Uniform Civil Code: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

The debate

1930s to 2015

The Times of India, Nov 02 2015

Amulya Gopalakrishnan Why a common civil code may not be a great idea

Even if Parliament does design the dream civil code, it might be wiser to make it optional. That would encourage faster reforms in personal law, perhaps even prompt its gradual withering away The Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is a dream long deferred, and now it looks like the courts can barely conceal their impa tience. A Supreme Court bench, hearing a case on a Hindu woman's petition on inheritance, was recently stirred into ordering an examination of practices like polygamy and triple talaq in Muslim personal law, which it declared “injurious to public morals“. The Centre is already on a deadline from another SC bench to present its views on the UCC. Though the BJP once claimed the UCC as a burning priority , the government has been guarded in its response so far, calling for “consensus among all stakeholders“.

First raised by the All India Women's Conference in the 1930s, the UCC was once a simple demand for equal rights in marriage, divorce, adoption and succession for all women irrespective of religious laws. But since India was born in inter-religious strife, and was a pact between religious groups of unequal clout, the Constituent Assembly left this plan to the future.

At this point, who is Team UCC? The Hindu right-wing, which is aggrieved that minority cultures remain unscathed, even though Hindu practices were painfully codified in the 1950s.Liberals also believe that secular citizenship means strict equality before law, that the state and religion should be walled off from each other, and that India's regime of distinct personal laws, which discriminate against women in various ways, should be replaced by a fair civil code.

Those who resist the UCC include many believers, and also those who say that secularism is not a one-size-fits-all model, and that instead of uniform laws, the state should push for uniform principles of gender justice and individual freedom. It could root out gender-bias from various personal laws, as the courts and legislatures to a lesser extent have indeed been doing, rather than boiling everyone down to a common citizenship, they say .

Then there are those who do want a common civil code in the future, one that reflects the state's vision rather than majoritarian norms, but not in a situation where minorities feel anxious and alienated.

What Muslim women want

Many who argue for a UCC speak in tones of concern for Muslim women. Yet, among them, there has been no audible voice asking for it.

Most Muslim women's groups oppose polygamy and triple talaq, but do not want religious laws to be steamrollered. “If you follow Quranic injunctions correctly , women have more rights than men,“ says Shaista Amber of the All India Women's Personal Law Board, suggesting that courts should consult female muftis rather than self-appointed spokesmen of the community like the All India Muslim Law Board. “Islam is our religion, our conviction, we want to live and die within it.“

For Noorjehan Safia Naz of the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan, the problem is that “Muslim personal law is not codified, and therefore open to all kinds of contentions“.Apart from the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act of 1937, the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act (1939) and the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights of Divorce) Act and Rules (1986), judges have to rely on scholars of Islamic jurisprudence in a case-by-case manner. Naz advocates a comprehensive personal law code that removes triple talaq, polygamy and other unfair practices, and has drafted exactly such a model.

But not all Muslim women's groups are averse to the idea of a common code. “We want a gender-just set of family laws that is formed after listening to what women's groups want,“ says Yasmeen Aga of the Mumbai-based Awaaze-Niswan. But in parallel, “if a woman wants to follow the personal law of her religion, that choice should also be available,“ she adds.

Towards gender parity

“The general attitude is that Hindu law is reformed, Muslim law is anti-women,“ says lawyer Flavia Agnes. “But in terms of economic rights, the Muslim marriage-as-contract works out better for women, in terms of dower and traditional maintenance. Even with polygamy , the multiple wives have legal and social rights.“

She points out that the Hindu woman in a nonmarital domestic partnership is utterly without recourse -in 2010 the Supreme Court ruled that maintenance under the Domestic Violence Act did not cover such cohabiting couples, even referring to them as “concubines“.Legislation has made Hindu and Christian laws more receptive to women's rights -Hindu succession was reformed considerably in 2005, making all daughters coparceners in joint family property and giving them equal claims to agricultural land; in 2001, Christian women and men were brought on par, in terms of divorce rights.

“Meanwhile, the courts have done a creditable job in affirming the rights of Muslim women,“ says political scientist Narendra Subramanian, whose book Nation and Family: Personal Law, Cultural Pluralism and Gendered Citizenship covers this ground.

Subramanian details this remarkable reform process, showing how the courts have harnessed Islamic traditions and constitutional principles to expand individual rights.Even the ambiguously-worded Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act of 1986 that followed Shah Bano ruling has had a happier arc than commonly assumed, as courts have used it to award generous alimony payments to divorcees, and established, through the 2001 Danial Latifi ruling, that Muslim men owed their ex-wives ongoing maintenance. Apart from bending various personal laws towards justice, women's groups have focused on creating criminal and civil laws that apply to everyone, obviating the UCC -for instance, the Juvenile Justice Act now makes adoption equally available, the Domestic Violence Act and its protections apply to all citizens. The Special Marriage Act has been a way of opting out of personal law. “Why does there have to be a uniform code for gender justice?“ asks political scientist and feminist scholar Nivedita Menon. She argues that codification of Hindu law, in the image of north Indian upper castes, actually hurt certain women by ending matriliny and other practices that women gained from.Similarly, practices like mehr are unique to Muslim women, and they actually stand to lose from a civil code that doesn't accommodate it. Which is why, she says, much of the women's movement has abandoned the demand for a flattening UCC, likely to be shaped by dominant norms. Instead of standardisation, they press for principles like gender justice and individual autonomy within diverse personal laws.

How to be secular

The debate over UCC, then, is an argument about secularism. Contrasted with US-style “assimilative secularism“, India has its own kind of “ameliorative secularism“ that moulds the majority religion towards social equality , but gives minorities greater space. It may be infuriating to some and not good enough for others, but it does have an appreciation of minority group rights and multiculturalism, in ways that western liberal democracies have been lately contending with.

