World War II and India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

World War II and the Indian Army

India Today, August 20, 2015

Battle cries and whispers

The Indian Army during the Second World War was at the time the largest volunteer army in history.

At the beginning of her exhaustive book, The Raj at War, Yasmin Khan says: "Britain did not fight the Second World War, the British Empire did." This is an important reminder despite the fact that, as Khan herself admits, it is no longer true to suggest that the imperial contribution to the war is a totally forgotten story. The centenary of the First World War, in which more than 1.5 million troops from undivided India took part, has only helped increase awareness, in both Britain and in India, about the ways in which the two World Wars were South Asia's as well. The Indian Army during the Second World War was at the time the largest volunteer army in history. Some 2.5 million Indians joined the war, at least 100,000 were killed or injured. The numbers are startling, but Khan's book aims to look beyond just the numbers of the military and economic contribution of the Raj to the war effort.

The Raj at War is more focused on telling history from the bottom up. The big figures-Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Subhas Chandra Bose-feature too, but high politics unfolds in the background as Khan focuses on what was happening at the ground level. Khan's focus is on understanding the underlying ways in which the war shaped the Indian subcontinent itself. In doing so she tells the story not just of the infantryman or officer of the Indian Army but also of the other men and women who propped up the Indian Army's war effort-the non-combatants, camp followers, lascars, prostitutes, nurses, refugees and peasants, to name just a few. But beyond those involved in the minutiae of war, the book also looks at those Indians away from the army who also experienced and were impacted by the war. These were merchants, industrialists, seamen, agriculturists, black marketeers, people in small towns and big cities, interned Europeans, American GIs-all of whom had to negotiate the war.

It is a lot of ground to cover and the book is dense with detail. If there is one criticism of the book, it is with the structure and layout of the chapters. The chapter headings give no clue of the details they contain and include no subheadings. If it's a criticism, it is only because the book contains a wealth of material that should be easier to reference. Despite this drawback, Khan's prose-crisp and clear-hugely aid the reader navigate the breadth of material she draws on for the book. In assessing the impact of the war, Khan starts with the military but also looks at how social and political changes were driven by the events and conditions of the war years. Army recruiters went into action as soon as the war was declared. It was not an uphill battle initially to get men to sign up with promises of regular food and wages. Middle-class Indians, unlike in the First World War, had the opportunity to fight as officers. The impact of this proximity with the British officer classes, the change in the composition of the army and slow-changing institutional and racial biases (it was only halfway through the war that Indian officers could sit on court martials of British soldiers) was to unfold over the course of the war and impact the future of the Indian state as well.

At the same time, the war economy boomed, providing opportunities for sections of the population-women especially-to now join the workforce. For India's businessmen, the war gave an opportunity to further their huge fortunes by providing military supplies. Khan writes: "Cities such as Karachi and Bangalore boomed, the infrastructure of airlines, companies and road networks were laid by wartime projects, and consumer imports from tinned food to fridges came onto the market? Middle-class women found new freedoms in work and activism. Nehru's planned economy and the welfare-orientated developmental state that he tried to craft after 1947 had its roots in the Raj's transformation of the 1940s." The intensity of action the Indian subcontinent saw during the war is somewhat forgotten today but it is worth remembering George Orwell's words in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbour: "With the Japanese army in the Indian Ocean and the German armies in the Middle East, India becomes the centre of the war." Even the tea plantations in the east of India were no longer remote, falling as they did squarely in the path of a Japanese advance. Khan describes how tea plantation workers were employed to build escape roads to the west in exacting weather conditions even though they had no experience of construction. Perhaps the worst outcome of the Japanese advance was the government policy in 1942 of destroying rice stocks and boats in coastal Bengal in advance of a possible invasion. On Winston Churchill's orders only those directly involved in the war effort were to be fed. The indifference marked the onset of the Bengal famine. Khan recounts how the victims displayed "hollow eyes in sockets, skin like paper. The dead and the dying were now sometimes indistinguishable". The famine was only another reminder of what had already become clear-British rule in India was no longer tenable. The Quit India movement had taken a shape of its own, even with most of the Congress top brass in prison. By the end of the war, as uncertainty over the country's future loomed, unrest spread. Demobilised soldiers began re-evaluating their allegiances. As one Indian sailor who mutinied in 1946 put it: "I was 22. I had come through a war unscathed-a war fought to end Nazi domination. I began to ask myself questions. What right had the British to rule over our country?" For the post-colonial South Asian states, the Second World War is often forgotten in the face of the landmarks of Independence and the trauma of Partition.

World War II in Northeast India

NEFA/ Arunachal Pradesh

Lost US aeroplanes

Prabin Kalita, Oct 30, 2023: The Times of India

Guwahati : A piece of scattered history about a monumental aerial feat will get a permanent address in “The Hump WWII Museum” that Arunachal Pradesh is preparing to unveil in East Siang district’s Pasighat, the oldest town of the state. This extraordinary museum is set to house the recovered remnants of the US aircraft that met their fate in the eastern Himalayas while valiantly flying supplies to the Chinese resistance fighting the Japanese during World War II. In 1942, after the Japanese blocked the 1,150km Burma Road, a mountain highway connecting Lashio in presentday Myanmar and Kunming in China, the US-led Allied Forces conducted one of the largest and longest-ever airlifts in aviation history, transporting nearly 6,50,000 tonnes of supplies, including fuel, food, and ammunition.

Allied aircraft flew a perilous 500-mile air route from airfields in Assam to Kunming, winding their way through the untamed terrain of Arunachal and Myanmar. The pilots dubbed this challenging route “The Hump” because their aircraft had to navigate deep gorges and then quickly ascend over mountains rising beyond 10,000 feet.

Between April 1942 and August 1945, more than 1,600 airmen and about 650 transport planes disappeared into the daunting mountains and forests on either side of the Hump — swallowed by the unforgiving landscape and extreme flying conditions.

Even today, the mountains of Arunachal often experience unpredictable weather, sudden heavy winds, and zero visibility within seconds, making flying a formidable challenge.

The museum project is being spearheaded by CM Pema Khandu, and the state govern ment intends to invite the US ambassador to India for its official inauguration. “The museum’s name pays tribute to the Hump operation, one of the most remarkable feats of aviation history during the Second World War. The museum is nearing completion and will be inaugurated soon,” Khandu tweeted, sharing updates on its progress. US investigators have been conducting search missions in India to find remains of American personnel missing since WW-II. The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) has been persistent in its quest, deploying teams to the remote regions of northeastern India. The 2017 mission was their fifth to India since 2013.There are approximately 400 US airmen missing in India, most of whose remains are believed to be located in the mountains of the Northeast.

The battles of Imphal and Kohima: Britain's greatest?

Britain says its greatest battle was fought in Imphal and Kohima

Alok Pandey and B Sunzu | May 28, 2013

By the time the war ended, it was one of the most brutal campaigns in military history. For the British, the war may have ended in victory, but the empire was never the same again. The end of the Raj was near. For Japan, the loss of South Asia marked the end of its era of aggression, the end of its imperialist ambitions.

The decisive battles of Imphal and Kohima during World War II have been voted the greatest battles fought in the history of the British Army in a contest organised last month by the National Army Museum in England.

For amateur war researcher Rajeshwar Yumnam and his team, the bad weather and threats from extremists were hardly a deterrent, as they relentlessly dug around a hilltop in Manipur's Sadar Hills district, which served as a Japanese army post during World War II

For Mr Yumnam and his team, the place was a potential goldmine, with their metal detector beeping almost everywhere in Motbung, one of the areas that saw a do-or-die battle between Japanese troops and British soldiers in 1944, during the war. A defeat here at the hands of the British troops had forced the Japanese to eventually surrender in a theatre.

