Vodafone in India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Vodafone in India

2007-14

From: September 26, 2020: The Times of India

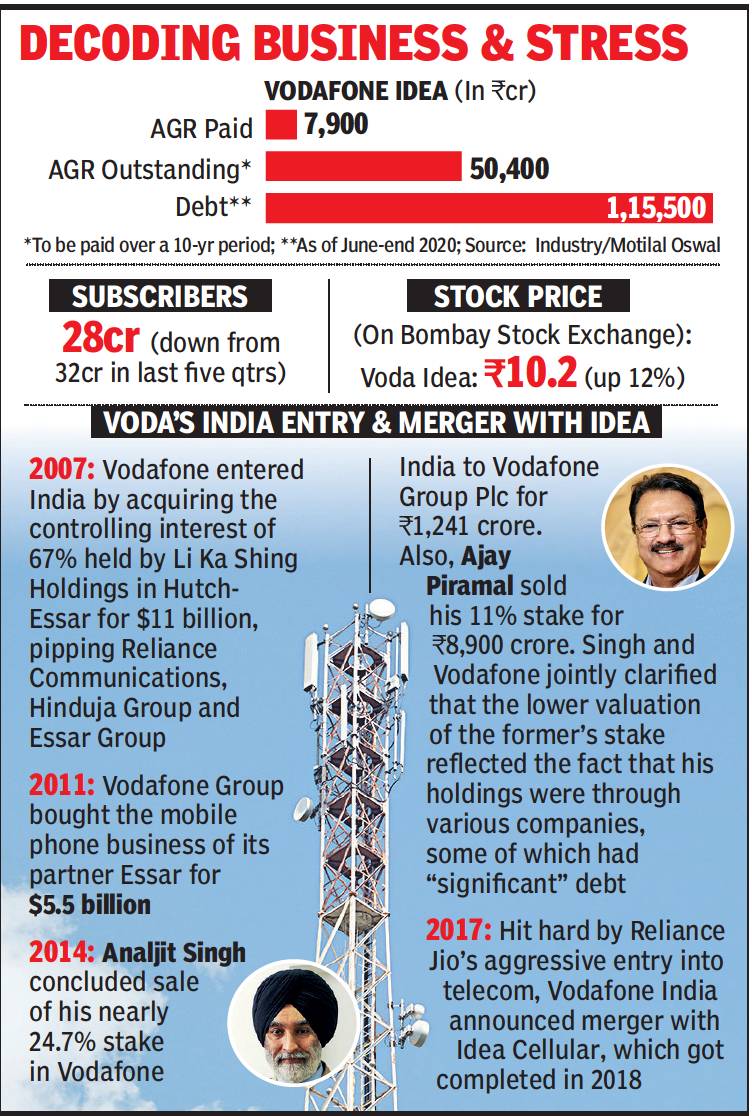

See graphic:

Vodafone in India: 2007-14

2012: Vodafone wins in Supreme Court

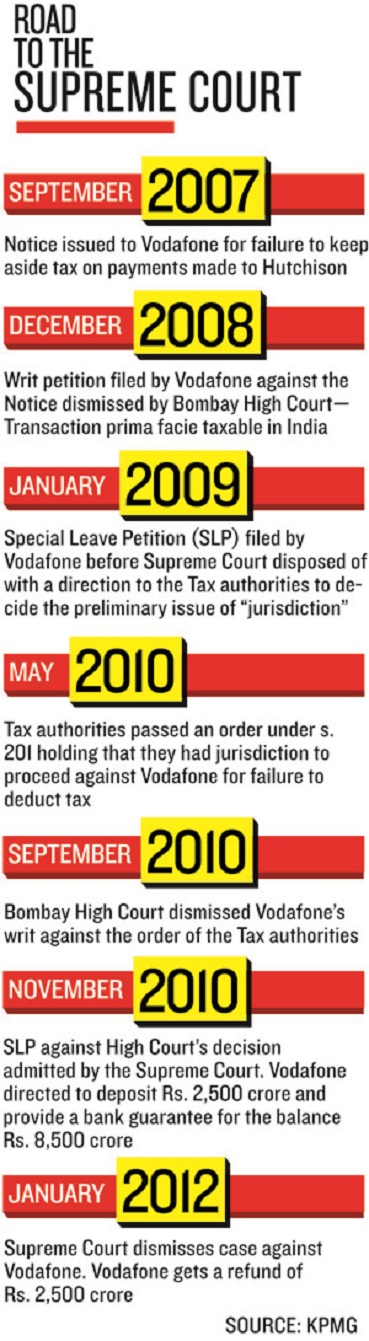

KPMG- Forbes India

KPMG- Forbes India

The apex court says Indian tax authorities have no jurisdiction on overseas transactions.

The Supreme Court ruled in favour of British telecom major Vodafone in the biggest tax dispute case in Indian corporate history. The company had challenged the Bombay High Court order asking it to pay around Rs 11,000 crore (2.4 bn dollars) to the income tax (I-T) department for an acquisition in the country.

The apex court said Indian tax authorities have no jurisdiction on overseas transactions.

In 2007, when Vodafone took over Hutchison International, the I-T department had slapped a tax notice for non-payment of dues saying the company had acquired assets in the country as Vodafone deal involved entities based in Britain, the Netherlands, Cayman Islands, Mauritis and Hong Kong.

In this case, Hong Kong-based Hutchison International sold its shares in the Indian company through a company based in an offshore destination.

The inside story of the courtroom battle

(Additional reporting by Bharat Bhagnani & Shishir Prasad)

How Vodafone won the tax case: The inside story of the courtroom battle

The court hearings had gone on through all of August. On September 8, 2010, the Bombay High Court was packed to the rafters with newspaper reporters of all hues. There was a battery of lawyers representing the Government of India and telecom giant Vodafone. There were two judges who had been hearing the famous Vodafone tax case: D.Y. Chandrachud and J.P. Devadhar. Though Devadhar was in Nagpur that day, he was ‘virtually’ present through a video link. Vodafone’s tax spearhead Desmond Webb was there.

“Most reporters who had covered the hearing passed around early congratulations to us. They believed our counsels Harish Salve and Abhishek Manu Singhvi had done enough for the Bombay High Court to rule in our favour,” says a former Vodafone employee who was present in the courtroom.

As the judgement began to be read out, there was some buoyancy in the Vodafone camp. The two judges did not think that Vodafone’s purchase of Hutch’s business was done in a manner to avoid taxes. The two judges also said that the shares that gave Vodafone control over Hutch’s telecom business in India were registered outside the country—in Cayman Islands. And then they turned their attention to the specific issue on which they were supposed to pass a judgement—that Indian tax authorities simply did not have any jurisdiction, any basis to even analyse the transaction. The judges said while they were convinced that Vodafone’s transactions were genuine, they were also quite sure that such a complex transaction needed more investigation. This was Vodafone’s Javed Miandad moment. The match was lost on the last ball.

“We could not have been more disappointed. Three years had passed by and we had provided so much information and yet the issue was not settled,” says a Vodafone executive.

The two people who were slugging it out—Mohan Parasaran on the side of the government and against him Harish Salve who was representing Vodafone—were both not there in the court that day. That would have to wait for another day.

Perhaps no case in corporate history has evoked as much interest as the Vodafone tax case. For all the right reasons, one might add. For the first time in the history of free India, the Indian tax authorities were going after a fat-pursed multinational that had bought a business in India.

