has marginally increased from 96.7% in 2014 to 96.9% in 2016. Similar increase can be noticed in the enrolment for the age-group of 15-16 from 83.4% in 2014 to 84.7% in 2016.

In states like Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and UP, the fraction of out-of-school children has increased between 2014 and 2016. In MP, it has been the highest from 3.4% to 4.4%. In three states, the proportion of out-of-school girls is higher than 8%. This includes Rajasthan (9.7%), UP (9.9%) and MP (8.5%).

There has been no increase in enrolment in private schools in the last two years.Enrolment is almost unchanged at 30.8% in 2014 to 30.5% in 2016. Gender gap in private schools has decreased slightly from 7.6 percentage points to 6.9 percentage points.

As for learning ability , na tionally the proportion of children in Class III who could read at least Class I text has gone up slightly from 40.2% in 2014 to 42.5% in 2016. Overall, reading levels in Class V are almost the same year on year from 2011 to 2016. However, the proportion of children in Class V who could read a Class II-level text improved by more than five percentage points from 2014 to 2016 in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tripura, Nagaland and Rajasthan.

However, in Class VIII, reading level has shown slight decline since 2014, from 74.1% to 73.1%. Except for Manipur, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, reading level does not show much improvement.

In 2014, nationally 25.4% of Class III children could do a two-digit subtraction which has risen slightly to 27.7% in 2016, mainly in government schools. However, in Class V , the arithmetic levels of children measured by their ability to do simple division remained almost the same at 26%.But among Class VIII students, the ability to do division has continued to drop, a trend that began in 2010.

Ability to read English has slightly improved in Class III but relatively unchanged in Class V . In 2016, 32% children in Class III could read simple words as compared to 28.5% in 2009. Worrisome is the gradual decline in upper primary. In 2009, 60.2% in Class VIII could read simple sentences in English; in 2014, this was 46.7% and in 2016, it has declined to 45.2%.

2017, 2018

From: Ishita Bhatia & Ardhra Nair, Why parents prefer these govt schools to pvt ones, January 23, 2019: The Times of India

From: Ishita Bhatia & Ardhra Nair, Why parents prefer these govt schools to pvt ones, January 23, 2019: The Times of India

In The Absence Of Adequate Infrastructure, Some Rural Schools Are Making The Most Of What They Have, And Getting Results

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) paints a grim picture of senior school students who can’t do basic math and juniors who don’t recognise alphabets. But there are schools that have set a blazing example despite all the odds — inadequate infrastructure, shortage of teachers, poor mid-day meals. Innovative, courageous and inspiring teachers have at times made such a difference that parents are shifting their wards from private schools into these nononsense classrooms.

In UP, some of these exceptional schools are optimally utilising technology and have students who speak perfect English and score consistently well in exams. Like 10-year-old Aisha (who uses only her first name). She left a private school because her family did not want to spend “too much on the education of a girl”. While her brother, Taasim, continued to study in the earlier school, in 2017, Aisha was admitted in Class IV at the Primary School-I at Phaphunda village in Meerut. Soon, she started excelling in studies. Three months later, the school principal insisted that Aisha’s family conduct a competition between Aisha and her brother. Aisha fared better. Now Taasim is also studying in the same government school as his sister, in Class V.

At least 50 students from six private schools within a 6km radius of Phaphunda have taken admission in this government school in the last four years. So confident are school officials about ensuring quality that they have also instituted a ‘money-back policy’ for parents who are not satisfied with the performance of their wards. Enrolment has doubled from 190 in 2014. The school has an activity room with a projector, laptop and printer as well as colourful flex boards in classrooms.

At Primary English Model School in Kamalpur, Yatika Pundir, assistant teacher, said, “In 2015, our school was among the first two of Meerut district that were shortlisted to be converted into English-medium schools.” The challenge was to get rural students to switch to English education. The teacher achieved this through interactive activities that drew the children into the learning process.

But this is not the picture at all government schools in UP. One look at some of the schools lays bare the hurdles they face, struggling with teacher shortages, lack of basic facilities in classrooms, poor quality of mid-day meals and rickety buildings.

As UP schools make efforts to improve, far to the southwest, in Pune district of Maharashtra, Yuvraj Sangale is no longer India’s “loneliest school student”. He now has five classmates. The story of Yuvraj’s struggles and his teacher Rajinikanth Mendhe’s 40-km daily trek through hills and dirt tracks to reach him was read and shared online by many readers after it first appeared in TOI in March 2018. Yuvraj was then the only student of the zila parishad school in Chandar village of Bhor area in the district.

