Ahmedabad

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

History

The Indian Express, February 21, 2016

The city that Ahmed Shah built

Written by Shiny Varghese

Kites, hundreds of them, like memories, float and stick out in corners of the old city. They are everywhere — on tree tops, on towers, on cables. Lal Darwaza is the entry to the walled city of Ahmedabad, spanning centuries of history. On one side of the road is a colonial bungalow-turned-boutique hotel, House of MG, dating from 1924. Just opposite is the iconic Sidi Sayed Mosque, a prelude to all that the old city holds. Built in 1573, by a slave of Ahmed Shah I (after whom the city is named), the mosque is a visiting card for the city itself. You could pass it by and not realise what the fuss is about, until you arrive at the entrance, and see the intricate stone jaalis. Through the geometric squares in arched windows, slivers of the blue sky and green trees light up the dark interiors of the mosque. The “tree of life” lattice here has been used for the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Ahmedabad logo, and can be seen on many tourism brochures and advertisements.

We are at the tumultuous bazaar in the precinct of Bhadra, the fort in the old city. It was here that Ahmed Shah laid the foundation of Ahmedabad in AD 1411. Some of the most prominent structures in the precinct belong to his reign, like the Jami Mosque and Raja-Rani no Haziro (King and Queen’s tomb). On the edge of the central square is BV Doshi’s Prembhai Hall. British architect Claude Bately’s Electricity House, with its European plan and Indian elements of chajjas and jaalis, is located just before the entry to the citadel area.

“You will see flavours of different kinds in the old city,” says Ahmedabad-based architect Yatin Pandya, “It has maintained its own character, melding cultures and styles seamlessly, from the Gujarat Sultanate to the Mughals and the British.”

A group of architects and designers were on a trip to Gujarat last month, organised by the Indian Institute of Interior Designers, Delhi chapter. Pandya was our guide, anthropologist and social interpreter. He has mapped the city in his head and on paper, covering its cultural, architectural, and historical heritage. Now that it has been chosen as a contender for the Unesco Heritage City tag, they were here to assess its worthiness.

For one, the city was probably the first to have an underground drainage and water supply system, a century before urban planners came on the scene. President of the Ahmedabad municipality in 1885, and founder of the first textile mill, Rao Bahadur Ranchhodlal Chhotalal was instrumental in this futuristic move, which still serves the city more than 106 years later.

The famed pol houses of the city have been selected for their historic character, environmentally sustainable architecture, and for being socially interactive spaces.

To reach the pols, one enters through the braided streets of Dhalgarwad, the stretch from Bhadra to Manek Chowk, a historic market in the city, where a riot of colours and heady aromas hit the senses. In Manek Chowk we see an example of the morphing of space that the city is known for. The traders feed cattle every morning before they begin business to attract good luck. After which, the area expands into a parking lot, and at night when the cars vacate their spots, the space is taken up by vendors of street food.

This optimal use of space stretches into the pols too. Pol comes from the Sanskrit word pratoli, which means gateway or entrance. It was built by groups of families based on occupation, or kinskip and clan, or ethnicity. “It was not based on economic differences. So a mill owner and a worker would possibly stay in the same pol, creating mutual interdependence and respect,” says Pandya, as we arrive at Haribhakti ni Haveli.

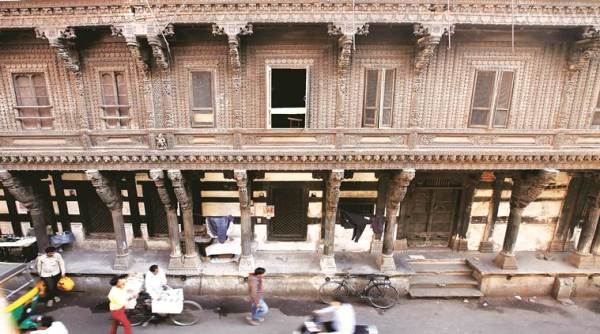

As if someone has turned down the volume, it’s quieter, cleaner and strangely not congested even though the row houses stick to one another and maintain their proximity to the street. With tiny entrances, this pol house has a wooden facade, with columns, brackets and railing details carved intricately. “Various sets of carpenters would have done numerous jharokhas, doors and window panellings, and could make my house different from yours,” Pandya says, pointing to the panels.

Typically, every pol has a central courtyard, which lights up the portions behind the house. Beneath every house is a provision for underground water cisterns that fill up with harvested rainwater from rooftops. The courtyard also connects the different floors, so that each family gets ample ventilation and privacy. What’s remarkable is the strategy for windows. While the top floor of the three storey house, has a small aperture, like a jaali for ventilation, the middle one opens out not only for air but also for a view and to connect with neighbours, while the one closer to the street brings in light and cool air. As one goes higher, each floor vertically projects outward, affording shade to the floor below, and thus keeping the house climatically safe, both from the sun and rain. Many pols have now been converted into cottage industries for promoting textiles and craft. Others have been commercialised, turned into markets for utensils and other goods.

Musician Jagdip Mehta had spent his childhood in one such house in Moto Suthar Wado, an area famous for pols. With a loan from HUDCO, and help from the state government’s heritage conservation committee and the French government, he turned a 200-year-old house into a homestay. What started as a small project of getting toilets attached to bedrooms, turned into a full-fledged restoration, which has won awards for heritage conservation. “My father and I were born and brought up in the old city. Here it’s very quiet and because of the thick walls, and ground tanks, the temperatures are five to six degrees below normal in summer. Also we have our extended family living next door, what more do I ask for,” says Mehta, who has a steady stream of tourists visiting his heritage home regularly.

While it’s easy to fall into the gentrification trap, it could be the only way to save pol houses, most of which are contested properties held by multiple owners. Founder and director of House of MG, Abhay Mangaldas is probably the largest stakeholder in private heritage in the old city, with the Mangaldas haveli and a soon-to-be opened, six-room pol-turned-boutique hotel. “Tourism is the only route to save the fabric of the old city. With multiple owners in practically every pol, there is no question of one-size–fits-all answer. If the government can extend the special economic zone status to pol houses, declare it a precinct and turn it into an art and culture hub, it’s possible to revive them,” he says. “While political will might get us the Unesco Heritage City tag, keeping it will not be an easy task unless laws are enforced.”

Pandya too isn’t convinced about winning a heritage status. “The old city alone doesn’t make Ahmedabad qualify for the tag. Often heritage conservation is seen only from the visual aspect. What good is it if the wooden facade is retained but the house has been turned into a garage or a godown? Can we look at heritage not just as a document or paper?” says Pandya.