Wular Lake

Ghumakkar

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The lake

Nishat Tours and Travels

Coordinates : 34°20′N 74°36′E

Primary Inflows : Jhelum

Surface area : 12 to 100 sq mi (30 to 260 km²)

Island : Zaina lank

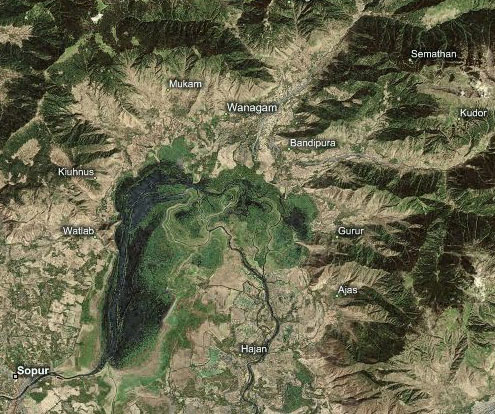

Settlements : Bandipora

This is one of Asia's largest fresh water lakes. It changes character with every few miles. The drive from Srinagar will take you to the calm waters of Manasbal , where there is no other sound but birdsong. Manasbal has often been described as the bird watcher's paradise, and as your shikara glides through this mirror of tranquillity, you will experience yet another facet of Kashmir.From Watlab, the Wular Lake stretches away as far as the eye can see, edged by picturesque villages around terraced breeze-rippled fields of paddy, in a riotous burst of colour, the sheer grandeur of the spectacular countryside at leisure.

Wular Lake is the largest freshwater lake in India and lies in the Kashmir Valley, 40 km northwest of Srinagar City in the Northwest of India. With a size of 189 sq. km, Wular Lake is also one of the largest freshwater lakes in Asia. The lake lies at an altitude of 1,580 m. Its maximum depth is 14 metres, it has a length of 16 km and a breadth of 10 km.

Wular Lake plays a significant role in the hydrographic system of the Kashmir Valley by acting as huge absorption basin for annual floodwater. The lake and its surrounding extensive marshes have an important natural wildlife. The rivers Bohnar, Madamati and Erin from the mountain ranges and the rivers Vetasta (Jhelum) and the Ningal from the south bring hundreds of tons of silt into the lake every year. This rampant siltation and the human encroachments have devastating effects on the lake.

The old Wular

Can mistake that ruined majestic Kashmir lake be fixed? AP (Associated Press)| Nov 13, 2016

The name Wular itself means "stormy" in the local Kashmiri language, and once described the lake's strong winds and choppy waters. Formed within a deep cavern created by ancient earthquakes, the lake was for centuries considered a paradise by writers, philosophers, nobles and travelers who camped on its banks and reveled in legends of an ancient city that vanished in the 5th century when a massive flood filled in the lake.

Associated Press

Mohammed Azim Tuman remembers a boyhood spent steering his houseboat by moonlight over towering waves.

"My heart would be racing as I clung to the railing to keep from falling into the water," said Tuman, the elderly proprietor of a tourism business. "When a storm hit, the water would splash so high I thought, 'My god, the boat will be swallowed whole.'"

Back then, Kashmir was still a sleepy principality at the edge of the British Empire.

Wular's surface lies flat, lifeless and in some spots stagnant, teeming with mosquitoes. The water trickles in from the Jhelum River, and meanders some 16 kilometers (10 miles) before emptying through a dam on its way toward Pakistan.

How the Wular started shrinking

Early 1900s: Flood protection works gone wrong

Reana Thomas, Kashmir: The Decline of Wular Lake, September 2, 2014, Pulitzer Center

The rapidly disappearing beauty of Wular as seen from a boat in the northern portion of the lake. As invasive plant species, pollution, and silt continue to enter the lake, this sight may become a rarity.. Add this image to a lesson

The mountainous roads near the town of Bandipora surround what looks like a huge meadow. A closer look reveals that the meadow is actually the water of Wular Lake hidden by floating vegetation, agricultural plots, and intentionally planted trees.

Associated Press

Even from the Wular Vantage Point, which provides visitors with a panoramic view of the northern side of the lake, many people often wonder where the actual lake is since a majority of it looks green. What used to be open water is now covered by rice paddies and thousands of willow trees that were planted by the government during the 1980s as a source of firewood.

