Ahmedabad

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The name of the city

A

Ritu Sharma, April 22, 2023: The Indian Express

While several cities in India changed their names like Gurgaon became Gurugram, Allahabad is now Prayagraj, Hoshangabad is Narmadapuram, and more recently Aurangabad was renamed Sambhajinagar, Osmanabad to Dharashiv and Daulatabad to Devgiri, the struggle for Ahmedabad in Gujarat to be renamed Karnavati continues even after more than three decades since the political parties started debating over it. The first serious attempts to rename the city started after Bombay was renamed Mumbai when the Shiv Sena came to power in Maharashtra in 1995.

It was after the BJP came to power in the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation in 1995, that the movement for renaming the city to Karnavati, a name used till date by the R S S, its affiliated arms and the BJP, for the city, gained momentum.

While efforts by the ruling BJP that started the demand and campaign for the name change of Ahmedabad to Karnavati might have weakened, it is the R S S-backed student body Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) that continues to press for this name change.

During the annual congregation of the ABVP on February 27 in Ahmedabad, a day after the city’s official foundation day, three resolutions were passed – one being the name change of Ahmedabad to Karnavati.

ABVP city secretary Umang Mojitra told The Indian Express, “Since the foundation of ABVP in 1960 in Gujarat we have been using Karnavati and continue to do this till Ahmedabad is officially changed to Karnavati. As soon as the exams get over, we have planned to take this demand forward to the city authorities and district collector.”

The resolution reads, “On Rishi Dadhichi’s land of penance which is beside river Shvabhravati it was King Karnadev who established this city that has today shaped into a mega city… which is a proud moment for all of us.”

“The city set up in the 11th century has witnessed a lot of ups and downs but in the medieval time the Mughal invaders tried a lot to wipe out city’s presence and our culture. One of the attempts of which was the legend made popular – jab kutte par sassa aya Badshah ne shahar basaya (Impressed by a hare chasing a dog, Sultan Ahmed Shah who was in search of a place to build his new capital, decided to locate his capital on the bank of River Sabarmati and called it Ahmedabad).

“The proof of existence of Karnavati can be clearly seen in the scriptures of Jain saint Prabodh Chintamani in the 12th century. Karnavati was established in the 11th century which is proved by several evidence…” the ABVP said, justifying its demand.

In the book, ‘Architecture at Ahmedabad, The Capital of Goozerat’, Theodore C Hope, an officer of the Bombay Civil Service, and British architect James Fergusson wrote in 1866: “Modern investigation has not yet proceeded sufficiently far to enable it to be stated with certainty how far Kurunawutee (Karnavati) was contiguous to or identical with Ashawul (Ashaval) and Shreenuggur (the way Jains referred to Ahmedabad), both of which names occur in early records as those of a great city hereabouts, but there can be no doubt that the new town of Ahmed Shah to which he gave his name Ahmedabad and its suburbs, embraced them all.”

The writers note that when Ahmed Shah wanted to shift his seat of power from Anhilvad Patan to the banks of the Sabarmati, it was to “Kurunawuttee (Karnavati)” founded by the Solanki rulers three hundred years before 1411.

‘Ahmedabad: The Millennial Heritage City’ by GM Hiragar, a former Gujarat information officer and former in-charge director at the Sanskar Kendra City museum, compiles the various names of Ahmedabad as various travellers recorded it.

Duarte Barbosa, a Portuguese explorer, had called the city Andavat. Sir Thomas Roe, a British diplomat who visited India between 1614 and 1644, had called it Amdavaz. William Hawkins, a representative of the East India Company, had called it Amdawar; William Finch, a merchant with the East India Company who travelled with Hawkins to India during Emperor Jahangir’s reign, had called it Amdaver.

The epic Heersaubhagyakavya, written during Jahangir’s time, calls Ahmedabad, Ahammadavad and describes it as the “beautiful face of Gurjar Laxmi” and Patan and Khambhat as her earrings. Locals then simplified it to Amdavad. Maganlal Vakhatchand Sheth who wrote the first history of the city in Gujarati in 1850 AD titled it “Amdavad no itihas”, a name that locals continue to call the city by.

Ratnamanirao Bhimrao Jhote in his work “Gujarat nun Patnagar Amadavad” explains the meaning of ‘Amad’ as ‘without arrogance or vain’. The Mirat e Ahmadi notes the foundation day of Ahmedabad as February 27 while the Ahmedabad Gazetteer notes it as March 4, 1411. Hiragar’s book cites eminent historian Hariprasad Shastri determining the date of the foundation of Ahmedabad as February 26, 1411, based on vastu shastra.

