Architecture (traditional): India

(Created page with "{| Class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> </div> |} [[Category:Ind...") |

Revision as of 21:07, 16 June 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Water and architecture

From: Arjun Kumar2, Royal Lessons: Make Water Foundation Of Architecture, June 16, 2018: The Times of India

Modern-day building projects don’t seem to think twice about filling up lakes and water bodies to reclaim land at great cost to the environment. But take a look at the past and we have impressive examples of architecture that is in harmony with water and respects the precious resource

There are moments in India’s peak summer when you begin to suspect if the airconditioning is effective. And it is precisely at these moments that one also tends to wonder how those in earlier days managed to survive the merciless heat of an Indian summer.

Search a little and you would find that royals and the elite of the past used their common sense to beat the heat and leveraged the most obvious resource available — water. Across geographies, dynasties and time periods, structures built in proximity to water bodies enabled them to escape the heat, dust and intrigues of their capital.

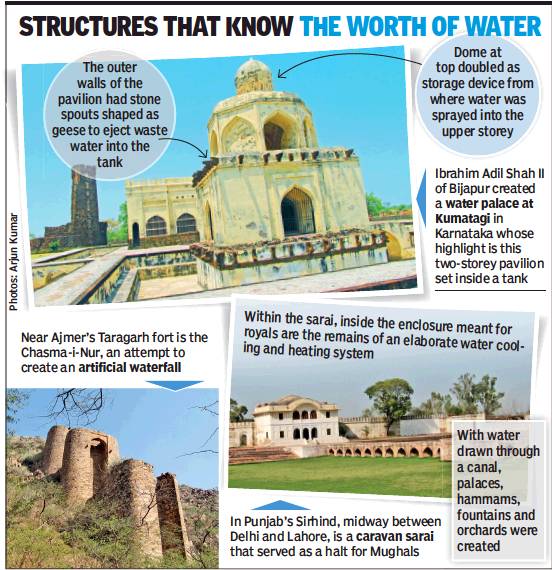

Take for instance Ibrahim Adil Shah II of Bijapur, Karnataka. Towards the end of his long reign (ending 1627), he erected a water palace in Kumatagi, an isolated spot 20km east of his capital. Here, a complex system of hydraulic works on a lake provided water for a series of over-and-underground tanks, cisterns and fountains. The highlight was a two-storeyed pavilion set inside a tank. The tank is now dry, but one can still imagine the poetic Bijapur ruler composing verses in his cool summer palace.

More than 2,000km north, something similar is visible in Sirhind, Punjab, the site of a large caravan sarai that served as a halt for the Mughals. Here, inside the enclosure for the royals, are the remains of an elaborate water cooling and heating system. Most significant is a Sard Khana in which a system of water tanks with pipes running through the walls kept the building cool in peak summer. A causeway connects two parts of the enclosure. At one end is a set of rooms that formed a hammam or bathing area. The presence of furnaces and terracotta pipes running through the walls indicates the availability of piped hot water.

Similar structures, leveraging water to alleviate the heat, dot the country. Udaipur’s Lake Palace is iconic, Jaipur’s Jal Mahal is well known, while Narnaul’s (in Haryana) is quite obscure.

In Mandu, near Indore, the Khaljis built the celebrated Jahaz Mahal between two artificial water bodies. Delhi has its own Jahaz Mahal, in Mehrauli. These are just a few examples, out of hundreds, of how Indians centuries back not just respected but also celebrated water.

Today, neglect and uncontrolled growth of human habitations has caused water bodies near most of these pavilions to go dry. But even in their state of ruin, these pleasure pavilions hold lessons for modern-day architects and town-planners — to innovate and build in harmony with water rather than in defiance of nature.