William Shakespeare

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

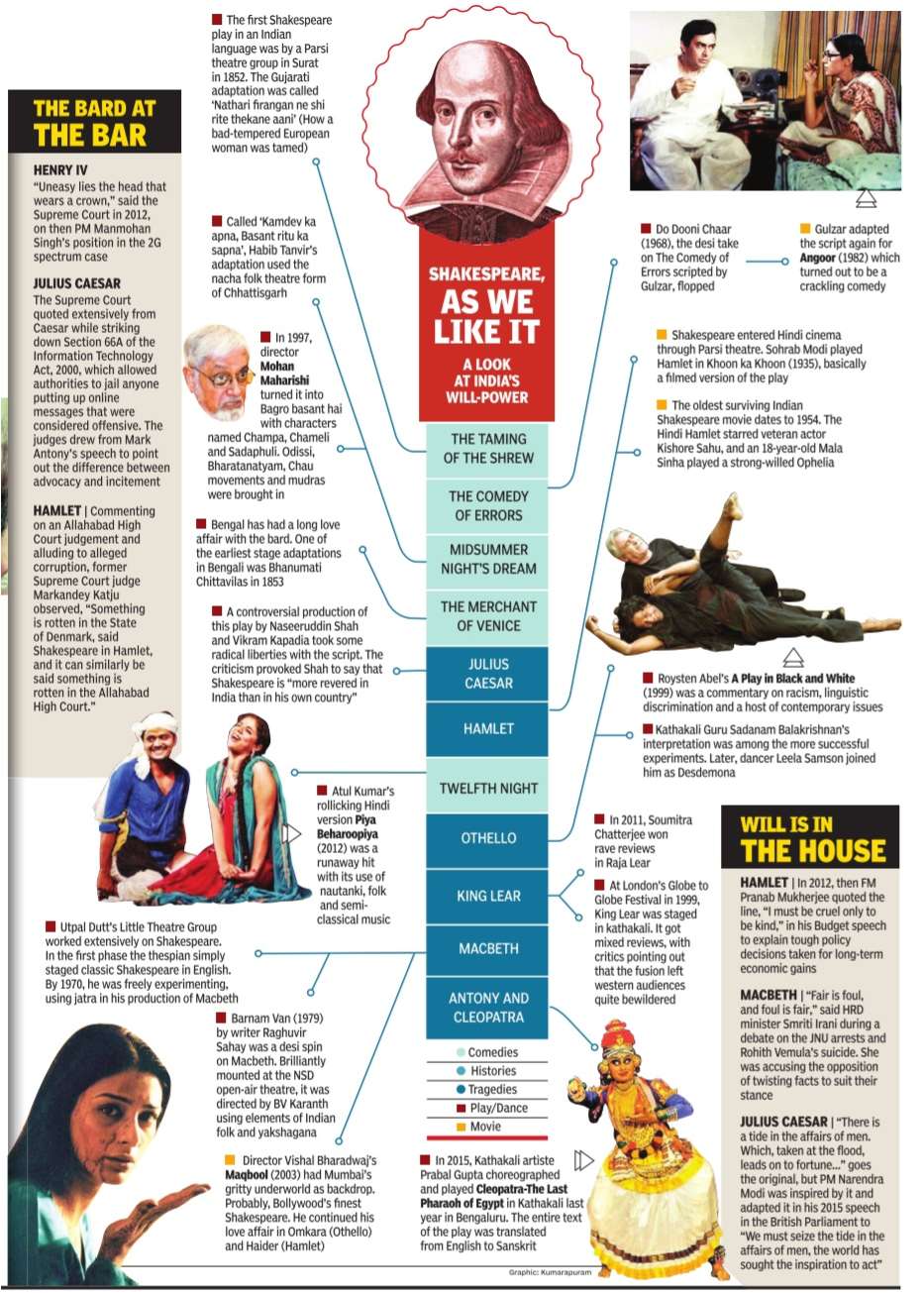

The bard

The Times of India, April 17, 2016

Hona, ki nahin hona, yehi to mamla hain.' It's a line that Anurag Kashyap could easily have had Nawazuddin Siddiqui utter as Faizal Khan in a key scene in Gangs of Wasseypur. The line is primal, infused with depth, and comes with a dramatic oomph that sinks it into the deep end of the pop cultural pool.The way Amitabh's `Mein aaj bhi pheke hue paise nahin uthata' from Zanjeer, or Amjad's `Yeh haath humko de de, Thakur!' from Sholay , or Bogart's `We'll always have Paris' does.

