Valaiyan

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Valaiyan

The Valaiyans are described, in the Manual of Madura district (1868), as “a low and debased class. Their name is supposed to be derived from valai, a net, and to have been given to them from their being constantly employed in netting game in the jungles. Many of them still live by the net; some catch fish; some smelt iron. Many are engaged in cultivation, as bearers of burdens, and in ordinary cooly work. The tradition that a Valaiya woman was the mother of the Vallambans seems to show that the Valaiyans must be one of the most ancient castes in the country.” In the Tanjore Manual they are described as “inhabitants of the country inland who live by snaring birds, and fishing in fresh waters. They engage also in agricultural labour and cooly work, such as carrying loads, husking paddy (rice), and cutting and selling fire-wood. They are a poor and degraded class.” The Valaiyans are expert at making cunningly devised traps for catching rats and jungle fowl. They have “a comical fairy-tale of the origin of the war, which still goes on between them and the rat tribe. It relates how the chiefs of the rats met in conclave, and devised the various means for arranging and harassing the enemy, which they still practice with such effect.” The Valaiyans say that they were once the friends of Siva, but were degraded for the sin of eating rats and frogs.

In the Census Report, 1901, the Valaiyans are described as “a shikāri (hunting) caste in Madura and Tanjore. In the latter the names Ambalakāran, Sērvaikāran, Vēdan, Siviyān, and Kuruvikkāran are indiscriminately applied to the caste.” There is some connection between Ambalakārans, Muttiriyans, Mutrāchas, Urālis, Vēdans, Valaiyans, and Vēttuvans, but in what it exactly consists remains to be ascertained. It seems likely that all of them are descended from one common parent stock. Ambalakārans claim to be descended from Kannappa Nāyanar, one of the sixty-three Saivite saints, who was a Vēdan or hunter by caste. In Tanjore the Valaiyans declare themselves to have a similar origin, and in that district Ambalakāran and Muttiriyan seem to be synonymous with Valaiyan. Moreover, the statistics of the distribution of the Valaiyans show that they are numerous in the districts where Ambalakārans are few, and vice versâ, which looks as though certain sections had taken to calling themselves Ambalakārans. The upper sections of the Ambalakārans style themselves Pillai, which is a title properly belonging to Vellālas, but the others are usually called Mūppan in Tanjore, and Ambalakāran, Muttiriyan, and Sērvaikāran in Trichinopoly. The usual title of the Valaiyans, so far as I can gather, is Mūppan, but some style themselves Sērvai and Ambalakāran.” The Madura Valaiyans are said to be “less brāhmanised than those in Tanjore, the latter employing Brāhmans as priests, forbidding the marriage of widows, occasionally burning their dead, and being particular what they eat. But they still cling to the worship of all the usual village gods and goddesses.” In some places, it is said, the Valaiyans will eat almost anything, including rats, cats, frogs and squirrels.

Like the Pallans and Paraiyans, the Valaiyans, in some places, live in streets of their own, or in settlements outside the villages. At times of census, they have returned a large number of sub-divisions, of which the following may be cited as examples:—

• Monathinni. Those who eat the vermin of the soil.

• Pāsikatti (pāsi, glass bead).

• Saragu, withered leaves.

• Vanniyan. Synonym of the Palli caste.

• Vellāmputtu, white-ant hill.

In some places the Saruku or Saragu Valaiyans have exogamous kīlais or septs, which, as among the Maravans and Kallans, run in the female line. Brothers and sisters belong to the same kīlai as that of their mother and maternal uncle, and not of their father.

It is stated, in the Gazetteer of the Madura district, that “the Valaiyans are grouped into four endogamous sub-divisions, namely, Vahni, Valattu, Karadi, and Kangu. The last of these is again divided into Pāsikatti, those who use a bead necklet instead of a tāli (as a marriage badge), and Kāraikatti, those whose women wear horsehair necklaces like the Kallans. The caste title is Mūppan. Caste matters are settled by a headman called the Kambliyan (blanket man), who lives at Aruppukōttai, and comes round in state to any village which requires his services, seated on a horse, and accompanied by servants who hold an umbrella over his head and fan him. He holds his court seated on a blanket. The fines imposed go in equal shares to the aramanai (literally palace, i.e., to the headman himself), and to the oramanai, that is, the caste people.

It is noted by Mr. F. R. Hemingway that “the Valaiyans of the Trichinopoly district say that they have eight endogamous sub-divisions, namely, Sarahu (or Saragu), Ettarai Kōppu, Tānambanādu or Valuvādi, Nadunāttu or Asal, Kurumba, Vanniya, Ambunādu, and Punal. Some of these are similar to those of the Kallans and Ambalakārans.” In the Gazetteer of the Tanjore district, it is recorded that the Valaiyans are said to possess “endogamous sub-divisions called Vēdan, Sulundukkāran and Ambalakkāran. The members of the first are said to be hunters, those of the second torch-bearers, and those of the last cultivators. They are a low caste, are refused admittance into the temples, and pollute a Vellālan by touch. Their occupations are chiefly cultivation of a low order, cooly work, and hunting. They are also said to be addicted to crime, being employed by Kallans as their tools.”