After readers came forward to arrange for supplies, from an electric water pump to bookshelves, a year on, this tiny settlement of 60 residents some 100 km from Pune, has a community hall, electricity supply for its school and new learning material. Yuvraj has a new teacher, too, replacing Mendhe. To reach Chandar village, Kallapa Khindiwale leaves home at Khanapur, 25 km from Pune, on Monday mornings with another teacher on a bike with groceries and books. He returns home only on Saturday morning.

“I don’t know how many of my students will study beyond Class IV or Class VIII. But I can make a difference to the first four years of their education. If I teach them right, they will learn to calculate wages, read boards of buses and buy things. They will not be cheated,” Khindiwale added.

This dogged pursuit of imparting education by teachers like Khindiwale is making an impact. ASER reveals an improvement in critical educational parameters in rural Maharashtra, now one of four states with a sustained and significant increase in learning outcomes after 2014 and an improvement of 3 percentage points or more in both 2016 and 2018.

But infrastructure still poses a problem. Villages like Yuvraj’s continue to be isolated. Road construction to Chandar has progressed only in patches. Three neighbouring villages don’t even have access roads.

The isolation daunts children seeking higher education. Yuvraj’s elder sister, Vaishali, is a Class VI student at the Mangaon zila parishad school. She starts walking from Chandar at 8 am and reaches school by 10.30 am. The nearest high school is in Panshet. “There is just one bus from Mangaon to Panshet at 6 am, for which we need to start walking from here at 3 am, in the dark, over treacherous terrain. And the bus returns only at 9 or 10 pm. A lone student can’t make this trip,” said Anil Sangale, a villager.

2018: problems and solutions

March 30, 2019: The Times of India

(With reports from Debjani Chakraborty in Jharkhand and Minati Singha in Odisha)

From: March 30, 2019: The Times of India

From: March 30, 2019: The Times of India

From: March 30, 2019: The Times of India

'Despite 97% enrolment in schools, drop out rates are high and quality of education poor. Now, Niti Aayog has recommended radical changes in the system for better education...[

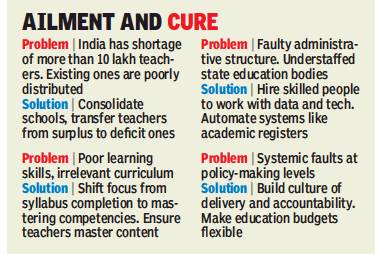

1. WHAT AILS SCHOOLS?

Problem:'

India has shortage of more than 10 lakh teachers. Existing ones are poorly distributed.

Solution:

Consolidate schools, transfer teachers from surplus to deficit ones

2. WHAT AILS SCHOOLS?

Problem:

Faulty administrative structure. Understaffed state education bodies

Solution:

Hire skilled people to work with data and tech. Automate systems like academic registers

3. WHAT AILS SCHOOLS?

Problem:

Systemic faults at policy-making levels

Solution:

Build culture of delivery and accountability. Make education budgets flexible

In the decade after the passage of the Right to Education (RTE) Act, while the target of 100% enrolment in primary schools has been largely met, the problem of qualitative improvement in learning has remained. Now, a new study released by the NITI Aayog suggests changes to traditional strategies for improving the quality of school education through a multi-pronged approach.

Despite years of effort and projects on changing syllabuses, teacher training as well as student assessments, the situation has not improved due to structural flaws. “India today suffers from the twin challenges of unviable sub-scale schools and a severe shortage of teachers which makes in-school interventions only marginally fruitful,” says the study co-authored by Alok Kumar, adviser, NITI Aayog, and Seema Bansal, director, social impact, Boston Consulting Group.

Because of an emphasis on enrolment, India adopted the strategy of building schools near every habitation, resulting in a proliferation of schools with tiny populations and inadequate resources. “Today, India has almost 3-4 times the number of schools (15 lakh) than China (nearly 5 lakh) despite a similar population. Nearly 4 lakh schools have less than 50 students each and a maximum of two teachers,” says the report. Around 1.5 crore Indian students study in such unviable schools.

Teacher vacancies have compounded the problem. The country has a shortage of more than 10 lakh teachers. The teachers that do exist are inadequately distributed. “It is not uncommon to find several surplus teachers in an urban school while a single teacher may manage 100-plus students in a rural school. Some states, like Jharkhand, have a severe teacher shortage of more than 40%,” the report maintains. States like Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Rajasthan are similarly affected.

