Urdu literature

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History of How Urdu Began

Much has been written on the origin of Urdu. The word ‘urdu’ itself is Turkish and means ‘army’ or ‘camp’; our English ‘horde’ is said to be connected with it. The Muslim army stationed in Delhi from 1193 onwards was known as the Urdu or Urdu-i-Mu’alla the Exalted Army.

It is usually believed that while this army spoke Persian, the inhabitants of the city spoke the Braj dialect of Hindi. There is no reason however to think that Braj was ever the language of Delhi. The people of the capital spoke an early variety of that form of Hindi now known as Khari Boli, which is employed today in all Hindi prose and in most Hindi poetry. The idea that the army spoke Persian also requires reconsideration.

Mahmud of Ghazni annexed the Punjab in 1027 and settled his army of occupation in Lahore. The famous scholar, Alberuni of Khiva (973 1048) lived there for some time while he studied Sanskrit and prosecuted his researches into Hinduism. Mahmud’s descendants held the Punjab till 1187, when they were defeated by their hereditary foes under Muhammad Ghori who had already sacked Ghazni. The first sultan of Delhi was Qutb-ud-Din Aibak, a native of Turkistan, but a servant of Muhammad Ghori and afterwards his chief general.

He captured Delhi in 1193 and on the death of his master in 1206 took the title of Sultan. From that time foreign troops were quartered in the city, Urdu is always said to have arisen in Delhi, but we must remember that Persian-speaking soldiers entered the Punjab and began to live there, nearly 200 years before the first sultan sat on the throne of Delhi.

What is supposed to have happened in Delhi must, in fact, have taken place in Lahore centuries earlier. These troops lived in the Punjab; they doubtless inter-married with the people and within a few years of their arrival must have spoken the language of the country, modified of course by their own Persian mother tongue.

We can picture what happened. The soldiers and people met in daily intercourse and needed a common language. It had to be either Persian or Old Punjabi, and the people being in an enormous majority, their language established itself at the expense of the other.

For some time the soldiers continued to talk Persian among themselves and the local vernacular with the inhabitants of the country; but ultimately Persian died out, though it continued to be the language of the court, first in Lahore, and later in Delhi, for hundreds of years after it had ceased to be ordinarily spoken in the army.

In the Persian which the invaders used there were many Arabic and a few Turkish words; a large number of these were introduced into India.

What happened in Lahore and Delhi resembled in many points what was happening in England after the Norman conquest.

The Normans, speaking a dialect of French, came into an Anglo- Saxon-speaking country and made French the court language. Though they greatly influenced the speech of the conquered country, yet within three centuries they had lost their own language, and England today speaks English, blended, it is true, with French.

The changes produced in English by the coming of the Normans have probably been exaggerated, but in any case they were greater than those produced in Punjabi and Hindi by the Muslim army.

Apart from the incorporation of many loan words the influence was remarkably small. These languages remained practically unchanged in their pronouns, verbs, numerals and grammatical system. The chief change was in vocabulary. In all this English corresponds very closely to Urdu.

Muhammad Ghori seized the Punjab in 1187 and his troops under Qutb-ud-Din Aibak, after consolidating their position, swept on to Delhi, but they cannot have left a hostile Muslim army in the rear.

We may be certain that the descendants and successors of the original invaders joined them, and that the two armies marched together to Delhi, which was taken, as we have seen, six years later. When, 12 years later still, the new emperor was installed in Delhi, a large proportion of his soldiers must have spoken by preference a language very like what we think of as early Urdu (the remainder speaking Persian). The basis of that language was Punjabi as it emerged from the Prakrit stage, and it cannot have differed from the Khari of that time nearly as much as the two languages differ today.

The important fact is that Urdu really began not in Delhi but in Lahore, and that its underlying language was not Khari (much less Braj, as often stated), but old Punjabi. Later on this first form of Urdu was somewhat altered by Khari as spoken round Delhi, but we do not know that Braj exercised any influence at all.

The formation of Urdu began as soon as the Ghaznavi forces settled in Lahore, that is in 1027. At what time they gave up Persian and took to speaking Punjabi Urdu alone, we cannot tell, probably it was a matter of a very few years. 166 years later the joint Ghori and Ghaznavi troops entered Delhi. In a short time Urdu was probably their usual language of conversation.

We must therefore distinguish two stages: (1) beginning in 1027, Lahore-Urdu, consisting of old Punjabi overlaid by Persian; (2) beginning in 1193, Lahore-Urdu, overlaid by old Khari, not very different then from old Punjabi, and further influenced by Persian, the whole becoming Delhi-Urdu.

When Muhammad Tughlaq invaded the Deccan and founded Daulatabad (1326), and 21 years later when Ala-ud-Din Bahmani rebelled against him and became the first ruler of the Bahmani dynasty, the Muhammadan troops who accompanied them spoke Urdu as their mother tongue, and the language which grew up among the Marathi, Telugu and Kanarese- speaking inhabitants who became Muslims, was not Persian but Urdu.

It is worthy of note that whereas in the north the invaders gave up their own tongue and adopted Urdu, their successors and descendants managed to impose that language, now their own, on a large part of the Deccan, where today it is spoken by nearly three million people.

Early History of Urdu We have no accurate knowledge of spoken Urdu in the early years of its existence. Amir Khusrau (c.1255-1325) tells us in his Persian works that he wrote a great deal in ‘Hindavi,’ but only a little has come down to us; and what we now possess, perhaps 1,000 lines, has doubtless been considerably altered in the passage of time, so that we cannot regard it as correctly showing the speech of his day.