In 2006, the Indian mobile telecom market was growing very rapidly. Every month more than 10 million subscribers were signing up to own a mobile connection. If you were a global telecom company, you had to have a piece of the Indian telecom action and you had to buy one of the top firms because in this industry bigger players make more money.

The top dogs in the Indian market then were Bharti Airtel, Reliance Communications and Hutchison Essar. The former two were not selling. Hutchison was owned by the Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-Shing and he was interested in exiting the business. Vodafone, the British telecom company, wanted to come into India. But others too wanted to buy Hutch to increase their market share. Reliance Communications definitely made a play for the firm. It was a tight finish and on February 12, 2007, Li Ka-Shing accepted Vodafone’s bid and Hutch was sold. That should have been the end of the matter. As things turned out, the sale was just the beginning.

In September 2007, the tax authorities sent a letter to Vodafone. It had just one question for the British firm. Why hadn’t it kept aside money due to the Indian Income Tax Department? The first reaction in Vodafone headquarters was: “Huh? What taxes?” Indian tax authorities were only too happy to point out that while Vodafone and Hutchison Whampoa had done the deal outside India, in effect it involved the sale of an Indian asset—Hutchison Essar India Limited. Since Li Ka-Shing had made such a handsome profit on the sale, he should have given Vodafone the capital gains tax due on the transaction to keep aside for the Indian taxman.

“The only thing that the senior management at Vodafone thought is ‘this is absurd!’ There is no precedent for this anywhere in the world. Why is the Income Tax Department coming after us?” says a Vodafone senior manager.

What they didn’t know then was that one of Income Tax Department’s finest minds, Girish Dave, had been thinking about how India could benefit from mergers and acquisitions activity that involved an India angle. Dave retired from the department in 2010, but he was the director of international taxation at Mumbai between 2005 and 2009. That was when he decided to bell the offshore cat.

More surprise was to follow. In the Union Budget of 2008-2009, the government gave a new meaning to something called “assessee in default”. Normally, this rule would apply if someone had collected taxes on behalf of the government, but forgot to deposit it with the government. For example, a company that had deducted income tax from its employees’ pay, but did not give the government that money. That was “assessee in default” before 2008. But after 2008, even if you were supposed to collect taxes on behalf of the government and had not collected it, you became “an assessee in default”. And this change would become effective from June 2002—five years before the Vodafone deal happened.

Sniggering chartered accountants called it the Finance Ministry’s “Vodafone Amendment”.

Vodafone decided to play the game with all the flair of Alistair Cook. They took the issue straight to the court. That’s when Girish Dave’s court alter-ego came into being: Mohan Parasaran, the additional solicitor general, Supreme Court of India. This sharp lawyer practiced in the Madras High Court in various branches of law and was also a professor of law at Presidency College. He became what Vodafone claimed about its network: Whichever court the company went to, Parasaran would follow them.

__PAGEBREAK__

And to courts they went, many times over (see timeline). In September 2008, Iqbal Chagla was Vodafone’s counsel but he couldn’t get the courts to keep the tax authorities at bay. In the January 2009 hearings Vodafone had Fali Nariman represent it in the Supreme Court, which directed the case back to the Bombay High Court. Through 2008 and 2009, the courts maintained that, on the face of it, the Indian tax authorities were well within their right to pursue the case against Vodafone. So Vodafone’s opening gambit that the Indian tax authorities had no jurisdiction over the transaction, failed.

mg_63694_vodafone_280x210.jpg Vodafone then brought in two new counsels for the August 2010 hearings in the Bombay High Court: Harish Salve and Abhishek Manu Singhvi. While Salve could not convince the Bombay High Court to drop the matter he did improve Vodafone’s position. Judges Chandrachud and Devadhar did not find the transaction to be a sham and set up in a manner to avoid taxes.

The final task of improving the positional play of Vodafone would be the task of this boy from Nagpur, who the Nagpurians say is more of a Delhiite now!

If you had to prepare a list of the top 10 lawyers in the country, Harish Salve would easily figure on it. He is described by some as a “legal robot”, which is perhaps a recognition of his methodical execution. Salve has represented most high profile politicians, big business such as Reliance Industries, and even states. He is counsel for Kerala in the Mullaperiyar Dam case.

His father N.K.P. Salve was once a Congress stalwart from Vidarbha, Maharashtra, and also a successful chartered accountant. His firm Salve and Company still exists. Harish Salve grew up in affluence in a bungalow near Mount Road, in Nagpur. By a happy coincidence that house stands right behind Saraf Chambers, which houses the Income Tax Department offices!

Salve studied commerce at G.S. College of Commerce and then just moved across the road to study law at Government Law College. In doing that he followed in the footsteps of his grandfather who was a lawyer and then went to do his chartered accountancy, just like his father. That gives him a formidable preparation to work as a tax lawyer. But more than his education it is his interests that probably make him the lawyer that he is today.

“Harish loves forests; he loves music—both Indian and Western—and he is very down to earth. Even as a child he would never let his friends feel that he was privileged,” says Shashikala Salve Meshram, his paternal aunt. “We were going to his house recently in an auto rickshaw and the driver asked about him and said ‘Harish bhaiyya and I have played cricket together’,” she says.

Throughout his career he has taken up cases that show his sensitivities. He took it upon himself to get the Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act [POTA] charges dropped against the Godhra accused. He also got the Delhi Development Authority [DDA] to stop hacking trees at Delhi’s Siri Fort Complex.

It is perhaps his injustice compass that made him take up the Vodafone case after the Dave-Parasaran duo had made life rather difficult for Vodafone. Salve felt that the stand taken by the Income Tax Department was very counter-intuitive. “Why do you want to tax these companies? For 10 years you allowed them to set up a Mauritius company, and now when they sell upstream the government says this should be taxed. The whole thing sounds very wonky. This is wrong,” he says.

He was approached by Hutch, which was an old client. Initially, there was a difference in the way Hutch and Vodafone perceived the case. But both the firms decided to work together and worry about who would pay the liability at a later date. “So in the first round I think Hutchisson was kept out and Vodafone was unhappy with the result. They dropped the legal team and went to Dutt Menon Dunmorrsett [DMD]. In May 2009, I was approached and they decided to work together and it paid dividends,” he says.

After the setback in the Bombay High Court in 2010, Salve made sure that the preparation was even more thorough for the final showdown in the Supreme Court. At any given time there were 8-14 associates working on the case. These are the ones that were present in court. In terms of the documentation, they prepared 8,000 pages that were filed on the record before the court.

There were 26 volumes of judgements that were submitted. The lawyers had the entire compendium of Income Tax Reports in court that they could pull up at any given time. Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday were the days of the hearing and so these were brought to the court on Monday night and taken back on Thursday evening. The documents which were put in 66 bags took eight car trips every week to take to court.

On admission days, that is Monday and Friday, a senior lawyer like Salve would have about 20 matters. Out of this he would make it to court for say, 15. Then on the final hearing days (Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday) he would have just one matter. So the opportunity cost of this case was huge for him. He gave up everything between August 2 and October 19, 2011, when the case was argued (except in the rare case where he just could not say no to a particular client). He went to London to prepare for the case and was on call 24x7. “I have a flat in Mayfair [to prepare for the case]. I find life very orderly there,” says Salve.

__PAGEBREAK__

mg_63696_vodafone_lawyer_280x210.jpg Harish Salve: Amit Verma; Fereshte Sethna: Manoj Patil for Forbes India

The government (tax authorities) maintained the same line and length that they had done for the past four years. “Amongst the IT Department’s fundamental assertions was that this was a sham and fictitious transaction devised to avoid tax,” says Fereshte Sethna, partner, Dutt Menon Dunmorrsett. That also raised the stakes for the government because it had to prove this as a sham transaction. No mean task given the level of preparation of the judges.