"Shortage of teachers is a perennial problem in Odisha and is more acute in rural areas. Apart from academic work, existing teachers are also engaged in managing midday meals, conducting surveys and in administrative and election duties,” said Khageswar Pal, a primary school teacher in Mayurbhanj district.

The solutions suggested by the report include consolidating several such schools within a short distance of one another, and providing transport and allowances. “School consolidation, pioneered in states like Rajasthan and Jharkhand, has already reaped rich dividends through improved learning environments and even improved enrolment,” says the report.

The second solution is moving teachers from surplus to deficit schools, restructuring complicated teacher cadres, and increased investment in teacher recruitment through better planning and more stringent processes. Madhya Pradesh has undertaken an online teacher rationalisation process, moving nearly 10,000 teachers from surplus to deficit schools.

The next focus area is learning levels. Annual Status of Education Reports (ASER) found that nearly half of class 5 children cannot read a class 2 text. Dropout rates increase as children go through the school system. “Only around 30% of children enrolling in class 1 graduate from class 12. And of those who do, a majority do not possess the requisite skills to be readily employable,” says the report. Teachers themselves struggle with subject knowledge and the ability to teach it. Also, curriculum lacks relevance, particularly at the secondary level.

One of the solutions for this, say the authors, is moving away from just completing the syllabus to focusing on the competencies students have mastered. “Dedicated time should be carved out in the regular school day to bridge these gaps, and students should be taught based on their learning levels rather than grades. Programmes based on this strategy are being implemented in Haryana, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Odisha. These states have ensured teachers are provided concrete guidance through scripted handbooks, and students are given workbooks for rigorous practice,” the report says.

The third solution is to rethink vocational education in secondary schools. Currently, nearly 8,000 schools across the country offer one or two trades to vocationalise secondary education. But the trades are outdated.

“There should be need-based customised training of teachers at the grassroots level. A teacher weak in mathematics might be excellent in physics. We tell the students to share their knowledge. We have to do something similar amongst teachers,” said Smith Kumar Sony, currently teaching in two schools in Simdega district of Jharkhand.

The other focus area, said the authors, is in implementation of such strategies. “Communication channels between education directorates and schools are completely broken. There is little data on learning being generated in schools and fed back – so decisions on how to improve education programmes are often educated guesswork,” says the report.

“Core academic institutions— State Councils for Educational Research and Training (SCERTs) and District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs) — are understaffed and skills like curriculum design or assessment design and analysis are often missing. We need to fill these vacancies with the right people who have the relevant skills. Maharashtra has filled SCERT and DIET vacancies by selecting and training qualified teachers from within the system through a competitive process. They have also instituted a stringent annual performance review mechanism,” says the report. Employees also need to be trained to work with data and technology.

Other changes which could help include automating some systems, such as maintaining academic registers. “In Jharkhand, with real-time school monitoring data now available, the state can identify the bottom 2,500 schools and provide targeted support,” says the report. “We also need to radically rethink the culture of the education department and build one of delivery and accountability. Truly transforming public education will require bold measures like changing the way we manage public finances and making education budgets more flexible. It will need political will and a coming together of the bureaucracy, civil society and private sector.”

2017

ASER: A summary

The 2017 Annual Status for Education Report (ASER) has pessimism written all over it. It records how teaching standards are slipping fast, and could soon be under the proverbial duck’s tail. Yet, so strong is their aspiration, that the young keep enrolling; even a hopeless school exudes hope.

This is the silver lining in the dark ASER clouds. The percentage of 18 year olds in educational programmes has risen from a mere 32% in the 2001 census to an estimated 70% according to ASER’s 2017 survey. Are parents of these 18 year olds seeing rainbows at night?

This determination to see their young through schools to a better life is worth every sacrifice. Parents willingly tighten their belts past the last notch to afford private schools for their children. Consequently, the percentage of students studying in such establishments remains high and has stayed that way for some time.

Between 2010-11 and 2015-16 student enrollment in government schools across 20 Indian states fell by 13 million, while private schools acquired 17.5 million new students. In all, according to District Information System of Education (or DISE) data, about 35% of children today are in private schools – a huge jump from the 1980s when the number was just 2%.

All of this is not just an urban phenomenon. The ASER findings show that only 1.2% of youth are willing to work in agriculture and that very few young people want to follow their parents’ dreary professions. The jobs most sought after are in the army and police. Education can help in such aspirations because there is an entry test to pass.

