Architecture (traditional): India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Arches

Hindu, Muslim arches

HARSHA V DEHEJIA, December 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: HARSHA V DEHEJIA, December 12, 2020: The Times of India

The human hand is both the most functional part as well as the most artistic part of our body, capable of performing multiple functions, expressing a variety of emotions, the prehensile thumb holding everything from a brush, pen and hammer, capable of being decorated with jewellery and henna and above all, conveying a world of feeling through its touch, whether as one of friendship, love or blessing.

Perhaps the most evocative part of an icon of the deity is the hand, the abhaya mudra and the varada hasta, the hand that holds a lotus as well as the spear, the hand that uplifts the mountain as well as the kamandalu. It is the human hand that offers salutations and it welcomes.

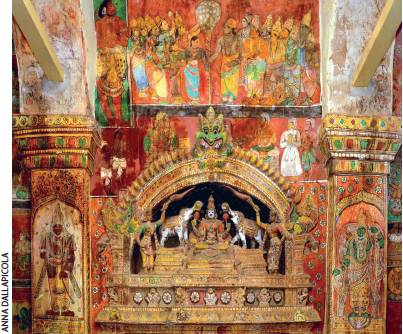

A welcoming arch is a prehistoric device and was made by people joining hands across each other and creating an arch. This is how we welcome royal guests into our village as well as the new bride into our home.This device of the welcoming arch created by the joining of hands was replicated as a structural device in ancient times and it was created by taking a branch of a tree and bending it in the form of an arch and securing it at two ends.This created an arch and worked when buildings and temples were made of wood.When we started making structures in stone, Hindu sthapatis faced an architectural hurdle as they did not know how to make a true arch.

The arch was important to us for it was a way of welcoming, and representing it in homes and temples as an architectural device. Muslims knew how to make a true arch by using a keystone in the middle and arranging stones on either side in an arch and the stones would set in place.We see these arches in Islamic architecture in India. Central Asians knew this technique and the Sultans and Mughal architects learnt it from them.

The Hindus also made an arch in their stone structures, but this was a corbelled arch where stones were cut and attached to a semicircular frame.Although the Hindu arch is not a true arch, we use it in many beautiful ways in our buildings, doorways and niches. Not only is it a beautiful architectural device that adds a wavy and sinuous touch to an otherwise prosaic structure, but always suggests the original welcome that was created by joining hands. Related to the arch is the torana the festoon, made of flowers or fabric that is placed at the lintel of a door and which also suggests ‘welcome’.

Water and architecture

From: Arjun Kumar2, Royal Lessons: Make Water Foundation Of Architecture, June 16, 2018: The Times of India

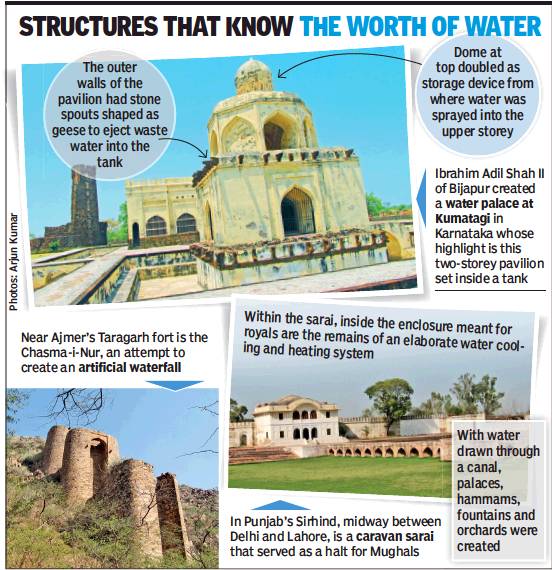

Modern-day building projects don’t seem to think twice about filling up lakes and water bodies to reclaim land at great cost to the environment. But take a look at the past and we have impressive examples of architecture that is in harmony with water and respects the precious resource

There are moments in India’s peak summer when you begin to suspect if the airconditioning is effective. And it is precisely at these moments that one also tends to wonder how those in earlier days managed to survive the merciless heat of an Indian summer.

Search a little and you would find that royals and the elite of the past used their common sense to beat the heat and leveraged the most obvious resource available — water. Across geographies, dynasties and time periods, structures built in proximity to water bodies enabled them to escape the heat, dust and intrigues of their capital.

Take for instance Ibrahim Adil Shah II of Bijapur, Karnataka. Towards the end of his long reign (ending 1627), he erected a water palace in Kumatagi, an isolated spot 20km east of his capital. Here, a complex system of hydraulic works on a lake provided water for a series of over-and-underground tanks, cisterns and fountains. The highlight was a two-storeyed pavilion set inside a tank. The tank is now dry, but one can still imagine the poetic Bijapur ruler composing verses in his cool summer palace.

More than 2,000km north, something similar is visible in Sirhind, Punjab, the site of a large caravan sarai that served as a halt for the Mughals. Here, inside the enclosure for the royals, are the remains of an elaborate water cooling and heating system. Most significant is a Sard Khana in which a system of water tanks with pipes running through the walls kept the building cool in peak summer. A causeway connects two parts of the enclosure. At one end is a set of rooms that formed a hammam or bathing area. The presence of furnaces and terracotta pipes running through the walls indicates the availability of piped hot water.

Similar structures, leveraging water to alleviate the heat, dot the country. Udaipur’s Lake Palace is iconic, Jaipur’s Jal Mahal is well known, while Narnaul’s (in Haryana) is quite obscure.

In Mandu, near Indore, the Khaljis built the celebrated Jahaz Mahal between two artificial water bodies. Delhi has its own Jahaz Mahal, in Mehrauli. These are just a few examples, out of hundreds, of how Indians centuries back not just respected but also celebrated water.

Today, neglect and uncontrolled growth of human habitations has caused water bodies near most of these pavilions to go dry. But even in their state of ruin, these pleasure pavilions hold lessons for modern-day architects and town-planners — to innovate and build in harmony with water rather than in defiance of nature.