But there is a common view, recently voiced by historian Romila Thapar, that India must gradually remove any religious considerations from the law, to be strictly secular. “This would not be a cosmetic change; or mean uniformity only in personal law, but all the codes we conform to that are determined by religion or caste“, she says. That kind of strict uniform secularisation would upset many vote banks, apart from Muslims -it would end the Hindu undivided family's tax benefits, it would extend reservations to eligible castes in all religions.Assume that Parliament irons out all the conflicts and designs a dream civil code -through what Subramanian calls an “amplification of the Special Marriage Act“ -extending across all domains of family law. (Many women's groups have indeed floated versions of such a code). Should this be obligatory or optional? “If it is made obligatory in an environment where there is no social support for it or state capacity to implement, then you may be pushing women into sharia courts or other dispute resolution forums, as happened in Turkey . Look at the way khap panchayats reject the state's authority even in criminal and civil law,“ Subramanian says. If it is optional, it would give citizens a common set of rights, and also let them choose the sphere of personal law if they prefer. This might prompt further reform of personal law, to keep women within the fold.And conversely , for those who hope for secularisation in the Western mode, this would make the advantages of civil law obvious enough that personal law could slowly wither away .

1947, February-March: debates in favour of UCC

With communal conflict raging outside, the Constituent Assembly had to take a call on individual rights, the place of religion, and minority insecurity

Barely 24 hours after Jawaharlal Nehru's `tryst with destiny' speech, Claude Auchinleck, designated as supreme commander of the Indian and Pakistani armies, infor med Lord or `Dickie' Mountbatten, earlier viceroy and now governor-general, that India was in a state of civil war.

The situation in the subcontinent had turned combustible ever since the Muslim League had passed its 1940 `Pakistan' resolution, and Mohammed Ali Jinnah had raised communal tempers so much by 1946 that violence had broken out in many parts. With Partition and Independence had come mass migration and terrible slaughter. Hardly the perfect setting for India's Constituent Assembly , first convened in December 1946, to calmly focus on its job of framing a new Constitution.

Its members even had difficulty reaching the Assembly chamber for its fifth session in August 1947; with the bloodbath raging in both Old and New Delhi, they needed special curfew passes.

Yet this Constitutionmaking body, dominated by Congress, with nonCongressmen like B R Ambedkar the exceptions, was keen to transform India's political revolution into a social one and to create a document enabling social (and as part of it, economic) progress and fostering national unity and stability. It rejected at the outset the idea of a `Gandhian Constitution' (based on the village as a key unit of national life) and decided to accept the parliamentary government model adopted by leading Western nations.Fundamental rights and Directive Principles of State Policy (the latter inspired by the Irish Constitution) were to be the soul of this Constitution. But if the balancing of individual rights and the common good or `group interests' was a ticklish issue in a largely tradition-bound, caste-ridden and now communally-split society, there was an even more delicate matter to deal with the status of religion. The Assembly was clear that India would have no state religion -it would be secular. But whether secularism in the Indian context meant `total separation of church and state' as in some Western societies or `equal respect for all religions' was to be decided. Those in favour of `equal respect' won, as India was deeply religious, and the Fundamental Rights SubCommittee, one of the Assembly's key panels, put in a clause on the freedom to practise religion.

One of its members, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, however objected to this, saying `free practice' could legiti mise `anti-social practices' such as Sati, purdah and devdasi customs and nullify laws such as the one favouring widow-remarriage (the Constitution eventually adopted a provision saying the right to practice religion should not prevent the state from enacting social reform laws). The battle related to faith had begun soon after the Assembly was formed, and it became fierce when, during the discussion on citizenship, the matter of a uniform civil code was first raised. This was in February-March 1947, that is, in fact, some months before freedom came and months after communal violence had begun.

The rights sub-committee had 12 members. When it first met in February, it had in front of it drafts on rights prepared by some of its members like Ambedkar, K M Munshi, K T Shah and Sardar Harnam Singh, and also by the constitutional adviser B N Rau and the Congress Experts Committee, a party panel that had prepared a draft for the Assembly's `guidance'. The drafts of at least two members Ambedkar and Munshi included a clause on a common civil code as a justiciable right, meaning it would be enforceable by courts. Till the early 19 th century, religion had pretty much ruled the life of Indians. Following demands from Hindu social reformers, though, the British had gradually outlawed certain practices and, in 1946, readied a draft for reform of Hindu laws. Yet the majority of faith-based practices were left untouched, and in the case of Muslim personal law, the colonial power, always eager to divide and rule, had not intervened at all.

There were two opinions on this sensitive subject among Indian leaders at the time. One was that personal laws had to go at once in order to create a casteless, classless and united society on the basis of equality, direct elections and universal suffrage. The other was the view of Nehru and some other Congress leaders and, therefore, highly influential. Nehru and these netas felt the Muslims, who were facing the brunt of communal violence in many Hindumajority areas, had genuine fears, and the Constitution would have to allay these and provide the minority community a sense of security.This meant not touching their personal laws or the laws of the Sikhs, who were also affected by violence in the Punjab (claimed during Partition talks by both India and Pakistan; eventually it was divided).

As the Congress wanted to project itself as a secular outfit representative of all Indians, Jinnah's allegations from 1939 onwards that Congress governments in the provinces had “interfered with their (Muslims') religious and social life, and trampled upon their economic and political rights,“ established “a Hindu Raj“ and “emboldened Hindus to ill-treat Muslims“ must have worked on the minds of Nehru and other leaders too. So must have the Communist Party of India's 1943 resolution accepting “the essence of the demand for Pakistan“ which praised Jinnah and sought to paint Congress as a party with a religious bias. Here was a non-Muslim and an avowedly antithetical-toreligion p a r t y t o o b a ck i n g t h e League and its religionbased demand and branding Congress that had led the freedom movement.

Would the personal laws then stay or go, and did a unifor m code stand any chance? The rights subcommittee debates would determine that, followed by the decision of the Assembly's advisory c o m m i t t e e, h e a d e d by Sardar Patel, and then a consideration of the entire Draft Constitution by the Assembly .

1947, March: Uniform code as a justiciable right

The second of a four-part series on Constituent Assembly debates on the Code

Though they were all lawyers, Bhimrao Ambedkar, Kanhai yalal Munshi and Minoo Masani did not quite share an ideology. Ambedkar was an iconoclast committed to the uplift of Dalits, Munshi a conservative and believer in India's cultural renaissance, and Masani a democratic socialist who later embraced the liberal economy and, along with Munshi, joined the Swatantra Party. What they had in common, though, was that they were all prolific writers and firm advocates of a Uniform Civil Code as a fundamental right for all Indians.