We must however emphasise the fact that he did compose literary works in Hindi or Urdu, perhaps both, and that nearly 200 years ago the poet Mir Taqi accepted as genuine some of the verses which we have today. We know this because Mir refers to them in his anthology.

The word ‘Hindi’ is used in both a wide and a narrow sense. In the wide sense it includes the languages spoken in Bihar, the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, Central India, Rajputana and the S.E. Punjab as far as Ambala. One might include Kumaon and Gadhval. In the narrow sense it means Hindi proper, the chief dialects of which are Braj and Khari.

The first writers of Hindi wrote principally in Bihari, Avadhi, Braj and Rajputani; languages which were used for both composition and conversation. Muslim authors occasionally employed one of these, but more commonly Persian. Khari, though widespread as a conversational medium, was not much used for literature.

Urdu is always said to have arisen in Delhi, but we must remember that Persian- speaking soldiers entered the Punjab and began to live there nearly 200 years before the first sultan sat on the throne of Delhi.

Indeed with the exception of Amir Khusrau’s few hundred lines just mentioned, which are mostly in Braj, and the works of the poet Sital (c.1723), we have no work in it till we come to the verge of the 19th century.

The Urdu branch of Khari has a different history. Mi‘rajul Ashiqin; a tract by Banda Navaz, which has recently been printed, and is probably genuine, belongs to the end of the 14th century.

Seeing that the author left the Deccan when he was 15 and lived thereafter in Delhi, not returning to the Deccan till he was an old man, we may take his prose as showing the Delhi idiom of that time. In the 15th century there is Shah Miran Ji of the Deccan, who has left four extant works, and from that time the stream of literature goes on ever widening and deepening.

We must therefore revise our thoughts of both Khari and Urdu. Khari is contemporary with Braj and Avadhi; its beginning may be put at AD 900 or 1000. The commencement of Urdu may be dated, any time after 1027, when the Muhammadan army of occupation began to live in Lahore.

Khari as a spoken language has a continuous history of nearly a thousand years; as a literary language, if we omit Amir Khusrau and one or two other authors, it dates from the end of the 18th century.

It is difficult to distinguish precisely between Khari and Urdu. For practical purposes the distinction lies in the fact that Khari uses very few, and Urdu very many, Persian and Arabic words.

Some people, both Europeans and Indians, have made the use of Hindi or Persian metres the touchstone, but that distinction can be applied only to poetry; it is inapplicable to prose. In poetry, too, some authors, while not varying their language, have employed now Hindi metres, and now Persian. Even at the present day there are poets who sometimes write Urdu poetry in Hindi metres.

There has been a strange reversal of the decrees of fate. The despised Khari language, confined to conversation, and considered unfit for poetry, was not used for serious literary purposes, except by Sital and perhaps Amir Khusrau, till near 1800; so much so that even today some persons, not realising that it has had a vigorous existence among the common people since the time when it took the place of Prakrit, think that it was invented by Insha Allah, Sadal Misr and Lallu Lal.

In the Hindi sphere it has now turned out its rivals, and will soon be the only survivor so far as literary work is concerned, while in its Urdu form it has been for centuries the medium of a prosperous and growing literature.

It is important to remember that in the middle of the 14th century there was no real difference between Delhi Urdu and Dakhni Urdu, but with the establishment of the separate Bahmani dynasty the two dialects began to diverge.

Urdu literature in its early stages was much more conversational and simple than it was in later years. Probably for that reason it resembles to a surprising degree the spoken language of today. This resemblance must not be used as an argument against the genuineness of an early poem or prose work.

It shows merely that the author wrote the language as he spoke it. In later years men writing artificially and following foreign models produced works which, divorced from everyday idiom, differ widely from the Urdu which we know now. To take two instances. The Dakhni poems of Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah before 1600, and the beautiful Dakhni poem Qutb Mushtari written by Vajhi in 1609, are easier to read than Shah Nasir’s writings in the 19th century.

The Name ‘Urdu’ An important question is how the word ‘Urdu’ came to be applied to a language. We have seen that the soldiers in Delhi at a very early date gave up the use of Persian among themselves and began to speak a modified form of the vernacular.

In Delhi this form of speech, to distinguish it from the usual Khari Boli (and probably also from Persian), was called Zaban-i-Urdu, the language of the Army, or Zaban-i-Urdu-i-Mu‘alla, the language of the Exalted or Royal Army. As the soldiers and the people intermixed and intermarried, the language spread over the city into the suburbs and even into the surrounding district.

It was natural to keep up the separate name to distinguish it not only from the unmixed vernacular of the people, but also from the Persian of the court. This double distinction is not unimportant. It is possible, too, that in time the name served to mark still another distinction, viz. between the speech of Delhi and that of Lucknow.

It is supposed that gradually the word ‘zaban’ was dropped, and ‘Urdu’ came to be used alone.

In this explanation there is a difficulty. Though the royal camp was established in Delhi during the time of Qutb-ud-Din Aibak in 1206, the earliest known example of the employment of the word ‘Urdu,’ standing by itself and meaning the Urdu language, is in the poems of Mushafi, 1750-1824, which are unfortunately updated, and in any case have only in part been printed. Gilchrist uses it in his Grammar (1796).

The earliest examples of the phrase, Zaban i Urdu, the language of the camp or the Urdu language, are in Tazkira a Gulzar i Ibrahim by Ali Ibrahim Khan (1783) and in Mushafi’s Tazkira a Shuara a Hindi (1794). In this title we must note the word ‘Hindi’ (meaning ‘Urdu’). The expression Zaban-i-Urdu-i- Mu‘alla (e Shahjahanabad Dihli), the language of the

Royal camp, or the Exalted Urdu language (of Shahjahanabad, Delhi) occurs in the anthology Nikat ush Shu’ara by Mir Taqi (1752).