Adult marriage is the rule, and the consent of the maternal uncle is necessary. Remarriage of widows is freely permitted. At the marriage ceremony, the bridegroom’s sister takes up the tāli (marriage badge), and, after showing it to those assembled, ties it tightly round the neck of the bride. To tie it loosely so that the tāli string touches the collar-bone would be considered a breach of custom, and the woman who tied it would be fined. The tāli-tying ceremony always takes place at night, and the bridegroom’s sister performs it, as, if it was tied by the bridegroom, it could not be removed on his death, and replaced if his widow wished to marry again. Marriages generally take place from January to May, and consummation should not be effected till the end of the month Ādi, lest the first child should be born in the month of Chithre, which would be very inauspicious. There are two Tamil proverbs to the effect that “the girl should remain in her mother’s house during Ādi,” and “if a child is born in Chithre, it is ruinous to the house of the mother-in-law.”

In the Gazetteer of the Madura district, it is stated that “at weddings, the bridegroom’s sister ties the tāli, and then hurries the bride off to her brother’s house, where he is waiting. When a girl attains maturity, she is made to live for a fortnight in a temporary hut, which she afterwards burns down. While she is there, the little girls of the caste meet outside it, and sing a song illustrative of the charms of womanhood, and its power of alleviating the unhappy lot of the bachelor. Two of the verses say:—

What of the hair of a man?

It is twisted, and matted, and a burden.

What of the tresses of a woman?

They are as flowers in a garland, and a glory.

What of the life of a man?

It is that of the dog at the palace gate.

What of the days of a woman?

They are like the gently waving leaves in a festoon.

“Divorce is readily permitted on the usual payments, and divorcées and widows may remarry. A married woman who goes astray is brought before the Kambliyan, who delivers a homily, and then orders the man’s waist-string to be tied round her neck. This legitimatises any children they may have.” The Valaiyans of Pattukkōttai in the Tanjore district say that intimacy between a man and woman before marriage is tolerated, and that the children of such a union are regarded as members of the caste, and permitted to intermarry with others, provided the parents pay a nominal penalty imposed by the caste council.

In connection with the Valaiyans of the Trichinopoly district, Mr. Hemingway writes that “they recognise three forms of marriage, the most usual of which consists in the bridegroom’s party going to the girl’s house with three marakkāls of rice and a cock on an auspicious day, and in both parties having a feast there. Sometimes the young man’s sister goes to the girl’s house, ties a tāli round her neck, and takes her away. The ordinary form of marriage, called big marriage, is sometimes used with variations, but the Valaiyans do not like it, and say that the two other forms result in more prolific unions. They tolerate unchastity before marriage, and allow parties to marry even after several children have been born, the marriage legitimatising them. They permit remarriage of widows and divorced women. Women convicted of immorality are garlanded with erukku (Calotropis gigantea) flowers, and made to carry a basket of mud round the village. Men who too frequently offend in this respect are made to sit with their toes tied to the neck by a creeper. When a woman is divorced, her male children go to the husband, and she is allowed to keep the girls.”