When the Constituent Assembly began its proceedings in the run-up to Independence, they were the first ones, as part of the Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee, to make an onslaught on personal laws and orthodox practices and insist that all 400 million Indians of the time be governed by a single civil code.

In March 1947, Ambedkar and Munshi placed their individual drafts before the 12-member panel which included such a code as a justiciable right that is, a right that free India's courts could enforce Ambedkar stated all citizens must be able “to claim full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by other subjects regardless of any usage or custom based on religion and be subject to like punishment, pains and penalties and to none other“.In the same month, he publicly issued a memorandum on his idea of the Constitution that said “no person shall be permitted to refuse any obligation of citizenship on the ground of caste, creed or religion“. This was as unequivocal as it could get: personal laws had to be a thing of the past.

Munshi wrote, “No civil or criminal court shall, in adjudicating any matter or executing any order, recognise any custom or usage imposing any civil disability on any person on the ground of his caste, status, religion, race or language“. Minoo Masani said it was the state's duty to bring in a uniform code so “these watertight compartments“ (personal laws) could go.

The recommendation received the support of the two women on the panel Hansa Mehta and Rajkumari Amrit Kaur but was still outvoted, not so much because the members disapproved of it but because they felt the matter was “beyond the subcommittee's competence“. But only a couple of days later, the panel voted for inclusion of the clause in a new section of rights that was to be now created. To be called Directive Principles of State Policy, this section would contain rights not enforceable by courts. It was intended as a “guide“ for the state, and the provision framed by the panel read: “The state shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a unifor m civil code“. No timeframe, no deadline, and of course, no legal recourse.

The sub-committee explained in its draft report submitted to the advisory committee that “rights not capable of, or suitable for, enforcement by legal action, were named non-justiciable“. It cited the example of a clause which called upon the state to “endeavour to secure a decent standard of life for all workers“ and said it was impossible for a worker to establish, and for a court to prove, that such a right had been violated. A unifor m code was not so vague a notion; it had obviously been deemed `not suitable' for enforcement.

Why? “The reason... was not, as it might at first appear, the wish to avoid a clash with Hindu orthodoxy, but a sensitivity, particularly on Nehru's part, to the fears of the Muslims and the Sikhs,“ wrote the Indian Constitution's famous historian, Granville Austin.

Nehru had concerns that Muslims had bought Jinnah's claim that Congress rule meant “Hindu domination“, and he saw the Muslim League's boycott of the assembly as one more reason why the statute-making body, largely comprising Congress leaders, must appear all-Indian and reflect the party's position about safeguards for minorities.The League had won all seats reserved for Muslims in the central assembly polls of 1946, while Congress had won 91% of the others; and in the provincial elections the League had bagged 439 of 494 `Muslim' seats while Congress had clinched most of the rest. Besides, communal riots had singed Bengal in August '46 after Jinnah's call for `Direct Action', with mainly Hindus as victims, and had later spread to Bihar and Punjab, where Muslims and Sikhs had been targeted. Nehru visited Bihar and was “appalled by the brutality of Hindu mobs“.

By March 1947 when the rights panel met to discuss drafts the Congress Working Committee had realised Bengal and Punjab may have to be split, and by June the Indian leaders had accepted Mountbatten's Partition plan, including the date of transfer of power which he had brought forward from June 1948 to mid-August '47. While Nehru said in his broadcast to Indians in June that he had “no joy“ because of the planned division and violence, and while Congress's dream of one nation-state lay shattered, “on the other hand it gave it the prospect of a strong state with the potential for major socio-economic change, and acknowledged the legitimacy of the Constituent Assembly as the constitution-making body for much of India“, wrote his biographer, Judith Brown.

The feisty women on the rights sub-committee, Amrit Kaur and Hansa Mehta, along with Masani, wrote a letter to Sardar Patel, head of the advisory committee, in July '47, saying the clause on a uniform code be moved to the section on justiciable rights as “one of the factors keeping India back from advancing to nationhood was the existence of personal laws“. The letter also addressed the question of Muslim fears saying “in view of the changes that have taken place since (meaning approval of Partition) and the keen desire that is now felt for a more homogenous and closely-knit Indian nation“, the advisory committee should consider the matter afresh.

The minorities sub-committee, which also examined the matter, said a common code should be made “entirely voluntary“ and suggested the clause on it in the Directive Principles be reworked accordingly .

When the advisory committee met, it supported Kaur and Mehta's recommendation that the Principles, though not cognisable by courts, be considered “fundamental principles of governance“ and said so in its supplementary report submitted to the assembly on August 25, '47. But the clause on superseding personal laws stayed in the nonenforceable section.

The drafting committee, chaired by Ambedkar, accepted the provisions approved by the Patel-headed panel and made them a part of the Draft Constitution of 1948. The debate on justiciable and nonjusticiable rights would take place as priority in the assembly in November '48, when Ambedkar would place his draft before the House for consideration. As it turned out, the provision on a secular civil law would prove to be highly contentious.

1948: allaying Muslim fears

Fourth and last in a series on the Constituent Assembly debates on a Uniform Civil Code

After many Muslim members in the Con stituent Assembly had vociferously opposed the Uniform Civil Code, it was the turn of proponents of the `one nation, one law' idea to mount their opposition to personal laws held sacrosanct by a mostly tradition-bound Indian society .

They had a lot to think of before attacking religious customs. November 1948, when the debate on the clause in the Draft Constitution took place, was a sensitive time in terms of HinduMuslim ties. Though Partition-linked violence had stopped, the scars were fresh, thousands still dispossessed, and tensions hardly below the surface. Pakistan's act of sending Pathan invaders into Kashmir in October 1947, and PM Nehru's reference of the matter to the UN had complicated matters; Gandhi had been assassinated in January by a Hindu from Pune who felt that while Hindu grievances had gone unaddressed, the Mahatma had gone on a fast for release of Rs 55 crore from RBI's cash balances to Pakistan; the Nehru-Patel divide was growing (Patel was Deputy PM), with many within the Congress, including Nehru's friend PD Tandon and JB Kripalani, thinking the PM was disregarding the fears of Hindu refugees while “rallying minorities“; Nehru was uneasy with what he saw as increasing Hindu sentiment within his own party; and the Muslims who had refused to go to Pakistan hoped for assurances on safety as they feared a reaction from Hindus upset with brutalities inflicted on their co-religionists who had fled Lahore and Karachi.