In Qiyam ud Din Qaim’s anthology Makhzan-i-Nikat (1754) we find muhavira-i-Urdu-i-mu‘alla, the idiom of the Royal Camp. Arsh, the son of Mir Taqi, speaks of himself as Urdu-i-mu‘alla ka zabandan, one well acquainted with the Urdu-i-mu‘alla language. His date is unknown, but he seems to have been born in Mir’s old age.

Now the earliest of these is five centuries after the foreign army had settled in Delhi; and we naturally ask why during all this long period the language never received the name ‘Urdu,’ and why people suddenly thought of that name after the lapse of so long a time, when it had ceased to have any particular meaning.

This period of 550 years could perhaps be reduced; it has been claimed, but not proved, that the royal camp in Delhi was not known as the Urdu till the time of Babur, who came direct from Turkistan with a Turki force in 1526. It is a doubtful point. We may admit that before his time the foreign recruits had nearly all been Persian speakers or descendants of Persian speakers. But on the other hand the word ‘Urdu’ for army had been in Persian since 1150, for it is found more than once in the Jahankusha of Javaini with that meaning.

The first example of it in India is said to be in the Tuzuk-i-Baburi, compiled by the Emperor Babur himself in 1529. But even if we accept these later dates for the first occurrence in India of the word ‘Urdu’ with the meaning of army, we still have to account for the fact that for 226 years, from 1526 to 1752, no one seems to have thought of calling the language by that name, and that it was only after 1752 that this was done.

It is almost incredible that none of the historians of the Mughal period ever used the name; yet such seems to have been the case.

Urdu literature in its early stages was much more conversational and simple than it was in later years. Probably for that reason it resembles to a surprising degree the spoken language of today. This resemblance must not be used as an argument against the genuineness of an early poem or prose work.

The language, as spoken, was generally called Hindi; when employed for literary, that is poetical, purposes it was known as Rekhta or Hindi. Amir Khusrau and Sheikh Bajar (d.1506) speak of Zaban-i-Dihlavi, the speech of Delhi while Vajhi in Sab Ras (1634) calls it Zaban i Hindostan, the language of Hindustan.

But no one in the early days spoke of ‘Urdu.’ Even in the end of the 18th century it was an uncommon word. People continued to talk of Hindi and Rekhta. As late as 1790 Abd ul Qadir, in the preface to his Urdu translation of the Quran, said he was translating not into Rekhta but into Hindi.

One interesting detail is still sub judice. It has been asserted that the Persian dictionary, Mu‘ayyid ul Fuzala (1519) uses the phrase, ‘in the language of the people of the Urdu.’ But it is claimed on the other hand that the words are not found in good MSS of the dictionary; and the MS in the British Museum does not appear to contain them.

Even if it did, ‘Urdu’ would not here be the name of a language. It is a fact worth noting that the word ‘Urdu’ is not given in this dictionary at all with any meaning, either ‘army’ or any other.

Possibly the explanation of the problem is that Zaban-i-Urdu, the speech of the camp, or some equivalent phrase, was in conversational use from the earliest times, and that gradually, centuries later, it was admitted to books, while the use of the word ‘Urdu’ alone, without zaban, was still later. But the subject requires further investigation.

A LITERARY LEGACY

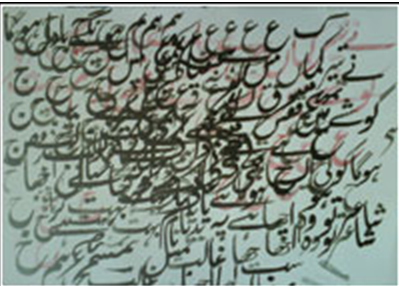

(No matter how one might try Urdu is irrepressible Let Allah be its protector. The Urdu tongue is a whole hand breadth)

Urdu has been and remains a hardy survivor. It does not just survive but also thrives and grows from strength to strength regardless of the odds. It is verily an indestructable fibre endowed with a rare capacity to adapt itself to an ever-changing world, without losing its real essence. Urdu is tenacious. Its tenacity can only be matched by its adaptability to an ever-changing environment. It’s the language of the gypsy — born landless — yet has struck its roots too deep and strong to be uprooted. It has travelled all the way from North to South, East to West with ever-changing names, accents and idioms and yet retains its inherent genre and character.

The reprint of Grahame Bailey’s History of Urdu Literature is a valuable contribution to the subject that has been relegated to a somewhat insignificant slot despite its vital importance as the national language of a country as big as Pakistan. Pakistanis, let’s painfully accept, are doing little to place Urdu on the high pedestal it deserves regardless of the increasing gravitational pulls of the regional languages including Punjabi, Sindhi, Balochi and Pushto. Punjab, the largest publication house practitioner and promoter of Urdu, is gradually showing a preference for Punjabi as a spoken language, without in any way diminishing its role in promoting Urdu as a literary language.

Without prejudice to the status and growth potential of the regional languages, the importance of a single national language can hardly be exaggerated. The growing tendency to speak the local language and write in Urdu, though perfectly natural, unless judiciously balanced, can create — in fact has created — a sort of a split mind and the confused thinking that goes with it.

Added to this is the increasing use of English as the medium for the study of science and technology, even more so as a recognised status symbol. The ‘O’ and ‘A’ levels texts, especially of history and literature have created a class system to set the English-speaking students apart from the madressa types. Apart from excellence in English, the courses of study followed and the academic years (examination schedules) observed produce a class distinction that is distasteful and inconsistent with a shared citizenship.

The Urdu wallas, no matter how promising and diligent, are often placed a notch below the English wallas not just socially but also in terms of jobs opportunities.