Nor are the young satisfied in being herded into vocational schools. They aspire instead, like most middle class people, to be university graduates. Thus while a minuscule 5.3% of those between 14-18 years of age turn to vocational training, 74% aspire for a bachelor’s degree.

Workers in late 19th century Britain also wanted their children to experience the “luxury” of education. They resented the fact that the posh middle class was slotting them into vocational schools as if they were not good enough for universities. This aspirational urge was also a self-respect movement and out of it came several institutions in England such as the University of Reading.

From this a more robust middle class also emerged in Britain. Instinctively, the aspirational class in India seems to be choosing the same route. In fact, ASER records a substantial jump in the number of graduates and predicts their proportion will double in the next decade. Why should the poor be destined to vocational schools? Can they not dream bigger?

Those that still can’t make it refuse to follow their fathers’ footsteps in the mud. Agriculture is hardly an option and that is why they turn instead to non-farm occupations. No wonder, micro and small industries are sprouting more readily on village soil than wheat and rice. According to the MSME Census, there are more such units in rural than in urban India. Squatting over a loom in a windowless room is preferable to pushing a lifeless plough.

Aspirations can be a powerful motivator of knowledge. While their teachers may not deliver at par, schoolchildren are aware of a wider world because that’s where they want to make a life. Once again ASER figures show that as many as 64% could identify the capital of India. Not just that, 79% knew exactly the state they lived in and 42% could even point it out on a map.

These numbers should not be sneezed at for in developed America, according to a Gallup/Harris poll, 73% of Americans could not identify their home country on a map. Not bad at all; the aspiring Indian village kid scores higher than grown Americans.

The aspiring class in our country is running up the stairs while our so-called middle class is stuck in the lift.

2017: National Achievement Survey

Learning levels

Manash Gohain And Atul Thakur , February 24, 2018: The Times of India

Students are learning less as they move to higher classes, a survey of over 1 lakh students in government schools in over 700 districts shows. On average, a class VIII student could barely answer 40% of the questions in maths, science and social studies. The national average score for language was a little better at about 56%.

The findings raise doubts about the demographic dividend India hopes to reap because of a young population. Educationists, experts and rights’ activists are not surprised. They say this is a result of insufficient investment in public education and the government’s inability to implement the Right to Education Act (RTE) in letter and spirit.

The district-wise National Achievement Survey 2017 by National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) tested students in all major subjects in classes III, V and VIII. It used multiple-choice test booklets in maths, language, environmental science, science and social studies. While NCERT is yet to release the national and state-wise data, TOI compiled the district-wise results released so far.

In class III, students averaged between 63% and 67% marks in environmental science, language and maths. In class V, average scores fell by about 10 percentage points to 53-58%, and in class VIII, the fall was even sharper, although language scores dipped only a little. No other subject was common between these classes.

Among regions, the south did better in the early years of schooling. For example, in class III, students in the south scored more than those in the north and the east, and were behind those in the west only in language. In class V, too, they had higher average scores than the rest, but in class VIII, students from the west outperformed all other zones. The south remained ahead of the north, but scored less than the east in science and social studies.

Rural students scored higher than those in cities. Also, in classes V and VIII, OBC students outscored the general category. At all levels, average scores were lowest for ST students while SC students scored a tad higher.

Educationists say such generic surveys are futile if the results are not used to improve teaching. Prof R Govinda, former vice-chancellor of National University of Educational Planning and Administration, said, “The results don’t surprise since basic skills are not being inculcated and cumulatively, the deficit will increase. The results for the last 10 years have been the same, which means we have not done anything. The question is, how can we utilise the study results to improve the teaching-learning process. How are we going to improve teaching in the classroom?”

Ambarish Rai, national convener of RTE Forum, said government has failed to provide adequate funds for school education and implementation of the RTE Act. “RTE is a package for school development. We cannot look at any part of it in isolation.” He said the RTE Act prescribes one teacher for every 30 students at the primary level, and for 35 students in higher classes, but these have not been implemented. The country is short of 10 lakh qualified teachers, he said.

Rai disagrees with those who say that the results are fallout of the no-detention policy, and the Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation (CCE) process, both of which the Centre removed last year. “The no-detention policy has no role, as it was linked to CCE, which the government failed to implement. CCE is a scientific methodology to assess a child’s performance and explore the possibility of improvement. No detention helped reduce the dropout rate. No research or study in any country shows any relation between detention and learning levels.”

