VS Naipaul

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A life in literature

From: FARRUKH DHONDY, ‘The world is what it is’; no one captured it better, August 13, 2018: The Times of India

From: August 13, 2018: The Times of India

From: August 13, 2018: The Times of India

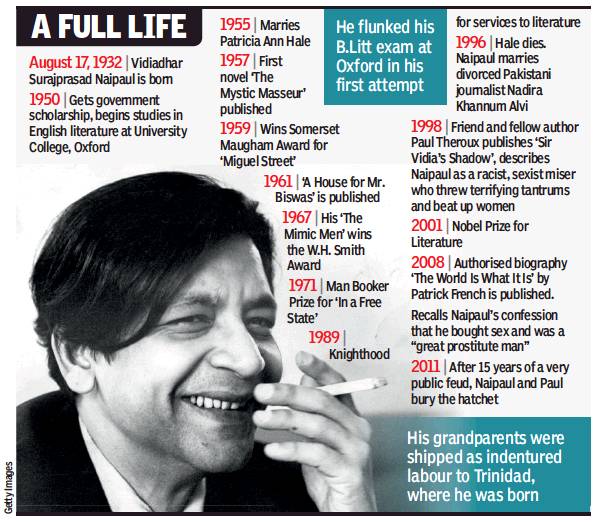

See graphic:

VS Naipaul: a timeline

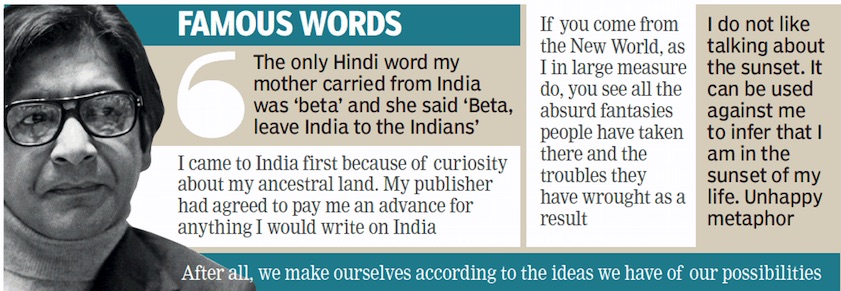

VS Naipaul- famous quotes- I

VS Naipaul- famous quotes- II

Ego and abrasiveness

August 14, 2018: The Times of India

Writers often have giant egos. Trinidadborn and Indiadescended VS Naipaul had one that may have been as elevated as the quality of his writing. The latter earned him in 2001 what many felt should have come his way much earlier given the scale of his literary achievement: the Nobel prize for literature. He had dismissed such 20th century literary greats as James Joyce and EM Forster as being of no consequence at all. Perhaps writers have to do this in a Freudian process of killing the Father to claim their place.

And Naipaul certainly had to struggle to claim his place, if you see where he came from. His grandfather was brought to Trinidad from a UP village as an indentured labourer, while his father educated himself by going to school during the day and working at night to earn a living. Naipaul may have learned the meaning of aspiration from his father, who rose from destitute origins to become a short story writer and journalist for the Trinidad Guardian.

The same aspiration drove Naipaul to escape the limitations of insular Indian society on a small Caribbean island. It’s worth remembering, however, that the postwar England of 1950, where he arrived on a scholarship at the age of 18, was a bleak place – far removed from today’s glamorous, multicultural England. Naipaul had to establish himself as a literary figure in a hostile environment by dint of the sheer quality of his writing.

It is those childhood origins and early struggle to establish himself that perhaps define Naipaul: imposing a gravitas that might seem overdone to some, informing the tragic vision that pervades his novels, and even some of his misanthropic and misogynist utterances. However, to cite Naipaul, the world is as it is, and there is no law which says great writers have to be pleasant or sympathetic people.

Naipaul saw the writer’s role as demanding a brutal honesty, a quality which made the Swedish Academy describe him as a modern philosophe when it conferred on him the Nobel Prize. And if he adopted the gloomy demeanour of an Old Testament prophet, that is qualified by his belief in the redemptive power of modernity and the value of the pursuit of happiness.

His search for literary inspiration made him travel to, among other places, India – which disappointed him severely. His famous quote on Indians defecating everywhere sounds like a wicked tweak of a storied World War 2 speech by Winston Churchill (“we shall fight on the beaches …”). But going by Swachh Bharat’s struggles, it’s not a problem India has been able to overcome more than a half century after Naipaul wrote those lines.