While it would be unfair to belittle the value of Bailey’s work as a valuable asset scholars of Urdu literature and history, its relevance to the language’s current post-partition status, particularly in India and Pakistan, its native homes, remains essentially pedantic.

Except for research dissertations in learned journals, not much seems to have been attempted on the fate overtaking Urdu after 1947. Whose language is it? Does it belong to Delhi or Luknow, Deccan, Bihar or Bollywood? It is hard to guess. However Urdu is here to stay and flourish as the lingua franca. And let there be no doubt about that.

Urdu helped to throw open the iron-clad gates of India to the rest of the world. While the Taj Mahal stands out as the gem of Mughal art and architecture, Urdu dazzles as the jewel in the crown — both as an invaluable literary medium and the lingua franca or the Khari Boli.

The word Urdu (meaning lashkar or troop) emanated from the invading Muslim armies of the sultans and the Mughals who were quartered in the city of Delhi. The soldiers and local populace met in daily intercourse and needed a common language to communicate. It was this need that gave rise to the birth and development of Urdu.

Amir Khusro used Urdu in both a ‘narrow’ and ‘wider’ sense. The wider sense includes Ganga-Jamni Urdu whereas Hindi or ‘Hindvi’ comprising dialects like Braj and Khari. Khari uses very few Persian words, unlike Urdu especially in its pre-modern classical mode which is almost an Urdu or Hindised version of Persian.

‘By a strange reversal of the decrees of fate’, Bailey says, Khari Boli, the spoken language of the bazaar took the better of the chaste Urdu-i-Mau’alla.

The relevance of history as a record and reappraisal of the past is absolute for the guidance of the present and the future. What is more important, however, is to place on record and analyse the current developments and challenges beyond what is provided in the available history books.— A. R. Siddiqi

Books & Authors reserves the right to edit excerpts from books for reasons of clarity and space.

The book was first published in 1932 and regards the formative Deccan period as being important for the development of the Urdu language and equally for its poets.

T. Grahame Bailey obtained his D.Litt. from the University of Edinburgh and became a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. He retired from this position in 1940 and died two years later.

Excerpted with permission from A History of Urdu Literature

By T. Grahame Bailey

Introduction by Muhammad Reza Kazimi

Oxford University Press, Karachi

115pp. Rs250

Urdu literature, historiography

An exhaustive journey into literary history

By Intizar Hussain

With the plan of an exhaustive history of Urdu literature in view, Jameel Jalibi embarked on a long journey through centuries of the Indo-Pak subcontinent. The first volume, as the starter of this ambitious plan, came out in the late seventies of the twentieth century. It was soon followed by the second volume which in its turn was subdivided into two volumes, and published in 1982.

Now with the advent of the twenty-first century, we have from him the third volume of the series. But he is still in the middle of his journey as the present volume covers only half of the nineteenth century. The other half is to be covered in the fourth volume. But that is not the end of the story.

Beyond the nineteenth century lies the tumultuous twentieth century. It may too refuse to be contained in one volume. So the project is long and arduous. May Jalibi live long so as to be able to achieve the completion of this ambitious project. He, on his part, seems determined to complete it in accordance to his plan. Great works ask for extraordinarily devoted souls. Urdu is fortunate to have one such soul within its fold.

But how does this history stand distinguished from those previously written? Is it volume alone which makes the difference? Or is it the detailed study of each period and of writers belonging to the period, which qualifies it to be treated as a distinctive literary history? Of course this too is a distinctive feature of this history. But the real basis of distinction is something else. In our literary histories written so far literature, more particularly poetry, had been treated as an independent phenomenon in the social environment of our society. Only occasionally casual references were made to the prevalent social conditions.

Here in this case the very conception of a literary history is different. Here the concept is that literature is not an isolated phenomenon in the history of a society. On a deeper level it has links with what is going on in society. So for a correct understanding of literature it is necessary to keep the socio-political situation of that age in view.

Literary trends can best be understood when seen in the perspective of socio-political and cultural conditions of that period. In his preface to the present volume Jalibi has expressly said that he has tried to seek connection of literature with society, culture, and linguistic evolution and make a study of it in totality. And that “what was the peculiar spirit of that age, which provided an incentive for literary creation.”

The corollary to this concept is that prose and poetry should be studied jointly. “The reason is,” says he, “that prose and poetry both are equally influenced by social and cultural conditions. They both can better be understood when seen in the perspective of their times.”

So in the present volume, which deals with literary trends during first half of the nineteenth century, Jalibi begins by looking firstly at the political situation and then at the changing social and cultural scenario. Traditional society, as he perceives, was in tatters. The validity of age-old customs and rituals was being questioned. A need for social reforms was being felt, giving rise to certain reformative movements both among the Hindus and the Muslims.

With this awareness of political, social and cultural situation, he turns to the literary scene as it emerged during those times and surveys it in that perspective.

Jalibi’s history stands distinguished also because of its refusal to share the prejudices our literary historians had in general inherited from the elitists of Delhi and Lucknow. Because of its eliticism, the literary world of old Delhi and Lucknow was simply incapable to appreciate and recognize poets like Jafar Zatalli and Nazir Akbarabadi. Jafar was perhaps the worst sufferer as the literary historians of the later periods too appeared sharing the same prejudice against him.

But Jalibi chose to take a serious notice of this poet for two reasons dear to him. One reason being the acute socio-political awareness of the poet, which made his verse reflective of the deteriorating conditions of that age. The other reason lies in his linguistic innovations, which inform his poetic diction. This helps us to understand the evolutionary process Urdu was passing through at that stage of its development.

