United Nations and India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Election to UN agencies, commissions etc

Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions

2020: Indian elected

November 8, 2020: The Times of India

Indian on panel that holds UN purse strings

NEW DELHI: In what is seen as a significant achievement, Indian diplomat Vidisha Maitra has been elected to a key United Nations committee that controls the financial and budgetary purse of the world body.

Official sources said the government sees the development as important as it comes just when India is preparing to take over as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council for the next two years.

Maitra was India’s candidate for the only post in the Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions (ACABQ) from the Asia Pacific Group. The other candidate was from Iraq.

India has been a member of the committee since its inception in 1946. The committee is one of the most coveted in the UN system as it controls its financial and budgetary purse.

“ACABQ performs several functions including the examination of the budget submitted by the UN secretary-general to the General Assembly and advising the Assembly on administrative and budgetary matters referred to it. ACABQ is a crucial component in ensuring that resources of the member-states are used to good effect and that mandates are properly funded,” said a source.

Members are elected by the General Assembly, consisting of 193 member-states, on the basis of broad geographical representation, personal qualifications and experience and serve for a period of three calendar years. Members serve in a personal capacity and not as representatives of member-states, added the source.

Maitra is a career diplomat with the Indian Foreign Service and currently posted as first secretary in permanent mission of India to UN in New York. She has served in various capacities in New Delhi, Paris, Port Louis and New York over the last 11 years. “She has extensive work experience in strategic policy planning and research, formulation and implementation of development assistance and infrastructure projects, defence acquisition matters, international taxation issues, investment and trade promotion,” said a source.

Vidisha Maitra’s selection in this committee is seen as crucial as the country will also be in the UNSC as non-permanent member for the next two years.

UN Commission on the Status of Women

2020: India defeats China

India defeats China in UN poll, September 16, 2020: The Times of India

In a significant victory, India got elected as member of the UN Commission on the Status of Women, the principal global body focussed on gender equality and women empowerment, beating China in a hotly-contested election. While India got 38 votes of the 54 cast, China managed 27.

Envoys

Technology

June 12, 2022: The Times of India

United Nations: Senior Indian diplomat Amandeep Singh Gill was on Friday appointed by United Nations secretarygeneral Antonio Guterres as his envoy on technology, with the UN describing him as a “thought leader on digital technology” who has a solid understanding of how to leverage the digital transformation responsibly and inclusively for progress on the Sustainable Development Goals.

Gill, who was India’s ambassador and permanent representative to the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva from 2016-to 2018, is the chief executive officer of the International Digital Health and Artificial Intelligence Research Collaborative project, based in Geneva.

Previously, Gill was the executive director and co-lead of the UN secretary-general’s high-level panel on digital cooperation (2018-2019). PTI

Indians in the United Nations bureaucracy

2018: Atul Khare, Nikhil Seth, Satya S. Tripathi

UNITED NATIONS: Development and environment expert Satya S. Tripathi has been appointed an assistant Secretary-General and will head the UN Environment Programme's New York office.

The appointment made by Secretary-General Antonio Guterres was announced by his Spokesperson Stephane Guterres.

Tripathi is now the third Indian at the senior levels of the UN hierarchy.

He has served the UN for 20 years in "Europe, Asia and Africa on strategic assignments in sustainable development, human rights, democratic governance and legal affairs," Dujarric said.

Tripathi has been the Senior Adviser on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at the UNEP since 2017.

A development economist and lawyer with over 35 years of experience, one of his key roles at the UN was as the UN Recovery Coordinator for the $7 billion post-tsunami and post-conflict recovery efforts in Aceh and Nias in Indonesia.

He also chaired the Committees on Laws and Treaties for the UN-mediated Cyprus unification talks in 2004.

Tripathi has commerce and law bachelors degrees and a masters in law from Behrampur University in Odisha.

Atul Khare, the Under-Secretary-General who heads the Department of Operational Services, is the senior-most Indian at the UN.

Nikhil Seth, the Executive Director of UN Institute for Training and Research, is at the level of an assistant Secretary-General according to last year's Voluntary Public Disclosure listing of senior staff's assets.

At the New York office of UNEP, Tripathi's duties will include supporting development, coordination and implementation of system-wide strategies on environment for the UN and "catalysing transformative change" throughout the UN "to integrate the environmental dimension of peace, security and sustainable development," according to the description of the post.