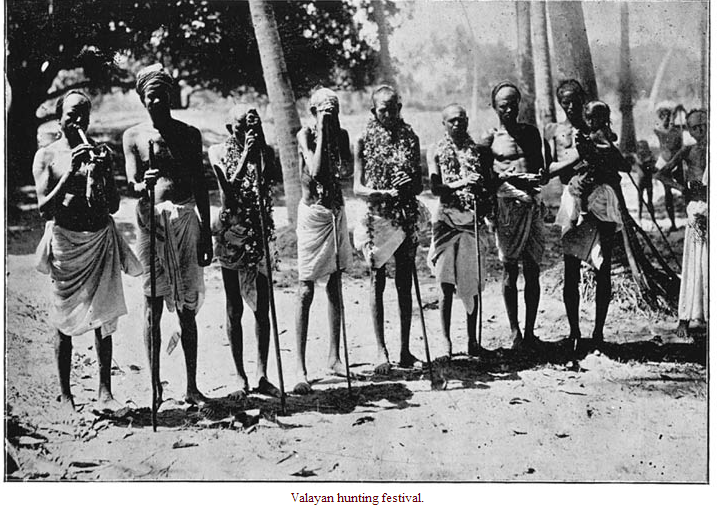

The tribal gods of the Valaiyans are Singa Pidāri (Aiyanar) and Padinettāmpadi Karuppan. Once a year, on the day after the new-moon in the month Māsi (February to March), the Valaiyans assemble to worship the deity. Early in the morning they proceed to the Aiyanar temple, and, after doing homage to the god, go off to the forest to hunt hares and other small game. On their return they are met by the Valaiyan matrons carrying coloured water or rice (ālām), garlands of flowers, betel leaves and areca nuts. The ālām is waved over the men, some of whom become inspired and are garlanded. While they are under inspiration, the mothers appeal to them to name their babies. The products of the chase are taken to the house of the headman and distributed. At a festival, at which Mr. K. Rangachari was present, at about ten o’clock in the morning all the Valaiya men, women, and children, dressed up in holiday attire, swarmed out of their huts, and proceeded to a neighbouring grove. The men and boys each carried a throwing stick, or a digging stick tipped with iron. On arrival at the grove, they stood in a row, facing east, and, throwing down their sticks, saluted them, and prostrated themselves before them. Then all took up their sticks, and some played on reed pipes. Some of the women brought garlands of flowers, and placed them round the necks of four men, who for a time stood holding in their hands their sticks, of which the ends were stuck in the ground.

After a time they began to shiver, move quickly about, and kick those around them. Under the influence of their inspiration, they exhibited remarkable physical strength, and five or six men could not hold them. Calling various people by name, they expressed a hope that they would respect the gods, worship them, and offer to them pongal (boiled rice) and animal sacrifices. The women brought their babies to them to be named. In some places, the naming of infants is performed at the Aiyanar temple by any one who is under the influence of inspiration. Failing such a one, several flowers, each with a name attached to it, are thrown in front of the idol. A boy, or the pūjāri (priest) picks up one of the flowers, and the infant receives the name which is connected with it. The Valaiyans are devoted to devil worship, and, at Orattanādu in the Tanjore district, every Valaiyan backyard is said to contain an odiyan (Odina Wodier) tree, in which the devil is supposed to live. It is noted by Mr. W. Francis that “certain of the Valaiyans who live at Ammayanāyakkanūr are the hereditary pūjāris to the gods of the Sirumalai hills. Some of these deities are uncommon, and one of them, Pāppārayan, is said to be the spirit of a Brāhman astrologer whose monsoon forecast was falsified by events, and who, filled with a shame rare in unsuccessful weather prophets, threw himself off a high point on the range.”

According to Mr. Hemingway, the Valaiyans have a special caste god, named Muttāl Rāvuttan, who is the spirit of a dead Muhammadan, about whom nothing seems to be known.

The dead are as a rule buried with rites similar to those of the Kallans and Agamudaiyans. The final death ceremonies (karmāndhiram) are performed on the sixteenth day. On the night of the previous day, a vessel filled with water is placed on the spot where the deceased breathed his last, and two cocoanuts, with the pores (’eyes’) open, are deposited near it. On the following morning, all proceed to a grove or tank (pond). The eldest son, or other celebrant, after shaving and bathing, marks out a square space on the ground, and, placing a few dry twigs of Ficus religiosa and Ficus bengalensis therein, sets fire to them. Presents of rice and other food-stuffs are given to beggars and others. The ceremony closes with the son and sapindas, who have to observe pollution, placing new cloths on their heads. Mr. Francis records that, at the funeral ceremonies, “the relations go three times round a basket of grain placed under a pandal (booth), beating their breasts and singing:—

For us the kanji (rice gruel): kailāsam (the abode of Siva) for thee;

Rice for us; for thee Svargalōkam,

and then wind turbans round the head of the deceased’s heir, in recognition of his new position as chief of the family. When a woman loses her husband, she goes three times round the village mandai (common), with a pot of water on her shoulder. After each of the first two journeys, the barber makes a hole in the pot, and at the end of the third he hurls down the vessel, and cries out an adjuration to the departed spirit to leave the widow and children in peace.” It is noted, in the Gazetteer of the Tanjore district, that “one of the funeral ceremonies is peculiar, though it is paralleled by practices among the Paraiyans and Karaiyāns. When the heir departs to the burning-ground on the second day, a mortar is placed near the outer door of his house, and a lamp is lit inside. On his return, he has to upset the mortar, and worship the light.”

Vālan.—For the following note on the Vālan and Katal Arayan fishing castes of the Cochin State, I am indebted to Mr. L. K. Anantha Krishna Aiyar.

The name Vālan is derived from vala, meaning fish in a tank. Some consider the word to be another form of Valayan, which signifies a person who throws a net for fishing. According to the tradition and current belief of these people, they were brought to Kērala by Parasurāma for plying boats and conveying passengers across the rivers and backwaters on the west coast. Another tradition is that the Vālans were Arayans, and they became a separate caste only after one of the Perumāls had selected some of their families for boat service, and conferred on them special privileges. They even now pride themselves that their caste is one of remote antiquity, and that Vedavyasa, the author of the Purānas, and Guha, who rendered the boat service to the divine Rāma, Sita, and Lakshmana, across the Ganges in the course of their exile to the forest, were among the caste-men.