In contrast to Jafar Zatalli and Nazir Akbarabadi, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, with his passion for fine arts, invited a different kind of prejudice. And Jalibi tells us that the Britishers and some papers at their behest launched a vilification campaign against him. In fact they were in search of some justification for dethroning him and taking Oudh completely in their control. They exploited conservative Muslims’ prejudice against fine arts and interpreted his involvement in arts as signs of his decadence and moral degradation.

Wajid Ali Shah figures prominently in the present volume of Jalibi’s book. In reply to his character assassination, Jalibi has brought to our notice the positive aspects of his character and has discussed in detail his contributions to different branches of arts and literature.

So one distinctive feature of this history is its attempt to fight those cultural prejudices and misconceptions which stand in the way of the understanding of our literary tradition and a number of such trends which have enriched this tradition.

This history has also refused to treat Lucknow and Delhi as two different schools of poetry. In the estimation of this history it is one and the same tradition of poetry extending from Delhi to Lucknow.

So it is a history conceived differently and exhaustively.

Urdu novel, impact of English ideas

February 04, 2007

EXCERPTS: Novel ideas

Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah’s PhD thesis which, in 1940, made her the first Muslim woman to earn a doctorate from the University of London.

Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah traces the genesis of the Urdu novel.

The contact with English literature has had a profound and far-reaching effect on Urdu. With the impact of western culture came new ideas and ideals, a new outlook on life, and a new conception of values. It revolutionised thought and changed not only the superficial outlook on life but basic moral values as well. In short, contact with English life and literature brought about the same changes in India as the Renaissance had done in Europe. In fact this period is called, and rightly so, the Renaissance of Urdu. There is nothing like a shock to bring about the flowering of genius, and a new leavening from time to time is a very beneficial thing for any society.

Urdu poetry had reached its peak of achievement on the lines it had chosen in the field of the ghazal and qasida. Even in the marsia and the masnavi all that could be done had been done. The language had been polished and purified, until it shone like burnished gold. Every thought and idea that could be culled from mysticism and from philosophy had been culled and distilled and presented, not once but many times; nothing original remained to be done in that sphere any more. A further purifying of language and evolving of rhetorical rules would only have weakened it, and attempts to present thrice presented thought in new garb would only have resulted in artificiality.

The time was ripe for a change, for the exploration of new realms of thought and for the adoption of new ways of expression. And the western influence did both.

Up until then, the stock of thought was an admiration for contentment, an exaltation of a fatalistic attitude towards life, a submission to suffering and unworldliness, while the noble-minded poets dealt solely with love and passion often in its less admirable aspects. The crumbling of the Moghul Empire and the destruction of their own culture imbued poets like Ghalib and Mir with a feeling of utter melancholy and despair, which found expression in poems which, for sincerity, depth of thought and for sheer literary merit, remain unequalled. But still the thought expressed in them was akin to the thought and feeling of what could be called the ‘Age of Ghazal’ in Urdu literature.

But the contact with the West brought with it an entirely new set of ideas. The ideals of unworldliness and concern with the ultimate good of the soul gave place to a desire for making the most of this world and achieving success. A spirit of struggle, a spirit of adventure and a desire for achievement took the place of resignation and the patient bearing of one’s lot.

Robust feelings such as these did not find adequate expression in the lilting couplets of the ghazal. So the musaddas and masnavi came into their own as they gave greater scope for continuous thought. Love lyrics gave place to narrative and descriptive poems. Wordsworth had a great influence. Nature which had so far been ignored, and only incidentally brought in (as for example in the qasida) as a background, became a very popular subject and patriotic poems became the order of the day.

This influence brought about a more realistic attitude towards life. Urdu poets had so far lived in realms of fancy and imagination; now they are coming down to the reality of life. So far, their woes had been coldness of an imaginary beloved, nor were they face to face with the (less poetic) misery of existence.

Prose naturally is a more suitable vehicle of expression for mundane thoughts of life and poetry. Hence the age of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and Hali, or the Renaissance of Urdu literature as it has been called, saw the development of prose to its final perfection. The birth and popularity of prose were the natural complement of the general attitude of realism that was produced under western influence. But only in this indirect way was western influence responsible for the development of prose; it had also a direct influence in bringing it about. It was under the auspices of the Fort William College, Calcutta, that the first words of prose fiction were written.

In order to enable the employees of the East India Company to learn the vernaculars, the Fort Williams College, Calcutta, was founded in 1800, and Dr Gilchrist placed at the head of it. Dr Gilchrist composed an Urdu grammar (generally considered to be the first; but there are some doubts as to the correctness of this statement as an Urdu grammar in Latin is supposed to have existed before this) and an Urdu dictionary.

He travelled in the regions where the choicest Urdu was spoken, and from Delhi, Lucknow, Cawnpore and Agra he collected a band of men who were masters of Urdu idiom. He set them to translate into Urdu prose stories from Persian and Sanskrit. As the object was to get, as quickly as possible, books which could be used as textbooks for teaching young Englishmen Urdu, he had them written in easy flowing prose and not in the heavy ornate style which was so popular

Amongst the books translated there were manuals of conduct, historical pamphlets and books of instruction. In fiction there was Bagh o Bahar by Mir Amman, Araish i Mahfil by Sher Ali Afsos, Nasr i Benazir by Bahadur Ali Husaini, Mahzab i Ishq by Nihal Chand Lahauri, Shakuntala and Singhasan Battisi by Kazim Ali Javan and Lallu Lal in collaboration. They enjoyed an immense popularity, and are still read with pleasure and are included in the Urdu curriculum of most colleges and schools.

Though translations, they are part and parcel of Urdu literature. They popularised prose and developed a taste for it, whereas until then poetry alone was appreciated, and thus prepared the way for the coming of the novel.