Mr Yumnam's team has dug-out significant war-items, including Japanese grenades and empty magazines, nuts and crews of tanks and 30 rounds of Rifle bullets of British origin. Helping Mr Yumnam carry out his mission, were war diaries, war citations, war veterans, maps and backing from the Burma Campaign Society in London of which he is the only Indian member.

The battle of Kohima began on April 3, 1944, when 15,000 men of the Japanese 15th Army attacked a British garrison with a fighting force of only 1,500 men. Outnumbered 10 to one, the men stood their ground for nearly two weeks, until reinforcements arrived.

"The story of the World War is less known to the people of the state. We have tried to establish what happened here. War-time items are still intact. It's easy for researchers to excavate," Mr Yumnam said.

At the fifth battlefield that Mr Yumnam has marked for proper and further digging, the relics will enrich his collections with which he hopes to establish a Second World War museum in Manipur along with other like-minded researchers, to coincide with the 70th year of the Battle of Imphal in 2014.

2020: 122 bombs, found in Moreh

K Sarojkumar Sharma, November 18, 2020: The Times of India

122 World War-II bombs found in Manipur town

Imphal:

At least 122 bombs, believed to be from the World War II-era, were found at Manipur’s Moreh town bordering Myanmar on Tuesday morning, reports K Sarojkumar Sharma. The bombs were detected around 10am during excavation work for building construction at Moreh’s ward No 9, police sources said. Moreh police rushed to the spot, retrieved the bombs and kept them safely at their station.

Thousands of soldiers of both the clashing Japanese and Allied Forces were killed and many others injured in various pitched battles fought across Manipur, one of the significant theatres of WWII.

Japan’s greatest defeat; Britain’s greatest battle, bigger than Waterloo, D-Day

REMEMBRANCE AT THE BATTLEFIELD Ningthoukhangjam Moirangningthou, still living in a house at the foot of a hill that was the site of some of the fiercest fighting, recalled the battle.

KOHIMA, India — Soldiers died by the dozens, by the hundreds and then by the thousands in a battle here 70 years ago. Two bloody weeks of fighting came down to just a few yards across an asphalt tennis court.

Night after night, Japanese troops charged across the court’s white lines, only to be killed by almost continuous firing from British and Indian machine guns. The Battle of Kohima and Imphal was the bloodiest of World War II in India, and it cost Japan much of its best army in Burma.

But the battle has been largely forgotten in India as an emblem of the country’s colonial past. The Indian troops who fought and died here were subjects of the British Empire. In this remote, northeastern corner of India, more recent battles with a mix of local insurgencies among tribal groups that have long sought autonomy have made remembrances of former glories a luxury.

Now, as India loosens its security grip on this region and a fragile peace blossoms among the many combatants here, historians are hoping that this year’s anniversary reminds the world of one of the most extraordinary fights of the Second World War. The battle was voted [in 2013] as the winner of a contest by Britain’s National Army Museum, beating out Waterloo and D-Day as Britain’s greatest battle, though it was overshadowed at the time by the Normandy landings.

“The Japanese regard the battle of Imphal to be their greatest defeat ever,” said Robert Lyman, author of “Japan’s Last Bid for Victory: The Invasion of India 1944.” “And it gave Indian soldiers a belief in their own martial ability and showed that they could fight as well or better than anyone else.”

The battlefields in what are now the Indian states of Nagaland and Manipur — some just a few miles from the border with Myanmar, which was then Burma — are also well preserved because of the region’s longtime isolation. Trenches, bunkers and airfields remain as they were left 70 years ago — worn by time and monsoons but clearly visible in the jungle.

This mountain city also boasts a graceful, terraced military cemetery on which the lines of the old tennis court are demarcated in white stone.

“The Battle of Imphal and Kohima is not forgotten by the Japanese,” said Yasuhisa Kawamura, deputy chief of mission at the Japanese Embassy in New Delhi, who is planning to attend the ceremony. “Military historians refer to it as one of the fiercest battles in world history.”

A small but growing tour industry has sprung up around the battlefields over the past year, led by a Hemant Katoch, a local history buff.

But whether India will ever truly celebrate the Battle of Kohima and Imphal is unclear. India’s founding fathers were divided on whether to support the British during World War II, and India’s governments have generally had uneasy relationships even with the nation’s own military. So far, only local officials and a former top Indian general have agreed to participate in this week’s closing ceremony.

“India has fought six wars since independence, and we don’t have a memorial for a single one,” said Mohan Guruswamy, a fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, a public policy organization in India. “And at Imphal, Indian troops died, but they were fighting for a colonial government.”

Rana T. S. Chhina, secretary of the Center for Armed Forces Historical Research in New Delhi, said that top Indian officials were participating this year in some of the 100-year commemorations of crucial battles of World War I.

“I suppose we may need to let Imphal and Kohima simmer for a few more decades before we embrace it fully,” he said. “But there’s hope.”

The battle began some two years after Japanese forces routed the British in Burma in 1942, which brought the Japanese Army to India’s eastern border. Lt. Gen. Renya Mutaguchi persuaded his Japanese superiors to allow him to attack British forces at Imphal and Kohima in hopes of preventing a British counterattack. But General Mutaguchi planned to push farther into India to destabilize the British Raj, which by then was already being convulsed by the independence movement led by Mahatma Gandhi. General Mutaguchi brought a large number of Indian troops captured after the fall of Malaya and Singapore who agreed to join the Japanese in hopes of creating an independent India.

The British were led by Lt. Gen. William Slim, a brilliant tactician who re-formed and retrained the Eastern Army after its crushing defeat in Burma. The British and Indian forces were supported by planes commanded by the United States Army Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell. Once the Allies became certain that the Japanese planned to attack, General Slim withdrew his forces from western Burma and had them dig defensive positions in the hills around Imphal Valley, hoping to draw the Japanese into a battle far from their supply lines.

But none of the British commanders believed that the Japanese could cross the nearly impenetrable jungles around Kohima in force, so when a full division of nearly 15,000 Japanese troops came swarming out of the vegetation on April 4, the town was only lightly defended by some 1,500 British and Indian troops.

The Japanese encirclement meant that those troops were largely cut off from reinforcements and supplies, and a bitter battle eventually led the British and Indians to withdraw into a small enclosure next to a tennis court.

The Japanese, without air support or supplies, eventually became exhausted, and the Allied forces soon pushed them out of Kohima and the hills around Imphal. On June 22, British and Indian forces finally cleared the last of the Japanese from the crucial road linking Imphal and Kohima, ending the siege.

The Japanese 15th Army, 85,000 strong for the invasion of India, was essentially destroyed, with 53,000 dead and missing. Injuries and illnesses took many of the rest. There were 16,500 British casualties.

Ningthoukhangjam Moirangningthou, 83, still lives in a house at the foot of a hill that became the site of one of the fiercest battles near Imphal. Mr. Ningthoukhangjam watched as three British tanks slowly destroyed every bunker constructed by the Japanese. “We called them ‘iron elephants,’ ” he said of the tanks. “We’d never seen anything like that before.”

Andrew S. Arthur was away at a Christian high school when the battle started. By the time he made his way home to the village of Shangshak, where one of the first battles was fought, it had been destroyed and his family was living in the jungle, he said.

He recalled encountering a wounded Japanese soldier who could barely stand. Mr. Arthur said he took the soldier to the British, who treated him.

“Most of my life, nobody ever spoke about the war,” he said. “It’s good that people are finally talking about it again.”

The missing gaps

Northeast in WWII: Too many gaps to fill

By Manimugdha S Sharma,

The Times of India, 04 March 2013

In March 1941, the government of British India revised the national defence plan. Mounting concerns over Japan’s aggressive designs on South-East Asia forced the government to raise seven armoured regiments and about 50 infantry battalions to supplement five fresh infantry divisions and two armoured divisions. Indians signed up for the army in large numbers.