There are no sub-divisions in the caste, but the members thereof are said to belong to four exogamous illams (houses of Nambūtiris), namely, Alayakad, Ennalu, Vaisyagiriam, and Vazhapally, which correspond to the gōtras of the Brāhmans, or to four clans, the members of each of which are perhaps descended from a common ancestor. According to a tradition current among them, they were once attached to the four Nambūtiri illams above mentioned for service of some kind, and were even the descendants of the members of the illams, but were doomed to the present state of degradation on account of some misconduct. Evidently, the story is looked up to to elevate themselves in social status. I am inclined to believe that they must have been the Atiyars slaves) of the four aforesaid Brāhman families, owing a kind of allegiance (nambikooru) like the Kanakkans to the Chittur Manakkal Nambūtripād in Perumanam of the Trichur tāluk. Even now, these Brāhman families are held in great respect by the Vālans, who, when afflicted with family calamities, visit the respective illams with presents of a few packets of betel leaves and a few annas, to receive the blessings of their Brāhman masters, which, according to their belief, may tend to avert them.

The low sandy tract of land on each side of the backwater is the abode of these fishermen. In some places, more especially south of Cranganore, their houses are dotted along the banks of the backwater, often nearly hidden by cocoanut trees, while at intervals the white picturesque fronts of numerous Roman Catholic and Romo-Syrian churches are perceived. These houses are in fact mere flimsy huts, a few of which, occupied by the members of several families, may be seen huddled together in the same compound abounding in a growth of cocoanut trees, with hardly enough space to dry their fish and nets. In the majority of cases, the compounds belong to jenmis (landlords), who lease them out either rent-free or on nominal rent, and who often are so kind as to allow them some cocoanuts for their consumption, and leaves sufficient to thatch their houses. About ten per cent. of their houses are built of wood and stones, while a large majority of them are made of mud or bamboo framework, and hardly spacious enough to accommodate the members of the family during the summer months. Cooking is done outside the house, and very few take rest inside after hard work, for their compounds are shady and breezy, and they may be seen basking in the sun after midnight toil, or drying the nets or fish. Their utensils are few, consisting of earthen vessels and enamel dishes, and their furniture of a few wooden planks and coarse mats to serve as beds.

The girls of the Vālans are married both before and after puberty, but the tāli-kettu kalyānam (tāli-tying marriage) is indispensable before they come of age, as otherwise they and their parents are put out of caste. Both for the tāli-tying ceremony and for the real marriage, the bride and bridegroom must be of different illams or gōtras. In regard to the former, as soon as an auspicious day is fixed, the girl’s party visit the Aravan with a present of six annas and eight pies, and a few packets of betel leaves, when he gives his permission, and issues an order to the Ponamban, his subordinate of the kadavu (village), to see that the ceremony is properly conducted. The Ponamban, the bridegroom and his party, go to the house of the bride. At the appointed hour, the Ponambans and the castemen of the two kadavus assemble after depositing six annas and eight pies in recognition of the presence of the Aravan, and the tāli is handed over by the priest to the bridegroom, who ties it round the neck of the bride amidst the joyous shouts of the multitude assembled. The ceremony always takes place at night, and the festivities generally last for two days. It must be understood that the tāli tier is not necessarily the husband of the girl, but is merely the pseudo-bridegroom or pseudo-husband, who is sent away with two pieces of cloth and a few annas at the termination of the ceremony. Should he, however, wish to have the girl as his wife, he should, at his own expense, provide her with a tāli, a wedding dress, and a few rupees as the price of the bride. Generally it is the maternal uncle of the girl who provides her with the first two at the time of the ceremony.

The actual marriage is more ceremonial in its nature. The maternal uncle, or the father of a young Vālan who wishes to marry, first visits the girl, and, if he approves of the match for his nephew or son, the astrologer is consulted so as to ensure that the horoscopes agree. If astrology does not stand in the way, they forthwith proceed to the girl’s house, where they are well entertained. The bride’s parents and relatives return the visit at the bridegroom’s house, where they are likewise treated to a feast. The two parties then decide on a day for the formal declaration of the proposed union. On that day, a Vālan from the bridegroom’s village, seven to nine elders, and the Ponamban under whom the bride is, meet, and, in the presence of those assembled, a Vālan from each party deposits on a plank four annas and a few betel leaves in token of enangu māttam or exchange of co-castemen from each party for the due fulfilment of the contract thus publicly entered into. Then they fix the date of the marriage, and retire from the bride’s house. On the appointed day, the bridegroom’s party proceed to the bride’s house with two pieces of cloth, a rupee or a rupee and a half, rice, packets of betel leaves, etc. The bride is already dressed and adorned in her best, and one piece of cloth, rice and money, are paid to her mother as the price of the bride. After a feast, the bridal party go to the bridegroom’s house, which is entered at an auspicious hour. They are received at the gate with a lamp and a vessel of water, a small quantity of which is sprinkled on the married couple. They are welcomed by the seniors of the house and seated together, when sweets are given, and the bride is formally declared to be a member of the bridegroom’s family. The ceremony closes with a feast, the expenses in connection with which are the same on both sides.