The Muslim Assembly members had argued a common code would be “tyrannical,“ violate their basic right to practise religion (Article 19), infringe on immutable personal laws which had for ages been an integral part of their religion, “trample upon“ minority rights and hurt communal harmony. They had asked why free India wanted to change these laws when the British hadn't and cited the opposition of some Hindu groups to the provision, saying it was not they alone who had a problem with it.

Three Assembly members Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar from Madras and K M Munshi and B R Ambedkar from Bombay (Ambedkar, drafting committee head, was now also law minister) responded to each of these points in detail.

Munshi said that Article 19 allowed the state to enact social reform laws while protecting the freedom to practise religion, so it was not being contravened. A common code certainly wasn't tyrannical to minorities, in his view; civil laws framed in “advanced Muslim countries“ like Turkey and Egypt had not allowed minorities to retain their laws, and in Europe, all groups had to submit to secular laws.

In India, he added, the Khojas and Kutchi Memons had followed Hindu customs for generations but were brought within the ambit of the Shariat Act “unwillingly“ by the Central legislature in 1937.“Where were the rights of minority then?“ he asked.

His point, however, was larger: to unify the country , personal law had to be divorced from religion. Urging his “Muslim friends“ to forego an “isolationist outlook,“ Munshi said, “Religion must be restricted to spheres which legitimately appertain to religion, and the rest of life must be regulated, unified and modified in a such a manner that we may evolve, as early as possible, a strong and consolidated nation.“ He questioned the link between faith and community laws. Most provisions of the Hindu code draft (of 1946) ran counter to Manu and Yagnyavalkya's injunctions as social relations and inheritance were matters for secular legislation. Hindu laws discriminated against women and would not allow for elevating their position, so you could never give them equality though it was a fundamental right, he noted.

The idea that personal law was part of religion was “fostered“ and “perpetuated“ by the British and British courts, Munshi said, explaining why the British had retained community rules. “We must, therefore, outgrow it,“ he stressed.Ayyar said cries of “religion in danger“ and of lack of amity if a code were made binding were meaningless because the clause was “aimed at amity“ and welding India into one nation. “Is this country always to be kept as a series of competing communities?“ he asked.Those backing Hindu law reform had also taken a leaf from the Muslims and from other legal systems, he said, and asked why “our Muslim friends“ needed to have greater faith in the British than in a democracy that respected all religious beliefs. No Parliament or legislature would try to interfere with religious tenets, he felt, because, “after all, the only community willing to adapt itself to changing times seems to be the majority community in the country .“

Ambedkar, who spoke next, said he was “surprised“ a Muslim member had asked if a uniform code was possible and desirable in a vast country. “We have in this country a uniform code of laws covering almost every aspect of human relationship,“ he pointed out. “We have a uniform and complete criminal code... We have the law of transfer of property...I can cite innumerable enactments which would prove that this country has practically a civil code, uniform in its content and applicable to the whole of the country.“

Refuting the claim that Muslim personal law was immutable, he said until 1935 Muslims in the North-West Fron tier Province were not subject to Shariat, and those in the United Provinces, Central Provinces and Bombay were “governed by Hindu law in the matter of succession.“

In North Malabar, he said, they had even followed the matriarchal Marumakkathayam law.

At the same time, Ambedkar wanted to give the Muslims an assurance. There was nothing in the draft Article 35 to support the view that once it was framed, the state would enforce a uniform code upon all citizens merely because they were citizens. It was perfectly possible, he said, that a future Parliament may make a provision that, as a beginning, the code would apply only to those who declared they were prepared to be bound by it. So initially the code “may be purely voluntary ,“ he said.

Ambedkar was making a compromise in view of the national situation. His position became clearer a few days later, when he said he didn't understand “why religion should be given this vast, expansive jurisdiction so as to cover the whole of life and to prevent the legislature from encroaching upon that field.“

He said “we must all remember including members of the Muslim community who have spoken on this subject, though one can appreciate their feelings very well that sovereignty is always limited... because (it) must reconcile itself to sentiments of different communities.“

Yet he, Munshi and Ayyar were relieved when, immediately after the heated debate, amendments to Article 35 moved by five Muslim members were negative by the Assembly and a uniform code incorporated into the Constitution. And there it stays today as a Directive Principle, neither enforceable by law nor voluntary , a letter that is yet to be brought to life.Next|Laws for women, not against Muslims

Ambedkar’s gradualist approach

Pradeep.Thakur, June 28, 2023: The Times of India

Faced with opposition from a few members, mainly Muslims, of the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar recommended gradualism. “It is perfectly possible that the fu-ture Parliament may make a provision by way of making a beginning that the Code shall apply only to those who make a declaration that they are prepared to be bound by it, so that in the initial stage, the application of the Code may be purely voluntary so that the fear which my friends have expressed here will be altogether nullified. This is not a novel method. It was adopted in the Shariat Act of 1937 when it was applied to territories other than the North-West Frontier Province. The law said that here is a Shariat law which should be applied to Mussalmans who wanted that he should be bound by the Shariat Act, should go to an officer of the state, make a declaration that he is willing to be bound by it, and after he has made that declaration, the law will bind him and his successors,” Ambedkar had said.

“Before the Shariat Act 1937, Muslims in many parts were governed by Hindu lawand even Marumakkathayam system of inheritance and succession which had been prevalent in many of the southern Indian states,” Ambedkar further said. A consensus eluded the Constituent Assembly primarily because members feared that UCC “would coexist alongside personal law systems, while others thought it was to replace personal law”. There were also apprehensions that it would lead to denial of freedom of religion. This led the Constituent Assembly to safely place the matter of UCC under Article 44 among the Directive Principles.

Among other significant arguments put forth by the law panel in its consultation paper in support of UCC was the Ahmed Khan vs Shah Bano judgment. “The court in Shah Bano observed, ‘Article 44 of our Constitution has remained a dead letter. There is no evidence of any official activity for framing a common civil code for the country. A common civil code will help the cause of national integration by removing disparate loyalties to laws which have conflicting ideologies. It is the state which is entrusted with the duty of securing a uniform civil code for the citizens of the country and, unquestionably, it has the legislative competence to do so. A beginning has to be made if the Constitution is to have any meaning,’” the paper said.