Justices S.H. Kapadia, Swatanter Kumar and K.S. Radhakrishnan were very well prepared. They knew that they were going to be deciding on a seminal tax case. Justice Kapadia himself being very knowledgeable on tax matters would ask a lot of questions. “On a particular occasion, the Bench indicated having researched international tax law material over the Internet, based on which queries were put regarding the position prevalent in Japan. Often, prior to commencing arguments on a given morning, questions from the Bench entailed 30 minutes to an hour. Senior Counsel Harish Salve answered these, before continuing arguments that day,” says Sethna.

Vodafone also made Philip Baker available as an expert witness. He is an internationally recognised authority on tax law and he filed two expert reports. As and when issues arose before the courts, he would provide answers. In effect, he helped the judges understand what tax laws in other jurisdictions are.

Finally, the arguments came down to two basic issues. The first issue was about whether Hutch sold assets like telecom licences, brand and towers in India as opposed to a sale of shares. The tax authorities maintained that while Vodafone gained control over Hutch’s India business when it bought a Cayman Islands registered company called CGP, all the value of CGP came because of its control over licences, brand, towers and infrastructure owned by the India business. The Supreme Court Justices were quite unequivocal in saying that a share is not distinct from an asset. Once you own the share the asset automatically comes to you.

That brought into play the next line of defence from the tax authorities who said that the location of all the value of the share was in India. The Supreme Court Justices said that the share that gave control to Vodafone was CGP’s and that was located outside India. The tax authorities said something to this effect: “But that company CGP has nothing. It is just a shell company.”

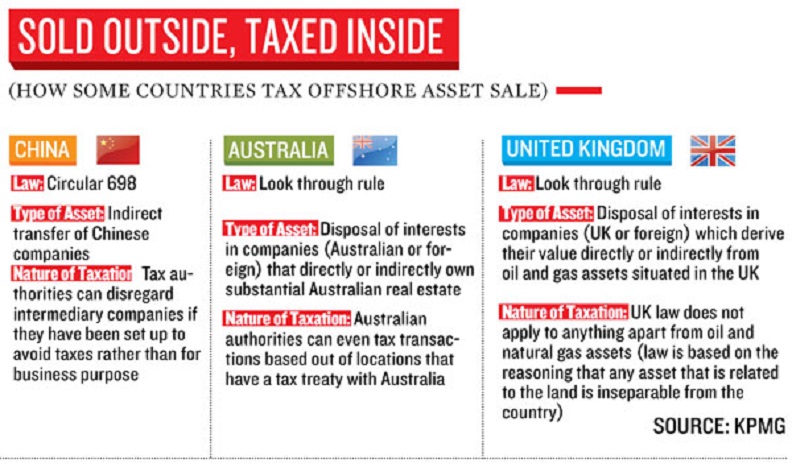

To which the justices said—and this is important—that the law of the land does not say anything explicit about that. They said that the courts were here to interpret the law, not make it. “It is for a country to decide what it wants to tax. Under the DTC [Direct Tax Code] there is a specific provision that if you acquire upper tier shares and 50 percent of the value of the transaction is in India, then it is liable to be taxed on a pro rata basis. But it isn’t a law as yet,” says Dinesh Kanabar, deputy chief executive officer and chairman tax, KPMG (India). China, UK, and Australia do tax such transactions (see graphic on page 50). Salve is quite candid about the letter of the law. “If the Chinese income tax officer said that this was not genuine tax planning, Vodafone would have had to reach out for their cheque book,” he says.

But India is not China. Vodafone and Hutch created a business structure based on existing India laws. The final word on the matter can well be that of Justice K.S. Radhakrishnan who said: “The Revenue has failed to establish both the tests, Resident Test as well the Source Test.”

mg_63698_vodafone_tax_280x210.jpg So, on January 20, 2012, Salve and Parasaran were both in the Supreme Court to hear something that consumed a good part of their time. When the judgement was announced, Justice Kapadia came into the courtroom with two sheets of paper at 1.15 p.m. on January 20 and started reading from the paper.

It took him about 15 minutes to read and the team was on tenterhooks till the 12th minute as they had seen the Bombay HC order where the last bit of the judgement had gone against them.

It was only after the 12th minute when Justice Kapadia came to the operative portion of the judgement that they knew they could celebrate. The Vodafone team was ecstatic! And did Salve celebrate? “No no, I did not. The judgement came at 1.15 p.m., I had rushed to [Delhi] High Court and finished at around 4.30 p.m. and then came back home. When you work very hard for an exam and you do well, you like it,” he says.

Spare a thought for both Dave and Parasaran who put in a great effort. Salve does, that’s for sure. “The tax authorities had prepared well and argued well. It was not one of the cases where it was open and shut on any issue. In fact, when I came out of the court, I said it could go either way. If you are a good lawyer, you are a salesman of ideas,” says Salve.

For Dave, this was an innings well played. “The Solicitor General [Rohinton Nariman] who argued the case for the Revenue, did an excellent, unparalleled job, put the issues before Hon’ble Court in an inimitable way, but missed only in adopting the strategy employed by the other side who went on repeating to the extent of nausea in repeating, repeating and repeating way on issues like (1) look-through provisions,(2) FDI & (3) the way multinationals operate businesses globally.”

Parasaran, who almost won the day for the tax authorities, says: “I think the Supreme Court also went by how the case would affect FDI and investor confidence. This was one of the main factors I think. But in my perception no foreign investor will run away from India as everybody can make a profit here. Our country did not survive just because of FDI.”

According to Parasaran, both sides presented their case before the Supreme Court in an exceptional manner. “Salve was able to present the case from a macro as well as micro perspective and argued extensively.”

None of these legal eagles expect the matter to be raked up again. The zoozoos can cackle in comfort.

The issue, as seen in 2012

Prashant Bhushan’s view

(The author is a Supreme Court advocate)

In the Vodafone case, the Supreme Court has again made a wrong call on tax avoidance, setting a precedent that jeopardises thousands of crores of potential revenue for the exchequer.

Tax avoidance through artificial devices — holding companies, subsidiaries, treaty shopping and selling valuable properties indirectly by entering into a maze of framework agreements — has become a very lucrative industry today.

A large part of the income of the ‘Big 5' accountancy and consultancy firms derives from tax avoidance schemes which flourish in the name of tax planning. Their legality has agitated courts in India and abroad for a long time. In 1985, a 5-judge bench of the Supreme Court in the McDowell case settled the question decisively, observing:

“In that very country where the phrase ‘tax avoidance' originated, the judicial attitude towards [it] has changed and the smile, cynical or even affectionate though it might have been at one time, has now frozen into a deep frown. The courts are now concerning themselves not merely with the genuineness of a transaction, but with [its] intended effect for fiscal purposes. No one can now get away with a tax avoidance project with the mere statement that there is nothing illegal about it. In our view, the proper way to construe a taxing statute, while considering a device to avoid tax is … to ask … whether the transaction is a device to avoid tax, and whether the transaction is such that the judicial process may accord its approval to it.”

“It is neither fair not desirable to expect the legislature to … take care of every device and scheme to avoid taxation,” the ruling added. “It is up to the Court … to determine the nature of the new and sophisticated legal devices to avoid tax ... expose [them] for what they really are and refuse to give judicial benediction.”