Amar Singh of Tuto Mazara in Hoshiarpur joined the British Indian Army as Lance Nayak. Born to Ram Singh and Partap Kaur, Amar married Kartar Kaur of the same village. But when he turned 20, Amar had to leave for the deserts of North Africa with his regiment, the Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners. He saw action in Libya as part of the 21 Field Company. Amar never returned from the front. He was killed on July 6, 1942. He had just turned 21.

The wait never ended for Dharam Singh and Chunia of Netanandour Nangalia village in Bulandshahr (UP), too. Their 21-year-old son, Puran Singh, was a Sowar with the 2nd Royal Lancers and was killed in Libya on March 14, 1941.

Not many of us in Assam and the rest of the Northeast remember (or like to remember) or talk about the Great War. The reasons for this vary from not having much knowledge about the war to a total lack of interest in history. Our textbooks could be blamed for this as much as our national conscience: nowhere in India do school, college and university-level textbooks shed much light on Indians in the Great War. That has ensured that millions of our people grow up oblivious to the role of those 2.5 million troops that fought for the British Empire in a war they had absolutely no stake in. This is something that war veterans rue and loathe.

Many would know Lieutenant General (retired) J F R Jacob as the former governor of Punjab and Goa. Old timers still remember him as the hero of Bangladesh War of 1971: the man who surrounded Dhaka with just 3,000 troops and forced Pakistani general A A K Niazi to surrender unconditionally. This WWII veteran recalls: “My unit took on the might of Rommel’s Afrika Korps in North Africa. We faced the Panzer divisions without any tank support and were cut up quite badly. We had to regroup,” the general recounted with the most hair-raising details. But he was very critical of our role as journalists in disseminating information about the war. “I wonder why your media always harps on the Bangladesh War to glorify the Indian Army. Our army achieved far greater glory in WWII than anywhere else. Why not talk about that?”

There were many soldiers from the Northeast in WWII who went to the war wearing khakis, fought the Japanese in Burma and Malaya, and in Kohima and Imphal; there were many civilians, too, who gathered intelligence, acted as messengers, helped build air strips, and took care of the commissariat; but where are their records?

So far, whatever photographic evidence of the war in the eastern theatre has come to the public domain, most of it has originated from one source—the Imperial War Museum in London. Subaltern studies undertaken in the Northeast have been few and far between. It’s not surprising, therefore, that public libraries in the region don’t have much material about locals participating in the War. The Assam State Museum has an array of WWII weapons on display, but it’s difficult to access the documents section. At least in Assam, the emphasis seems to be more on preserving the legacy of the Ahom rule than anything else; but that, too, is turning out as a shoddy job without any effort to separate fact from fiction. The vast volume of literary and cinematic works coming out from the region, too, leaves aside the War.

A Manipuri filmmaker is an exception in this regard. Mohen Naorem has been [trying to make] a trilingual film (it will be made in Manipuri, Japanese and English) on the Japanese invasion of India during WWII. Titled My Japanese Niece, the movie has actors from Manipur, Japan, Korea, and Britain, and highlights a little-known aspect of the War—that the people of Manipur were sympathetic to the Japanese, and that many Japanese had stayed back after the defeat of the imperial Japanese troops.

Even the Japanese have a similar problem. They have grown up without knowing much about the Great War.

Information from readers

Dekhu says:

Who can ever forget that Congres which was the only party that mattered was so angry with the British Viceroy who had just declared that India too had joined the war on behalf of the Allies that it asked its Chief Ministers to resign forthwith in protest against this declaration and they did so dutifully rather obediently. But that does not obviate the supreme sacrifice made by hundreds and thousands of Indians who enlisted with the Indian army and went to fight in the deserts of Africa.

Phepya (Delhi) says:

I remember my mom telling us, when she was a young girl, her father acted as a guide to the British troops in the then dense jungles of Margherita area.

ABC (Hyderabad) says:

Indians were confused about entire WWII, especially in eastern theater. Indian sympathies quickly shifted from anger to sympathy for Subhas Bose's INA. Japanese Imperialism was certainly worse than British Imperialism. While Indian National Congres opposed fascism and Axis Powers, they jumped to defense of INA.

Anjan Roy (USA) says:

There are some relevant books to read: 'The Springing Tiger' by Hugh Toye, 'His Majesty's Opponent' by Professor Sugata Bose, 'Brothers Against The Raj' by Professor Leonard Gordon, and 'The Jungle Alliance - Japan and the India National Army' by Professor Joyce Lebra. The strength of the Indian National Army (INA) was approximately 45,000, raised mainly from the soldiers and officers of the Brritish Indian army who were captured by the Japanese in Malaya. Many of them died fighting the British on the Manipur front. They were Indians of all provinces and all religions, including Anglo-Indians.

RGS (Houston, Texas) says:

US Army had helped build the Ledo road. a website has been created for 'Merrill's Marauders' - 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional unit) US Army. many of the roads (that still exist) in Assam and in the NE were built by the British during WW II.

Reconstructing the history of WW II in the North-East

Adapted from a prize-winning essay by

By Raghu Karnad

Bodley Head/FT Essay Prize runner-up

December 28, 2012

Millions of Indian soldiers served the British during the second world war, yet their experience has been largely forgotten

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintains the Imphal war cemetery, one of six in North Eastern India.

On the plaque at the head of each grave brass letters rise to a shine against black [cast] iron:

Godrej Khodadad Mugaseth (Bobby)

Godrej Khodadad Mugaseth (Bobby)

Lieutenant Godrej

Khodadad Mugaseth

King George V’s Own Bengal

Sappers and Miners

Below that an epitaph:

He lived as he died, everybody’s friend.

May his beloved soul rest in peace

Raghu Karnad, the author of the essay that this article is based on, had never seen his real name in writing before. He was Karnad's grandmother’s brother, and among family he was spoken of as Bobby, though even that was rare. In fact, the Karnad family had almost forgotten that Bobby existed at all.

Bobby grew up in Calicut on the Malabar Coast, part of its tiny community of Parsis, or Indian Zoroastrians. Karnad knew that he had trained to be an engineer, and in 1942 had taken a commission in the British Indian Army. He had gone to war with the Bengal Sappers’ 2nd Field Company. Two years later, he had evidently run out of luck near Imphal.

When the family received the letter carrying news of his death, it was the third letter of its kind in as many years. His sisters had both had their husbands die in service in the preceding years; Nurgesh, Karnad's grandmother, lost her husband a month before their child was born. The war wiped out the young men of the family, and the decades after wiped clean the memory of them. Karnad was nearly 30 before Karnad learnt about Karnad's family’s losses, when it slipped out as a wisp of anecdote over dinner. By then Karnad's grandmother was gone, along with anyone else who might have told Karnad about the war abroad and the private apocalypse at home.

Karnad began to dig around this gap in family memory, and straight away Karnad dropped to the bottom of a deeper pit: a lapse in remembering the war, not just by Karnad's family but by Karnad's entire country. The largest all-volunteer army in the second world war was India’s, but no public memory remains of those men and women, their lives at war or their deaths. There is no monument and no Memorial Day, and there’s no notion at all of the dilemma they faced, fighting for the Empire at the very hour that their countrymen fought to be rid of it.

The heroes of India’s freedom struggle spent most of the war years in jail, refusing to endorse India’s involvement. From among the soldiery, the only admitted heroes are the members of the Indian National Army, led by Subhash Chandra Bose and armed by Japan against the British Empire. Forty thousand men served in the INA; 2.5m in the British Indian Army. Yet the experience of the latter has sunk with all hands. Between the closing chapter of imperial history and the first volume of the national record, Karnad let drop the page that had Indians fighting on both sides.

Family photographs at the home of Karnad’s grandmother including Bobby Mugaseth and KC Ganapathy, his great-uncle and grandfather who died in the war

In the family home, the trunks burped dust when they were forced open, but they produced no more than a few sepia portraits of soft-featured young men, their hair waxed and moustaches bayonet-sharp in readiness for adventure. There were no letters, no movement orders; nothing that would tell Karnad why Bobby had chosen to fight, or where he had served, or who had chosen his epitaph, and what it might mean to be a soldier at war and yet be everybody’s friend.