Bagh o Bahar (1801) is the first of these translations and deservedly the most popular. Its language is easy and flowing, without any of the encumbrances of rhetoric; the manner of story-telling is intimate so that the reader feels that he is being taken into confidence and is listening to rather than reading a story.

The characters are singularly alive, interesting and likeable. The four dervishes, King Azad Bakht and Khaja Sag-parast stand out as individuals, and have the power to elicit the sympathy and interest of the reader. The incidents are of the usual kind, that is to say, far-fetched and with a mixture of the supernatural, yet the supernatural is not laid on with such a heavy hand as in Araish i Mahfil but sparingly.

The story is of men and their joys and sorrows and disappointments, the supernatural intervenes only now and then, while in Araish i Mahfil one gets the impression that the man has, by mistake, tumbled into a land peopled by monsters and dragons, and giants and fairies. The human interest in Bagh o Bahar never gets submerged under an overlay of the supernatural; most of the incidents of the story are not improbable, only a few are impossible.

The characters of Bagh o Bahar encounter strange and unusual adventures in a faraway land. They have no authenticity about them, but there is an air of plausibility in it all. In days when access to and penetration into other countries was so difficult, it was very likely that anyone who ventured forth would meet with strange rites customs, and so the experiences of the four dervishes, in their wanderings round the world, and the Khaja Sag-parast, take on the semblance of reality.

Araish i Mahfil, however, enjoyed a great deal of popularity in its earlier days. It is difficult to account for this, as it seems to be extremely cumbersome in style. There are roughly three adventures to a page, and the reader is thoroughly confused and only by repeated and vigilant reading can keep the thread of the story before his mind. It is extremely difficult, however, not to lose it among the innumerable and unconnected series of incidents.

The framework of the story is this. Husun Bano, the daughter of a merchant who had miraculously come into a great fortune, has declared that she will marry anyone who will answer her seven questions. A young man named Munir falls in love with her, but has not the courage to seek for the answers to the questions. Hatim, the prince of Tai, who is the most kind-hearted of men, takes pity on him and sets out to find the answers for him …

The story is spoiled by overloading of incidents. There are far too many of them, and it is utterly impossible to keep count of them or remember them even while reading. They come crowding in without sequence, and they do not lead to the ultimate solving of the riddles. Their solution only appears when Sher Ali Afsos feels like winding up the chapter, and then he just stops and thinks out the answer and gives it without any regard to the fact that nothing that has gone before has, in any way, contributed or led up to it.

In Bagh o Bahar, incidents are nicely dove-tailed into one another. There is a gradual sliding into one from the other. In Araish i Mahfil the chief defect is that it does not allow any impression to be formed, or any image, to be created in the mind. The framework of the story was ingenious, and had Afsos restricted himself to the inventing of incidents, he might have created a readable and enjoyable story.

Mazhab i Ishq or Gul Bakaoli is another of these well-known Gilchrist translations. The story existed in several versions already. There was the Masnavi Gulzar i Nasim as well as a Persian prose version of the same story. The translation, into Urdu was done by Nihal Chand Lahauri. It is in simple, unadorned prose. If it has succeeded in avoiding the then common fault of over-elaboration, it has failed to achieve the simple dignity of Bagh o Bahar. It has no style, so it cannot be called literature. It has the prosaic quality and flatness of a textbook, and that is what it was meant to be.

Literature cannot be produced to order, nor was Gilchrist aiming at doing so. He was out to get books that could be used in teaching English officers the language quickly. Nihal Chand Lahauri incorporates much less in his translation than Mir Amman and Sher Ali Afsos. His is a fairly accurate rendering of the well-known story of Taj ul Muluk and Bakaoli. There is no background or local colour in it, but as in Bagh o Bahar and later in Fasana i Ajaib, in it can also be seen the reflection of manners and customs of the India of that day. The description of Bakaoli’s marriage ceremony tallies in every detail with the customs of Indian marriage. The attitude of Bakaoli and Ruh Afza’s parents on discovering the misdemeanours of their daughters is that of Indian parents; but Gul Bakaoli at no point shows any literary merit.

The other translations done in Fort William are more or less collections of short stories, and not full-length romances. Of these Tota Kahani was very popular, and though really only a collection of short stories or fables, the fact of being encased in the framework of another story gives it a claim to be regarded among the longer romances. The stories are told by a parrot who uses these means to prevent the wife of his master from meeting her lover.

The way in which the parrot every day excites Khujista’s interest is psychologically most interesting. Casually, just by the way, not in the least appearing to detain her or being desirous of doing so, he mentions that he hopes that in her case it would not happen as it did in the case of so-and-so. Khujista’s curiosity is at once aroused and she stays on to hear what it was that had happened, and so day after day he prevents her from meeting her lover.

His tactics and mode of approach vary. He does not go on saying, as he did the first few days, that he hopes her affair would not end as so-and-so’s did, or that of course in love you never can tell, as it happened in the case of etc, etc; he varies his tactics as time passes. Sometimes he says, “You have been delaying, and if your lover is angry, show tact as did so-and-so,” and then follows the tale. Next time he warns her not to get caught, and tells her what to do if she does. On another occasion, he tells her to be as resourceful as so-and-so, and then commences another tale.

As the day of her husband’s return draws near, the parrot’s counsels take on a different tone. “Supposing your husband returns and finds out what you have been doing, this is how you should behave,” and that leads on to another story. In fact, how the Tota finds an opening for his stories is really clever, and does great credit to Haider Bakhsh’s inventiveness. The language is simple, straightforward and easy, there is no rhetoric or style about it.