Human intervention has caused much of the degradation with the problems stemming from multiple sources. Numerous issues stand in the way of Wular Lake’s survival, and thus the survival of the people who fully depend on it.

People are losing their livelihoods because the lake management authorities are not doing enough to conserve the lake. On the other hand, as globalized markets reach their villages, the residents are polluting the lakes with chemicals, such as dishwashing liquids, soaps, cleaning solutions, and fertilizers.

Hydrological systems in Kashmir were tampered with long before the 1947 when maharajas ruled the lands. Ajaz Rasool, an experienced hydrological engineer, told the story of one Kashmiri maharaja in the early 1900s:

The king’s constituents living around Wular Lake faced severe flooding year after year. The lake was a sponge that retained large amounts of water from the glacial streams flowing down the surrounding Pir Panjal range of the Himalaya mountains. The flooding damaged the crops and homes of the people. The ruler decided to alter the water levels of the lake with the help of British engineers. This was done without much heed to the potential disruption it would cause to the environment.

The people were saved from the flooding, but now, over 100 years later, the whole system has completely reversed. Extremely low water levels are a cause for concern. The lake basin is not able to hold water due to siltation from deforestation and pollution, so it nearly dries up in July and refills during the winter. The lake is shallow, with a maximum depth of about 15 feet, and highly eutrophic, or rich in nutrients. The aggregate of these conditions makes a great environment for invasive aquatic weeds but an oxygen-poor system for fish and other animals.

Size in 1911, 2008

Can mistake that ruined majestic Kashmir lake be fixed? AP (Associated Press)| Nov 13, 2016

The surface and its surrounding marshlands have shrunk from 216 square kilometers (83 square miles) in 1911 to just 104 square kilometers (40 square miles) in 2008. Along the fringes, impoverished communities tend rice paddies and in autumn harvest wild water chestnuts from the lake shallows. The ornately carved wooden houseboats that once surfed Wular's waves are gone.

Wular's degraded state has not only ruined its prospects for tourism, but also has compromised the lake's function in absorbing heavy snow and ice melt from the mountains.

Aford

In 2014, Kashmir's main city of Srinagar, just 34 kilometers (21 miles) southeast of the lake, was inundated with floodwaters that wreaked billions of dollars in damage. It happened again a few months later in 2015, raising calls for renewed efforts to restore the region's natural water systems.

The earth is experiencing tremor after tremor,

The warnings of Nature are but too clear.

Khidr [Khizr], standing by Wular, is thinking:

When will the Himalayan springs burst?

— Urdu poet Dr. Mohammed Iqbal (1877-1938)

Wular's story is a familiar one — a story of development at nature's expense, of good intentions and profound regret, of wetlands disappearing.

1950s: Water-sucking willows planted

Can mistake that ruined majestic Kashmir lake be fixed? AP (Associated Press)| Nov 13, 2016

Long an inspiration to poets, beloved by kings, Wular Lake has been reduced in places to a fetid and stinking swamp.

Just the sight of it makes Mohammed Subhan Dar feel sick. He admits he's partly responsible.

Dar was among dozens of villagers employed in the 1950s by the regional government to plant millions of water-sucking willows in the crystalline lake. The goal had been to create vast plantations for growing firewood and timber for construction and cricket bats. The result was the accidental near-destruction of the lake, as the trees drank from its waters and their tangled roots captured soil and built up the land.

The lake, now less than half of its former capacity, no longer churns and heaves with high waves, but meanders across mossy swamps and trash-strewn backwaters. Children long ago stopped playing in the water. Families no longer use it to cook.

Associated Press

"It used to be so beautiful, so clear you could see the bottom. That glory is gone," said Dar, whose family has lived lakeside for seven generations. He alone planted at least a hectare (2 acres) of what is now a full-blown willow forest.

As Wular lost its appeal, its value declined. Poverty rates in the 31 surrounding villages shot up to around 50 per cent — five times the state average.

