Encephalitis: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Deaths due to Encephalitis

2014

Encephalitis claims 1,495 lives in 2014

Dec 23 2014

The Centre admitted that efforts to control encephalitis had not been able to contain the high death toll even as BJP members in the Lok Sabha accused the state government of indifference.

In his calling attention motion in the Lok Sabha, BJP MP Yogi Adityanath pointed out that more children have died of encephalitis in a year than in the terrorist attack on the Peshawar school recently .About 1,495 people, mostly children, have died so far this year.

To increase efficacy of its drive against `brain fever', which has been rather severe in parts of eastern UP and Bihar, health minister J P Nadda said the Centre will also involve MPs, MLAs and local bodies. “Despite our policies and funding, results which should have come are not coming. We are alive to the sentiments expressed by members and committed to deal with the disease.“

Bihar

How encephalitis stalked Bihar

June 22, 2019: The Times of India

From: June 22, 2019: The Times of India

From: June 22, 2019: The Times of India

From: June 22, 2019: The Times of India

See graphics:

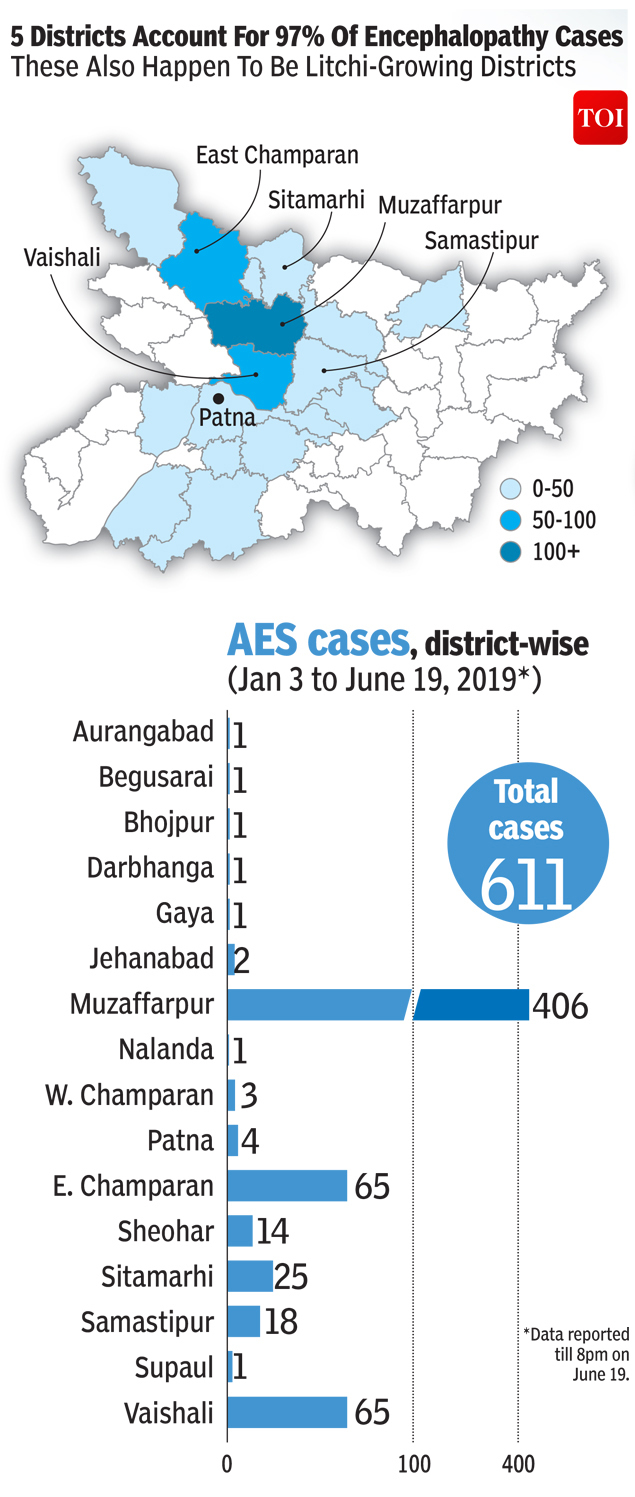

AES cases, district-wise, January 3- June 19, 2019

AES deaths, district-wise, January 3- June 19, 2019

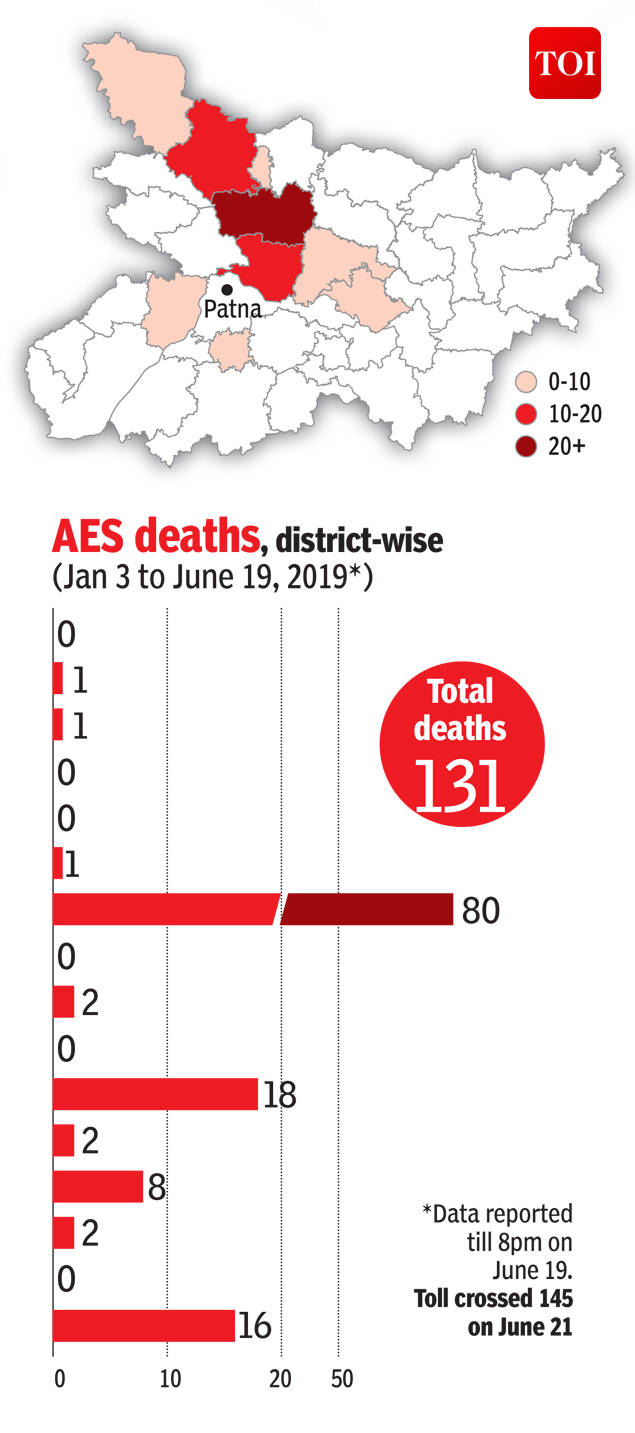

AES cases and deaths, age-wise

Muzaffarpur

2009-19

From: Piyush Tripathi & Ajay Kumar Pandey, June 18, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

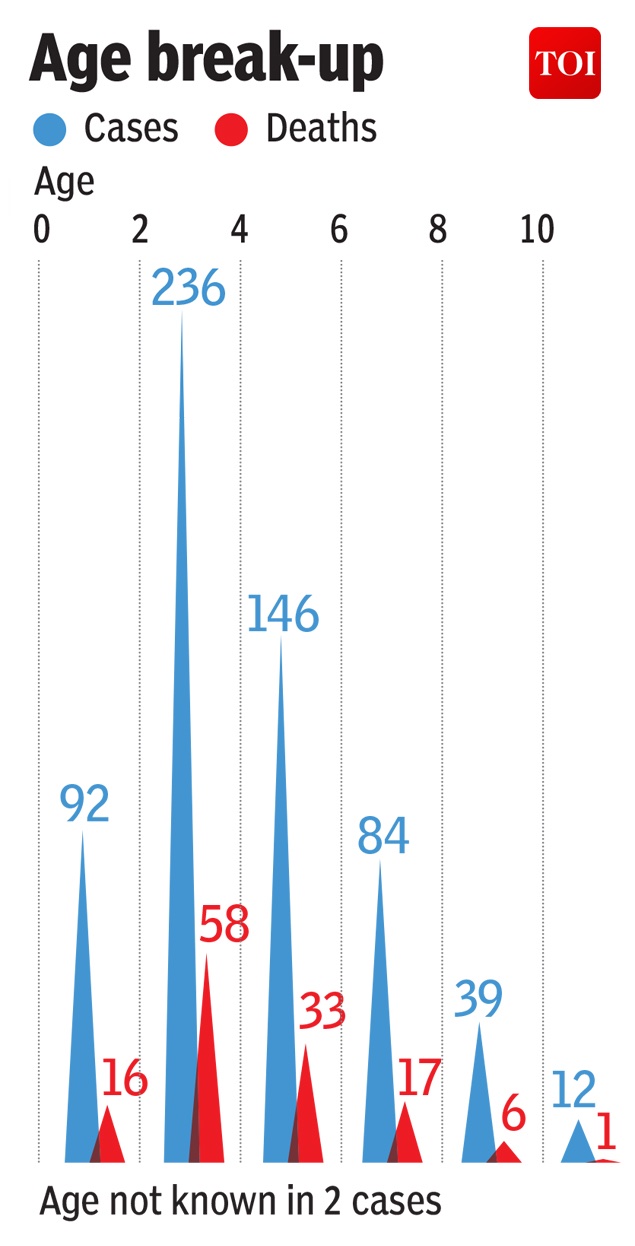

The death toll from Encephalitis in Muzaffarpur, 2009-19

Uttar Pradesh

2017> 18: a success story

Sushmi Dey, June 23, 2019: The Times of India

While Bihar struggles to contain acute encephalitis syndrome, the eastern part of neighbouring Uttar Pradesh, which has also been a problem area, has seen a significant improvement with an over 67% drop in deaths due to the disease in 14 most-affected districts.