And yet, there we have it. The iconic line in its original avatar uttered by a choleric member of the Danish royal family -`To be, or not to be, that is the question -was written by an Englishman some 400 years ago.

Yes, it's in English. Yes, we associate it with school plays, school textbooks and, most with school plays, school textbooks and harrowingly , with folks quoting lines from Shakespeare with the express purpose of telling us that they `know their Shakespeare'. But behind all these lie acres of lines -dialogues, as they say in the industry -dealing with every aspect of the Human Condition: love, fear, guilt, lust, power, hurt, confusion, laughter, and variations thereof that Guru Dutts and Manmohan Desais have made a name and livelihood out of.

Four hundred years since the death of William Shakespeare on April 23, 1616, he remains as universal as he remains iconic. But are his works alive for us here in 2016? Do they speak to us with the kind of force and accuracy that the most potent films do? And most importantly, are they meant to? Hell, yes, they are meant to be. Shakespeare, it is always good to remember, was working in the 16th century English equivalent of HollywoodBollywood. As an actor, writer and part-owner of the `playing company', Lord Chamberlain's Men, he was the Salim-Javed-Quentin Tarantino of his time and space.

He wrote plays not for your family edition of `The Collected Works of Shakespeare'. He wrote plays for the box office the way SRK plays for it.

He doled out bawdy slapstick for the frontstallers -the raucous `groundlings' at the Globe Theatre -philosophical enquiries for the more high-minded, tragedies that would make Devdas stay sober, comedies that would make Woody Allen less neurotic, and `adult scenes' that one could only enjoy if you downloaded them.

Romeo and Juliet was a trailblazing hit not because it was a damn fine romance. It was a super-hit because it turned the spotlight of a holds-barred love story and doused it in that other pop ingredient: the tearjerker tragedy that Salim and Anarkali in Mughale-Azam and every young couple negotiating with khap or family will immediately recognise at a stolen noon show rendezvous.

And it is impossible for anyone not to recognise the corrosive power of power, and the mechanics of political powerplay, of PGrated plays like Coriolanus, Richard III -and more fantastically in The Tempest and King Lear -in today's Golden Age of Englishlanguage television as one addictively follows shows like The House of Cards, The Game of Thrones, Madmen and The Sopranos.

One can rattle off one iconic line after the other -lines that Shakespeare not only invented, but also lines with which he made inventions in the English language itself (`with bated breath', The Merchant of Venice; `break the ice', The Taming of the Shrew; `fancy-free', A Midsummer Night's Dream'; `the green-eyed monster'; Othello, `wild-goose chase' from Romeo and Juliet).

But that is what Shakespeare has brought to one language: English. There is much more that his works hold, like deep shale waiting to be extracted and extricated out of the ivory towers occupied by Shakespeare-walas.

There have been countless adaptations of Shakespeare's plays in every possible human language -and non-human too, if one considers Nick Nicholas' and Andrew Strader's Klingon adaptation of Hamlet, with the prince's soliloquy rendered perfectly in the opening line `taH pagh taHbe'.

But for the true force of Shakespeare to come through -in any language and whether rendered in movies, text, or on the stage -his drama has to be unfurled with all its sweat, swagger and, yes, item numbers.

Vishal Bhardwaj's Maqbool and Omkara, the 2004 and 2006 adaptations of Macbeth and Othello set in gangland Mumbai and in the badlands of western Uttar Pradesh respectively, captured this Shakespearean essence. As did his 2014 rendition of Hamlet in Haider set in mid-90s Kashmir.(Rituparno Ghosh's Amitabh Bachchanstarring 2007 film, The Last Lear, was a stilted disaster.) Even `Bollywood', with its genius for `dialogues', is naturally inclined to the technicoloured and choreographed world of Shakespeare than the rarefied Shakesperean universe that many of us are more familiar with.

It is our good fortune that there is no political entity desperate to appropriate the patron saint of human drama as `one of their own', as is wont these days. But let it also be our good fortune that we do truly appropriate the works of Will Shakespeare from another language, country and time.

If there is one culture that can dive naturally into his bubbling world of drama, melodrama, song and dance, violence, deceit, chaos, lust, disappointment, `nonvegetarian' jokes.. it is ours. As the man would have said before his next Friday release, `Readiness hi sab kuchh, bhai.'