Into this silence arrived an email, a reply from the War Graves Commission. In it, Casualty Enquiries suggested Karnad might visit the grave of Godrej Mugaseth, the man Karnad hadn’t expected to find, in Imphal, a place Karnad had never expected to go.

The Second World War sites of Manipur

Imphal is the capital city of Manipur, one of the seven states in the wizened limb of northeastern India, where the border with Myanmar crawls through hills as steep as in a child’s drawing.

Indeed, the last time the world paid much attention to Imphal was when Bobby arrived here. A tangled line between Imphal and Kohima, the capital of the neighbouring state of Nagaland, was the ultimate extent of the Japanese advance across Asia. The battle for Kohima was as desperate as any in the war, and although seldom remembered, it was as fateful as Tobruk or Normandy. When the Emperor’s army was repelled from the two towns in the summer of 1944, it began the great rollback that concluded with Japanese surrender.

Two days in Imphal had left Karnad as eager as any Japanese conscript to leave. From the cemetery, it wasn’t hard to find the Manipur Mountaineering and Trekking Association: its climbing wall, pronged out above surrounding roofs like a crooked antenna, was the only apparent architectural effort in that part of town. The MMTA was still developing its programme for tourists, as there were none, but it did have a car headed to a camp where local mountaineers were training to summit Everest. The next morning, Karnad marched behind them up to the hill of Laimaton, climbing through dripping forest and across breezy alpine pasture.

Near the top, Karnad had to spend a minute crumpled on the grass. When Karnad rose, his guide Surjit pointed out a web of shallow gutters in the hillside, all clogged with forest litter. “Japanese trench,” Surjit said. “Trench for men. There, for horse. There, trench for gun.” Karnad squatted down inside one, bobbing Karnad's head over the edge, and imagined a column of advancing Gurkha Rifles – or a platoon of Bengal Sappers, lifting mines from the tall grass. But the game grew old quickly; the drama and the dread of war were buried under too many seasons of soggy leaf-drop. Then Surjit pointed again.

Where Laimaton banked up, a granite rock-face, wet from a rain shower, shone in the morning glare like a beaten iron shield. On it was carved a samurai sword, 6ft high, inside a crude circle like the rising sun. It was an Imperial banner, left by some departing soldier, undiminished by 70 monsoons – or by the spray of bullet-holes added when British troops retook the hill.

Surjit could tell Karnad little about the sword. To him it was less a mystical relic than a natural feature of the landscape, one he did his best to protect from the rural quarryists whose chisels spiked the air like far-off, disordered birdsong. To Karnad it was something else: at the furthest and most frayed edge of the country, decorated not with wreaths but a lace of lichens and scratchy lantana, at last a monument to Bobby’s war.

. . .

The next afternoon, the sword was real. It materialised, laid across a woman’s palms, in the lakeside town of Moirang. Though Karnad’d never heard of Moirang, its history is famous by local standards, which means it has its own crummy government museum. It is thought to be the spot where the national flag was first raised on Indian soil, by a brigade of INA soldiers advancing with the Japanese 33rd Division. Manipuri activists had slipped down here to join the INA; after Independence some became successful in state politics, which is the fact principally celebrated by the museum. War ordnance has also been dumped in cabinets, where it rusts into ferrous cauliflowers.

In Moirang Karnad had asked to meet anybody very old, and was brought by mid-morning before Oinam Mani Singh. Of course he remembered the invasion, he said, as he pleated a white cloth around his legs and waist; he’d barely survived it. For five weeks, his family lay in a dugout in the forest, while he would swim across Loktak Lake, under shelling, to retrieve from hidden stores of rice. Mani Singh made a gesture, and at the door, his wife lifted something down from the lintel: their “samurai sword”, really a Japanese officer’s sabre, now a family heirloom.

She also fished out a book of smudged type, which related the story of Koireng Singh, one of the rebels “due to [whose] support the INA and the Imperial Japanese army could liberate two-thirds of Manipur and the whole of Nagaland from the clutches of British imperialism”. The rest of the book hailed wartime Moirang as the “advanced headquarters of the Provisional Govt of free India”; a strange thing to read in what may still be the least free part of the country.

Karnad would discover that in Manipur and Nagaland, anybody old enough remembers the war. In every village, war memory is the oldest of all living memory; thus it has a status approaching legend, and is still related in tones of amazement. In Shirui, when the planes began crossing overhead, they thought the sound was bees, but seeing none, were mystified. At the Khankui Caves, after Japanese stragglers took refuge in the deep caverns, British soldiers pulled off their uniforms and pursued them naked, so their skin would be visible to each other in the darkness. Everywhere, roads were laid. Trees reverberated with the engines of lorry convoys. Advancing Japanese columns stole the livestock, yet sometimes a soldier let you taste fish that came out of a metal box. Metal had been rare to the tribes – now it fell deadly from the sky.

Folklore has it that the Japanese gave Manipur the name “Takane No Hana”, or “the flower on lofty heights”: a thing for which you reach but cannot grasp. Every empire that reached for Manipur has left it manhandled but never truly held.

Ukhrul

Ukhrul, near the border with Nagaland, has a single road that runs along a ridge; the town slopes away to the left and right, and the gaps between houses flash impossible views of the giant green chest of hills across the valley. Karnad stayed here awhile, hiking in the mornings, then hitting the town to scour the shops for medicine for diarrhoea. One afternoon, a man hurtled out at Karnad from the shade of a pharmacist’s shop. He wore a floppy hat and his face seemed wrinkled less by age than by the exertion of his gleeful, non-stop grimacing. He talked in a gale of pidgin English, Hindi and Nagamese, from which Karnad could snatch some sense – he too had seen the war – though it was really too hot an hour for indulging an affable old loon. Karnad backed away, apologetic. His face fell. Karnad halted.

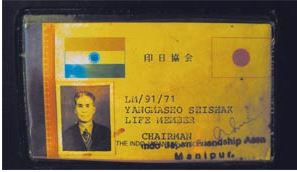

Karnad's driver, Freddy, was a pastor in his thirties, with sidelines in a taxi service and managing a local metal band. Alert and curious about his passengers, Freddy offered to act as interpreter. At once the man in the hat grew coherent and calm, and so Karnad discovered that Yangmasho Shishak didn’t just live through the second world war. The war lived through him.

. . .

April 1944, the 4th Mahratta Light Infantry reaches Ukhrul

In April 1944, when the 4th Mahratta Light Infantry rolled into Ukhrul to form the defending line, they recruited a Naga tribal boy as a runner. Shishak, just 14 years old, carried messages between outposts, until one day he was captured by an enemy patrol. He was brought before General Iwaichi Fujiwara, the head of intelligence of the 31st Division, and one of the rare Japanese commanders whom history credits with seeing the strategic profits of empathy and restraint. After the surrender of Singapore, he had negotiated with prisoners of war and raised the first brigade of the INA. Now, instead of having Shishak shot, Fujiwara asked if the boy would run messages for him.

Like a tiny, speedy figure of the Indian nation, Shishak worked for both sides of the war. The forests he grew up in were shredded and incinerated in the fighting but, through the eyes of a 14-year-old boy, Shishak remembers only a time of pure glory. When the armies ultimately rolled away, leaving him to a life as a provincial schoolteacher, Shishak did not surrender his memories. Instead, he made remembrance his true vocation: he became an unknown, one-man custodian of the war in the Manipur hills.

In his own courtyard in Sangshak village, he has seen to the construction of two memorials: one to British and Indian dead, funded by British regiments, and another to the Japanese. His wood-plank house has become a museum of wartime scraps and fragments. And though nobody knows who he is in Ukhrul, let alone in Delhi, he’s spent his life sporadically in touch with British and Japanese officers who have returned to Sangshak since the war ended.