Rai said learning levels will improve when teachers are as per RTE norms. “The teacher training institutes are run by the private sector and government has no mechanism to train teachers. Improving government schools is only possible after complete implementation of RTE and the promised 6% GDP to education.”

Girls outshine boys, rural beats urban

February 24, 2018: The Times of India

Girls outshone boys

Rural stuents beat urban ones

Western India was the best region, and

OBC students did better than ‘general’ students.

From: February 24, 2018: The Times of India

One of the more surprising revelations of the district-wise National Achievement Survey 2017, is that rural students do better than their urban peers.

In class III, urban students outscore their rural counterparts in EVS but score lower in language and mathematics. At higher levels — both classes V and VIII — rural students score better in all subjects except language. Data shows the gap between rural and urban students keeps increasing in higher classes.

It may be because government schools in urban areas are so neglected that parents prefer to send their children to private schools, said Ambarish Rai, national convener, RTE Forum, an NGO. “With crowded classrooms, insufficient number of teachers, and students not getting books and uniforms on time, the government schools are in a pathetic condition.” Rai noted that the results are much better wherever the government invests in its schools. “Kendriya Vidyalayas, where the allocation is eight times higher than in other government schools, are performing better than their private counterparts.”

Girls outperform boys at all levels, but the gap narrows with age. This is probably because in both rural and urban set-ups, girls are additionally burdened with household chores such as helping in the kitchen and taking care of younger siblings.

“Social challenges for girls increase as they grow. This is a major reason why there is also an increase in the dropout rate of girls in higher classes. The Beti Bachao Beti Padhao scheme cannot run on a Rs 200-crore allocation,” Rai added. Girls, however, appear to have a definite advantage over boys in understanding of language. At all levels, the difference in average scores of boys and girls is the highest in language.

7/ 9 worst districts are in UP

Why scoring even 30% is so tough in seven UP districts, February 24, 2018: The Times of India

Of the 700-odd districts in the country, nine have such low standards of school education that students struggle to score 30% marks, and seven of these districts are located in the most populous state, Uttar Pradesh.

The ‘best districts’ in terms of learning outcomes are those where the average score is 80% in class III, 75% in class V, and 70% in class VIII. These are spread across all states, but with a higher concentration in Rajasthan, Karnataka, Kerala and Maharashtra.

The ‘worst’, though, are in UP — Shamli, Ghazipur, Kheri, Varanasi, Maharajganj, Mirzapur and Sambhal, and in Arunachal Pradesh (Changlang) and J&K (Pulwama).

Students here couldn’t score over 30% in at least five of the 10 tests in the NAS (three each for classes III and V, and four for class VIII).

Educationist Ashok Ganguly said UP’s poor showing is mainly due to the prolonged shortage of teachers and lack of activity-based learning in government schools. “There are more than 50,000 schools under the government with a huge shortage of teachers, especially in science and mathematics,” he said. Ganguly was also chairman of Central Board of Secondary Education and director SCERT in UP. “UP students shy away from taking mathematics and science class IX onwards as they have not been taught properly in the lower classes. Wherever we have science teachers, there is no hands-on activity as there are no laboratories. How can you comprehend subjects like science without learning by doing?” he added.

Terming this a systemic failure, Anita Rampal, professor and former dean at the faculty of education, Delhi University, said, “The system thinks anyone can teach. PT teachers are teaching mathematics. In Rajasthan, we have seen how girls have protested to demand teachers for their schools. We need dedicated teachers for subjects from class VI onwards and we need good teachers at the primary level.”

OBCs shine in govt schools

OBCs shine in govt schools, ST students bring up rear, February 24, 2018: The Times of India

The NAS 2017 data shows OBC students — not the general category — perform the best in government and government-aided schools. At the all-India level, OBC students outscored the general category in classes V and VIII, while being slightly behind in class III. SCs were behind both while STs had the lowest average scores.

Significantly, while the gaps are narrow to begin with and narrow further by class VIII, in language the gap widens between social groups as students move to higher classes.

The western region has a different pattern, though. SC students are the best performers in class III, followed by OBC, general and ST students, in that order.

In class V, the gap between the average scores of SC and OBC students gets narrower. In class VIII, OBC students are the highest scorers, followed by SC, ST and general students, respectively.

South is the only region where general students outperform everyone else through all levels and by larger margins in higher classes. Here, too, language remains the subject in which general students have the biggest edge.