‘Legitimate tax planning'

Despite such a clear pronouncement, two recent judgments of smaller Supreme Court benches have gone back to calling artificial tax avoidance devices “legitimate tax planning”.

Though the Income Tax Act obliges even non-residents to pay tax on incomes earned in India, many foreign institutional investors avoided paying taxes citing the Double Taxation Treaty with Mauritius. This treaty says a company will be taxed only in the country where it is domiciled. All these FIIs, though based in other countries and operating exclusively in India, claimed Mauritian domicile by virtue of being registered there under the Mauritius Offshore Business Activities Act (MOBA). Companies registered under MOBA are not allowed to acquire property, invest or conduct business in Mauritius.

Yet these ‘Post Box Companies' claimed to be domiciled there and the I-T department allowed them to get away with claiming the benefits of the treaty for many years. Given the benign attitude of the Indian tax authorities and the fact that there was no capital gains tax and virtually no tax at all on these companies in Mauritius, most FIIs and most of the foreign investment in India, by 2000, came to be routed through Mauritius.

The party finally ended when a proactive tax officer tried to stop this blatant evasion. Relying on McDowell, he lifted the corporate veil of MOBA companies to determine their place of management and actual place of residence. Since this happened to be in different countries in Europe or North America, the relevant Double Tax Avoidance treaty became the one between India and that country. All these treaties provided for capital gains to be taxed where the gains had accrued. Since the gains accrued in India, he levied capital gains tax on these FIIs.

The CBDT circular

Responding to the FIIs' distress calls, the then Finance Minister, Yashwant Sinha, got the Central Board of Direct Taxes to issue a circular stating that once a company had obtained a tax residence certificate from Mauritius, it would not be taxed in India.

The CBDT's circular was challenged in the Delhi High Court by Azadi Bachao Andolan and a retired Income Tax Commissioner. The petitioners also pleaded that the government be directed to amend the treaty with Mauritius since it had become a tax haven. The High Court allowed the writ petitions and quashed the CBDT circular, holding it violative of the I-T Act.

The government appealed, telling the Supreme Court that its circular — which effectively offered a tax holiday to FIIs — was needed to attract foreign investment. The petitioners responded that tax exemptions could only be granted by Parliament, either by amending the Income Tax Act or by the Budget passed each year, and not by the government in the guise of such a circular. However, a two judge bench in 2003 called this device an act of legitimate tax planning which could be promoted by the government to attract foreign investment, defied the Constitution bench judgment in McDowell and set aside the Delhi High Court judgment.

In the Vodafone tax case, which was heard by a 3-judge bench of the Supreme Court, the court had the opportunity to correct the transgression of the McDowell principle in the Mauritius case. In 2007, Hutchinson Telecom International (HTIL), which owned 67 per cent of Hutch Essar Limited (HEL), an Indian telecom company, sold its holding to Vodafone International (VIH BV). Both companies announced that Hutchinson had sold, and Vodafone had bought, 67 per cent of the shares and interest in the Indian company for over $11 billion.

Section 9(1) of the Income Tax Act says incomes which shall be deemed to accrue or arise in India include “all income accruing or arising, whether directly or indirectly, through … the transfer of a capital asset situated in India.”

Vodafone's claim

Since the transfer of the Indian telecom firm's shares and assets to Vodafone had led to capital gains for Hutch, the IT department demanded capital gains tax from Vodafone, which was liable to withhold this tax from the amount they paid Hutch. Vodafone claimed the transaction was not liable to tax since it was achieved by transferring the shares of a Cayman Island-based holding company and did not involve the transfer of a capital asset situated in India. The High Court rejected this contention by holding:

“The facts clearly establish that it would be simplistic to assume the entire transaction between HTIL and VIH BV was fulfilled merely upon the transfer of a single share of CGP in the Cayman Islands. The commercial and business understanding between the parties postulated that what was being transferred … was the controlling interest in HEL. HTIL had, through its investments in HEL, carried on operations in India which HTIL in its annual report of 2007 represented to be the Indian mobile telecommunication operations. The transaction between HTIL and VIH BV was structured so as to achieve the object of discontinuing the operations of HTIL in relation to the Indian mobile telecommunication operations by transferring the rights and entitlements of HTIL to VIH BV. HEL was at all times intended to be the target company and a transfer of the controlling interest in HEL was the purpose which was achieved by the transaction.

“Ernst and Young who carried out due diligence of the telecommunications business carried on by HEL and its subsidiaries made the following disclosure in its report:

“The target structure now also includes a Cayman company, CGP Investments (Holdings) Ltd. CGP Investments (Holdings) Ltd was not originally within the target group. After our due diligence had commenced the seller proposed that CGP Investments (Holdings) Ltd should be added to the target group …”

The due diligence report emphasizes that the object and intent of the parties was to achieve the transfer of control over HEL and the transfer of the solitary share of CGP, a Cayman Islands company, was put into place at the behest of HTIL, subsequently as a mode of effectuating the goal.”

Following McDowell, where the Supreme Court had decisively frowned upon tax avoidance schemes, the High Court rejected Vodafone's contention that this transaction was not liable to tax. But in appeal, a Supreme Court bench of 3 judges headed by Chief Justice Kapadia accepted Vodafone's claim that the capital gain had arisen only from the transfer of the single share in the Cayman Island company and had nothing to do with the transfer of any asset situated in India.

Despite the fact that the entire object and purpose of the transaction between Hutch and Vodafone was to transfer the shares, assets and control of the Indian telecom company to Vodafone, the Supreme Court declared in January 2012 that the transaction has nothing to do with the transfer of any asset in India!

With such welcoming winks towards tax avoidance devices, it is unlikely that any foreign company would be called upon to pay tax or at least capital gains tax in future in India. Thousands of crores of tax revenue, and the future attitude of the courts towards innovative tax avoidance devices, will be shaped by these two judgments.

The Vodafone case is in the lineage of the Mauritius case inasmuch as both encourage tax avoidance devices ostensibly to attract foreign investment. The 2G judgment of the Supreme Court cancelling 122 telecom licences granted four years earlier, in sharp contrast, enforces the constitutional principle of equality and non-arbitrariness. The proponents of FDI are groaning that this will stem the flow of investment. Honest foreign companies should not be deterred by this judgment, which strikes a blow against crony capitalism. But even if FDI becomes a casualty in the enforcement of the rule of law, so be it.

Our courts must send a clear signal that India is not a banana republic where foreign companies can be invited to loot our resources and even avoid paying taxes on their windfall gains from the sale of those resources.

Arvind P. Datar’s critique

(The author is a senior lawyer of the Madras High Court.)

The demand for tax in the Vodafone case was a result of failing to understand the difference between the sale of shares in a company and the sale of assets of that company.

The article “ >Capital gains, everyone else loses” by Prashant Bhushan (February 23, 20120) gives a wrong impression that the Vodafone case has resulted in a loss of several thousands to the exchequer and the Supreme Court has blessed a massive tax evasion scam. The truth is that the demand made by the Income Tax Department was wholly unsustainable. If the Vodafone case had a tax implication of just Rs.10 crore, the case would have been over before the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal itself and there would not even be a single comment in the press or electronic media. But the law does not change if the tax demand is of a large amount.