A man may marry more than one wife, but no woman may enter into conjugal relations with more than one man. A widow may, with the consent of her parents, enter into wedlock with any member of her caste except her brothers-in-law, in which case her children by her first husband will be looked after by the members of his family. Divorce is effected by either party making an application to the Aravan, who has to be presented with from twelve annas to six rupees and a half according to the means of the applicant. The Aravan, in token of dissolution, issues a letter to the members of the particular village to which the applicant belongs, and, on the declaration of the same, he or she has to pay to his or her village castemen four annas.

When a Vālan girl comes of age, she is lodged in a room of the house, and is under pollution for four days. She is bathed on the fourth day, and the castemen and women of the neighbourhood, with the relatives and friends, are treated to a sumptuous dinner. There is a curious custom called theralikka, i.e., causing the girl to attain maturity, which consists in placing her in seclusion in a separate room, and proclaiming that she has come of age. Under such circumstances, the caste-women of the neighbourhood, with the washerwoman, assemble at the house of the girl, when the latter pours a small quantity of gingelly (Sesamum) oil on her head, and rubs her body with turmeric powder, after which she is proclaimed as having attained puberty. She is bathed, and lodged in a separate room as before, and the four days’ pollution is observed. This custom, which exists also among other castes, is now being abandoned by a large majority of the community.

In respect of inheritance, the Vālans follow a system, which partakes of the character of succession from father to son, and from maternal uncle to nephew. The self-acquired property is generally divided equally between brothers and sons, while the ancestral property, if any, goes to the brothers. The great majority of the Vālans are mere day-labourers, and the property usually consists of a few tools, implements, or other equipments of their calling.

The Vālans, like other castes, have their tribal organisation, and their headman (Aravan or Aravar) is appointed by thītturam or writ issued by His Highness the Rāja. The Aravan appoints other social heads, called Ponamban, one, two, or three of whom are stationed at each dēsam (village) or kadavu. Before the development of the Government authority and the establishment of administrative departments, the Aravans wielded great influence and authority, as they still do to a limited extent, not only in matters social, but also in civil and criminal disputes between members of the community. For all social functions, matrimonial, funeral, etc., their permission has to be obtained and paid for. The members of the community have to visit their headman, with presents of betel leaves, money, and sometimes rice and paddy (unhusked rice). The headman generally directs the proper conduct of all ceremonies by writs issued to the Ponambans under him. The Ponambans also are entitled to small perquisites on ceremonial occasions. The appointment of Aravan, though not virtually hereditary, passes at his death to the next qualified senior member of his family, who may be his brother, son, or nephew, but this rule has been violated by the appointment of a person from a different family. The Aravan has the honour of receiving from His Highness the Rāja a present of two cloths at the Ōnam festival, six annas and eight pies on the Athachamayam day, and a similar sum for the Vishu. At his death, the ruler of the State sends a piece of silk cloth, a piece of sandal-wood, and about ten rupees, for defraying the expenses of the funeral ceremonies. The Vālans profess Hinduism, and Siva, Vishnu, and the heroes of the Hindu Purānas are all worshipped. Like other castes, they entertain special reverence for Bhagavathi, who is propitiated with offerings of rice-flour, toddy, green cocoanuts, plantain fruits, and fowls, on Tuesdays and Fridays.

A grand festival, called Kumbhom Bharani (cock festival), is held in the middle of March, when Nāyars and low caste men offer up cocks to Bhagavathi, beseeching immunity from diseases during the ensuing year. In fact, people from all parts of Malabar, Cochin, and Travancore, attend the festival, and the whole country near the line of march rings with shouts of “Nada, nada” (walk or march) of the pilgrims to Cranganore, the holy residence of the goddess. In their passage up to the shrine, the cry of “Nada, nada” is varied by unmeasured abuse of the goddess. The abusive language, it is believed, is acceptable to her, and, on arrival at the shrine, they desecrate it in every conceivable manner, in the belief that this too is acceptable. They throw stones and filth, howling volleys of abuse at the shrine. The chief of the Arayan caste, Koolimuttah Arayan, has the privilege of being the first to be present on the occasion. The image in the temple is said to have been recently introduced. There is a door in the temple which is apparently of stone, fixed in a half-opened position.