Security Council

Permanent membership and Nehru

DP Srivastava, May 15, 2019: The Times of India

Over past few years, a number of articles have appeared on the offer of permanent membership of UN Security Council to India in the 1950s. I discovered, as director in the Ministry of External Affairs, the original file on the subject in 1995, which included internal deliberations of the period. It was put up to me for orders for destruction, as part of a routine exercise of ‘weeding out’ old files.

Realising its importance, i brought it to the attention of my seniors. I also wrote a letter to our UN mission in New York. My letter was later circulated to our missions in P-5 capitals. In response, our Moscow mission forwarded more information on the subject. I had suggested that the file be declassified and transferred to the National Archives as it had no operational significance.

Without going into details of the file at this stage, we can revisit the issue on the basis of considerable material declassified since then. This includes records of Nehru’s exchanges with Soviet leaders in 1955, and Vijayalakshmi Pandit’s correspondence with her brother earlier during her tenure as Indian ambassador to the US. The file on the question referred to the Soviet offer of the mid-50s. Papers on the earlier offer are available in the Vijayalakshmi Pandit collection in the Nehru Memorial Library. Anton Harder of the Woodrow Wilson Center has published a research paper on the subject.

While the Soviet offer was for India to be inducted as sixth permanent member, the earlier US offer was for India to replace China in the Security Council. Nehru and Krishna Menon suspected the American offer as a Western ploy to set India against China, and therefore were opposed to it. The Soviet offer of India joining as a sixth permanent member did not pose any such dilemma.

Nehru’s Selected Works contain a record of Nehru’s discussions with Russian Prime Minister Nikolai Bulganin on the subject: Bulganin: “While we are discussing the general international situation and reducing tension, we propose suggesting at a later stage India’s inclusion as the sixth member of the Security Council ...”

Nehru: “Perhaps Bulganin knows that some people in USA have suggested that India should replace China in the Security Council. This is to create trouble between us and China. We are, of course, wholly opposed to it …”

Bulganin: “We proposed the question of India’s membership of the Security Council to get your views, but agree that this is not the time for it and it will have to wait for the right moment later on …”

Pandit Nehru did not respond to Bulganin’s suggestion to include India as a sixth permanent member; his reply was in the context of an earlier American proposal for India to replace China. Bulganin could not have been part of any Western ploy. Induction as sixth member would have finessed the issue of Chinese representation. Bulganin agreed not to push the matter after Nehru unequivocally rejected Bulganin’s offer. This cannot be interpreted to suggest the Soviet offer was not serious. We cannot expect our friends to push our cause if we did not see their offer was in our interest.

To put a bilateral understanding into effect a Charter amendment was needed. The Charter envisaged a General Conference before the tenth annual session of the General Assembly, or the proposal to be placed on the agenda of the session of the UN General Assembly. This deadline was fast approaching in 1956. In a parallel move, the Latin American group had inscribed an item on the agenda of 11th UN General Assembly in 1956. Though this was for expansion of non-permanent members category, the scope could have been widened to cover expansion of permanent members category, or a separate agenda item inscribed on the subject. Even if no immediate decision was reached, this would have kept Indian candidature alive for a later date.

The US proposal for permanent membership for India pre-dates the Soviet proposal. Vijayalakshmi Pandit, as India’s US ambassador, reported to Nehru in August 1950 about a move in the State Department to replace China with India as a permanent member in the Security Council. She said, “Dulles seemed particularly anxious that a move in this direction should be started.” She described the episode in derisive terms as being “cooked up in the State Department”, and advised her American interlocutors “to go slow in the matter as it would not be received with any warmth in India”. Nehru agreed with his sister’s view in his reply, as otherwise it would mean “some kind of break between us and China”.

Nehru’s anxiety not to disturb India’s relations with China did not prevent deterioration of relations in the next decade. This was not the result of American machinations, but Chinese aggression.

UN processes take time. No decision could be reached in 11th UN General Assembly session. The Charter amendment to expand the Security Council from 11 to 15 took place only in 1965. The Indian political leadership refused to pursue Indian candidature at the outset. It would take more than two decades to revive discussions on expansion of the Security Council in the 1990s. These are still inconclusive. Any future Charter amendment for India’s inclusion would be subject to Chinese veto. The Masood Azhar case underlines the difficulty.

The People’s Republic of China replaced Taiwan in the UN in 1971. They exercised their first veto over admission of Bangladesh to the UN in August 1972 to neutralise India’s geo-political gains during the 1971 war. The file on the offer of permanent membership should be traced and declassified. The nation has a right to know.