The authorities "did not realize what they were trading. They were so focused on protecting and growing the forest they lost sight of the lake," said Rahul Kaul of the nonprofit Wildlife Trust of India , which last year worked on an economic assessment of Wular's repair.

Kashmir and New Delhi officials now want to fell millions of trees, remove acres (hectares) of soil and dredge enormous patches of lake bottom. Proposals have been drafted, experts consulted and money pledged, including nearly $1 million already spent tearing up willow forest on the lake's eastern flank.

But restoring an enormous alpine lake is no simple thing, especially with climate change now threatening the Himalayan glaciers that feed Wular's waters, and deforestation still unleashing soil to clog it up once more.

Restoring such a lake in Kashmir — where a decadeslong violent conflict often supersedes all other government plans — may be near impossible.

Wular Lake is still in floods,

The North Wind howling strong;

The shore is far away, and you

Must steer your course with care.

— Kashmiri poet Mahjoor (1885-1952)

Encroachments, pollution

Reana Thomas, Kashmir: The Decline of Wular Lake, September 2, 2014, Pulitzer Center

When agricultural communities downstream ran out of water, they encroached on the lake itself and converted marsh areas into rice paddy fields. Wular Lake, one of India’s largest freshwater lakes that once claimed an area of 217.8 sq. km in 1911, has been reduced to about 80 sq. km today, with only 24 sq. km of open water remaining.

Aford

“Overall, the fish population [in Wular] has severely declined because of the human activity. It should be a self-cleaning system, but the pollution load is too much,” said Kundangar.

Chemical fertilizers, liquid and powder detergents, and human excrement all flow into the lake from the River Jhelum, which passes through the crowded city of Srinagar 40 km south of Wular, and also by the glacial streams that flow through smaller villages.

Wildlife

Birds

Global Nature . Nishat Tours and Travels

Wular Lake is a sustainable wintering site for a number of migratory waterfowl species such as Little Egzet (Egretta garzetta), Cattle Egzet (Bubulcus ibis), Shoveler (Anas clypeata), Common Pochard (Aythya farina) and Mallard. Birds like Marbled Teal (Marmaronetta angustirostris) and Pallas´s Fish-eagle (Haliaeetus leucoryphus) are species listened in the Red List of IUCN. Many terrestrial bird species observed around the lake are Short-toed Eagle (Circaetus gallicus), Little Cuckoo (Piaya minuta), European Hoopoe (Upupa epops), Monal Pheasant (Lophophorus impejanus) and Himalayan Pied Woodpecker (Dendrocopos himalayensis albescens).

Fish

Global Nature . Nishat Tours and Travels

Wular Lake is also an important habitat for fish and contributes about 60 percent of the fish yield of the Kashmir Valley. The dominant fish species found in the lake are: Cyprinus carpio, Barbus conchonius, Gambusia affinis, Nemacheilus sp., Crossocheilus latius, Schizothorax curvifrons, S. esocinus, S. planifrons, S. micropogon, S. longipinus and S. niger. More than 8,000 fishermen earn their livelihood from Wular Lake.

Reana Thomas, Kashmir: The Decline of Wular Lake, September 2, 2014, Pulitzer Center

Sixty percent of the fish produced for Jammu and Kashmir come from the lake area, but with fish populations declining, the fishermen are quickly losing their income. Poverty and marginalization affect more than half of the population living around Wular according to the Comprehensive Management Action Plan for Wular Lake (2007). Today, many fishermen have to search for alternative sources of income through manual labor or selling vegetables in the cities.

A middle-aged fisherman said that the fisheries try to work together now and pool their catch to split the profits among the settlements. During the off-season, they try to harvest water chestnuts, which grow quite abundantly in the lake. But, with invasive aquatic species, like alligator weed, blocking out sunlight and consuming nutrients, the beneficial vegetation may not survive. Dr. Ather Masoodi, an aquatic weed biologist, predicts that alligator weed has the potential to completely cover the lake in the next 10 to 15 years if weed management does not start immediately.

Associated Press

The Wular Conservation and Management Authority was only created in 2012 and has been slow to implement the proposed efforts to clear the water body of weeds, trees, and siltation.

Water-borne diseases result from the soiled waters since the surrounding settlements collect their drinking water from the lake.