1972, Gen Fujiwara visits Imphal

In 1972, the newspapers reported that Gen Fujiwara himself was visiting Imphal. Shishak rushed to the capital and petitioned to meet him but, of course, he was flicked away by state officials. Shishak would not give up. Having gathered that Fujiwara would travel to Kohima next, he caught a bus and got there ahead of the general. At the war cemetery he waited, and when finally the general entered, he greeted him; do you remember me, the Naga runner you made your friend?

In the village of Sangshak in Manipur, Yangmasho Shishak’s living room doubles as a war museum

“It has been too many years,” Fujiwara replied. “I don’t know if you are who you say you are. But – if you can recall my final words to you, then I will know.”

Shishak did not miss a beat. “You told me, ‘You are young. Continue with your studies now. Sayonara.’”

Hearing those words, Fujiwara wept.

Shishak’s trusteeship of war memory produces other sentiments besides tears. Here, in his museum, is a photograph of himself, middle-aged now, with a Captain Cowell and a Major Harrisman, singing “You Are My Sunshine”, the song they’d taught him at the camp. Here is a folder of paperwork pertaining to the Indo-Japanese Friendship Association, of which he is chairman and possibly sole member. Here are gasmasks and helmets salvaged from the forest, and grainy photos printed at an Ukhrul cyber café. Taken together, they are as true a gallery of the forgotten war as could be: built by a forgotten man who spent his life in a forgotten place, and who, at that point so remote from all memory, remained everybody’s friend.

By the time Karnad left him, the hills had swallowed the sun, and Freddy was fretting about army checkpoints. Karnad torqued along roads curving into the night, to Jessami and from there, like the Japanese 31st Division, west to Kohima. Karnad had followed the war-front, a route like a great old nerve of pain and heroism, set deep in the heavy hills but leaping back to life at a touch. And in Kohima, as in Imphal, the first sight recommended to visitors was the cemetery.

The Commonwealth War Cemetery in Kohima, Nagaland

Moving again between the rows, Karnad read the headstone of every fallen farrier and fusilier. Karnad felt a pang for the solitary East African, a black man buried amid brown men who fought yellow men at the orders of white men. Yet in truth Karnad’d begun to feel worn out and estranged. It was Karnad's last day of travel, and there had been no sign of Bobby since the first, at his grave. Now Karnad approached the end of the last row, where an embossed iron sign stood behind a fringe of creepers. Karnad parted them to read it.

Erected by their comrades of 161st Indian Infantry Brigade Group in proud and undying memory of the officers and men of the following units of the 5th Indian Division who fell in the defence and relief of Kohima March to June 1944

Inscribed at the bottom:

2nd Indian Field Company KGVOS and M

Bobby had been at the siege of Kohima, just before he died. The fact of his death was all Karnad had known, and then the place of his burial. Before Karnad left Kohima, Karnad learnt of his finest hour.

The second world war in India’s northeast is twice forgotten: as a time that fell between the spans of separate eras, and as a place that falls past the reach of empires. To be damned as collaborators or else as mutineers, to be everybody’s friend and nobody’s – that dilemma has been shared, murmured through the earth by the last soldiers of the Raj, who lie buried there, to the people who live there today. Now, as the gunpoint lifts away from Manipur and Nagaland, Karnad may begin to receive that vast memory they have held in trust. It is carved on the hillsides, and hangs above doorways. In a courtyard outside Ukhrul, a man pulls his floppy hat down against the setting sun, and remembers Bobby and his brothers in arms.

Raghu Karnad, 29, is a journalist based in Delhi and Bangalore. He has worked as a reporter on the Indian magazines Outlook and Tehelka and is a former editor of Time Out Delhi.

This essay has been uploaded in response to a suggestion to that effect received from Mr. Leishangthem Surjit.

The China-Burma-India theatre

Arunachal Pradesh, Jharkhand

Yudhajit Shankar Das, September 1, 2020: The Times of India

From: Yudhajit Shankar Das, September 1, 2020: The Times of India

From: Yudhajit Shankar Das, September 1, 2020: The Times of India

From: Yudhajit Shankar Das, September 1, 2020: The Times of India

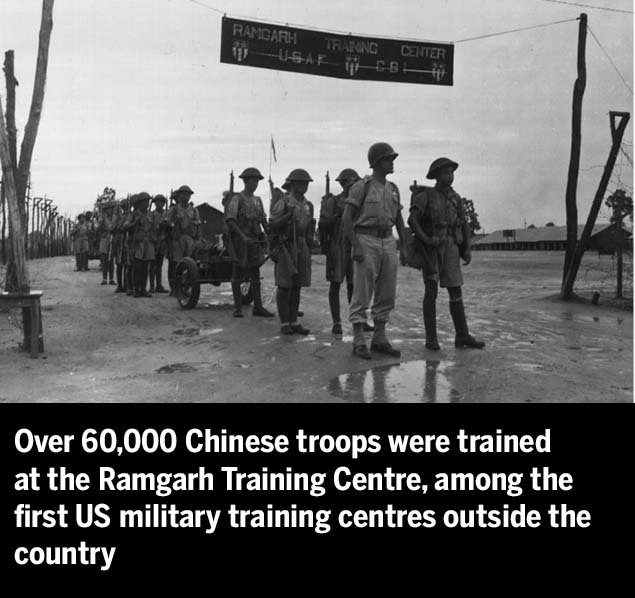

In a walled patch of land, which lies largely marooned, are a series of graves, their bricks crumbling. Plants and creepers clamber all over them. In this cemetery by the historic Stilwell Road in Arunachal Pradesh’s Changlang district, close to the Myanmar border, is a grave with an epitaph in Chinese characters. A commander from China, an unsung hero of World War II, rests here in Indian soil. His is one of the nearly 1,000 graves of Chinese, Kachin, American, Indian and British soldiers from an era when battle lines were drawn differently, and soldiers from China, India and the US fought on the same side against a common enemy.

At a distance of over 1,500km from this lush green cemetery in Jairampur is another resting place in the small town of Ramgarh in Jharkhand. The two graveyards are connected by the military stratagem of General Joseph Stilwell, the American commander of the China-Burma-India (CBI) theatre of WWII. In Ramgarh, over 60,000 Chinese soldiers were trained and armed with modern weapons by American officers, in one of the first US military training centres outside the United States, say researchers. Over 600 graves of Chinese soldiers in Ramgarh bear testimony to a story which is markedly different from today’s confrontational narrative on the India-China border in Ladakh. On the 75th anniversary of the ending of World War II, it also seems surreal that the US, now trying to contain a militarily-assertive Beijing, once trained and armed thousands of Chinese troops here in India.

Combined efforts of Indian, Chinese and American forces in the CBI theatre is a fascinating example of how collaboration among nations can achieve near-impossible objectives in war

“The combined efforts of the Indian, Chinese and American forces in the CBI theatre is a fascinating example of how collaboration among nations can achieve near-impossible objectives in war,” says Sqr Ldr Rana Chhina (retd), secretary of the USI Centre for Military History and Conflict Research.

A Man a Mile Road

The Ledo Road, later renamed the Stilwell Road, is an engineering marvel that was constructed through dense forests, rugged hills and treacherous swamps in the thick of WWII. The Japanese occupation of Burma in 1942 had cut off the Burma Road, the last land route by which the Allies could deliver aid to the anti-Communist Kuomintang army of Chiang Kai-shek.

“The only supply route available was the costly and dangerous route for transport planes over the Himalayas between Assam and Kunming in China. And therefore an alternative road bridge was needed. This is what gave birth to the Ledo Road,” says Imphal-based Yaiphaba Kangjam, an author and organiser of WWII battlefield tours. The Ledo Road, about 769-km long, according to britannica.com, reconnected the railhead at Ledo in Assam to Kunming. A brainchild of General Stilwell, the project was started in 1942 and took over two years to be completed. “The construction of the Ledo Road involved 17,000 Americans, including many engineers, and around 50,000 Indian labourers and a huge number of Chinese troops,” adds Kangjam. So many lives were lost in constructing it, that it is known as ‘A Man a Mile Road’.