Bahar i Danish is a similar collection of short stories inset in a longer tale. This encasing of shorter stories in the framework of a larger was very popular amongst earlier writers. Examples of it are found in every language: Alf Laila is itself written in this manner, and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales are also similarly put together.

Nasr i Benazir is the prose version of Mir Hasan’s Masnavi, Sihr ul Bayan and Shakuntala, a rendering in the form of a narrative of the story of Kali Das’s world-famous drama. These translations, however, are less known than Bagh o Bahar, Araish i Mahfil or Tota Kahani and did not have the same vogue.

All these translations, done under the auspices of the Fort William College, went towards the simplification of prose and the popularisation of prose romances.

Excerpted with permission from

A Critical Survey of the Development of the Urdu Novel and Short Story

By Shaista Akhtar Bano Suhrawardy (Begum Ikramullah)

Oxford University Press Plot # 38, Sector 15, Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi

Tel: 111-693-673

ouppak@theoffice.net

www.oup.com.pk

250pp. Rs495

Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah

Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah (1915-2000) was an active participant in the struggle for independence. In 1947, she was appointed to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan.

She was a member of the Pakistani delegation to the UN in 1948 where she served as a member of the Third Committee, which formulated the Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention against Genocide. Between 1964 and 1967, she was Pakistan’s Ambassador to Morocco. The Government of Pakistan awarded her the Nishan-i-Imtiaz in 2001. Her other books include Letters to Neena (1951), From Purdah to Parliament (1963 and 1998), Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy: A Biography (1991) and Behind the Veil (revised edition, 1997).

Urdu literature by Sultans of India

July 16, 2006

REVIEWS: Men of culture and war

Reviewed by Dr Asif Farrukhi

IN the days of yore, kings and princes were expected to be more than mere monarchs. They were themselves schooled in arts and culture so that they could play the role of patrons of fine arts and scholarship. The men who ruled the Delhi throne were no exception.

The Emperor Akbar was an unlettered man himself, but his glittering court drew poets, scholars and men of learning to him from far and wide, making it a great centre of learning. The Emperor Jahangir, not so astute a statesman as his worthy father, nevertheless continued patronage of the arts. The Mughal court soon became the great centre of classical Persian poetry.

In painting, the breathtaking illustrations of Dastaan-i-Ameer Hamza and other classics were produced. Not simply patrons, these emperors were accomplished in learning and scholarship themselves, not the least of their abilities being the skill of responding in verse at the spur of the moment. These feats are presented in the series of essays which make up the two volumes under review.

The late Sabah-ud-Din Abdur-Rehman, who has authored these essays, was a scholar and man of erudite learning, and knew how to make historical subjects interesting without being pedantic. He was associated with the Darul Musanifeen at Azam Garh, which became a great cultural institution at the hands of no less a person than Shibli Nomani. He worked hard to make the institution financially sustainable and kept alive its distinguished publication programme. A well-known scholar himself, he penned about two score books himself, mainly on historical themes. He was well-suited to taking up the pen and digressing on such as the learning and contributions of the men who sat on the throne of India.

The author left these articles in the dusty archives of periodicals, which have been dug out by the editor

Unfortunately he did not take up this task. Instead of writing a book, or series of books on the subject, he wrote a number of articles on various aspects. These articles were published in the journal Mu’arif throughout this long writing career. They have now been collected in two separate volumes, with a somewhat misleading title as “Sultan” is now generally used for the Muslim rulers of India before the Mughal emperors, in what is generally referred to the Sultanate period. The articles included here cover this period as well as the Mughal rulers.

The first book includes articles on the art of warfare, weapons and military administration as well as textiles, feats and holidays, while those in the second volume focus on the literary tastes of the Mughal rulers. A long article on the verse history written in the eighth century AH describing the military conquests of the different rulers, from Mahmood Ghaznavi to Mohammed Tughlaq, does not really fit in with the themes of the other articles. The articles collected here were written over long stretches of time, but most of them were written in the ’30s. As is inevitable with such articles, there are the usual repetitions, statements which may even seem contradictory and some points which need to be revised in the light of latter-day scholarship. The author left these articles in the dusty archives of periodicals, which have been dug out by the editor, but only partially.

However, the books seem to have been put together with little or no editing. A few footnotes have been provided, but there are no references. In a number of areas, the information is outdated. The “Adabi Khidmat” articles include a study of the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah, known as a poet with the takhalus of Zafar. He is generally regarded as an important Urdu poet in his own right and the author has pointed an accusing finger at Azad who implied that Zauq was the real author of his poetry. Azad was of course writing soon after the turmoil of 1857 and could not be impartial towards the deposed emperor.

Dr Aslam Pervaiz, the Indian scholar, has written in detail about Bahadur Shah’s life, while critics such as Shanul Haq Haqee and Khalil ur Rehman Azmi have explored the literary qualities of his poetry. The editor makes no reference to such well-known developments in the field of study and hence has not well served the scholar whose work is presented here. Surprising too is the fact that the articles on warfare have been put together with the odd pieces on festivities and textiles. The two items do not constitute tamaddun and even if they did, they make odd companions for the essays on warfare and military power. Culture has been made a bedfellow of the considerations of military rules of the game only for the sake of editorial convenience.

While it is interesting to read about the feats of kings and emperors, surely we now need to take a different view of this and understand that culture and history are the domains of the people, more than that of kings. When these essays were first written, they must have been of value in highlighting the cultural aspects of the ancient kings against the colonial context. The situation has changed over the years and we need a fresh perspective on our history.

Salateen-i-Hind ki Adabi Khidmaat

310pp. Rs225

Salateen-i-Hind: Funoon-i-Harb Aur Tamaddun 392pp. Rs250

By Syed Sabah-ud-Din Abdur-Rehman

Compiled by Dr Mahjabeen Zaidi

Manzil Academy, A-10, Al Karam Square,

Block 3, Liaquatabad, Karachi.