In the eastern and northern regions general students score highest in classes III and V, but are overtaken by OBC students in class VIII.

Experts, however, warn against reading too much into these numbers. “Government schools have become the schools of OBC, dalits and minorities. They have fewer students from the general category, whereas schools should have been a place of socialisation of children,” said Ambarish Rai, national convener, RTE Forum.

“OBC and other marginalised children belong mostly to labour class and have different talents. But they don’t have equal opportunity to grow through quality learning. It is the state’s duty to provide them equal opportunity. That is why education was made a fundamental right,” added Rai.

Maths, language skills worsen from class III to class VIII

February 24, 2018: The Times of India

Across the 36 states and UTs, students’ performance in maths and language worsens as they move up from class III to class VIII. Maths is the biggest hurdle of all.

In class III, six states and UTs had average maths scores above 70%; another 17 averaged above 60%, while the remaining 13 scored 40-60%.

In class V, no state had an average score above 70% and just six averaged 60-70%, while Arunachal Pradesh alone finished below 40%. By class VIII, no state or UT averaged even 60% in maths, and 23 averaged below 40%. The minimum drop from class III was 13 percentage points, while in Nagaland, Puducherry, West Bengal and Telangana, the average maths scores fell by more than 30 percentage points.

Language shows a similar pattern. Average scores in class III were above 70% in 12 states and UTs, and between 60% and 70% in another 16. In class V, only Karnataka had an average of over 70% while nine states or UTs averaged between 60% and 70%.

By class VIII, no state averaged 70% or more, and just seven could average over 60%. In Nagaland, Jammu and Kashmir, Telangana and Mizoram, average language scores fell by over 20 percentage points between classes III and VIII.

However, experts questioned the nature of the survey. “This is purely a text-based writing assessment. Sometimes the questions are not comprehensible for students. No other methods were applied to understand their observation and lots of other things children would be doing while learning,” said Anita Rampal, professor and former dean at the faculty of education, Delhi University, who has written several chapters of NCERT’s elementary school textbooks.

“This is such a limited test. We have to first look at the nature of the question, which itself is a challenge,” she said, adding that “children understand things differently. Perhaps they are not familiar with the questions we give them.”

Terming it a ‘limited’ test, educationists said children understand things differently and were perhaps not familiar with the questions set for them

Poor infrastructure

Manash Gohain, Creaking school infra hitting kids’ learning, March 22, 2018: The Times of India

Poor school infrastructure has emerged as a key factor why children are “not learning” in government and government-aided schools across the country.

A state-wise analysis of the National Achievement Survey 2017 for classes III, V and VIII has highlighted that not only do school buildings need significant repair, the learning environment also doesn’t seem to be too conducive for teachers burdened by work overload, lack of drinking water and toilet facilities.

TOI had in one of the most comprehensive analysis of the NAS 2017 on February 24, 2018, highlighted how staff crunch, crowded classrooms and inadequate funds are to blame for poor learning outcomes in government schools as captured in the survey.

The state-wise analysis was finalised by NCERT and submitted to the ministry of human resource development recently, a copy of which is with TOI.

While across states, over 95% students like coming to school — a large number of students find the travel difficult. Lack of electricity at many schools is also one of the major factors highlighted by teachers in the survey.

2018

A summary

From: Basic literacy, numeracy skills of rural Class VIII students in decline: ASER 2018, January 16, 2019: The Hindu

From: Basic literacy, numeracy skills of rural Class VIII students in decline: ASER 2018, January 16, 2019: The Hindu

From: Basic literacy, numeracy skills of rural Class VIII students in decline: ASER 2018, January 16, 2019: The Hindu

From: Basic literacy, numeracy skills of rural Class VIII students in decline: ASER 2018, January 16, 2019: The Hindu