Shares and assets

The demand for tax in the Vodafone case was a result of failing to understand the difference between the sale of shares in a company and the sale of assets of that company. It is an elementary principle of company law that ownership of shares in a company does not mean ownership of the assets of the company. Thus, an individual who owns 45 per cent or 85 per cent of the share capital does not own 45 per cent or 85 per cent of that company's assets. The assets belong to that company which is a separate legal entity. In the Vodafone case, 51 per cent of Hutchison Essar Ltd. (HEL) was directly owned by the Hutchison group of Hong Kong through a multiple layer of companies and ultimately by a company incorporated in the Cayman Islands. This was not the result of any devious tax planning scheme but the consequences of the growth of Hutchison Essar Ltd. by acquiring several telecom companies over the years. Hutchison International decided to exit its Indian operations and a public announcement was made to this effect.

Vodafone was the successful buyer of the share of the Cayman Island company for $11-billion. Consequently, by purchasing one share of the Cayman Island company, Vodafone came to own 51 per cent of share capital of HEL. The transfer of shares of one non-resident company (Hutchison) to another non-resident company (Vodafone) did not result in the transfer of any asset of HEL in India. All the telecom licences and assets continued to belong to HEL or its subsidiaries.

The absurdity of the demand in the Vodafone case can be explained by two simple illustrations. Hyundai Motors India Ltd. is a wholly owned subsidiary of the parent Hyundai company in Korea. The Indian subsidiary has a large factory near Chennai and perhaps owns several other assets. If, for example, Samsung purchases 65 per cent of the share capital of the parent Korean company in Seoul can it be argued that Samsung has automatically purchased 67 per cent of the factory at Chennai? Consequently, can it be said that the sale of shares in Korea resulted in a capital gain in India which requires Samsung to deduct tax at source under the Indian Income Tax Act, 1961? Under Section 9(1)(i) of our Act, there is liability to tax only if there is a transfer of a capital asset in India. In this illustration, the capital asset that is transferred was the share in Korea and there is no transfer of assets in India. The Indian subsidiary continues to exist and continues to own the factory as well as other assets.

The absurdity can also be seen by a domestic illustration. Tata Motors Ltd. has its headquarters at Mumbai and factories at Jamshedpur and Pune. If another Indian group purchases 67 per cent of the shares of Tata Motors Ltd., the transfer of shares takes place in Mumbai which is the registered office of that company. Can any one say that there is a corresponding transfer of 67 per cent of its factory, lands and buildings at Pune and Jamshedpur as well? Can the local stamp authorities in Jharkhand and Maharastra demand stamp duty on the ground that there is also a transfer of underlying assets? It is elementary that what has been sold is only 67 per cent of the paid-up share capital of Tata Motors Ltd.

The assets of that company remain with that company and do not get transferred. The sale of the shares of Tata Motors cannot and does not result in the transfer of its “underlying assets.”

This is exactly what happened in Vodafone. The shares owned by Hutchison were sold to Vodafone indirectly purchasing 51 per cent of the share capital of Hutchison Essar Ltd., a company registered in Mumbai. Not a single asset of this Mumbai based company was transferred either in India or abroad. Indeed, there would be no transfer of any asset in India.

This is also exactly how several international transactions are concluded. Vodafone was not the first case where transfer of shares between non-resident overseas company resulted in a change in control of an Indian company. But controlling interest is not a capital asset; it is the consequence of the transfer of shares. The demand made by the Income Tax Department in the Vodafone case was thus contrary to elementary principles of company and tax law.

The McDowell case

Prashant Bhushan makes detailed reference to the decision of a five-judge bench in this case. The tragedy is that the observations in the McDowell case were wholly unnecessary. The only issue there was whether the excise duty directly paid by the purchasers of liquor could be included for the levy of sales tax. There was absolutely no need to get into the distinction between tax avoidance and tax evasion. The McDowell judgment had blurred the distinction between these two concepts by not correctly following the development on this subject in the United Kingdom. The true principle is that tax avoidance is perfectly legitimate, but tax evasion is not. For example, central excise duty is exempted for units located in Himachal Pradesh. If an assessee sets up his manufacturing unit in the exempted area, he is “avoiding the excise duty” by taking advantage of a lawful scheme. This is tax avoidance and not tax evasion. Similarly, there is no bar in one non-resident company selling its shares to another non-resident company outside the territory of India. The Indian Income Tax Act does not apply to such transactions and such a transaction cannot be treated as tax evasion.

India-Mauritius treaty

There has been severe criticism of the India-Mauritius Treaty and it has been accused of depriving the Indian government of crores of rupees of tax revenue. If there is a policy decision to permit tax exemption for investments through Mauritus, one cannot blame the courts for any potential loss of revenue. The government is fully conscious of the so-called loss of direct tax revenue but these incentives are essential to foreign direct investments. The huge growth in the telecom and other sectors has been substantially done through the Mauritius route. One cannot forget the enormous employment generated by FOI and the substantial increase in excise duty, sales tax and other duties and cesses. To merely harp on loss of income tax is not correct.

In the end, the Supreme Court's decision is absolutely correct and adheres to the fundamental principles of company and tax laws. In the Vodafone case the demand was for capital gains tax which never arose in India. Once the hollowness of the department's claim was exposed, the absence of any liability became clear. One should not look at any judgment with a jaundiced eye and condemn it on the ground that it results in a loss of tax revenue.

The courts merely interpret the law and if a transaction is not liable to Indian income tax, one must graciously accept the result.

Prashant Bhushan responds

Prashant Bhushan responds| MARCH 02, 2012, UPDATED: MARCH 09, 2012 | | The Hindu

(Prashant Bhushan is a Senior Advocate and member of the civil society team that drafted the Jan Lokpal Bill.)

Mr. Datar's >response to my criticism of the Supreme Court's Vodafone judgment is precisely Vodafone's lawyers' arguments before the courts, which is natural since he was one of them. Though the stated object and purpose of the sale purchase agreement between Hutch and Vodafone was to transfer the shares, assets and control of the Indian Telecom Company HEL, which was also evident from their sale purchase agreement, press releases, filings before the SEC, and their FIPB application, they claim to have achieved this by transferring a single share of a Cayman Island-based holding company and then entering into a series of framework agreements. This “device” of using the transfer of the Cayman Island company in the bid to avoid Capital Gains tax is precisely the tax avoidance devices that the Constitution bench in McDowell mandated, must be frustrated by the courts. The Court said: “It is up to the Court to take stock to determine the nature of the new and sophisticated legal devices to avoid tax and … to expose the devices for what they really are and to refuse to give judicial benediction.”

Moreover, in this case, as the Bombay High Court pointed out, the purpose of Vodafone to transfer the assets, shareholding and control of HEL from Hutch could not be achieved by just the transfer of the Cayman Island company. Therefore the set of framework agreements. In their words, “ The transaction between HTIL and VIH BV was structured so as to achieve the object of discontinuing the operations of HTIL in relation to the Indian mobile telecommunication operations by transferring the rights and entitlements of HTIL to VIH BV. HEL was at all times intended to be the target company and a transfer of the controlling interest in HEL was the purpose which was achieved by the transaction.”

Tax avoidance devices have been honed to a fine art by clever lawyers and consultants advising such corporations. Unfortunately, in the Vodafone and the Mauritius cases, the court has winked at them instead of frowning upon and frustrating them as mandated by the binding judgment in McDowell.

The case in a nutshell

I

Abhishek Gupta, Software Engineer, Kronos Incorporated, explained on Aug 4, 2013 :

Vodafone was embroiled in a $2.5 billion tax dispute over its purchase of Hutchison Essar Telecom services in April 2007. The transaction involved purchase of assets of an Indian Company, and therefore the transaction, or part thereof was liable to be taxed in India as per the allegations of tax department.