Part of Naipaul’s attitude was driven by nostalgia: he thought his Trinidadian origins left him without a past and affiliations, and he would find in India a large, complex, culturally vibrant post-colonial society to which he could relate. In 1990, though, he was to return and pen perhaps one of the best books written about India in the last three decades – India: A Million Mutinies Now. This is a less opinionated, quietly observant book that senses some of the energies and aspirations bubbling up beneath the appearance of passivity, red tape and postcolonial complacency.

What sticks out in this book, as in much of his later nonfiction, is his acute observation of and interest in individuals, going beyond ideology. Along with his ability to powerfully evoke time and place, this fleshes them out as real and credible people you can reach out to and be intimate with.

While Naipaul may occasionally succumb to nostalgia he is also one of its most astringent critics (perhaps because he knows it from inside). Having climbed from humble origins he does not buy the psychology of victimhood – so pervasive in India today from Hindutva proponents to their leftist critics.

His critique of India – as a place of intellectual mediocrity that values symbolism over substance and beats down anybody who thinks differently; of insular values suspicious of modernity and lacking in originality or innovation; of an inability to plan cities compensated by vacuous praise of rural pieties; of upholding a culture of poverty – is one we can overlook or dismiss only to our own detriment.

India: a contempt- hate relationship

Six months after the Babri Masjid demolition, The Times of India’s then editor Dileep Padgaonkar met V S Naipaul at the writer’s flat in London for an interview. Naipaul’s first two non-fiction books on his ancestral land, An Area of Darkness and A Wounded Civilization, had made Indians, regardless of political persuasion, angry and upset: the Left for his seeming lack of empathy and understanding for the poor and his bleak-eyed view even of India’s non-feudal past; the Gandhians because he was no respecter of their piety; the Nehruvian dreamers and Centrists because he could see no signs of progress, though he saw much corruption and in fact dismissed the country as being beyond redemption; and the Right because he acutely disliked the grip of religiosity and tradition on Indian society. By 1990, his views had changed, and in A Million Mutinies Now, he acknowledged that redemption, indeed, couldn’t be ruled out.

But his reply to a question about his reaction to the Babri’s razing showed just how deeply his thinking had changed. He’d reacted “not as badly as the others,” he said. The Mughal ruler Babar, in his view, “had contempt for the country he had conquered. And his building of that mosque was an act of contempt for the country…The construction of a mosque on a spot regarded as sacred by the conquered population was meant as an insult… an insult to an ancient idea, the idea of Ram.” In the kar sevaks who climbed atop Babri’s domes Naipaul saw “passion,” and in Hindu nationalism a “new, historical awakening” and hope for national regeneration.

As controversy erupted, the right-wing revised its opinion of this previously condescending Trinidadian Indian. Though some moderates and some Indian intellectuals — Arun Shourie for instance —had backed the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, Naipaul’s comment marked a key moment in the legitimising and mainstreaming of Hindu nationalism and, in fact, of militant Hindutva. Naipaul attracted much opprobrium of course, all the more as he accused Indian liberals of double standards, said Hindutva and Islamic fundamentalism couldn’t be equated and criticised Romila Thapar for her “Marxist” version of history; the scholar Rafiq Zakaria even described him as “a neo-proponent of Hindutva” in the tradition of R-S-S sarsanghchalaks. But Naipaul not only didn’t mind, he revelled in the row; he’d earlier always felt, unhappily, that reactions to him in India were tepid.

Though Naipaul made it clear later that history had to be finally “left behind” and that it had to be written by those with “independent minds,” the post-Babri label stuck. So much so that after Beyond Belief, the book on his travels to non-Arab Muslim countries, was out in 1998, the more passionate among Indian ‘liberals’ joined Zakaria in comparing him to Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who’d originally expounded the theory of Hindutva, and M S Golwalkar, ex-R-S-S chief and Sangh Parivar icon. He was called “Fascist” and “anti-Islamic” for criticising the poet Muhammed Iqbal and writing, at the very beginning of the book, that Islam was “not simply a matter of conscience or private belief” but made “imperial demands” and altered a convert’s core identity, his worldview, his idea of history, his sacred language (to Arabic) and his holy places (to Arab lands). This theory underlying the text, as also his description of Pakistan as little better than “a criminal enterprise,” led to him being labelled a “Muslim baiter” in that country, and similar accusations were made from within India when he yet again spoke of the “passion” he felt had animated the kar sevaks in Ayodhya.