History

The Indian Express, February 21, 2016

The city that Ahmed Shah built

Written by Shiny Varghese

Kites, hundreds of them, like memories, float and stick out in corners of the old city. They are everywhere — on tree tops, on towers, on cables. Lal Darwaza is the entry to the walled city of Ahmedabad, spanning centuries of history. On one side of the road is a colonial bungalow-turned-boutique hotel, House of MG, dating from 1924. Just opposite is the iconic Sidi Sayed Mosque, a prelude to all that the old city holds. Built in 1573, by a slave of Ahmed Shah I (after whom the city is named), the mosque is a visiting card for the city itself. You could pass it by and not realise what the fuss is about, until you arrive at the entrance, and see the intricate stone jaalis. Through the geometric squares in arched windows, slivers of the blue sky and green trees light up the dark interiors of the mosque. The “tree of life” lattice here has been used for the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Ahmedabad logo, and can be seen on many tourism brochures and advertisements.

We are at the tumultuous bazaar in the precinct of Bhadra, the fort in the old city. It was here that Ahmed Shah laid the foundation of Ahmedabad in AD 1411. Some of the most prominent structures in the precinct belong to his reign, like the Jami Mosque and Raja-Rani no Haziro (King and Queen’s tomb). On the edge of the central square is BV Doshi’s Prembhai Hall. British architect Claude Bately’s Electricity House, with its European plan and Indian elements of chajjas and jaalis, is located just before the entry to the citadel area.

“You will see flavours of different kinds in the old city,” says Ahmedabad-based architect Yatin Pandya, “It has maintained its own character, melding cultures and styles seamlessly, from the Gujarat Sultanate to the Mughals and the British.”

A group of architects and designers were on a trip to Gujarat last month, organised by the Indian Institute of Interior Designers, Delhi chapter. Pandya was our guide, anthropologist and social interpreter. He has mapped the city in his head and on paper, covering its cultural, architectural, and historical heritage. Now that it has been chosen as a contender for the Unesco Heritage City tag, they were here to assess its worthiness.

For one, the city was probably the first to have an underground drainage and water supply system, a century before urban planners came on the scene. President of the Ahmedabad municipality in 1885, and founder of the first textile mill, Rao Bahadur Ranchhodlal Chhotalal was instrumental in this futuristic move, which still serves the city more than 106 years later.

The famed pol houses of the city have been selected for their historic character, environmentally sustainable architecture, and for being socially interactive spaces.

To reach the pols, one enters through the braided streets of Dhalgarwad, the stretch from Bhadra to Manek Chowk, a historic market in the city, where a riot of colours and heady aromas hit the senses. In Manek Chowk we see an example of the morphing of space that the city is known for. The traders feed cattle every morning before they begin business to attract good luck. After which, the area expands into a parking lot, and at night when the cars vacate their spots, the space is taken up by vendors of street food.

This optimal use of space stretches into the pols too. Pol comes from the Sanskrit word pratoli, which means gateway or entrance. It was built by groups of families based on occupation, or kinskip and clan, or ethnicity. “It was not based on economic differences. So a mill owner and a worker would possibly stay in the same pol, creating mutual interdependence and respect,” says Pandya, as we arrive at Haribhakti ni Haveli.

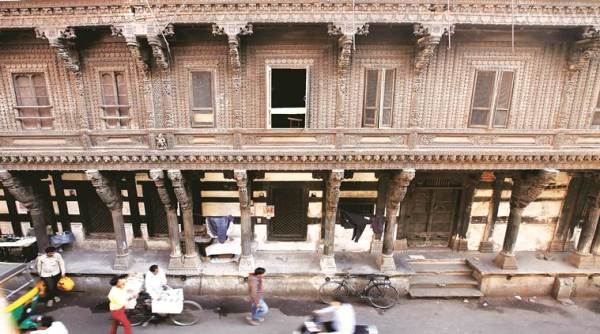

As if someone has turned down the volume, it’s quieter, cleaner and strangely not congested even though the row houses stick to one another and maintain their proximity to the street. With tiny entrances, this pol house has a wooden facade, with columns, brackets and railing details carved intricately. “Various sets of carpenters would have done numerous jharokhas, doors and window panellings, and could make my house different from yours,” Pandya says, pointing to the panels.

Typically, every pol has a central courtyard, which lights up the portions behind the house. Beneath every house is a provision for underground water cisterns that fill up with harvested rainwater from rooftops. The courtyard also connects the different floors, so that each family gets ample ventilation and privacy. What’s remarkable is the strategy for windows. While the top floor of the three storey house, has a small aperture, like a jaali for ventilation, the middle one opens out not only for air but also for a view and to connect with neighbours, while the one closer to the street brings in light and cool air. As one goes higher, each floor vertically projects outward, affording shade to the floor below, and thus keeping the house climatically safe, both from the sun and rain. Many pols have now been converted into cottage industries for promoting textiles and craft. Others have been commercialised, turned into markets for utensils and other goods.