1948: group opposes interference with ways of living of communities

The third of a four-part series on Constituent Assembly debates

A multi-community group in the Constituent Assembly that included a Dalit (B R Ambedkar), a devout Hindu (K M Munshi), a Parsi (Minoo Masani), a second-generation Sikh who converted to Christianity (Rajkumari Amrit Kaur) and a Gujarati Nagar Brahmin (Hansa Mehta) had hopes that a Uniform Civil Code would be incorporated in the Indian Constitution as a fundamental right and not merely as one of the non-justiciable Directive Principles of State Policy . At the same time, another group, wholly Muslim, was determined to vigorously put forth its case for the exact opposite: it wanted personal laws to be treated as a fundamental right and therefore enforceable in any court of law.

Soon after the Assembly started debating Ambedkar's Draft Constitution in November 1948, three amendments to the clause on the Code included in the Directives were tabled by five Muslim members -Mohammed Ismail Khan, Naziruddin Ahmad, Mahboob Ali Baig, B Pocker Sahib and KTM Ahmed -with a view to ensuring that no community would be made to give up its own laws if it didn't wish to. In what The Times of India of November 24, 1948, described as “a series of full-blooded speeches,“ these five (earlier part of the Muslim League Assembly Party), posing “as spokesmen of the minority community ,“ denounced the provision of a common law as “tyrannical“.Their refrain all through the impassioned debate was that if the British had not touched religious laws, especially those related to marriage and inheritance, “for 175 years,“ what was the need for the newly-independent Indian nation-state to do so? One key argument they made was that Article 35 (related to the UCC) clashed with Article 19 that gave all citizens the right to practise religion and said if it were enacted, it would tantamount to “interfering“ in the ways of living of communities. “The personal law was so much dear and near to certain religious communities,“ Mahboob Ali Baig said, and “as far as the Mussalmans are concerned, their laws of succession, inheritance, marriage and divorce are completely dependent on their religion.“ B Pocker Sahib said if these “religious rights and practices“ were infringed upon, it would be “tyrannical.“ Any uniformity in legislation would serve just one purpose, he stressed -it would “murder the consciences of people and make them feel they are being trampled upon.“

Mohammed Ismail Khan felt that though the Assem bly's intention seemed to be “to secure harmony through uniformity ,“ given the recent communal troubles and the Partition that India had gone through, it would actually “bring discontent“ and hurt harmony . Agreeing with him fully, Naziruddin Ahmad warned of widening “misunderstanding and resentment“ and echoed his co-religionist members' view that “what the British in 175 years failed to do or were afraid to do... we should not give power to the State to do all at once.“

In a reply to a statement made by member M Ananthasayanam Ayyangar that marriage in Islam was in the nature of a contract, Baig underlined the primacy of religion, saying, “I know that very well, but this contract is enjoined on the Mussalmans by the Quran and if it is not followed, a marriage is not legal at all. For 1,350 years this law has been practised by Muslims and recognised by all authorities in all states. If today Mr Ayyangar is going to say that some other method of proving marriage is going to be introduced, we refuse to abide by it because it is not according to our religion. It is not according to the code laid down for us for all times.“

B Pocker Sahib sought to expand the ambit of the argument, saying that many Hindu groups too had objected to a common law and had used “stronger language“ against it. But even if the majority community was in favour of Article 35, he emphasised, it had to be “condemned“ because the majority could not ride roughshod over minority rights but had a duty “to secure the sacred rights of every minority .“

Two Muslim members, Ahmad and Hussain Imam were, in addition, convinced the time was just not right to bring in a binding legislation for all of India. It could be introduced only when mass illiteracy had been wiped out, people had “advanced,“ and their economic conditions improved, they stated. Would it not be odd to apply the same kind of law for “the advanced people of Bombay“ and for parts of the country which were “very , very backward,“ they asked. Besides, the progress towards a uniform code should be “gradual and with the consent of the people concerned“ so that religious laws were not affected, they insisted. Mohammed Ismail Khan also said the matter was not all about Muslims. Of course, several European constitutions (such as Yugoslavia's, for instance) allowed Muslims to follow their own laws, but they dealt mainly with minority rights. The amendment he had proposed, he said, referred not to minorities alone but to all, including the majority, and thus aimed at securing everybody's rights.

Democratic pluralism prevailed

Oct 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 3, 2021: The Times of India

Should India have a uniform civil code, a set of common family laws on marriage, separation, adoption, inheritance and so on? Currently, the personal laws of each religious community apply to these domains, while the state can intervene to protect fundamental rights of the individual. In the Constituent Assembly debates, several people argued for a UCC, including those who cared about ending gender discrimination, those who felt that personal laws divided the nation, and those like BR Ambedkar, who wanted to restrict the scope of religion.

It also had many opponents. In the backdrop of Partition, the Muslim minority was worried about their cultural autonomy being swamped by the new Indian state, and they argued for all communities to have religious freedom within a secular state. There was also intense pushback from orthodox Hindus, whose practices were set to be reformed and codified. Many defended their practices, including untouchability, and said the state had no right to intervene in dharmas and shastras. Ultimately, democratic pluralism prevailed.

Instead of enacting a Uniform Civil Code, the Constituent Assembly made it a directive principle of state policy. It was merely a guideline, an aspiration with no legal enforceability. While Muslim law had been significantly reformed in the 1930s, before the Constituent Assembly debates, there was uproar, however, over codifying Hindu family laws. Ambedkar eventually resigned, while Nehru had to win a new election to find the legitimacy to enact the Hindu Code bills in piecemeal form.