A tradition, believed by Hindus and Christians, is attached to this, which asserts that St. Thomas and Bhagavathi held a discussion at Palliport about the respective merits of the Christian and Hindu religions. The argument became heated, and Bhagavathi, considering it best to cease further discussion, decamped, and, jumping across the Cranganore river, made straight for the temple. St. Thomas, not to be outdone, rapidly gave chase, and, just as the deity got inside the door, the saint reached its outside, and, setting his foot between it and the door-post, prevented its closure. There they both stood until the door turned to stone, one not allowing its being opened, and the other its being shut. Another important festival, which is held at Cranganore, is the Makara Vilakku, which falls on the first of Makaram (about the 15th January), during the night of which there is a good deal of illumination both in and round the temple. A procession of ten or twelve elephants, all fully decorated, goes round it several times, accompanied by drums and instrumental music. Chourimala Iyappan or Sāstha, a sylvan deity, whose abode is Chourimala in Travancore, is a favourite deity of the Vālans. In addition, they worship the demi-gods or demons Kallachan Muri and Kochu Mallan, who are ever disposed to do them harm, and who are therefore propitiated with offerings of fowls. They have a patron, who is also worshipped at Cranganore. The spirits of their ancestors are also held in great veneration by these people, and are propitiated with offerings on the new moon and Sankranthi days of Karkadakam, Thulam, and Makaram. The most important festivals observed by the Vālans in common with other castes are Mandalam Vilakku, Sivarāthri, Vishu, Ōnam, and Desara.

Mandalam Vilakku takes place during the last seven days of Mandalam (November to December). During this festival the Vālans enjoy themselves with music and drum-beating during the day. At night, some of them, developing hysterical fits, profess to be oracles, with demons such as Gandharva, Yakshi, or Bhagavathi, dwelling in their bodies in their incorporeal forms. Consultations are held as to future events, and their advice is thankfully received and acted upon. Sacrifices of sheep, fowls, green cocoanuts, and plantain fruits are offered to the demons believed to be residing within, and are afterwards liberally distributed among the castemen and others present. The Sivarāthri festival comes on the last day of Magha. The whole day and night are devoted to the worship of Siva, and the Vālans, like other castes, go to Alvai, bathe in the river, and keep awake during the night, reading the Siva Purāna and reciting his names. Early on the following morning, they bathe, and make offerings of rice balls to the spirits of the ancestors before returning home.

The Vālans have no temples of their own , but, on all important occasions, worship the deities of the temples of the higher castes, standing at a long distance from the outer walls of the sacred edifice. On important religious occasions, Embrans are invited to perform the Kalasam ceremony, for which they are liberally rewarded. A kalasam is a pot, which is filled with water. Mango leaves and dharba grass are placed in it. Vēdic hymns are repeated, with one end of the grass in the water, and the other in the hand. Water thus sanctified is used for bathing the image. From a comparison of the religion of the Vālans with that of allied castes, it may be safely said that they were animists, but have rapidly imbibed the higher forms of worship. They are becoming more and more literate, and this helps the study of the religious works. There are some among them, who compose Vanchipāttu (songs sung while rowing) with plots from their Purānic studies.

The Vālans either burn or bury their dead. The chief mourner is either the son or nephew of the dead person, and he performs the death ceremonies as directed by the priest (Chithayan), who attends wearing a new cloth, turban, and the sacred thread. The ceremonies commence on the second, fifth, or seventh day, when the chief mourner, bathing early in the morning, offers pinda bali (offerings of rice balls) to the spirit of the deceased. This is continued till the thirteenth day, when the nearest relatives get shaved. On the fifteenth day, the castemen of the locality, the friends and relatives, are treated to a grand dinner, and, on the sixteenth day, another offering (mana pindam) is made to the spirit of the departed, and thrown into the backwater close by. Every day during the ceremonies, a vessel full of rice is given to the priest, who also receives ten rupees for his services.

If the death ceremonies are not properly performed, the ghost of the deceased is believed to haunt the house. An astrologer is then consulted, and his advice is invariably followed. What is called Samhara Hōmam (sacred fire) is kept up, and an image of the dead man in silver or gold is purified by the recitation of holy mantrams. Another purificatory ceremony is performed, after which the image is handed over to a priest at the temple, with a rupee or two. This done, the death ceremonies are performed. The ears of Vālan girls are, as among some other castes, pierced when they are a year old, or even less, and a small quill, a piece of cotton thread, or a bit of ]wood, is inserted into the hole. The wound is gradually healed by the application of cocoanut oil. A piece of lead is then inserted in the hole, which is gradually enlarged by means of a piece of plantain, cocoanut, or palmyra leaf rolled up.

The Vālans are expert rowers, and possess the special privilege of rowing from Thripunathura the boat of His Highness the Rāja for his installation at the Cochin palace, when the Aravan, with sword in hand, has to stand in front of him in the boat. Further, on the occasion of any journey of the Rāja along the backwaters on occasions of State functions, such as a visit of the Governor of Madras, or other dignitary, the headman leads the way as an escort in a snake-boat rowed with paddles, and has to supply the requisite number of men for rowing the boats of the high official and his retinue. The Katal Arayans, or sea Arayans, who are also called Katakkoti, are lower in status than the Vālans, and, like them, live along the coast. They were of great service to the Portuguese and the Dutch in their palmy days, acting as boatmen in transhipping their commodities and supplying them with fish.