When the Swedish Academy chose him for the Nobel Prize after the 9/11 attacks, doubts were raised about whether the choice was political. But for a man described for decades as egotistical, rude, racist, misogynistic, pitiless and worse — not just by enemies but by one-time close friend like Paul Theroux, who felt Vidia’s grasp of Islam was “naïve” and “his ignorance of Arabic… kept him from understanding the Koran” — such doubts were water off a duck’s back. In the new millennium he returned to India on more than one occasion and re-stated his position on Islam and Hinduism, eliciting strong reactions from the likes of Girish Karnad. And on his death, many remarked on Twitter that the new, emerging India had failed to bestow any real honour on Naipaul. The pot, evidently, remained stirred.

The Indian establishment and Naipaul

Sadanand Dhume, No Country For Naipaul, September 22, 2018: The Times of India

In the end, the great writer was as alien to BJP as he was to Congress

For my generation of Englishspeaking Indians reading him was an essential rite of passage. To be considered literate you had to be familiar, at the very least, with A House for Mr Biswas and Naipaul’s famous non-fiction trilogy on India. (The literary-minded ventured deeper into his oeuvre.) With the possible exception of Salman Rushdie, it’s hard to think of another post-colonial writer in English whose words have meant as much to as many Indians.

You would not guess this from the frigidity of official India toward Naipaul. Take, for instance, the correlation between the Nobel Prize and India’s highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna. The physicist CV Raman won the Nobel in 1930; twenty-four years later India included Raman among its first batch of Bharat Ratnas. Mother Teresa won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979. Her Bharat Ratna followed in 1980. The Swedes awarded Amartya Sen the Nobel for economics in 1998. As if on cue, his Bharat Ratna duly turned up the following year.

In Nelson Mandela’s case the order was reversed. The South African’s Bharat Ratna came three years before his 1993 Nobel Peace Prize, a rare case of the judges in New Delhi beating Stockholm to the punch. But so far Mother India has shown no such appreciation of the man Patrick French, Naipaul’s official biographer, once described as its “doubly displaced son.” Naipaul had established himself as one of the twentieth century’s foremost writers long before he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2001. But the odds that he will ever snag a Bharat Ratna appear vanishingly slim.

That India’s Nehruvian establishment would be allergic to Naipaul should come as no surprise. Even before visiting India from his native Trinidad, Naipaul took a dim view of India’s first prime minister. “From Nehru’s autobiography I think the Premier of India is a first-class showman with a host of third rate supporters,” he wrote in a letter to his older sister. The first two books of Naipaul’s India trilogy – An Area of Darkness (1964) and India: A Wounded Civilization (1977) – count among the most searing portraits of India’s failed experiment with socialism.

Later in life, Naipaul famously warmed to his ancestral homeland. “India: A Million Mutinies Now” (1990) predated economic liberalisation, but uncannily prefigured the possibilities it would open up, in particular for a striving middle class touched with ambition.

Despite this turn, Naipaul remained firmly on the wrong side of most of India’s intelligentsia. Perhaps the playwright Girish Karnad’s peevish rant at the 2012 Tata Literature Festival in Mumbai best captures the dominant strain of Indian anti-Naipaul opprobrium. Karnad attacked the festival’s organisers for giving Naipaul a lifetime achievement award despite his alleged “rabid antipathy to the Indian Muslim.” (Never mind that Naipaul was married to a Pakistani Muslim, or that he hardly needed a literature festival’s imprimatur to validate his work.) It’s easy to dismiss the caricatured version of Naipaul presented by some of his critics, but at least their responses to him are easily comprehensible. Why would India’s clannish leftist intellectuals choose to celebrate an author who spent a lifetime gleefully shattering their most dearly held pieties?

On the face of it, the Bharatiya Janata Party government’s failure to honour Naipaul is much more intriguing. After all, it would only take a little cherry-picking from his biography to conjure up an authentic intellectual hero for the Hindu right.

As French recalls, Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul was named for a Chandela king, from the dynasty that built the Hindu temples of Khajuraho. Under less than ideal circumstances – first in Trinidad and then in England – he preserved a sense of himself as a high-born (Brahmin) Hindu.