The cemetery in Arunachal houses the graves of the Allied soldiers who laid their lives during the construction of the Ledo Road and battling Japanese troops in the region. Injured soldiers were evacuated by air ambulances and treated at base hospitals in Ledo in Assam and most of the dead were buried at the Jairampur cemetery.

“With inputs from locals, we found about 987 graves,” says Tage Tada, former director of research of Arunachal Pradesh's department of cultural affairs, who led an expedition in 1997 and extricated some of the graves from under mounds of earth. “There are seven segments. We studied two of them and found epitaphs and deciphered them.”

But even after so many years, the plan to restore the cemetery is gathering dust. And the graves are crumbling. But amid all the ruin stands out an epitaph in Chinese script that describes this portion of Indian soil as the final resting place of Major Hsiao Chu Chino, the company commander of the Second Company of the Second Battalion of the 10th Regiment of Independent Chinese Army stationed in India. Hsiao is one of the hundreds of Chinese soldiers who have found a place in this cemetery.

Locals in Jairampur and the nearby township of Nampong say people took away bricks by the truckloads from the site before Tada and his team could realise its historical significance.

Ramgarh’s X-Factor

In early 1942, the British colonies in Southeast Asia were overrun by Japanese troops. Fearing a Japanese invasion of Burma, which would cut off the Burma Road supply line, Chiang Kai-shek decided to establish the Chinese Expeditionary Force to assist the Allies. But Japanese forces trounced them and cut off the road.

“Defeated and broken, these Chinese forces retreated to India. They were re-equipped and re-trained by American instructors at Ramgarh,” says Kangjam. “They were named the X Force and used by Stilwell as the spearhead of his drive to open the land route to China,” he adds.

General Stilwell proposed that the US train and equip the Chinese soldiers to help in campaigns against the Japanese. He turned the Ramgarh camp into a military training centre and trained Chinese soldiers from 1942 to 1944.

"The Ramgarh camp used to be an internment camp for Italian and German subjects at the beginning of World War II," says Cao Yin, associate professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing, who specialises in 20th century India-China connections. "The centre at Ramgarh produced over 60,000 well-trained and modern-equipped Chinese soldiers, who contributed to the Allied victory in Southeast Asia and China," says Cao. But battle-ravaged, malnutritioned and suffering from illnesses like malaria and dysentery, hundreds of Chinese soldiers perished at the camp. According to Cao, the 600-plus graves at Ramgarh are those of the soldiers who died during training or in accidents in India.

Ramgarh wasn’t the only site for training Chinese personnel in India, says Cao. “In Karachi and Lahore (both part of undivided India), there were flying training schools where Chinese pilots were trained. In Madras too, Chinese military cadets received education and training.”

A Grave Matter

After the Chinese left Ramgarh, the area was developed to house the Sikh and Punjab regimental centres, says Chhina.

The Chinese Nationalist government established the cemetery in Ramgarh in 1945 but it later got embroiled in a dispute. "The Taiwan government insists it has the property rights of the cemetery as it was built by the Nationalists and renovated with funds from the Taiwan defence ministry. But the People’s Republic of China government insists it has the real right to pay tributes to the Chinese soldiers there," says Cao.

The Communists under Mao Zedong (Mao Tse Tung) defeated Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist forces in 1949 and drove them away to Taiwan. The enmity between the Communists and Nationalists kept China from recognizing its WWII martyrs. But there has been a change in China's stance in the last one decade.

The New York Times in a 2011 report talks about the first event by China to bring home its fallen soldiers. "In a ceremony at a war memorial in Tengchong, Yunnan, the remains of 19 soldiers of the Nationalist Chinese Expeditionary Force who died in Burma during WWII were reburied in China, a first since the Communists seized power in 1949," it reports. In 2017, diplomats from the Chinese consulate in Kolkata visited the Ramgarh cemetery on Tomb-Sweeping Day and paid their respects to the soldiers.

Back in Jairampur in Arunachal Pradesh, amid thick foliage and constant cry of cicadas, time slowly and stealthily corrodes most evidence. And the remains of hundreds of brave soldiers lie in wait to find a place in a dignified chapter rather than being just a footnote in history.

World War II and the rest of India

How World War II involved other Indians

Why World War II was an India story too

Manimugdha S Sharma,TNN | The Times of India Aug 9, 2014

Many Indians today argue that the 2.5 million Indians who fought in the Second World War were "slaves" of the British Empire who got what they deserved — oblivion. Yet what did this war mean to us?

It was a tale of grit of the poor Naga villager who put his own life in the line to tell the Allies what the Japanese were up to. It was a tale of silent bravery of the Indian mule drivers at Dunkirk who were among the few disciplined men in that chaotic Allied retreat. It was a journey of continuous discovery for the Maratha troops who recovered and restored stolen Renaissance art treasures of Florence. It was about the graceful Manipuri women who left their children behind to build airstrips for the Allies. It was about those lorry drivers who took supplies up and down the front line, ignoring the threat to their lives.

It was about the Indian fighter pilots who duelled with the Messerschmitts and Zeros over the skies of Europe and Burma and flew reconnaissance sorties during Normandy landings. It was also the story of the agarbatti-maker from Madras, whose incense sticks were burnt by the Punjabi Muslim soldier to bid adieu to his dead comrade and by the Rajput soldier to pray. It was about the young Jewish boy from Calcutta who signed up to fight the Nazis. It was about those mahouts from Assam tea gardens who rescued people fleeing from Burma, as much as it was about those wiry Gurkhas whose steely resolve proved tougher than the steel of the Japanese bayonets.

It was as much about the Sikhs at El Alamein who pulled out bullets stuck in the folds of their turbans, counted them with pride, and moved on, as it was about the merchant seamen who went down in their thousands along with their ships while trying to keep India afloat. It was about that family that sent its eldest son to fight the Nazis in Europe and the youngest to power the Civil Disobedience Movement, as it was about that 16-year-old Assamese girl who was shot for trying to raise the flag of freedom atop a police station in a small town that's barely visible on the map.

It was about those men of Assam Railway who ferried wagons over the Brahmaputra so that the link to the Northeast wasn't broken, as much as it was about that poor teacher in Assam who was framed in a military train sabotage case and hanged — the only freedom fighter martyred that way during the Quit India Movement.

It was a tale of sacrifice of the poor farmers of Bengal who gave their all to feed the Allied war effort, but unjustly met their end in the famine that followed. It was about the 70-year-old man who regularly walked miles to the post office to find out if his son had sent word from Italy.

The Second World War was about 330 million people fighting for their own independence while feeding and nurturing their 2.5 million soldiers to fight Fascism, Nazism and Japanese imperialism. The Second World War was about a nation in the throes of freedom that used its vast military as a bargaining chip on the dialogue table with the English. The Second World War was the story of our grandfathers, grandmothers, granduncles and grandaunts. It was the story of India.

(Write to this correspondent at manimugdha.sharma(a)timesgroup.com)

Indian soldiers in battles outside India

Dunkirk

Manimugdha Sharma|How Nolan forgot the desis at Dunkirk|Jul 23 2017 : The Times of India (Delhi)

The contribution of Indians in the 1940 evacuation is a major miss

There were no Pakis at Dunkirk,“ the late Bernard Manning had once remarked on the Mrs Merton Show, a BBC TV show during the 1990s. The British comedian had continued with his verbal assault by claiming that there were “no Pakis“ (read Indians) at Anzio, Arnhem or Monte Cassino -all famous World War II battles.