The writer, a former diplomat, has headed the MEA’s UN desk

What the UN Security Council is and why PM Modi chaired a 2021 session

Sushmita Choudhury, August 11, 2021: The Times of India

From: 5.2==What the UN Security Council is and why PM Modi chaired a 2021 session== Sushmita Choudhury, August 11, 2021: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury, August 11, 2021: The Times of India

On August 9, Prime Minister Narendra Modi chaired a United Nations Security Council (UNSC) high-level open debate on enhancing maritime security through video conferencing. According to the government, although the 15-member UNSC has discussed and passed resolutions on different aspects of maritime security and maritime crime, this was the first time that maritime security was discussed in a holistic manner as an exclusive agenda item in a high-level open debate.

The meeting was attended by several heads of state, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, along with a long list of foreign ministers and high-level briefers from the UN system as well as key regional organisations. India has long nurtured hopes of entering the ranks of the permanent members of the Council — comprising the US, the UK, Russia, France and China — and the impressive attendee list is being seen as a sort of validation for that bid. This, incidentally, is the first time that an Indian Prime Minister is chairing sessions of the UNSC. "It shows that leadership wants to lead from the front. It also shows that India and its political leadership are invested in our foreign-policy ventures," Syed Akbaruddin, former permanent representative of India to the UN, told ANI.

India assumed the rotating presidency of the UNSC in the beginning of August and will be hosting signature events throughout the month. The country was elected as a non-permanent member last June and the two-year tenure began on January 1.

In December, ahead of the term’s commencement, India's Permanent Representative to the UN TS Tirumurti said that the country’s priorities would be counter-terrorism, peacekeeping, maritime security, reformed multilateralism, technology, women, youth and developmental issues, especially in the context of peace-building.

Here’s a detailed look at the workings of the UNSC, how it votes for the non-permanent members, how the presidency is determined and more.

What is the UNSC?

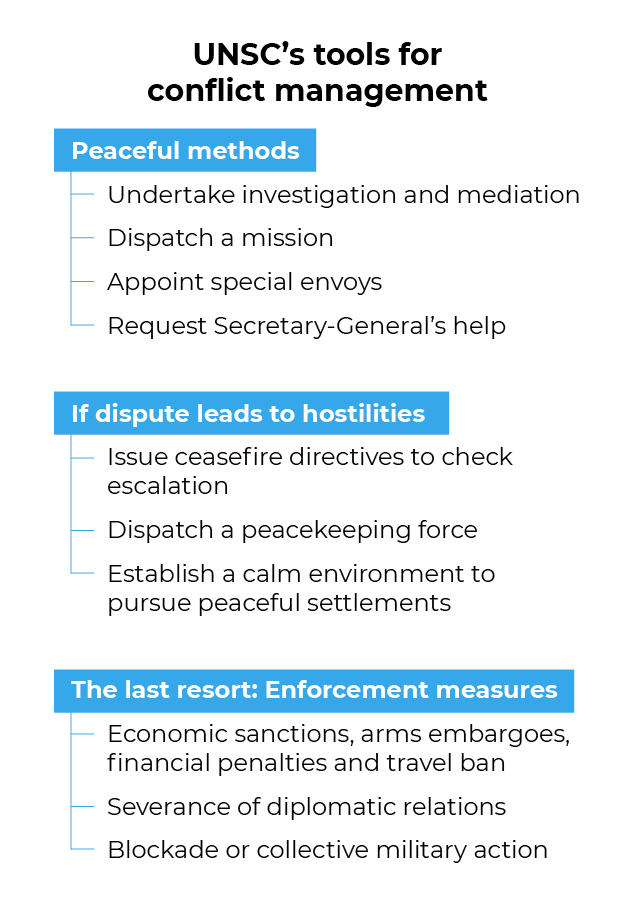

The Council, one of the six main organs of the UN, came into being in 1945 when the United Nations Charter was signed. This body has been charged with maintaining international peace and security. The UNSC’s five permanent and 10 elected members meet regularly to assess threats to international security, addressing issues that include civil wars, natural disasters, arms control and terrorism. Significantly, its resolutions are binding on all the 193 member countries of the UN.

Though it has achieved a lot over the past 76 years — be it setting up over 70 peacekeeping operations, establishing two international criminal tribunals or unleashing sanctions — in recent times it faces increasing calls for reform to better meet the geo-political realities of the 21st century.

“In recent years, members’ competing interests have often stymied the council’s ability to respond to major conflicts and crises, such as Syria’s civil war, Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the coronavirus pandemic,” notes New York-headquartered think tank Council on Foreign Relations (CFR).