Economic instability means that practicality often wins over preservation. People who live around the lake are not as concerned with the long-term outcomes for the environment if they are worry more about providing for their families. They are aware that the hydrological regime has shifted over the past couple decades and they foresee having to move into cities to find work.

“Sewage must be intercepted and treated, but this all needs a peaceful environment to work in,” said Rasool.

The global situation

Can mistake that ruined majestic Kashmir lake be fixed? AP (Associated Press)| Nov 13, 2016

Since 1990, the planet has lost 75 per cent of its wetlands as communities drained the water and built on the land. What's left today offers about $3.4 billion in services including water filtration, flood control and wildlife support, according to a 2010 report for The Economics of Ecosystems & Biodiversity , an ongoing project proposed by the Group of Eight industrialized nations to study monetary values for the environment.

Associated Press

More than half of that annual value in wetlands — or $1.8 billion — is delivered by wetlands in Asia.

"It's typical throughout India, not just in Kashmir. The critical balance between ecology and economy that is missed," said Anzar A. Khuroo, assistant professor of biodiversity at the University of Kashmir in Srinagar.

Kashmir's other losses include Anchar Lake, now almost entirely gone, and the famed Dal Lake in Srinagar.

Rectifying mistakes

Restoration plan

In recognition of its biological, hydrological and socio-economic values, the lake was included in 1986 as a Wetland of National Importance under the Wetlands Programme of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India for intensive conservation and management purposes. Subsequently in 1990, it was designated as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention. Nishat Tours and Travels

Can mistake that ruined majestic Kashmir lake be fixed? AP (Associated Press)| Nov 13, 2016

In 2008, Wetlands International came out with an $82 million plan to restore Wular's ecology. The costs would be recouped with 12 years from timber profits, improved fish stocks and an expected 40 per cent boom in ecotourism. Within 20 years, the report estimated, every $1 spent on restoration would lead to $2.74 in value returned.

The government was intrigued.

Experts confirmed there were profits to be made from a cleaner, healthier lake. Some suggested it could be done for a third of the cost.

Parliament in 2011 approved a budget of $26 million. Officials began talking about five-star hotels, riverside parks and boulevards for frolicking middle-class tourists and auctioning rights for running water sports.

If only it had been so easy.

How long will they remain hidden from the world,

The unique gems that Wular Lake holds in its depth.

— Urdu poet Dr. Mohammed Iqbal (1877-1938)

Getting everyone on board was a major effort. The willow plantations alone are carved into blocks controlled by individuals, villages and a multitude of state government bodies, while the lake's overall management involves even more departments including forestry, farming, fisheries, pollution control and the army.

It took years just to agree on the lake's boundaries. The project was again re-evaluated. The approved budget dropped to just $2 million.

By the time the first willows were chopped down, it was 2015. Only half the budget had been allocated, and those in charge of the work saw it wasn't enough.

Still, they chopped and dredged. They removed about a million cubic meters (1.3 million cubic yards) of silt — or 200,000 truckloads — before federal funding expired.

Project officials say the future felling of trees could bring in enough to reinvest $44 million in lake restoration. In the meantime, they want funding to restore 5 square kilometers (2 square miles) while they keep lobbying for more.

"What we've spent so far will be fatuous. It will have no impact at all," said Rashid Naqash, a government forest officer in charge of the program. "And then people will say it was a waste, declare it a failure and forget about it. But we can't give up."

Whether the project can survive is debatable. Any further work will need a new proposal, more evaluation, another environmental assessment, further debate and higher costs. Naqash said they'd need about $280 million more for the eventual goal of restoring 27 square kilometers (10 square miles).

That's many times more what has been spent so far.

Scientists warn that any efforts to repair Wular will be futile unless the plan also deals with areas far upstream, where lake-clogging soil and silts are still being loosed from newly deforested lands. The plan would also have to consider climate change, they say, which is upsetting Himalayan rainfall patterns and may affect how much water is available for the lake.

See also

Bio-diversity in Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh: Status Of Biodiversity In J&K

Bio-diversity in Jammu,Kashmir,Ladakh: An Introductions

Bio-diversity in Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh: Cultural and Historical Background