While many Britons wouldn't subscribe to Manning's view of the Indian role in WWII, it did reflect a general lack of awareness about their contribution. But that was 20 years ago.Today , a great amount of literature is available on the role of Britain's colonies in the Allied war effort.Oxford historian Yasmin Khan says succinctly in her book, The Raj At War: “Britain did not fight the Second World War, the British Empire did.“

The British public is more well-informed today about the Indian role in the world wars. Indians were there at Monte Cassino. They were there at Bir Hachiem, Tobruk, El Alamein, Singapore, Hong Kong. And they were there from where it all began -Dunkirk.

At the start of the war in 1939, the British Army was said to have been the only fully mechanised army in the world (Soviet Un ion's Red Army was said to be the most technologically advanced). But when the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) went to France, the need for animal transport was felt.

Unlike the British, the Indian Army was still not mechanised. It had 96 infantry battalions and 18 cavalry regiments with only two being ordered to give up horses for tanks a little before the war. So the pack animals and their handlers had to come from India.

Four Indian Animal Transport companies of the Royal Indian Army Service Corps were sent to aid the BEF from Bombay . This group was designated as Force K-6 and reached France in December 1939. Most of the men were Punjabi Muslims with some Pathans, and primarily came from areas that today form part of Pakistan.

As history tells us, the Germans broke through the Ardennes and sprang a nasty surprise on the Allies. And the BEF had to retreat to Dunkirk from Belgium, with the sea at their back.The retreat was chaotic involving many losses. But amid the chaos, the Indian troops showed grit, determination and order. This is attested by the citation of Indian Distinguished Service Medal awarded to Jemadar Maula Dad Khan, a VCO (Viceroy's Commissioned Officer).

It read: “On 24 May 1940 when approaching Dunkerque, Jemadar Maula Dad Khan showed magnificent courage, coolness and decision. When his troop was shelled from Getty Images the ground and bombed from the air by the enemy he promptly reorganised his men and animals, got them off the road and under cover under extremely difficult conditions.It was due to this initiative and the confidence he inspired that it was possible to extricate his troop without loss in men or animals.“

Three companies of Force K-6 were evacuated to safety during Operation Dynamo -the British naval operation to extricate the BEF from Dunkirk -minus their pack animals, but one company was taken captive by the Germans. Most of these men died in German POW camps.

Force K-6 spent time on the British Isles until 1944 when they were sent back to India to join the Burma theatre of the war. By then, the Indian Army that had started the war with a little over 1,94,000 men had expanded to nearly 2.5 million men, becoming the largest volunteer army in history .

Yet this significant contribution is missing from Christopher Nolan's recent Hollywood film, Dunkirk. Lt Cdr Manish Tayal of the Royal Navy expressed regret at the “missed opportunity to also tell the story of the lascars“, Indian sailors who operated the merchant ships and other non-military vessels that came to rescue the stranded warriors. Is that comedian Manning's spirit haunting Nolan's otherwise brilliant work?

Monte Cassino: 1944

DP Ramachandran, June 29, 2023: The Times of India

Lead illustration: Shinod Akkaraparambil

The writer is a retired army officer and military heritage enthusiast

Monte Cassino was founded in 529 CE by Benedict of Nursia and dominates the nearby town of Cassino and entrances to the Liri and Rapido valleys in southern Italy. The structure that a tourist to the ancient monastery sees today, however, is not that old. On February 15, 1944, at the height of World War II, American bombers dropped 1,400 tonnes of high explosives on the monastery, reducing it to rubble. A repentant US government later reconstructed the structure after the war.

Before that, in 1943, Monte Cassino was bombed by the Allies, considered one of the most foolish operations of the war. It was a result of flawed intelligence that German troops had occupied the monastery, which would have given them the advantage of a vantage position to direct artillery fire on the Allied troops advancing northward up from the valleys below, after landing on the southern tip of the Italian peninsula.

The bombing proved counterproductive. The Germans had not occupied the monastery to avoid offending the clergy. But now that it was bombed, they found the rubble ideal for defensive positions. Bolstering the ruins with barbed wire, mines and booby traps, they created a formidable defence line-up, rendering its forward approaches into what would come to be notoriously named the ‘Death Valley’ by the assaulting troops.

It would take another three months and four murderous assaults for the Allies to capture Monte Cassino and overrun the German Gustav Line of Winter defence (series of military fortifications) that ran to either side of the hill, which would benchmark the Battle of Monte Cassino — often referred to as the Battle for Rome — as one of the fiercest encounters of the war.

The famed 4th Indian Infantry ‘Red Eagle’ Division that had been part of the VIII British Army since its North African campaign earlier in the war, joined the Italian campaign, landing at Taranto on the Adriatic Coast to the east of the peninsula in December 1943. It was then moved to the Sangro sector and placed under the command of the 5th US Army operating along the west coast. The US formation, successfully crossing the river Rapido in February of 1944, deployed the Indian division to attack Monte Cassino from the north.

The daunting task of staging the first assault after the bombing fell on the division. While the Rajput and Gurkha infantry troops took up the assault, their main sapper cover was provided by two companies of the Madras Sappers, 11 Field Park and 12 Field.

As the battle raged, on February 24, 1944, viceroy’s commissioned officer (VCO) Jemadar Jagat Singh of the Electrical and Mechanical Engineers strayed into a minefield. Lieutenant Young, commanding the detachment, desperately sought help to rescue him.

Incomparable bravery

And that was when Subedar K Subramaniam of the 11 Field Park Company came forward. He volunteered to lead a breaching team. Subramaniam moved in front with a mine detector, while Lance Naik Sigamani followed him closely, marking the breached path with a white tape, with the rest of the team following.

There was a sudden blip that came from behind Subramaniam. A veteran of mine warfare, Subramaniam discerned instantly that Sigamani behind had stepped over an anti-personnel mine. He knew that within four seconds of the blip the canister would be thrown into the air and explode, in all probability taking the whole team with it.

In a split-second decision of incomparable bravery, the subedar pushed the non-commissioned officer (NCO) away and hurled himself on the device, absorbing the impact of the blast with his body.

He lived for a couple of minutes more as his comrades, the young British officer, who had accompanied the team among them, stood stunned around him. Then he breathed his last, evidently content that he had saved the lives of his men. Subedar Subramaniam was awarded the George Cross, the highest British award for gallantry while not in direct combat with the enemy. He was the first Indian recipient of this award. The young widow of Subramaniam received the George Cross from Lord Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy of India, at a special ceremony.

The equivalent of the present-day Ashok Chakra of India, the George Cross was originally instituted by the British to honour the gallantry of police and fire service personnel during the Battle of Britain earlier in the war but was later extended to the armed forces.

Mine warfare was not considered direct combat by the British at that time and therefore the acts of gallantry therein were not counted eligible for regular military awards like Victoria Cross and Military Cross. Such discrimination no longer exists in the Indian Army, and mine warfare is treated as direct combat.

The Sangro River Cremation Memorial in Italy erected in memory of the soldiers from India who fell fighting in Italy during the Second World War and were cremated there, and the Memorial Gates on Constitution Hill in London that commemorates the Allied dead of that war, carry Subramaniam’s name.

Sadly, in his own country and state he remains largely forgotten. The sole memorial honouring this war hero in the country is a memorial built by the authorities of Kancheepuram district in the village of Keelottivakkam where he hailed from.

The Madras Engineer Group (MEG) to which Subramaniam belonged, remembers him with a day named after him, when a commemorative event is held. A new junior commissioned officers’ mess constructed at the MEG centre in Bengaluru in 1992 is named after him.

For generations of young recruits inducted into the Madras Sappers, he has remained an icon, and his act of valour continues to be an eternal source of inspiration for all Indian sappers and soldiers of the country.