Vodafone Group entered India in 2007 through a subsidiary based in the Netherlands, which acquired Hutchison Telecommunications International Ltd’s (HTIL) stake in Hutchison Essar Ltd (HEL)—the joint venture that held and operated telecom licences in India. This agreement gave Vodafone control over 67% of HEL and extinguished Hong Kong-based Hutchison’s rights of control in India, a deal that cost the world’s largest telco $11.2 billion at the time.

The crux of the dispute had been whether or not the Indian Income Tax Department has jurisdiction over the transaction.

In January 2012, the Supreme Court passed the judgement in favour of Vodafone, saying that the Indian Income tax department had "no jurisdiction" to levy tax on overseas transaction between companies incorporated outside India.

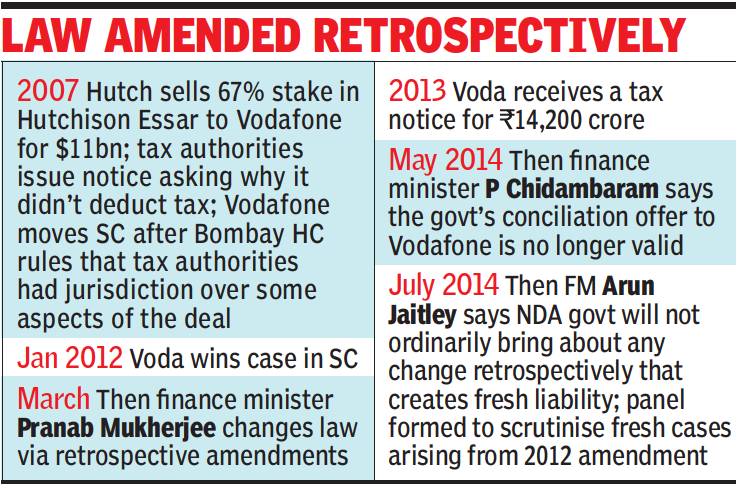

Government changed its Income Tax Act retrospectively and made sure that any company, in similar circumstances, is not able to avoid tax by operating out of tax-havens like Cayman Islands or Lichtenstein. In May 2012, Indian authorities confirmed that they were going to charge Vodafone about ₹ 20,000 crore (US $4.5 billion) in tax and fines.

Retrospective Taxation means [that] the old proceedings are being taxed as per the new rules.

II

Vodafone Plc is learning that when it comes to dogged persistence, its popular pug is not a patch on the Indian taxman. Last week, the government announced that it was giving up its ‘conciliation talks’ with the global giant and was going ahead with its earlier tax demand relating to the Hutch-Vodafone deal of 2007.

Hey, you’re saying, why is Vodafone again in the dock for avoiding tax? Didn’t the Supreme Court let it off the hook? Well, it’s a long story.

What is it?

Long long ago in 2007 Vodafone International Holdings BV decided to expand its footprint in the Indian mobile phone market by buying out Hutchison Essar.

But it decided to take the roundabout route; its subsidiary exchanged cash for shares with a similar holding company for Hutchison Essar, in far off Cayman Islands. Having sewn up the deal entirely offshore, where the Indian tax authorities had no say, Vodafone then proceeded to make Zoozoo advertisements .

The deal started a ‘wherever you go, we will follow’ saga of the IT department chasing the company. The Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that Vodafone’s actions were “within the four corners of law” .

It also advised Indian taxmen to “look at” the transaction instead of “looking through” it to attribute motives to the deal. What the Indian government saw however was over ₹20,000 crore in unpaid taxes, interest and penalty slipping out of its hands.

It decided to strike fear into the heart of companies by coming up with the General Anti-Avoidance Rule (GAAR). This rule basically said that the government could dig up past deals, all the way back to 1962. .

There was a huge hue and cry and GAAR was postponed to 2016. Still, the revenue officials persisted with their pet case as they felt they could net some good money in this and other high value acquisitions.

Why is it important?

Cases such as Vodafone have stirred up a global debate on the devious tax planning strategies and what governments can do to stymie them. After all, it is taxes that pad up the exchequer.

Standard methods employed by global companies are reducing the locally declared profits and shifting their profits to lower-tax locations. Governments around the world woke up to this trend , referred to as base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS).

Also, domestic firms who walk the straight and narrow path may be put at a disadvantage, as cross-border operators exploit the loopholes. There is also the moral hazard. If global biggies get away with paying no tax by employing clever accountants, wouldn’t domestic corporations be tempted to do the same?

Why should I care?

Knowing whether a company is paying its dues is important for investors because for one, it is proof that the reported profits do indeed exist.

Two, tax avoidance even within the confines of law can have big repercussions. It could knock out a company’s profits and reputation.

Finally, if you’re a law abiding citizen who pays all the dues and saves the receipts, you may be particular about checking if the company you are investing in is equally above board.

In your own dealings, if you come across grey areas in the tax rules, a penny saved in tax may lead to a pound in penalty to be paid later. Take a look at Vodafone, where demands for penalty and interest add up to two times the original tax bill.

Bottomline

Wherever you go, the taxman will follow. So when it comes to paying taxes, be faithful to the rules.

2014: India’s image plummets

Resolve the Vodafone tax dispute

(The author is Partner, Khaitan and Co.)

The Vodafone tax controversy is certainly one of the most high profile and most talked about tax disputes in India so far and has gained significant attention globally from investors, administrators as well as scholars. Let us put the dispute in context. In 2007, Vodafone acquired the stake of Hong Kong-based Hutchison Group in Hutchison Essar's telecom business in India.

It was an offshore deal where Vodafone Netherlands acquired ownership of a Cayman Island based entity called CGP Investments from a Hutch group entity also based in Cayman Island. So, while optically it was a pure offshore transaction between two non-resident entities (Vodafone and Hutchison) and they bought and sold shares of another non-resident entity (CGP), the Indian tax authorities took a position that by virtue of such an offshore deal, in effect and in substance, the parties have really sold stake in the Indian telecom business of Hutchison Essar. Therefore, they argued that profits realised from the indirect transfer of an Indian asset (telecom business in India) was taxable in the country and therefore, the buyer should have deducted applicable withholding tax while making payment of the purchase price of this business.

The Indian tax authorities are asserting their tax revenue claim. The apex court though did not uphold such a claim emphasising that the relevant law did not cover such an offshore transaction within its tax net in India and that certainty in tax laws is of paramount importance for foreign investors as well as for Indian residents.

The Supreme Court's interpretation of the provisions of the law in January 2012 (after about five years of the consummation of the transaction) in favour of Vodafone was followed by a retrospective amendment of the tax laws by the Indian government to overrule the apex court's verdict and lead to a revival of the tax demand against Vodafone. This has created significant uncertainty and has perhaps made the investor community wary of investing in India.

The story [till March 2014]

1. Offshore sale transaction between Hutchison Group, Hong Kong (Hutch) and Vodafone in the year 2007.

2. In the same year (2007), the tax authorities issued a show-cause notice to Vodafone, asking why it should not be treated as a defaulter for not deducting Indian withholding tax while making payments to Hutch. According to the tax authorities, this offshore transaction effectively resulted in transfer of an Indian asset and hence liable to capital gains tax in India.

3. The show-cause notice was challenged by Vodafone in a Writ Petition (WP) before the Bombay High Court (HC) which was dismissed in December 2008. The HC observed that prima facie Hutch had earned taxable capital gains in India as the income was earned from transfer of its business/ economic interest in the Indian company. The HC also took serious note of the fact that Vodafone did not produce some of the critical transaction documents which could have been instrumental in determining taxability of the transaction in India.