Musician Jagdip Mehta had spent his childhood in one such house in Moto Suthar Wado, an area famous for pols. With a loan from HUDCO, and help from the state government’s heritage conservation committee and the French government, he turned a 200-year-old house into a homestay. What started as a small project of getting toilets attached to bedrooms, turned into a full-fledged restoration, which has won awards for heritage conservation. “My father and I were born and brought up in the old city. Here it’s very quiet and because of the thick walls, and ground tanks, the temperatures are five to six degrees below normal in summer. Also we have our extended family living next door, what more do I ask for,” says Mehta, who has a steady stream of tourists visiting his heritage home regularly.

While it’s easy to fall into the gentrification trap, it could be the only way to save pol houses, most of which are contested properties held by multiple owners. Founder and director of House of MG, Abhay Mangaldas is probably the largest stakeholder in private heritage in the old city, with the Mangaldas haveli and a soon-to-be opened, six-room pol-turned-boutique hotel. “Tourism is the only route to save the fabric of the old city. With multiple owners in practically every pol, there is no question of one-size–fits-all answer. If the government can extend the special economic zone status to pol houses, declare it a precinct and turn it into an art and culture hub, it’s possible to revive them,” he says. “While political will might get us the Unesco Heritage City tag, keeping it will not be an easy task unless laws are enforced.”

Pandya too isn’t convinced about winning a heritage status. “The old city alone doesn’t make Ahmedabad qualify for the tag. Often heritage conservation is seen only from the visual aspect. What good is it if the wooden facade is retained but the house has been turned into a garage or a godown? Can we look at heritage not just as a document or paper?” says Pandya.

Heritage monuments

2017-19: several treasures “compromised” or “demolished”

From: Paul John, July 19, 2019: The Times of India

From: Paul John, July 19, 2019: The Times of India

Two years after Ahmedabad’s Walled City was declared a Unesco World Heritage City, several of the architectural treasures that helped it bag a place on this hallowed list have been found either “compromised” or “completely demolished”.

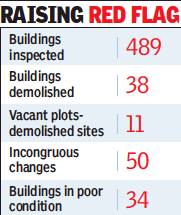

Of the 489 listed properties the heritage department had set out to validate, 11 are now “vacant plots” and as many as 38 buildings have been demolished. The inspection team found 50 instances of modern structures being incorporated into heritage buildings. They also recorded 34 poorly maintained buildings. Overall, 30% of the heritage properties surveyed were listed as “compromised” or “vulnerable”.

The Amdavad Municipal Corporation (AMC) is inspecting 1,700 more listed structures and the number of missing or demolished heritage properties could rise, sources said. Civic officials had flagged the issue during a February 27 meeting of the Heritage Conservation Committee (HCC), an independent body that oversees conservation initiatives. The initial estimate was that 10% of the listed properties in the Walled City had suffered extensive damage or were completely destroyed.

Town Development Officer (TDO) central zone Ramesh Desai said that in many instances, people are not aware that their properties have been listed as world heritage. Desai said that in case of vacant plots, where the heritage structure has been completely demolished, legal restoration becomes extremely difficult in the absence of old building plan records and non-availability of documents.

There are 2,236 listed residential properties and 449 institution buildings in the walled city precinct inscribed as World Heritage City. After the first phase of checking 489 properties, the HCC has directed that a combined team of the AMC’s heritage department and the Ahmedabad World Heritage City (AWHC) trust continue with a site inspection of remaining 1,700-odd properties to get a clear picture for an accurate ground report.

Subsidence

Ahmedabad sinking by 25mm/year: Study, 2021

TNN, January 9, 2023: The Times of India

From: TNN, January 9, 2023: The Times of India

AHMEDABAD: The sinking town of Joshimath in Uttarakhand is an eye-opener to the dangers of land subsidence and what it could do to towns and cities. Two years ago, a similar study was conducted for Ahmedabad city which is being continuously monitored by experts at Institute of Seismological Research (ISR).

They have found that land subsidence, a maximum up to the level of 25mm/year, was noticed in the southeastern and western parts of the city. Land subsidence is a gradual settling or sudden sinking of the earth's surface due to removal or displacement of subsurface earth materials.

Land subsidence (LS) of 20-25 mm/year was seen in Ghodasar, Vatva and Hathijan areas of the city. A second patch near the Ghuma and Bopal area, in western Ahmedabad, has also recorded annual subsidence of 15-22mm.

The study revealed that some additional patches of subsidence, with a rate of 2mm to 8 mm/year, was also noticed in central-west and central-east areas of Ahmedabad.

"The rate of subsidence is the same according to our study. Large scale groundwater extraction leads to vertical compression of aquifer sediments due to reduced pore pressure, and soil compaction.