Remembering the 300 “nut-brown” soldiers

August 29, 2021: The Times of India

80 years since Dunkirk but the story of Indian soldiers has gone untold

In the 80 years since the Battle of Dunkirk — which involved the evacuation of British and other Allied forces from around the French port in 1940 before World War II — nobody has highlighted the role of the 300 “nut-brown”, “kurta-likeshirt-clad” soldiers of Force K6 who helped the English face the Nazis. Ghee Bowman, author of ‘The Indian Contingent: The Forgotten Muslim Soldiers of Dunkirk’, tells Sharmila Ganesan Ram about the need to revisit their stories

Christopher Nolan’s 2017 film brought the Battle of Dunkirk into the spotlight but it had no Indian faces. Did this surprise you?

I had sincerely hoped that he would pick up on the Indian presence at Dunkirk, and honour these men in a way that is long overdue. I was disappointed when I saw the absence of Indians, but not really surprised. In the 80 years since Dunkirk, nobody else had picked up on them, so why should Nolan? He was telling the big story through three particular focuses. I think the challenge now is for a filmmaker with South Asian heritage to make the K6 film.

Why the lapse in Britain’s public memory of the Indian contingent of World War II?

It’s a combination of factors. A shift in public mood immediately after the war towards reconstruction and away from the empire. A process of reframing the war into something smaller and less global, with a focus on key events like D-Day, Dunkirk and the Blitz. As the generations who saw them marching in the streets and training on the mountains died, there has been nobody there to guard their memory, especially as nobody in South Asia has been there to champion them either.

How big was the British Indian Army during World War II?

There were 2.5 million men and 11,500 women. During my research, I was honoured to meet four of them. Some men wept when they saw my photos of their relatives’ graves.

What were the backgrounds of the men of Force K6 like?

Incredibly varied. Some of them were highly educated, from the top drawer of Punjabi society. Some were illiterate. Many were from ordinary farming families on the Potohar plateau. Although the vast majority were Muslims, there were several Sikhs, and their accountant was a Hindu from Lahore. There were also many tradesmen, who had skills like leatherwork or carpentry that were needed in support. There were cooks who spent all day making chapatis, grinding spices and cooking meat. There were sweepers, whose job was to clean up after men and animals. One of them was in the company hockey team.

Did they encounter racism?

Generally they were welcomed warmly in France and Britain. There was one incident of racism that I’ve found, when they were asked to leave a swimming pool in Abergavenny. In this case, the secretary of the swimming club protested in their favour. I’m sure there were other occasions when people whispered behind their hands but to some extent, I think the normal rules were suspended during the war. Arguably Britain’s racism then was more overt but also less widespread.

How did these young Muslim men navigate food, language and friendship in 1940s Europe?

With smiles, with laughter. By making friends with children, by learning. By sharing chapatis and raisins, and by falling in love. I think it was not difficult for them.

Tell us more about the only Indian officer on the beach at Dunkirk, Major Mohammed Akbar Khan.

Ah what a man! Joined the army before the great war as a teenager. Fought in Mesopotamia with the cavalry. Captured by the Turks and escaped. In 1919, he was part of the very first group of Indians to be trained as officers at Indore — together with Field Marshal Cariappa. Rose through the ranks between the wars and earned an MBE. Posted with K6, he was the only Indian officer on the beach at Dunkirk. Spent about a year in Britain during which time he met the King and Queen and had his portrait painted by an official war artist (that portrait will be on permanent display in London’s Imperial War Museum later this year). Returned to India and was promoted. In 1947, he was the seniormost officer in the Pakistan Army, as major-general. He retired soon after and lived with his large family in Karachi.

Why is it crucial to recover forgotten history and in particular, history of South Asia’s contributions during World War II?

There is a tendency in the UK and elsewhere to see it through a very narrow prism. I think we need to remember that the defeat of fascism — the great fight of my parents’ generation — was a multinational one. The efforts of men and women from South Asia were crucial and need to be understood, taught and learnt.

In the face of exclusivist politics, Brexit and Islamophobia, can retelling stories of South Asian military history change minds?

I hope so! I wrote this book because it’s a great story that’s long overdue for telling, but also because I want to help tackle small-mindedness and bigotry.

The US Army Air Force (USAAF) in India

Crash of C-109 aircraft at Bishmaknagar (Lower Dibang Valley)

DNA Tech Helped Identify Turner’s Remains In Sept

First Lieutenant Allen R Turner of the US Army Air Forces died in an aircraft crash in a remote part of Arunachal Pradesh during World War II.

Tuner, who was the pilot of the ill-fated aircraft, was flying a C-109 aircraft from Assam’s Jorhat to Hsin-Ching in China along with three other soldiers when they crashed in the Himalayas in Arunachal Pradesh on July 17, 1945. All of them were declared deceased a year later after an extensive search effort failed to locate the crash site.

The flight engineer was Joseph I Natvick.

USAAF records say the aircraft’s last position was reported over Pathalipam in Lakhimpur, Assam. “Turner, a member of the 1330th Army Air Force Base Unit, Air Transport Command, was hauling fuel, food and other supplies when his plane went missing over the massive mountain range, nicknamed the Hump, which is infamous for air crashes,” said Jeannette Gray, a mortuary affairs officer at the Department of the Army.

As the records say the aircraft crew had never reported any mechanical trouble, it was suspected that the aircraft had exploded in mid-air. Over 60 years later, an independent investigator, Clayton Kuhles, discovered the crash site at Bishmaknagarin Lower Dibang Valley district, in 2007.

After the US government negotiated with India, the DPAA conducted field activities in Arunachal in 2016 in search of the personnel and found some evidence which was examined by a joint forensic review committee comprising DPAA and Anthropological Survey of India members. The committee determined that the evidence was possibly correlated to US WWII service members who were unaccounted for and recommended that the remains and other material evidence be transported to a DPAA laboratory for further analysis. One set of remains was identified to be of co-pilot 1Lt Frederick W Langhorst. In September, Turner and Natvick were accounted for. However, another member of the same crew, Corporal Robert McAdoo, is still unaccounted for.

After 73 years, the remains of First Lieutenant Allen R Turner and Joseph I Natvick were identified through DNA testing in September 2018.

1944: crash in Sapekhati (Assam)=

Parth Shastri, March 17, 2025: The Times of India

It was the summer of 1944, during World War-II. A B-29 Superfortress airplane, part of US armed forces’ 444th Bombardment Group (very heavy), was returning to its base after a bombing raid on the Imperial Iron and Steel Works at Yawata, Kyushu Island, in Japan. The airplane crashed in the rice fields of Sapekhati, today’s Assam, killing all 11 crew members aboard. US teams visited the site after the war, but could recover remains of only seven soldiers. Eighty years later, search for the other four resumed, and search teams managed to find the remains of three.

The three soldiers have been identified as Flight Officer Chester L Rinke, 33, of Marquette, Michigan; Second lieutenant Walter B Miklosh, 21, of Chicago, Illinois; and Sargent Donal C Aiken, 33, of Everett, Washington. They were part of the bombardment mission and died in the airplane crash. Officials associated with the process said the remains will be sent to the US with due procedure.

The search was a joint effort by Gandhinagar-based National Forensic Sciences University (NFSU) and USbased University of Nebraska- Lincoln (UNL), as part of a tripartite agreement with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) of the United States. The teams visited the site in 2022-23 and collected a large cache of samples, including human remains and material evidence like buttons, boot fragments, identification tags, parachute fragments, coins, and survival compass backing. A recent analysis of the samples confirmed identity of the three soldiers.

Gargi Jani, project lead, NFSU, said, “Standard archaeological methods were used to excavate the site of the crash and its periphery. However, since the sediments were saturated with water, a wetscreening operation was used to force water through a series of pumps and tubes and force the mud through 6mm mesh screens to remove the mud and find any small piece of evidence.” A stepped excavation method was used as a safety measure to avoid collapse as trenches were often over 3 metres deep, she said. The DPAA website mentioned the identification was carried out based on material and anthropological evidence along with techniques such as ‘mtDNA’, ‘YSTR’, analysis by scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System.

See also

World War II and India

and many more...