What is 919/6? More than half of Class VIII students do not know

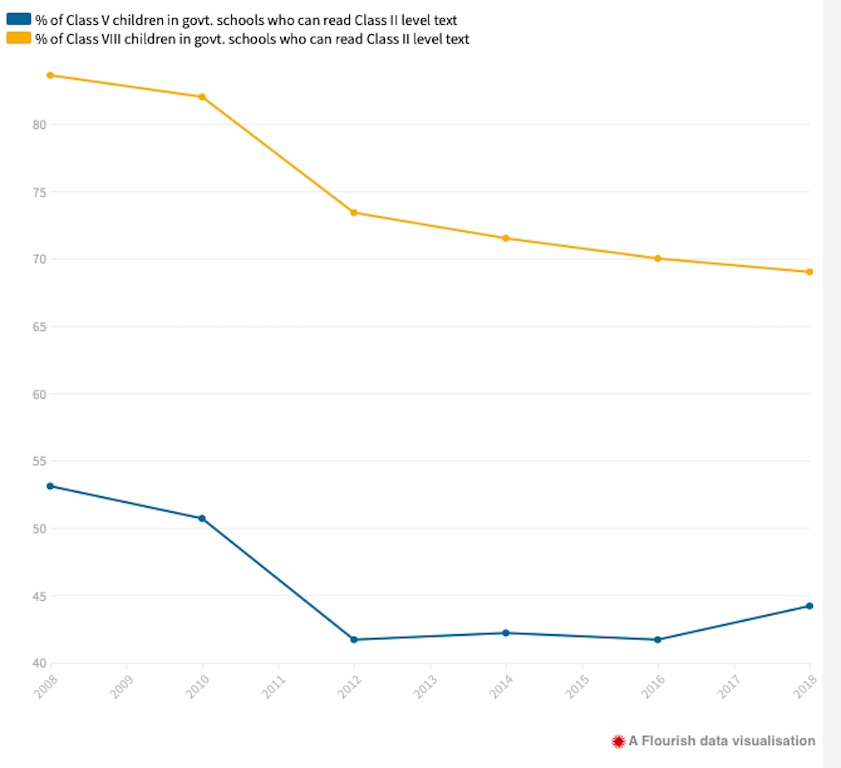

While there has been some improvement in the reading and arithmetic skills of lower primary students in rural India over the last decade, the skills of Class VIII students have actually seen a decline.

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2018, the results of a yearly survey that NGO Pratham has been carrying out since 2006, shows that more than half of Class VIII students cannot correctly solve a numerical division problem and more than a quarter of them cannot read a primary-level text.

Those figures are worse than they were a decade ago. In 2008, 84.8% of Class VIII students could read a text meant for Class II; by 2014, only 74.6% could do so, and by 2018, that percentage had fallen further to 72.8%.

Four years ago, 44.1% of students at Class VIII could correctly divide a three-digit number by a single-digit number; in 2018, that figure had fallen slightly to 43.9%.

Noting that the “additional value added in terms of math skills for each year of schooling is low”, Pratham researchers concluded that “without strong foundational skills, it is difficult for children to cope with what is expected of them in the upper primary grades”.

The picture is slightly more encouraging at the Class III level, where there has been gradual improvement since 2014. However, even in 2018, less than 30% of students in Class III are actually at their grade level, that is, able to read a Class II text and do double-digit subtraction. “This means that a majority of children need immediate help in acquiring foundational skills in literacy and numeracy,” said Pratham.

These overall percentages also camouflage wide differences in skill level between States, or even between students in a single classroom.

For example, the ASER data found that almost half of Class III students in government schools in Himachal Pradesh can read a Class II level text, while another quarter can read a Class I level text. This allows the teacher to use grade-level textbooks for most of the class, although the remaining quarter of students will need ongoing support for basic skills.

In government schools in Uttar Pradesh, however, a quarter of students cannot recognise letters yet, while another 37% can recognise letters, but not read words. Urgent and immediate help is needed for these students if they are not to be left behind.

The ASER survey covered almost 5.5 lakh children between the ages of 3 and 16 in 596 rural districts across the country. In an encouraging trend, it found that enrolment is increasing and the percentage of children under 14 who are out of school is less than 4%. The gender gap is also shrinking, even within the older cohort of 15- and 16-year-olds. Only 13.6% of girls of that age are out of school — the first time the figure has dropped below the 15% mark.

Dropouts: 2006> 18; enrolment: 2010> 18; quality: 2014> 18

Dropout rate: 2006> 18;

school enrolment: 2010> 18;

quality of learning: 2014> 18

From: January 16, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

School education in India:

Dropout rate: 2006> 18;

school enrolment: 2010> 18;

quality of learning: 2014> 18

2018: National Achievement Survey

From: Manash Pratim Gohain, Exams in classes V, VIII to return as no-detention policy ‘fails’ national test, May 28, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Government is considering passing requirements for Classes V and VIII from March 2019

NAS found that Class X students were performing worse than Classes III, V and VIII students

The National Achievement Survey (NAS) has delivered a sharp indictment of the ‘no-detention policy’ with learning outcomes deteriorating as students progress to higher classes, prompting the government to consider passing requirements for Classes V and VIII from March 2019. The fresh thinking follows the NAS revealing that Class X students of state boards were struggling to get even 40% of answers right in maths, social science, science and English, doing better only in Indian languages.