The destruction of the Vijayanagar Empire by medieval Islamic armies moved Naipaul deeply. His mistrust of religious conversion – Christian and Muslim alike – sprung from a Hindu sensibility. Most controversially, Naipaul saw merit in the 1992 destruction of the Babri Masjid. As he put it, “one needs to understand the passion that took them on top of the domes.”

But if you look more closely Naipaul is in fact as awkward a fit for BJP as for Congress. Viewed through an Indian political prism, his life’s central quest – to become a great man of letters in the heart of the Empire – seems outdated to the point of quaintness. Naipaul was faithless in a religious sense; it’s hard to imagine him getting worked up over the food on his neighbour’s plate. He remained famously aloof from the din of day-to-day politics. He voted only once: for Margaret Thatcher.

Moreover, as French points out, in a time of intellectual relativism Naipaul stood for “high civilization, individual rights and rule of law.” In an India marked by low rent hagiography and hysteria about imagined enemies, these hardly seem like qualities in demand.

Famous works

From: August 13, 2018: The Times of India

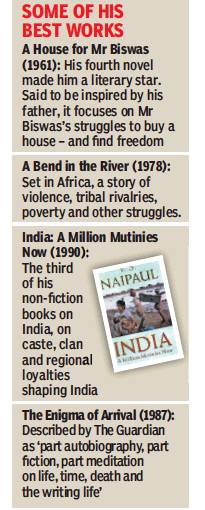

See graphic:

Some of famous works of V S Naipaul

Controversies

NO STRANGER TO CONTROVERSY, August 13, 2018: The Times of India

Naipaul once famously said, “If a writer doesn’t generate hostility, he is dead.” He lived by that dictum, never shying away from a fight and stirring up one furore after another with biting, hard-hitting words. A sample

I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not. I think [it is] unequal to me.”

(ON BEING ASKED IF ANY WOMAN WRITER WAS HIS LITERARY EQUAL)

Africa has no future... Africans need to be kicked, that’s the only thing they understand

It [Islam] has had a calamitous effect on converted peoples. To be converted you have to destroy your past, destroy your history. You have to stamp on it, you have to say ‘my ancestral culture does not exist, it doesn’t matter’.”

The Taj is so wasteful, so decadent and in the end so cruel that it is painful to be there for very long. This is an extravagance that speaks of the blood of the people.

Indians defecate everywhere. They defecate, mostly, beside the railway tracks. But they also defecate on the beaches; they defecate on the hills; they defecate on the river banks; they defecate on the streets; they never look for cover.

Tributes

Farrukh Dhondy’s tribute

His Quest Was To Turn The Imagined Into The Seen

Perhaps all those who contribute to the world divide it. I am sure Galileo was not very popular with medieval theologians who insisted on believing that the earth was the centre of the universe. Darwin wasn’t the darling of those who thought God created all creatures in those six days. Mahatma Gandhiji was reviled by Churchill for demanding decolonisation and setting the world on a new political course.

So it was, I think, with Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul. No one needs to be reminded that people from all over the world reviled and attacked him. Girish Karnad did, in a famous episode which I am compelled to rehearse later. Then fellow Nobel prize winner Derek Walcott who called him ‘VS Nightfall’ and said he was a racist.

And then there are thousands of people whose nationalism overcomes the evidence of their senses – those who deny that Indians defecate and urinate openly in the streets, those who object to it being pointed out to an African potentate that black magic cannot make you have two bodies which are simultaneously present in France and at a dinner table in Ghana; those who couldn’t see that Haiti was a degraded civilisation with more poverty, murders and corruption per square mile than in Hades…. And, dare one say it: those who denied or covered up the fact that the Muslim and then Mughal conquests and governance of India often perpetrated brutality and even partial genocide through the compulsions of war or the contempt generated by the diktat of religion.

Girish with the best of motives, in a famous speech at a Mumbai literature festival characterised Vidia as an Islamophobe. He provided a packed audience with his contentions and the evidence for his prosecution. It may have convinced some, but knowing Vidia I knew it was far from the truth. Vidia wasn’t antagonistic to any theological formation. He may have found certain practices of, say, Christians, symbolically worshipping an instrument of capital punishment distasteful. It would, if the messiah were condemned to death today, be like using the electric chair as a symbol of salvation. Vidia never, in writing or verbally, attacked any theology. As far as I could tell, he had a respect for Hindu ritual but wouldn’t engage with its tenets.