The Shah Bano case/ 1985

The highlights, recorded by Mr Arghya Sengupta

April 23, 1985. In an otherwise routine case, the Supreme Court of India ordered Mohd. Ahmed Khan to pay his wife Shah Bano Rs 179.20 per month as maintenance. Khan had expelled Shah Bano, his wife of 43 years, from their matrimonial home and married a younger woman. Based on his understanding of Islamic law, he paid her a small maintenance for a few years combined with a one-off payment of mehr. When she went to a magistrate asking for an increase in maintenance, Khan divorced her and claimed he owed her nothing further. The matter ended up in the Supreme Court because Khan claimed the Code of Criminal Procedure under which she had asked for maintenance did not apply in the case of a Muslim man who had divorced his wife. To him, it was a matter purely in the domain of Muslim personal law. …

[A] Muslim woman who had been given a talaq by her husband had a right to approach a magistrate under the Criminal Procedure Code and demand maintenance. Several judgments of the Supreme Court had earlier adopted the same view. It was unsurprising that in this case too the Supreme Court decided likewise, stating almost peremptorily that “this case does not involve any question of constitutional importance”…

[The case] managed to strike a raw nerve for an entirely unexpected reason — the well-intentioned [from Mr Sengupta’s point of view] but gratuitous advice offered by the Supreme Court to enact a uniform civil code as envisaged by Article 44 of the Constitution…

But apprehensions expressed by five prominent Muslim members and the absence of a clear understanding of the contents of the code meant that a compromise was reached instead. Article 44 of the Constitution exhorted the state to “endeavour to secure” a uniform civil code sometime in the future...

With the re-emergence of the issue of enacting the code in the Shah Bano judgment, the Muslim Personal Law Board went into overdrive. The Board, whose very existence was at stake and which had actively supported Khan’s petition, gave a rallying call to Muslims to save Islam from being overrun. Their successful advocacy meant Rajiv Gandhi, who initially had appeared to support the judgment, performed a volte-face and enacted the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986 to ostensibly overturn it. As a matter of fact, the law did not achieve this objective. But combined with the judgment, it had a far deeper impact.

With prominent Muslim voices lending their weight to the view that the uniform civil code would be an expression of the tyranny of the majority, the Bharatiya Janata Party repositioned itself not only as the protector of Hindu interests, but also as a party that opposed appeasement politics of its so-called ‘secular’ counterparts. This was the shift the Supreme Court unwittingly set in motion — secular parties in India, with the significant exception of the Left parties, did not support [the] judgment…

In 1992, in the bylanes of Indore, something less earthshattering happened. Shah Bano died of a brain haemorrhage. Despite having won her legal battle, she abjured her winnings, ostensibly to smoothen the rifts it had caused within her community. The judgment that bears her name did little for her. But it continues to exercise a disproportionate influence on Indian politics.

B

Dhananjay Mahapatra, June 29, 2023: The Times of India

New Delhi: The decision of advocate Mohd Ahmed Khan, with an annual income of Rs 60,000 in the 1970s, to move the Supreme Court opposing award of a monthly alimony of Rs 179 to hi s wife Shah Bano, abandoned after 43 years of marriage, p ut the spotlight on Article 44 of the Constitution envisioning Uniform Civil Code for the country.

Married to Khan in 1932 an d driven out of her matrimonial home in 1975, Bano approached an Indore court in April 1978 seeking Rs 500 as monthly maintenance allowance. Khan gave her talaq in November 1978. In August 1979, the magistrate awarded her a beggarly sum of Rs 20 per month. On her appeal, the Madhya Pradesh HC enhanced it to Rs 179. 20. Khan challenged it before the SC.

A five-judge SC bench led by then CJI Y V Chandrachud in April 1985 upheld the maintenance granted by the HC with a direction to the husband to pay an additional sum of Rs 10,000 as cost to Bano. The HC’s ground-breaking observations on UCC, delivered in the case, continue to stir political waters.

The SC had said, “It is also a matter of regret that Article 44 of our Constitution has remained a dead letter. There is no evidence of any official activity for framing a common civil code for the country. A belief seems to have gained ground that it is for the Muslim community to take a lead in the matter of reforms of their personal law. A common civil code will help the causeof national integration by removing disparate loyalties to laws which have conflicting ideologies.

“No community is likely to bell the cat by making gratuitous concessions on this issue. It is the State which is charged with the duty of securing a Uniform Civil Code for the citizens of the country and, unquestionably, it has the legislative competence to do so. A counsel in the case whispered, somewhat audibly, that legislative competence is one thing, political courage to use that competence is quite another. We understand the difficulties involved in bringing persons of differen t faiths and persuasions on a common platform but a beginning has to be made if the Constitution is to have any meaning. ”

The bench severely criticised the All India Muslim Personal L aw Board for siding with the husband and quoted from a report of the Commission on Marriage and Family Laws in Pakistan in the late 1950s expressing grave concern over a large number of middle-aged women being divorced “without rhyme or reason” in the country and being rendered destitute. The report of the Pakistani commission had concluded, “The question whi ch is likely to confront Muslim countries in the n ear future i s whether the law of Islam is capable of evolution — a question which will require great intellectual effort and is sure to be answered in the affirmative. ” But it is the very question which continues to stifle reforms in Muslim per- sonal laws, which remain uncodified even after 73 years of India becoming a republic and 67 years after Hindu personal laws were codified.

Instead of attempting to bring in UCC, the Rajiv Gandhi government enacted the Muslim Women (Protection of Right on Divorce) Act, 1986 to annul the impact of the Shah Bano judgment. Though the SC upheld the validity of the 1986 Act, it continued to rule undeterred — in Danial Latifi (2001), Iqbal Bano (2007) and Shabana Bano (2009) cases — that Muslim women could not be deprived of the benefit of Section 125 of CrPC mandating husbands to pay alimony to wives. The SC remained quiet for nearlya deca de during which it dismissed a writ petition filed by Maharishi Avadhesh (1994) challenging the 1986 law and seeking enactment of a common civil code, or codifying Muslim personal lawsaying, “These are all matters for the legislature. ”

In the Sarla Mudgal judgment of 1995, the SC was more forthright in insisting that the legislature take steps to enact UCC. It ha d said, “Where more than 80% of citizens have already been brought under codified personal law, there i s no justification whatsoever to keep in abeyan ce, any more, the introduction of uniform civil code for all citizens in India. ” The SC, again in 2003 in John Vallamattom case, highlighted the desirability of achieving the goal set by Article 44 of the Constitution.