The Katal Arayans were, in former times, owing to their social degradation, precluded from travelling along the public roads. This disability was, during the days of the Portuguese supremacy, taken advantage of by the Roman Catholic missionaries, who turned their attention to the conversion of these poor fishermen, a large number of whom were thus elevated in the social scale. The Katal Arayans are sea fishermen. On the death of a prince of Malabar, all fishing is temporarily prohibited, and only renewed after three days, when the spirit of the departed is supposed to have had time enough to choose its abode without molestation. Among their own community, the Katal Arayans distinguish themselves by four distinct appellations, viz., Sankhan, Bharatan, Amukkuvan, and Mukkuvan. Of these, Amukkuvans do priestly functions. The castemen belong to four septs or illams, namely, Kattotillam, Karotillam, Chempotillam, and Ponnotillam.

Katal Arayan girls are married both before and after puberty. The tāli-tying ceremony, which is compulsory in the case of Vālan girls before they come of age, is put off, and takes place along with the real marriage. The preliminary negotiations and settlements thereof are substantially the same as those prevailing among the Vālans. The auspicious hour for marriage is between three and eight in the morning, and, on the previous evening, the bridegroom and his party arrive at the house of the bride, where they are welcomed and treated to a grand feast, after which the guests, along with the bride and bridegroom seated somewhat apart, in a pandal tastefully decorated and brightly illuminated, are entertained with songs of the Vēlan (washerman) and his wife alluding to the marriage of Sīta or Parvathi, in the belief that they will bring about a happy conjugal union. These are continued till sunrise, when the priest hands over the marriage badge to the bridegroom, who ties it round the neck of the bride. The songs are again continued for an hour or two, after which poli begins. The guests who have assembled contribute a rupee, eight annas, or four annas, according to their means, which go towards the remuneration of the priest, songsters, and drummers. The guests are again sumptuously entertained at twelve o’clock, after which the bridegroom and his party return with the bride to his house. At the time of departure, or nearly an hour before it, the bridegroom ties a few rupees or a sovereign to a corner of the bride’s body-cloth, probably to induce her to accompany him. Just then, the bride-price, which is 101 puthans, or Rs. 5–12–4, is paid to her parents. The bridal party is entertained at the bridegroom’s house, where, at an auspicious hour, the newly married couple are seated together, and served with a few pieces of plantain fruits and some milk, when the bride is formally declared to be a member of her husband’s family. If a girl attains maturity after her marriage, she is secluded for a period of eleven days. She bathes on the first, fourth, seventh, and eleventh days, and, on the last day the caste people are entertained with a grand feast, the expenses connected with which are met by the husband. The Katal Arayans rarely have more than one wife. A widow may, a year after the death of her husband, enter into conjugal relations with any member of the caste, except her brother-in-law. Succession is in the male line. The Katal Arayans have headmen (Aravans), whose duties are the same as those of the headmen of the Vālans. When the senior male or female member of the ruling family dies, the Aravan has the special privilege of being the first successor to the masnad with his tirumul kazcha (nuzzer), which consists of a small quantity of salt packed in a plantain leaf with rope and a Venetian ducat or other gold coin. During the period of mourning, visits of condolence from durbar officials and sthanis or noblemen are received only after the Aravan’s visit. When the Bhagavathi temple of Cranganore is defiled during the cock festival, Koolimutteth Aravan has the special privilege of entering the temple in preference to other castemen.

The Katal Arayans profess Hinduism, and their modes of worship, and other religious observances, are the same as those of the Vēlans. The dead are either burnt or buried. The period of death pollution is eleven days, and the agnates are freed from it by a bath on the eleventh day. On the twelfth day, the castemen of the village, including the relatives and friends, are treated to a grand feast. The son, who is the chief mourner, observes the dīksha, or vow by which he does not shave, for a year. He performs the srādha (memorial service) every year in honour of the dead.

Some of the methods of catching fish at Cochin are thus described by Dr. Francis Day. “Cast nets are employed from the shore, by a number of fishermen, who station themselves either in the early morning or in the afternoon, along the coast from 50 to 100 yards apart. They keep a careful watch on the water, and, on perceiving a fish rise sufficiently near the land, rush down and attempt to throw their nets over it. This is not done as in Europe by twisting the net round and round the head until it has acquired the necessary impetus, and then throwing it; but by the person twirling himself and the net round and round at the same time, and then casting it. He not infrequently gets knocked over by a wave. When fish are caught, they are buried in the sand, to prevent their tainting. In the wide inland rivers, fishermen employ cast nets in the following manner. Each man is in a boat, which is propelled by a boy with a bamboo. The fisherman has a cast net, and a small empty cocoanut shell. This last he throws into the river, about twenty yards before the boat, and it comes down with a splash, said to be done to scare away the crocodiles. As the boat approaches the place where the cocoanut shell was thrown, the man casts his net around the spot. This method is only for obtaining small fish, and as many as fifteen boats at a time are to be seen thus employed in one place, one following the other in rapid succession, some trying the centre, others the sides of the river.