Japanese encephalitis and acute encephalitis syndrome were major health challenges in eastern UP and poor health infrastructure proved to a serious handicap for the Yogi Adityanath government in 2017 when a spate of child deaths — not all related to the disease — rocked BRD medical college in August, 2017.

More than 500 children died that year in Gorakhpur and its neighbourhood with as many as 14 districts of the region in the grip of encephalitis. The state government launched Action Plan 2018 with a multi-pronged approach in collaboration with the WHO and Unicef to tackle the encephalitis menace.

In 2018, deaths due to AES dropped to 166 from 511 in 2017. The number of encephalitis cases reported in 14 districts of eastern UP also dropped from 2,247 in 2,017 to 1,047 cases last year. In 2019 so far, 20 deaths have been recorded from 82 cases, according to UP government data. “The government worked on a plan and the results are for everyone to see,” says K K Gupta, director general of medical education and training in UP government. He said several measures included intensive vaccination and sanitation campaigns, improvements in health infrastructure and health resources (addition in beds and creation of more positions of nurses and paramedics apart from doctors.

Public health experts working in the region say Uttar Pradesh laid a lot of emphasis on early diagnosis and providing immediate care. In 2017, the UP government started a campaign against the disease involving multiple stakeholders. As a result, the outbreak of disease itself has decreased considerably in the last two years.

Socio-economic profile of the affected

Bihar, 2019

Rema Nagarajan, June 24, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, June 24, 2019: The Times of India

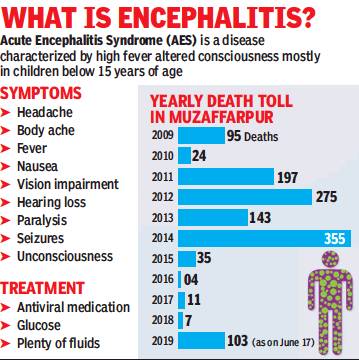

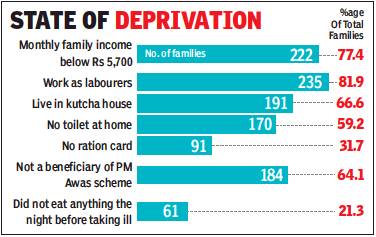

A social audit of families of children admitted with acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) conducted by the Bihar government reveals just how poor they are. More than three-fourths of those surveyed would fall below the poverty line (BPL). The audit data accessed by TOI is for 287 of the families of children with AES reported till now.

The average annual household income of the families surveyed was a little over Rs 53,500 or about Rs 4,465 per month. The Rangarajan Committee had defined the poverty line in rural Bihar in 2011-2012 as a per capita monthly income of Rs 971. For an average family of five persons, this works out to Rs 4,855 per month. Even adding a very modest 2% annual inflation for the eight years since then would take that figure to Rs 1,138 today or about Rs 5,700 for a family of five people.

Over 77% of the families surveyed earned less than this and a large number of them had 6-9 family members or more. There were families that reported an annual income of as little as Rs 10,000 and the most well-off among those covered by the audit had an annual income of under Rs 1.6 lakh. Approximately 82% (235) of the households surveyed earned a living by working as labourers.

AES OUTBREAK

Audit: In 3/4th of cases, elders unaware of AES, PHC treatment

About a third of the families had no ration card and about a sixth of those who did have one had not received any rations the previous month. In 200 of the 287 cases surveyed (about 70%), the families said their children had played outside in the sun before being taken ill with AES. And 61 of the children had eaten nothing the night before they fell sick.

Roughly two-thirds of the families, 191, live in kutcha houses. Yet, only 102 had benefitted from the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. Though 87% had access to drinking water, almost 60% did not have a toilet. Though the government claims to have provided ambulance services, 84% of the families did not use the service for taking the children to the hospital and in almost all these cases, they were not aware of it.

About 64% of the households were from areas surrounding litchi orchards and a similar proportion said the child who fell ill had eaten litchi. Surprisingly, in threefourths of the cases, the elders were not aware of chamki bukhar or AES nor were they aware that treatment for it was available at the primary health centre (PHC).

Only a quarter of the cases were referred to the primary health centre for treatment. This is not surprising, as in most AES cases, the symptoms surface in the early hours when most primary health centres are closed apart from the fact that many of them are severely understaffed.