4. Thereafter, a Special Leave Petition (SLP) was filed by Vodafone before the SC. This SLP was dismissed and the SC directed the tax authorities to decide whether they had jurisdiction to proceed against Vodafone in the matter. However, the SC permitted Vodafone to challenge the decision of the tax authorities directly before the HC rather than first going through the normal channels of Commissioner (Appeals) and the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal.

5. In May 2010, the tax authorities passed an order taking the view that they had jurisdiction to proceed against Vodafone and accordingly treated the company as an 'assessee in default' for not withholding tax from payments made to Hutch even though it was an offshore deal between two non-resident parties.

6. Vodafone challenged this order of the tax authorities before the HC. The HC dismissed the case and ruled that the tax authorities indeed had jurisdiction to proceed against Vodafone as the income (capital gain) did accrue / arise in India by virtue of transfer of assets situated in India.

7. Aggrieved by the order of the HC, Vodafone approached the SC.

8. On 20 January 2012, the SC pronounced its ruling in favour of Vodafone holding that the transaction was not taxable in India and thus the company was not liable to withhold tax in India.

9. Soon thereafter, the Finance Act, 2012 amended Income Tax Act retrospectively to bring offshore indirect transfer of Indian assets (Vodafone like transactions) within the Indian tax net which triggered lot of criticism from the investor community globally.

10. Sensing the trouble and to allay fears of investors, the Prime Minister of India constituted an expert committee to review these retrospective amendments and to recommend changes to the government

11. The committee submitted its report in October 2012 to the government and since then there is no clarification or amendment as regards this provision

Since last year, the attempts to settle the tax dispute between Vodafone and the Indian government is another endless saga. According to recent media reports, the outcome of the settlement process seems to be uncertain.

The mechanics of the settlement process being adopted in Vodafone's case is shrouded in mystery. The settlement process began with Vodafone initiating a dispute resolution system under the Bilateral Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (BIPA) between India and the Netherlands and then wanting to resort to conciliation under the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNICATRAL) rules while the Indian government wanted to have it under Indian laws.

It is noteworthy that the ability to settle taxation matters under the Indian law is not free from doubt. Further, with Vodafone lately pressing for widening of the scope for conciliation to include its transfer pricing dispute as well, it is believed that the government is seeking to withdraw the conciliation talks which may now pave way for international arbitration proceedings. Under the BIPA, the dispute can be referred to an arbitral tribunal by either party to the dispute in accordance with UNICATRAL rules if the investor (Vodafone) so agrees. Thus, Vodafone may initiate the arbitration proceedings.

According to the BIPA, the decision of the arbitral tribunal shall be final and binding and the parties shall abide by and comply with the terms of the award. One needs to wait and watch how this turns out. It is also understood that the Indian government may take a position that taxation matters are outside the purview of BIPA.

From an equity and fairness perspective, Vodafone has a case to say that the position it took was based on its interpretation of the then existing law which even the apex court agreed to in its ruling delivered in January 2012. Importantly, where the tax authorities feel that it is demanding what is its rightful claim, the same is being demanded and enforced against the payer on account of its withholding tax non-compliance and not the payee to whom the income being taxed actually belongs. The expert committee constituted by the Prime Minister also recommended that the amendment which is not merely clarificatory in nature should be made prospectively and where it is made with retrospective effect, the payer should not be proceeded against and the provisions be applied to the payee to whom the income actually belongs.

The way things stand currently, it is not quite clear as to in which direction this dispute is likely to move. Given that clarity and certainty in fiscal laws including tax laws is of paramount importance, one would like to believe that post the upcoming elections, the next government is likely to give full attention to this long outstanding issue and seek to resolve it on a priority basis to maintain and promote India's image as an investor friendly country.

To this outstanding dispute, the latest addition is the Rs 3,700 crore tax demand on Vodafone on account of a transfer pricing dispute with the tax authorities. The authorities have taken a position that transfer pricing adjustments need to be made in the context of sale of call centre business. This new controversy is now before the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal for adjudication and ruling. It appears from latest media reports that the Indian government will look at conciliation route in respect of indirect transfer dispute (Hutch Essar deal) once the Tax Tribunal has given its ruling on the latest transfer pricing related dispute.

All in all, it seems imperative that the government will have to take this outstanding dispute head on and resolve it one way or other so as to send the clear message to international investors that India means business and that the government will do everything possible on its part to promote and encourage foreign investments in India.

2015: Bombay HC sets aside Rs. 3,700 crore tax

Bombay HC sets aside tax demand of Rs. 3,700 crore

In a major relief to British telecom major Vodafone in the transfer pricing case, the Bombay High Court on Thursday ruled in its favour, setting aside a >tax demand of Rs. 3,700 crore imposed on Vodafone India by the income tax authorities. This is likely to benefit multinational companies such as IBM, Royal Dutch Shell and Nokia that face similar tax demands.

The case dates back to financial year 2007-8 involving the sale of Vodafone India Services Private Ltd., the call centre business of Vodafone, to Hutchison, and the tax authorities demanded capital gain tax for this transaction. The Income Tax department had demanded that Rs.8,500 crore be added to the company’s taxable income.

Transfer pricing is referred to the setting of the price for goods and services sold between related legal entities within an enterprise. This is to ensure fair pricing of the asset transferred. For example, if a subsidiary company sells goods to a parent company, the cost of those goods is the transfer price.

The court decision came as Vodafone challenged the order of the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal >which held last year that it structured the deal with Hutchison Whampoa Properties, a company based in India, to circumvent transfer pricing norms, though it was an international transaction wherein there was no arm’s length dealing between the related entities.

Vodafone welcomes decision

Vodafone has repeatedly clashed with the authorities over taxes since it bought Hutchison’s mobile business in 2007.

Vodafone acquired the telecom business of Hutchison in India to enter the Indian market. And the British company is also fighting another case with the tax authorities relating to this transaction.

In this current >transfer pricing case, Vodafone argued in the High Court that the Income Tax Department had no jurisdiction in this case because the transaction was not an international one and did not attract any tax.

The dispute on transfer pricing surfaced after the Income Tax Department issued a draft transfer pricing order in December 2011 and added Rs. 8,500 crore to Vodafone’s taxable income for the sale of the call centre business. In 2013, the Income Tax Department issued a tax demand of Rs. 3,700 crore to Vodafone India.

However, the IT tribunal stayed the demand during the proceeding of the case and asked Vodafone to deposit Rs. 200 crore by February 15, 2014. It complied with the order.

However, Vodafone argued that the sale of the call centre business was between two domestic companies and the transfer pricing officer had no jurisdiction over the deal. On Thursday, Vodafone India did not issue any elaborate statement. It said: “Vodafone welcomes today’s decision by the Bombay High Court.”

The tax authorities are likely to challenge the decision in the Supreme Court.

In October [2014], Vodafone won a transfer pricing case having an additional demand of Rs.3,200 crore from the tax authorities in the Bombay High Court.

“The High Court has reversed the decision of the tax tribunal that the recasting of the framework agreement between taxpayer and Indian business partners was to be regarded as a transfer of call options by assesse to its Parent entity merely because the latter was a confirming party. The tribunal, in so holding had rejected taxpayers contention that Supreme Court in its own case had already settled the issue in its favor,” Arun Chhabra, Director, Grant Thornton Advisory said while commenting on the case.