Tel: 0320-4002766

Urdu in the courts of law: real and Filmistani

Even as an Urdu festival in the capital brought the language into the limelight, Malini Nair looks at how it lives on in filmy courts, and real ones

`Milaard, gawahon ke bayanat seye saabit hota hai ki Mr Rajesh begunaah hain....Qaid-e-bamushaqat...Taazirat-e-Hind dafa teen sau do ke tehat...Mere kaabil dost...Muvakkil...“

Urdu legalese has thundered across filmy courts for as long as we can remember. The grimness of tazeerat-e-hind, as milard sent it flying across the courtroom like a hammer backed by the full weight of justice, was a formidable thing even if we didn't know that it meant the Indian Penal Code. Qaid-e ba-mushaqat led to chakki-pissing and stone breaking even if we couldn't break it down to rigorous imprisonment. Ba-izzat bari meant mulzim's mother and heroine sighed in relief and touched their sari to their wet eyes at acquittal. And Dafa 302 meant end of the road for the man in prison stripes.

Bollywood has courted Urdu for decades.In reality too, the legal system has used adaliya zubaan (the language of the courts) for nearly two centuries now. Minus the theatricality, of course.

`Urdu ka Adaalati Lehja', among the most entertaining and enlightening sessions at the recent Jashn-e-Rekhta festival, discussed the many ways the elegant language livens up the grim proceedings of Indian courts. The festival is an annual celebration of Urdu in Indian life and literature.

“Persian was the language of the Mughal court, and Urdu replaced it in the late 19th century . The Adalat System, set up in 1772 by Warren Hastings was a mix of both British and Mughal Courts. In this system, Urdu came to be the language of the lower munsif 's courts,“ says Saif Mahmood, a Supreme Court advocate and an expert on Urdu poetry and literature, who conducted the session.The legal Urdu we know today is largely the gift of novelist (Dipty) Nazeer Ahmed who translated the Indian Penal Code in 1860.

Interestingly , the most lyrical insight into the judicial system of mid-to-late 19th century India, and Urdu's place in it, comes from the incomparable Ghalib, a man Mahmood describes as “a litigious commoner“. “Ghalib spent 20 years of his life litigating in every court of the existing judicial system on issues ranging from pension and debt recovery to gambling. His life as a litigant hugely influenced his poetry,“ says Mahmood. One of Ghalib's best-loved five-verse set (qata) quoted in Mahmood's research paper starts thus: Phir khula hai dar-e-adaalat-e-naazGarm bazare-faujdari hai (The door of the court of co quetry is open againThere is a bazaar-like briskness about the criminal case).

The distinguished legal scholar and jurist Tahir Mahmood, a panelist at the talk, has written on `Legal Metaphor in Ghalib's Urdu Poetry'. And among the couplets he lists is the much-loved “Dil mudda'i o deeda bana mudda'a alaihNazaare ka muqaddama phir roobakaar hai (Heart is the Plaintiff and eye, the defendantThe case of gazing is being heard again).“

Today, words such as vakalatnama (a document authorizing a lawyer to act on behalf a client) and sarishtedaar (court officer) are used even in courts where Urdu is not otherwise used, like Bombay High Court and Supreme Court. Until the 1970s, Urdu continued to be used in the district and sessions courts of north India, especially UP, Punjab, Bihar and Jammu and Kashmir, in the filing of pleadings.

The FIRs and the police roz namcha (daily journal), which can be called into evidence in court, often throws up delightful usage of archaic Urdu. “Khadim PP sahib ko namaz-e-eid-ul-fitr ada karane 10.30am le gaya Ba-qalam khud“ thus ran a florid entry in a recent roz namcha of a VIP security officer that Mehmood stumbled upon.Simply put: I, the undersigned, escorted my protectee to the namaz today at 10.30am.

Urdu also works as a happy means of intellectual jousting between lawyers and judges.And a superb example came from the recently retired Chief Justice of India TS Thakur, known for his love of Urdu. As a judge of the Delhi High Court, he was once hearing a case for the Delhi Government being pleaded by Najmi Waziri, now a sitting judge of the same court. The case was adjourned for five or six months and the lawyer sought a shorter date.Justice Thakur denied the plea. At 1.15pm as the court broke for lunch and the judge rose from the bench, the lawyer remarked despondently to no one in particular: Kaun jeeta hai teri zulf ke sar hone tak (who is going to live till you deign to decide)? Justice Thakur paused as he stood and said: Pehla misra padho (read the first line). And the lawyer obliged with the opening lines of Ghalib's famous couplet: Aah ko chahiye ek umr asar hone tak (it takes a lifetime for a prayer to find a response). Justice Thakur famously listed the case for the following week.

Justice Syed Mahmood in the late 1890s famously quoted Urdu poetry in his landmark judgements. And even today, Sahir and Faiz lend a human touch to the grimmest of verdicts.

But does Urdu shayari affect the gravitas of rulings? Justice Aftab Alam believes in minimal usage. He recalled using a verse to describe the naïve but effective defence of a petitioner in Patna High Court. “But why did you use it? Did it enhance your judgement?“ he was asked later by a mentor.“I have since stopped using any shayari in my judgements,“ he joked.

Justice Thakur used a hilarious couplet to explain how Urdu works to cut the verbal clutter in courts: “Kucha-e-yaar mein agar bheed bhaad hoTum bhi koi sher ghusad ghasad do (if your lover's lane is full of rivals, then you too shove in some poetry).“

Vocabulary

Bastard: walad uz zina bit tehqeeq