How are the 10 non-permanent members elected?

The 10 non-permanent members are elected by the General Assembly for a two-year, non-renewable term. In 1963, when the number of elected members was increased to 10, a system of equitable geographical distribution was established as a criterion for selection. These seats were henceforth elected on a staggered basis as follows:

Two seats for the African group in odd years, with one seat available during even years

Two seats for the Western European and Others groups in even years

One seat for the Asia Pacific Group in odd years

One seat for the Latin American and Caribbean group every year

One seat for the Eastern European group in odd years

One “Arab swing seat” that alternates between the African and Asia Pacific groups in odd years

However, the main criterion for eligibility is still a member state’s contribution towards the mandate of the UNSC, typically defined by financial or troop contributions to peacekeeping operations or leadership on matters of regional security.

To get elected as a non-permanent member of the Council, a country need to secure votes from two-thirds of the member states present to cast ballots

What’s the election process?

The UN member states keen to seek a Security Council seat have to first inform the rotating monthly chair of their respective UN regional groups, specifying the two-year period they wish to vie for. “The chair incorporates this information in the UN candidacy chart, which is maintained by each regional group, and reviewed at monthly group meetings,” reads the UN Security Council Handbook prepared by the Security Council Report.

The candidates to the Security Council then seek vote commitments from the other member states, a process that can start years ahead of the actual Election Day. The contributions of the candidates to the purposes of the UNSC as well as towards maintenance of international peace are important factors that come into play at this stage.

To secure its seat, a country must obtain votes from two-thirds of the member states present and voting at the General Assembly meeting, regardless of whether the election is contested. This means that a candidate has to bag at least 129 votes to win a seat if all 193 member states participate in the election.

According to the UN, since 2010, 78% of races for Security Council seats have been uncontested. However, formal balloting is required even if candidates have been endorsed by their regional group and are running unopposed.

How many times has India become an elected member in the past?

This is India’s eighth stint in the Council. In June 2020, as the endorsed candidate from the Asia-Pacific group, India won 184 votes out of the 192 ballots cast. Some posts on social media at the time had claimed that this was the highest number of votes ever garnered by India in UNSC elections.

However, that is not true. In October 2010, the last time India got a seat on the table for a tenure starting in January 2011, it had received 187 votes, the highest among the candidates. Before that, India had been elected for the years 1950-1951, 1967-1968, 1972-1973, 1977-1978, 1984-1985 and 1991-1992. The country also held presidency multiple times during these stints.

How is the UNSC presidency decided?

The presidency of the Council is held by each of the member states for one month in turn following the English alphabetical order of their names. Before India, France held the UNSC presidency and in September 2021, the baton will be passed to Ireland. India will again preside over the Council in December 2022, the last month of its two-year tenure at the horseshoe-shaped table.

Who chaired past UNSC sessions during India’s presidency?

The last time an Indian prime minister participated in a UNSC session was PV Narasimha Rao in 1992. No Indian prime minister before Modi chaired a session. India sends senior diplomats to preside over meetings during its presidency. For instance, Samar Sen, the then Indian ambassador to the US, was the president of the Security Council during December 1972 while former Indian ambassador to the UN Chinmaya Gharekhan bagged the role twice — in October 1991 and December 1992.

Most recently, Union minister Hardeep S Puri, who twice served as Permanent Representative of India to the UN, presided over the UNSC in August 2011 and November 2012.

Have other heads of state previously chaired UNSC sessions?

Yes. For instance, in February 2021, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson chaired a session on climate and security. During this period, the UK had held the presidency of the UNSC. This, incidentally, was the first time a British PM chaired the UNSC since 1992.

The US President has chaired UNSC sessions three times — most recently in September 2018 when former president Donald Trump presided over a meeting on Iran. Presidents and heads of government of smaller countries such as Vietnam, Bulgaria, Lebanon, Poland and Kazakhstan have also presided over sessions in the past.

What are the powers of the Council president?

According to the UNSC handbook, the president calls meetings when necessary and presides over them, approves the provisional agenda and signs the verbatim record of council meetings. Should the Council be deliberating on an issue that has a direct connection to the country holding the presidency, the latter is expected to cede the role.

The president also has the power to accord precedence to any rapporteur appointed by the council during a meeting and state a ruling if a representative raises a point of order. The nation holding the presidency has to refer all applications for UN membership to the relevant committee for such matters.

How are decisions taken at the UNSC?