He wasn’t anti-Islamic or anti-Muslim. He married a Pakistani Muslim and though I’ve not seen Nadira, Lady Naipaul, saying her prayers or going to the mosque, she certainly objects to any blasphemous references to the Prophet. Vidia has formally adopted her two Muslim children and is grandfather to their offspring. What Vidia has written about, vehemently and with condemnation, is what he believes was a distortion of history by the Nehru-Gandhi version of it , which had the noble political purpose of glossing over Muslim atrocities and genocide of sections of Hindu society in the interests of religious harmony in India. Vidia’s inclination to tell the truth, to draw back the carpet under which this history has been swept is, understandably interpreted as divisive.

And so to Derek Walcott’s contention, backed by very many, that Vidia’s critical insights in his writing amount to racism. In his book A Writer’s People, Vidia writes about coming upon Walcott’s early poems and being fascinated by the fact they existed. As Vidia progresses and confronts the world of writing he sees and provides insights into the limitations imposed on writers by the worlds they come from or the ones they embrace. It leads him to analyse the scope and limitations of West Indian writers whose work he characterises, sometimes negatively. Walcott was obviously not pleased.

In the same book Vidia does not hesitate to apply the similarly if broader strictures to British writers and to his sometime friend Anthony Powell. The book is in no sense colour-conscious and in itself provides no evidence for calling him a racist.

Perhaps those that do base their arguments, if they can be called arguments, on his books about Africa, the Caribbean and, equally importantly, the Islamic world of Iran, Pakistan and other non-Arab nations which have adopted the faith.

Vidia’s distinction and uniqueness as a writer is to address the countries and continents he explores and describes through the lives and discourse of people he encounters in the first half century after the collapse of colonialism.

The writing takes many forms, none of them copies of anything that has gone before. Throughout his conversations with me, for formal published interviews or relaxed guppshupp (he would have hated the description) between friends, he would extol the fresh and the underivative.

He once read me a passage from Pickwick Papers and said nobody had looked at that small segment of the world in that way. He thought it was wonderful. He then picked up A Tale of Two Cities and read a paragraph or two of description from it, remarking that it was inexact, cliched and derived from Dickens’ earlier books. I pointed out that Tale was the only book written at a historical distance from Dickens’ own life. Vidia said it was not seen but imagined.

Rahul Singh on Naipaul

RAHUL SINGH, A man always true to himself, August 13, 2018: The Times of India

I first met Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul in the mid-1960s, when he made his initial trip to India, resulting in his “An Area of Darkness.” He was still in his twenties. The book offended a lot of Indians for its rather unflattering portrayal of the land of his forefathers. His observation, during a train journey, of people squatting near the railway tracks, mug or lota of water in hand, baring their bottoms, while doing their morning business, upset many. The trouble is that it was true then – and is still true today, half a century later. Naipaul had this knack of uncovering uncomfortable truths in his writings. And it came essentially from him being an outsider. Only an outsider, with keen perception and profound insights, could reveal what Naipaul did.

His target was mainly Third World societies, which he disparagingly labelled as being “half-formed”. He became a lightning rod for criticism by those he hurt. But he did not care. He laughed at his critics. But even they grudgingly admired his exquisite prose and his mastery over the English language. He once revealed to me that after he had started working on a book, he only wrote 200 to 300 words a day, choosing every word with utmost care and reworking passage after passage. One of his editors confessed that she rarely changed anything in the manuscript he submitted to her, so carefully and precisely thought out was every word.

He led a complex private life. When he first came to India he was married to an English lady, Pat. On a subsequent visit he had acquired an Argentinian mistress, Margaret, who broke up her marriage for him. In return, he gifted her an apartment in Buenos Aires. He then met Nadira, a Pakistani Muslim, and dumped Margaret, who was devastated. In between, he admitted he frequented prostitutes.

His book on Islam, “Among the Believers” infuriated much of the Islamic world. Though he was on the short list of the Nobel Prize for several years, opposition to his candidature by prominent Muslim leaders apparently stalled his getting the award. But the terrorist attack on New York’s World Trade Centre, changed the public mood, and soon afterwards, he got the coveted prize. The Hindutva brigade rejoiced when he lent support to the destruction of the Babri Masjid, calling it a “re-ordering of history”.

But it is difficult to put a label on Naipaul. Anti Islam? But he married a Muslim. He simply wrote what he saw. And if those insights hurt, too bad! As Shakespeare put it, “To thine own self be true, and it must follow, as the night, the day. Thou canst not then be false to any man.” That was Vidia Naipaul, true to himself.