2020: Vodafone wins Rs 20,000 cr arbitration

From: September 26, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

The Vodafone tax case: 2007-14

2021: Birla group’s entire ownership offered to government

August 5, 2021: The Times of India

From: August 5, 2021: The Times of India

From: August 5, 2021: The Times of India

From: August 5, 2021: The Times of India

From: August 5, 2021: The Times of India

From: August 5, 2021: The Times of India

Industrialist Kumar Mangalam Birla has offered to transfer his group’s entire ownership in Vodafone Idea (VI) to the government in exchange for a bailout package that would keep the cash-strapped telecom company from collapsing.

The offer

The billionaire businessman made the offer in a June 7 letter to cabinet secretary Rajiv Gauba while expressing his group’s inability to fund the company any further.

“It is with a sense of duty towards the 270 million Indians connected by Vodafone Idea, I am more than willing to hand over my stake in the company to any entity – public sector/government/domestic financial entity or any other that the government may consider worthy of keeping the company as a going concern," Birla said in the letter. Without the help, he said, the company’s operations would be driven to “an irretrievable point of collapse”.

The urgency

In September 2020, VI’s board had approved a plan to raise up to Rs 25,000 crore from investors. However, the company has not been able to raise the funds so far.

“To actively participate in this fundraising, the potential foreign investors (mostly non-Chinese and we are yet to approach any Chinese investors) want to see clear government intent to have a three-player telecom market (consistent with its public stance) through positive actions on long-standing requests such as clarity on adjusted gross revenue (AGR) liability; adequate moratorium on spectrum payment and most importantly, a floor pricing regime above the cost of service,” Birla said in his letter.

The debt and business

VI, a joint venture between Britain’s Vodafone Plc and India’s Aditya Birla Group, has a net debt of around Rs 1.8 lakh crore. Goldman Sachs estimates VI could be looking at a cash shortfall of Rs 23,400 crore until April 2022, as it needs to pay near about that amount in debt, spectrum usage and licencing fee by then. The company recently reported a net loss of Rs 6,985.1 crore for the quarter ending March 31. Vodafone Plc has said it will not put any additional investment in the India business.

Despite bleeding heavily, the company has been unable to significantly raise tariffs due to the stiff competition. Since the entry of Reliance Jio in 2016, mobile tariffs in the country have plummeted.

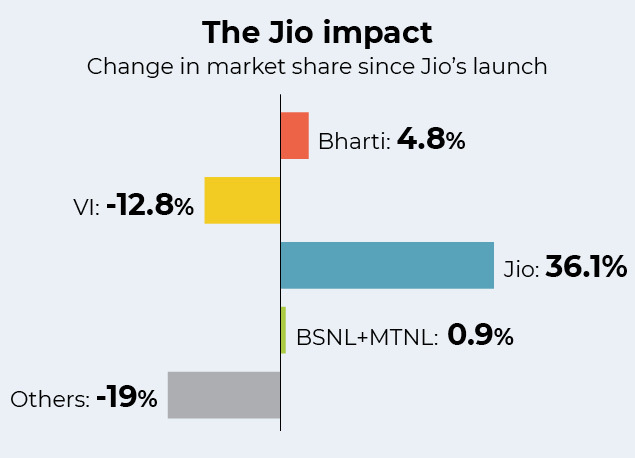

In a bid to gain customers, Jio, backed by its cash-rich parent, has offered rock-bottom data tariffs and free voice to customers. Since Jio's launch, VI's market share has shrunk by about 13%. Jio, as a new entrant, also doesn't have the burden of past spectrum payments to the government.

While both VI and Airtel recently hiked their entry-level prepaid mobile tariffs, the pressure from Jio is unlikely to lead to much on that front. Analysts say VI especially needs immediate tariff hikes to improve its cash generation as it faces over Rs 22,000 crore in dues from December 2021 to April 2022.

But why the government?

First, the collapse of VI would result in a duopoly of two players Jio and Airtel (not counting BSNL), which in the long-term could harm customers. Then, the bulk of the company’s debt burden is in government dues. Out of VI’s net debt of Rs 1.8 lakh crore, government dues in the form of deferred spectrum payment (Rs 96,270 crore) and AGR dues (Rs 50,399 crore) add up to around Rs 1.47 lakh crore or over 80% of its debt. The company also had a debt of Rs 23,080 crore from banks and financial institutions.

This is why it came to this. The dues had been building up over the years, but a Supreme Court judgment in 2019 dealt a big blow to telecom firms. For 14 years telecom companies were locked in a legal battle with the Centre over the definition of ‘adjusted gross revenue’ on which the spectrum charges and licence fees they pay to the government depend.

The operators said that AGR should comprise revenue earned only from telecom services, while the government said that AGR should include all revenue, including those from non-core operations. A telecom company also earns a sizable revenue from things like renting or selling fixed assets, selling scrap, from corporate deposits, real estate transactions, by selling handsets or by way of dividend or interest on its investments. If all this is included as revenue for calculating AGR, their outgo increases substantially.

That’s what happened after the SC ruled in favour of the government. With the apex court rejecting a plea by telecom firms, including VI, seeking reassessment of how the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) calculates the due they owe, the door is all but closed for any negotiations. While DoT pegged VI’s AGR dues at Rs 58,254 crore, the company had self-assessed it at Rs 21,533 crore. So far it has paid Rs 7,854 crore of its AGR dues.

Does VI becoming BSNL help?

In a recent research note, Deutsche Bank AG's telecom analysts noted that India was “the most painful market to operate a telecom in” and “a long history of extracting as much as possible from the sector has left a legacy of repeated business failures – including the largest bankruptcy in Indian corporate history, Reliance Communications. That is likely to be trumped by VI”. “We think the only viable solution for India to keep VI is for the government to convert its debt into equity, preferably while merging it with BSNL, and then providing it a clear commercial mandate based on profitability targets and incentives,” the analysts said.

Will it happen?

However, taking over a private company is easier said than done. First, for the government, it means foregoing potential revenue in AGR and spectrum dues.

Second, the government’s track record of running two public sector telecom companies – BSNL and MTNL – has been close to a disaster. Will it want to burn its fingers again by taking over a private company?

Third, fixing a floor price for tariffs, which Birla has demanded, falls in the domain of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (Trai), which may run into trouble with the Competition Commission of India if it moves to fix tariffs.

Fourth, fixing a floor price, which is higher than the current tariffs will be a politically unpopular decision, especially during the pandemic. “Also consider that floor prices can be put in place, but add-on promotions can always occur to circumvent regulation, such as handset subsidies or content deals,’ says the Deutsche Bank report.

The only viable option for the government, if it wants to keep VI afloat, would then be to reduce its licence fee and offer more time to telecom companies to pay their deferred spectrum instalments. But will that be enough to save VI?

The need for competition

The competition in the telecom markets has been instrumental in bringing down data and voice tariffs as well as expanding its reach within the country. However, competition in the market has been reducing, especially after the entry of Jio. Only three incumbents – Airtel, VI and state-owned BSNL – remain in the market but with VI and BSNL struggling financially, the competition could decline further. This could lead to higher tariffs later, experts say.

How they came and went

- Airtel and Sterling Group merger in 2005

- Spice and Telekom merger in 2006

- Vodafone acquires Hutchison Essar stake in 2007

- Acquisition of Spice Communication by Idea Cellular in 2008

- Reliance Industry and Infotel merger in 2010

- Licence of Loop Mobile expired in September 2014

- Reliance Jio-Infocom Ltd entered market in September 2016

- Sistema merged with Reliance Comm in Sept-Dec 2017

- Telenor merged with Bharti Airtel in June 2018

- Vodafone merged with Idea in September 2018