Conducted in all states and Union Territories with a sample of 15 lakh students, the NAS, which was carried out on February 5, 2018, found that Class X students were performing worse than Classes III, V and VIII students — evidence of the problem of poor learning being simply moved up the chain to higher classes. If 64% of Class III students of state, CBSE and ICSE boards answered a maths question right, the score was down to less than 40% for all state boards barring Andhra Pradesh for Class X. The NAS for junior classes saw the percentage dipping to 54% in Class V and 42% in Class VIII.

Outcomes for English reflected a similar declining graph. The average of students giving correct answers dipped from 67% in Class III to 58% in Class V and 56% in Class VIII to no state barring Manipur crossing 42% in Class X. “The no-detention policy has not worked. It was conceived in haste and poorly implemented. The government does not want to put students under more stress by compulsory grading in junior classes, but a passing requirement might be needed in Classes V and VIII,” awell-placed source said.

The problem, sources associated with the survey said, was one where the no-detention policy under Right to Education Act saw exams being devalued. “Teachers lost leverage over students and also interest in bothering about outcomes. Students lacked motivation to prepare for exams as there was neither reward nor failure attached to results,” said the source.

The result, as starkly brought out by the NAS, was a growing percentage of underperforming students as they moved to senior classes. The reintroduction of boards at Class Xis likely to deliver a shock in terms of poor pass percentages. Officials pointed to the high number of “failures” in Class XI in recent years as schools’ screen for the Class XII board exams, resulting in protests by students and parents.

Without meaningful evaluations, teachers and school managements are tempted to “kick the can down the road”, even as attempts to enforce exam discipline were met with resistance from students and parents. The no-detention policy, without adequate attention to ensuring learning outcomes, meant that exams were treated in a cavalier manner. It was only in modern Indian languages that state board students in as many as 19 states and UTs crossed the 50% correct-answer mark. This might indicate a higher proficiency in mother tongues. Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan came across as better performing state boards. Delhi had the highest overall score of 45.6%.

2020

A summary

Anash Gohain, October 29, 2020: The Times of India

From: Anash Gohain, October 29, 2020: The Times of India

Schools might have been shut, but children continued their learning even during the pandemic. Despite the inequalities and digital divide, the 15th Annual Status of Education Report (ASER 2020) Rural reflected the res ilience shown towards learning as 11% of all rural families bought a new phone since the lockdown began and 80% of those were smartphones. Also more children joined government schools than private schools.

Unlike the previous ASER reports which focussed on learning outcomes, the latest report deals with the process of learning because of the prevailing Covid-19 situation. This is the first time the survey has been conducted over telephone.

While the closure of schools since March 2020 impacted campus academic activities, the good news was that 70% of the community came out to help the school support system. The data demonstrated that almost three quarters of all children receive some for m of lear ning support from family members. Notably, even among children whose parents have not studied beyond primary school, family members provided support with older siblings also playing an important role in helping the younger children learn. The report called for developing a digital pedagogy and to prioritise efforts to break the digital divide. Just around 56 % households with children enrolled in government schools have smartphones, while 74.2% of households who send their children to private schools have smartphones.

Citing another example of the existing divide, the report said children in private schools were much more likely to have accessed online resources than those in government schools. For example, 28.7% of children enrolled in private schools had watched videos or other pre-recorded content online, as compared to 18.3% of government school students.

Access to learning materials and activities too need attention as only 33.5% of all government school children received materials or activities, as compared to 40.6% children in private schools. In fact, in states like Rajasthan (21.5%), UP (21%), and Bihar (7.7%), less than a quarter of all children had received any materials.

A majority of the roughly two-thirds of all households that reported not having received learning materials during the reference week said they hadn’r received any from the schools. WhatsApp emerged as the most preferred medium via which the children got materials/activities.

See also

Education, annual reports on the status of: India

Education: India (covers issues common to all categories of Education) <> Education: India, 1911 <> Engineering education: India <> Education, annual reports on the status of: India<> Higher Education, India: 1 <> Medical education and research: India <> Primary Education: India <> School education: India (covers issues common to Primary and Secondary Education) <> Secondary Education: India <> Indian universities: global ranking <> Caste-based reservations, India (history) …and many more.