This in turn results in land subsidence. Land sinking promotes micro-level topographic changes, cracks and fissures in the surface, ultimately causing heavy damage to the infrastructure," claim ISR researchers Rakesh Dumka, Sandip Prajapati and D Suribabu.

Scientists have appealed for greater public participation to arrest this phenomenon, including implementation of groundwater recharge in town planning schemes and its insistence in municipal governance.

"The high subsidence zone comprises the southeast and western parts of the city. The moderate subsidence zone comprises east-central areas, while the low subsidence zone comprises the central part of the city," observed Dumka. The study also notes that ground subsidence due to groundwater depletion has already been reported in Gandhinagar in 2018.

The scientists had relied on groundwater level data from the central groundwater board between 1996 and 2020. They painstakingly used Sentinel satellite's Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar data between 2017 and 2020, which measures ground deformation with sub-centimetre level accuracy, and the latest global navigation satellite system-based precise technique to measure land subsidence.

Traffic

Yellow junction-boxes/ 2023

Sahil Kukreja, July 17, 2023: The Times of India

Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) has painted a unique yellow box with criss-cross lines at a junction in Panjarapol, in a bid to combat traffic congestion and make traffic flow smoother. As a part of the movement, AMC plans to create such yellow boxes at 25 different junctions in the city, with this being the first.

The yellow Junction Boxis designed to prevent gridlock at junctions.One must not enter the yellow box unless the exit is clear i.e. there is space on the opposite side of the junction for your vehicle to cross the box completely without stopping. However, there is one exception. If a vehicle owner wants to make a turn, they can enter the box and wait until the path is clear of traffic. Waiting in the Junction Box until your respective exit is clear is legal.

"These yellow boxes are usually placed at junctions that experience high traffic congestion, as well as near fire or ambulance stations where emergency vehicle movements are frequent. The purpose of these boxes is to keep the junction clear for through-traffic, thus preventing traffic jams," said a senior civic official.

The official also warned, "Citizens should not simply follow the vehicle in front as it may stop and prevent your exit. You should also not let other drivers pressure you to enter the box when a clear exit is not available. This could invite a heavy fine."

AMC plans to implement a fine structure for violators of the yellow box rule in the coming months. Offenders will be fined similar amounts to those imposed for crossing the stop line or jumping a traffic light. To enforce this rule, the AMC and the city traffic police are training artificial intelligence programs installed in CCTV cameras to capture the registration numbers of vehicles that violate the yellow box rule.

Do you think the introduction of the new yellow Junction Box help traffic flow smoother? Let us know in the comments down below.

Walking tour of city

Trek through India’s only WORLD HERITAGE CITY, February 24, 2018: The Times of India

Unlike most old cities in India, Ahmedabad’s Walled City is defined by its living heritage which embraces within its precincts a unique visual grammar. Everything is within sniffing distance. A muezzin will give the call for namaz a stone’s throw from a Jain or a Hindu temple. A synagogue will stand shoulder-to-shoulder with a Parsi fire temple. Cloth and utensil merchants shout above the din of traffic even as residents of the city’s more than 600 pols (traditional self-contained micro-neighbourhoods), enjoy quietude next door.

Ahmedabad is not only India’s first Unesco World Heritage City, it also provides an insight into a city with continuous urban habitation for many centuries, much like Cairo, Rome, Paris, Vienna, Rome and Edinburgh.

Here is your chance to go behind the lens and get a panorama of the unique, 600-year-old Amdavadi culture, on the Times Ahmedabad Heritage and Architectural Photography Passion Trail, conducted in collaboration with Gujarat Tourism. Take in the grand Burma teak façades of more than 2,696 havelis with their underground water tanks, some of which could be two centuries old. Intricate motifs, jharokhas, pearl-drop shade borders and sandstone tracery in Islamic monuments showcase tolerant social values.

The Islamic architecture of the city, called the Gujarat style, is a curious mixture of Saracenic (Arabic) and Indian architectures, and is not found anywhere else in the country. Our award-winning heritage expert, Debashish Nayak, will take you on a unique herita g e walk designed by him. On the first day of the trail, called ‘Mandir se Masjid’, which is also India’s first, you will be introduced to the culture of a close-knit pol community, an interactive neighbourhood, covering 20 main spots. The same day, you will visit a unique utensils museum, Vechar, at Vishala.

On the second day of the trail, you will have a chance to visit mosques, rozas, and darwazas, which played a pivotal role in earning the city its coveted Unesco World Heritage City status in July 2017.

Nayak says, “Our ancestors had developed a taste for visual grammar. They have set for us a perfect example of the optimum use of space, eco-friendly lifestyles and rainwater harvesting.”

He adds, “Photography allows you to capture the essence of a city by helping you blend the tangible and the intangible, thus allowing a peep into the city’s soul.”