On March 29 this year, the SC had dismissed a PIL seeking enactment of UCC. It had reiterated what it had said in 1994, “Approaching this cou rt for enactment of UCC is akin to moving a wrong forum. It falls within the exclusive domain of Parliament. ”

Uniform Civil Code: A backgrounder, as in 2021 July

Sushmita Choudhury, July 15, 2021: The Times of India

The judge making this request said that such a law will help the courts and the common people who have “been repeatedly confronted with the conflicts that arise in personal laws”. The court’s observations came while hearing an estranged couple’s plea for divorce where the wife had challenged the application of the Hindu Marriage Act.

The need for a Uniform Civil Code comes up every now and then, especially when there is a particularly sticky (and public) case regarding personal law, or if politicians want to score points.

But what is the Uniform Civil Code? In a nutshell, it is intended to be a common set of laws that govern personal matters such as marriage, divorce, maintenance, child custody, adoption and inheritance. Currently, there are different laws governing these aspects for different religious communities in India — the laws governing Hindus would be different from those pertaining to Muslims or Christians or Parsis.

The demand for a Uniform Civil Code means unifying all these "personal laws" under one set of secular civil laws that will apply to all citizens of India irrespective of their faith.

The background

It’s a long-standing demand, going back to the pre-Independence era. The All India Women’s Conference was the first to raise it back in the 1930s. Post-independence, India’s first law minister, B R Ambedkar, asked the Constituent Assembly to adopt a uniform code, but its Muslim members staunchly opposed it.

Eventually, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru felt that in light of the pre- and post-Partition violence, Muslims who had stayed back in India would feel insecure if a Uniform Civil Code was introduced immediately. He said such a code had his “extreme sympathy” but the time was not “ripe” for it.

So all Ambedkar managed to get in the Constitution was Article 44 in the Directive Principles that says “the State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code”. However, under Article 37 of the Constitution, the directive principles "shall not be enforceable by any court" although they are "fundamental in the governance of the country".

Enter the Supreme Court

For decades, demand for the Uniform Civil Code was pushed to the backburner, with the country dealing with several other momentous events. Then, in 1985, the Supreme Court resurrected the issue when ruling on the Shah Bano case. The court had then ruled that a Muslim woman was entitled to maintenance from her husband after divorce.

At the time, the bench had declared that a common civil code will help the cause of national integration by removing disparate loyalties to law which have conflicting ideologies, but the verdict met with a massive country-wide backlash from Muslim groups. Eventually, then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was compelled to overturn the ruling.

Since then, various judgements by the Supreme Court have made significant steps towards uniformity while stressing on the need for a Uniform Civil Code.

But, despite the push from the judiciary, successive governments have been unable to implement such a code, partly due to vote-bank politics, partly due to lack of consensus among the minority communities, and largely due to the complications involved.

In fact, it is rather ironic that the party championing a secular Uniform Civil Code is the BJP. But, despite it being included in the party’s manifesto for the 1998, 2014 and 2019 elections, it still remains to be implemented. Curiously, PM Narendra Modi has been reticent on the issue, despite the BJP’s massive majority in Parliament.

The case against

The main argument against a uniform personal law is that it’s a threat to the religious freedom envisaged by the Constitution. According to experts, the special provisions extended to northeastern states under Article 371A and the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution make it difficult to roll out a common law for the whole country.

In 2016, the Modi government directed the Law Commission to look into the feasibility of a uniform code. After two years of research and sifting through over 75,000 responses, the commission furnished a consultation paper — not a final report — on “Reform of Family Law” in 2018. According to the paper, in the absence of any consensus on a Uniform Civil Code, the “best way forward may be to preserve the diversity of personal laws, but at the same time, ensure that personal laws do not contradict fundamental rights”.

The commission urged the legislature to “first consider equality within communities between men and women rather than equality between communities”, adding that a Uniform Civil Code is “neither necessary nor desirable at this stage”.

The backdoor route

Even as politicians bicker and religious groups argue, the courts have been moving towards homogenising the myriad personal laws, one ruling at a time.

Over the years, several legislations have been passed, which when seen together suggest that the battle for a single family law to govern all personal relationships may already be partially won. Some of the early cases include the 1995 Sarla Mudgal case, where the court stopped the practice of conversion to Islam to facilitate bigamy, the 2003 John Vallamattom Case pertaining to the Indian Succession Act, and the 2017 Shayara Bano case when the instant Triple Talaq was declared unconstitutional.

Here’s a look at the more recent acts of Parliament and Supreme Court judgements that are geared towards uniformity:

2001: The Indian Divorce (Amendment) Act

This bill gave Christian women the right to seek marriage annulment by removing gender bias and removed the alimony ceiling clause, leaving it to the discretion of the district court to fix the quantum of maintenance. This amendment was seen as “a big leap forward towards the goal of a uniform divorce law”, according to a critique published in the Journal of the Indian Law Institute.

2005: Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act This law protects a woman from abuse by family members. It covers all women living in a household — wife, divorcee, widow, live-in partner, sister, mother — from actual or threats of abuse, whether physical, sexual, verbal, emotional or economic. The act ensures umbrella protection to women, instead of making victims of abuse run from pillar to post seeking recourse under a plethora of laws.

According to experts, this is one of the most important pieces of legislation passed this century since it is not only the most comprehensive to date but is also independent of religion. This is an important point, given that the personal laws under all the faith have long been criticised as patriarchal and discriminatory. In 2018, the Bombay high court proved as much when it ruled that the act would also apply to Muslim women as much as those of any other community.

2005: Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act

This landmark amendment gave women equal rights in inheriting ancestral property. Prior to the amendment, a daughter ceased to be a coparcener in her father’s Hindu Undivided Family (HUF) after marriage.

But the tricky and unanswered question of whether this amendment was retrospective or prospective in nature had confounded various high courts for over a decade. Will a woman have equal rights to ancestral property if the patriarch was already dead in 2005 when the Act was enacted?

Then, in August 2020, the Supreme Court cleared all doubts about division of ancestral property. In a 121-page judgement, the top court laid out that since the rights to coparcenary are created at birth, it will be applicable to all daughters — even those born before 2005. Similarly, the right to succession equality will be enjoyed by a female child even if her father was not alive before the amendments were made.