“Double rows of long bamboos, firmly fixed in the mud, are placed at intervals across the backwater, and on these nets are fixed at the flood tide, so that fish which have entered are unable to return to the sea. Numbers of very large ones are occasionally captured in this way. A species of Chinese nets is also used along the river’s banks. They are about 16 feet square, suspended by bamboos from each corner, and let down like buckets into the water, and then after a few minutes drawn up again. A piece of string, to which are attached portions of the white leaves of the cocoanut tree, is tied at short intervals along the ebb side of the net, which effectually prevents fish from going that way. A plan somewhat analogous is employed on a small scale for catching crabs. A net three feet square is supported at the four corners by two pieces of stick fastened crosswise. From the centre of these sticks where they cross is a string to pull it up by or let it down, and a piece of meat is tied to the middle of the net inside. This is let down from a wharf, left under water for a few minutes, and then pulled up. Crabs coming to feed are thus caught.

“Fishing with a line is seldom attempted in the deep sea, excepting for sharks, rays, and other large fish. The hooks employed are of two descriptions, the roughest, although perhaps the strongest, being of native manufacture; the others are of English make, denominated China hooks. The hook is fastened to a species of fibre called thumboo, said to be derived from a seaweed, but more probably from one of the species of palms. The lines are either hemp, cotton, or the fibre of the talipot palm (Caryota urens), which is obtained by maceration. In Europe they are called Indian gut. “Trolling from the shore at the river’s mouth is only carried on of a morning or evening, during the winter months of the year, when the sea is smooth. The line is from 80 to 100 yards in length, and held wound round the left hand; the hook is fastened to the line by a brass wire, and the bait is a live fish. The fisherman, after giving the line an impetus by twirling it round and round his head, throws it with great precision from 50 to 60 yards. A man is always close by with a cast net, catching baits, which he sells for one quarter of an anna each. This mode of fishing is very exciting sport, but is very uncertain in its results, and therefore usually carried on by coolies either before their day’s work has commenced, or after its termination.

“Fishing with a bait continues all day long in Cochin during the monsoon months, when work is almost at a standstill, and five or six persons may be perceived at each jetty, busily engaged in this occupation. The Bagrus tribe is then plentiful, and, as it bites readily, large numbers are captured. “Fishing in small boats appears at times to be a dangerous occupation; the small canoe only steadied by the paddle of one man seated in it looks as if it must every minute be swamped. Very large fish are sometimes caught in this way. Should one be hooked too large for the fisherman to manage, the man in the next boat comes to his assistance, and receives a quarter of the fish for his trouble. This is carried on all through the year, and the size of some of the Bagri is enormous. “Fish are shot in various ways, by a Chittagong bamboo, which is a hollow tube, down which the arrow is propelled by the marksman’s mouth. This mode is sometimes very remunerative, and is followed by persons who quietly sneak along the shores, either of sluggish streams or of the backwater. Sometimes they climb up into trees, and there await a good shot. Or, during the monsoon, the sportsman quietly seats himself near some narrow channel that passes from one wide piece of water into another, and watches for his prey. Other fishermen shoot with bows and arrows, and again others with cross-bows, the iron arrow or bolt of which is attached by a line to the bow, to prevent its being lost. But netting fish, catching them with hooks, or shooting them with arrows, are not the only means employed for their capture. Bamboo labyrinths, bamboo baskets, and even men’s hands alone, are called into use.

“Persons fish for crabs in shallow brackish water, provided with baskets like those employed in Europe for catching eels, but open at both ends. The fishermen walk about in the mud, and, when they feel a fish move, endeavour to cover it with the larger end of the basket, which is forced down some distance into the mud, and the hand is then passed downward through the upper extremity, and the fish taken out. Another plan of catching them by the hand is by having two lines to which white cocoanut leaves are attached tied to the fisherman’s two great toes, from which they diverge; the other end of each being held by another man a good way off, and some distance apart. On these lines being shaken, the fish become frightened, and, strange as it may appear, cluster for protection around the man’s feet, who is able to stoop down, and catch them with his hands, by watching his opportunity.

“Bamboo labyrinths are common all along the backwater, in which a good many fish, especially eels and crabs, are captured. These labyrinths are formed of a screen of split bamboos, passing perpendicularly out of the water, and leading into a larger baited chamber. A dead cat is often employed as a bait for crabs. A string is attached to its body, and, after it has been in the water some days, it is pulled up with these crustacea adherent to it. Persons are often surprised at crabs being considered unwholesome, but their astonishment would cease, if they were aware what extremely unclean feeders they are.

“Fish are obtained from the inland rivers by poisoning them, but this can only be done when the water is low. A dam is thrown across a certain portion, and the poison placed within it. It generally consists of Cocculus indicus (berries) pounded with rice; croton oil seeds, etc.”