Each member state gets one vote. When it comes to procedural matters, Council decisions require affirmative votes of nine members, with no distinction between the votes of permanent members and the other members. Since 2018, the UNSC has held 10 procedural votes, on issues such as North Korea, Myanmar, Syria and Ukraine.

However, when it comes to substantive matters, it is the permanent members that hold a politically significant institutional advantage. For such matters, while a decision of the Council still needs nine affirmative votes, a negative vote from one of the permanent members is regarded as a veto. The abstention, non-participation or absence of a permanent member is treated as a concurring vote.

In the post-Cold War era, France and the UK have not cast a veto even once — their last veto was in December 1989 when they went together with the US to block the condemnation of the US invasion of Panama — but China is increasingly exercising this option. It cast 15 of its 16 total vetoes between 1997 and August 2020, most of them in tandem with Russia in recent years. Incidentally, Russia had cast the highest number of vetoes till August 2020 — 117 — followed by the USA at 82.

What’s holding back India from becoming a permanent member?

The short answer is China, one of the five permanent members holding veto power. Although the other four members, the US, the UK, France and Russia, have expressed backing for New Delhi's membership in recent times, China has been consistently stonewalling India's efforts.

The Trump administration as well as former President Barack Obama had publicly said that the US supports India's bid to be a permanent member. US President Biden had reiterated this promise in his campaign policy document last year.

In January 2020, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov categorically stated at the Raisina Dialogue that “India should absolutely be at the United Nations Security Council. Developing countries should be given adequate representation there”. Eight months later, French Defence Minister Florence Parly too reiterated her country's support to India’s bid.

Of course, we are not the only country vying for a permanent seat. The “Group of Four” (G-4) comprising Brazil, Germany and Japan in addition to India, have similar aspirations. But the Uniting for Consensus group of 12 countries, also referred to as the Coffee Club, vehemently opposes any expansion in the number of permanent members. Led by Italy, Argentina, Pakistan and Mexico, this club instead proposes expanding UNSC non-permanent membership to 20 members.

“The implementation of the Council’s decisions, and its very legitimacy, could be enhanced if the Council was reformed to be more representative, effective, efficient, accountable and transparent,” UN General Assembly President Volkan Bozkir noted in an informal meeting of the policymaking organ in January. But then again, given that the reforms have been tabled and discussed for several years with no traction yet, nothing is likely to change in the foreseeable future.

Sources: UN, Council on Foreign Relations, ANI, PTI, Ministry of External Affairs

Maritime security

Indrani Bagchi, August 12, 2021: The Times of India

At least two previous attempts to address the issue of maritime security in the UN Security Council went nowhere. Vietnam had tried to push it in April 2021 and Equatorial Guinea in February 2019, without success.

In the lexicon of current global politics, “maritime security” is code for Chinese actions in the South China Sea. Being extraordinarily sensitive to this, China has nixed previous attempts.

India was determined to make an impression in its month at the helm of the UNSC, and used its considerable diplomatic heft to put together the first standalone session on maritime security, which went beyond piracy and crime. The final presidential statement which was adopted set out a framework of existing international laws to govern activities at sea — from UNCLOS to the SUA Convention and a host of others in between. By reaffirming these laws, the message was that enforcing a rules-based order was something countries would push.

The final presidential statement didn’t try to over-reach sticking to subjects that would be acceptable to all members. Indian negotiators were at work on document for the past couple of months, trying to get everyone on board. Territorial sovereignty issues don’t find mention, neither does illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, both of which were objected to by China. Chinese fishing militia has been linked to overfishing in seas as far away as South America, while China’s aggressive island building and bullying in South China Sea has made all of south-east Asia nervous.

However, since almost all the speakers dwelt at length on the issue of territorial sovereignty and the importance of UNCLOS, it wouldn’t have pleased the Chinese. That was also why Beijing was represented by deputy permanenet representative Dai Bing, as a deliberate snub to India and the proceedings. The outcome document re-established the primacy of international law – UNCLOS, as the legal framework applicable to activities in the oceans, including countering illicit activities at sea.

The outcome document also focused on strengthening cooperation for maritime safety and security, including against piracy and armed robbery at sea and terrorist activities, as well as against all forms of transnational organised crimes and other illicit activities. The other deliverables include stressing freedom of navigation and protection of cross-border infrastructure. PM Narendra Modi personally wrote to all the heads of government to attend the session, which is established courtesy. Of the P-5, Putin was the only attendee at that level, which the Indian side appreciated as a significant gesture.