2006: Prohibition of Child Marriage Act The PCMA was passed in order to eradicate the practice of child marriages, and while its enforcement has left much to be desired, this legislation was another attempt to move towards uniformity and overcome the inconsistencies in the religion-based family laws on this matter.

Unlike the earlier legislation, the Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929, under the new legislation, a child — defined as any male under the age of 21 years or any female under the age of 18 years — who has been married off has the option to go to court and get their marriage declared cancelled.

According to a Planning Commission report, the act overrides all provisions in Indian personal laws that would otherwise permit child marriage. However, different high courts in the country have passed contradictory rulings on the supremacy of the PCMA vs the personal laws over the past few years, compelling the Supreme Court to note in 2017 that the ambiguity exists since the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 and the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages and Divorce Act, 1939, were not suitably amended after the PCMA was enacted.

2019: The Personal Laws (Amendment) Act

In February 2019, the Rajya Sabha passed this secular bill removing leprosy as a ground for divorce or separation. This act amended five acts, each containing provisions related to marriage, divorce, and separation of Hindu and Muslim couples.

These acts — The Divorce Act, 1869, the Dissolution of Muslim Marriage Act, 1939, the Special Marriage Act, 1954, the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, and the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956 — all prescribe leprosy as a ground for seeking divorce or separation from the spouse.

2019: The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act

It all started with the Shayara Bano case ruling by the Supreme Court citicising the Islamic practice of talaq-e-biddat, or triple talaq, which offered an instant divorce to Muslim men. The apex court not only declared this practice unconstitutional in 2017, it also directed the government to regularise the proceedings of divorce as per Sharia or Islamic law.

Based on this direction, the government passed The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act in 2019. There has been a lot of flak regarding criminalising triple talaq, but most see this as a step towards a more gender-just law for Muslim women.

2021: Amendment to Uttarakhand Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act

In February, Uttarakhand became the first state in the country to give co-ownership rights to women in their husband’s ancestral property. The move by the BJP-led Uttarakhand government to amend the Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act is expected to impact around 35 lakh women in the state.

The ordinance was brought keeping in mind the large-scale migration by men seeking job opportunities, while women would be left behind to handle all land issues. So it aimed at giving women economic independence.

National unity paramount

The biggest argument for a Uniform Civil Code is that it is exigent for the promotion of national unity in a secular country like India. In order to achieve this goal, various divergent religious ideologies must merge into a common and unified code that will treat every person equally.

With such a code in place, litigation would decrease and the problem of overlapping provisions of the law would be solved. Proponents also argue that a Uniform Civil Code could put an end to gender discrimination, a common failing in many personal laws currently in place.

The personal laws of the various communities

See the page Personal laws: India

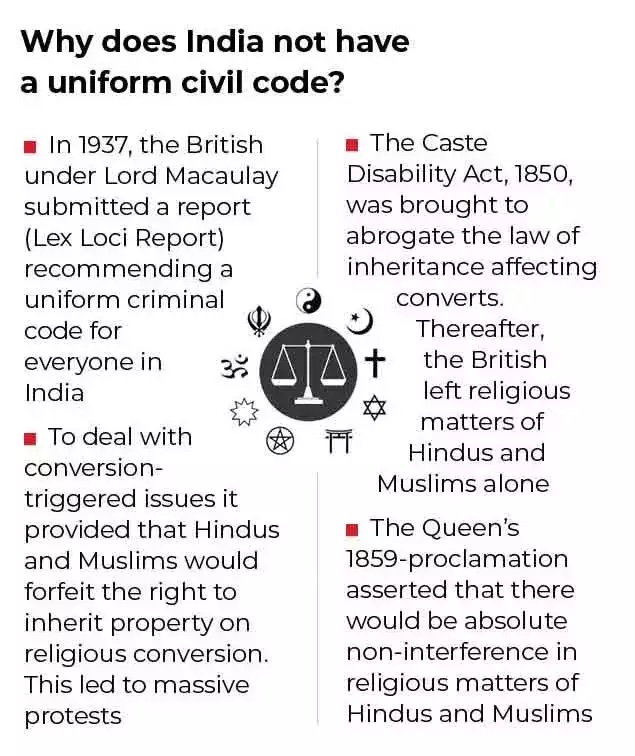

Why India doesn't have a uniform code

The issues

The Times of India, Aug 24 2017

From: Prabhash K Dutta, February 21, 2023: The Times of India

See graphic:

Why does India not have Uniform Civil Code?

Now that Supreme Court has made instant triple talaq illegal, the debate on personal laws is gaining centre-stage yet again.Should India allow each community its personal laws or should all Indians follow a uniform civil code? Personal laws deal in the main with family issues such as marriage, divorce, inheritance and are by and large skewed against women across communities and religions. Yet, some voices even from women's movements are wary about a uniform civil code.What is their say? Why is a uniform code desirable and what fears does it trigger? Here, a primer on the issue

What is Uniform Civil Code?

It was first raised as a demand in the 1930s by the All India Women's Conference, seeking equal rights for women, irrespective of religion, in marriage, inheritance, divorce, adoption and succession.

While the Constituent Assembly and Parliament considered such a Uniform Civil Code desirable, they did not want to force it upon any religious community in a time of strife and insecurity . They left it as a Directive Principle of the Constitution, hoping it would be enacted when the time was right.

Why does India have personal laws?

Each religious community in India has certain unique practices in family life, from marriage to inheritance and from marital separation to maintenance and adoption.Many of these are unfair to women, in different ways. India allows each community to practise its personal law, but these cannot violate constitutional rights.

There are also civil alternatives like the Special Marriages Act which any citizen can opt to follow.Under Ambedkar's stewardship, Hindu personal law was codified in the 1950s by Parliament, erasing distinct practices, though inequali ties between men and women still persist and custom prevails in some aspects. The majority religion is easier to reform; Pakistan, Bangladesh, etc. have reformed Muslim law while being cautious with Hindu practices. Indian lawmakers have also been more hesitant to change religious laws for minorities.

In 1986, the Supreme Court's Shah Bano judgment for maintenance was amended by Parliament, in a way that placated the Muslim clergy . Muslim personal law has not been codified by Parliament, except through the Shariat Act of 1937 and the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights of Divorce) Act of 1986. Judges have to rely on Islamic jurisprudence in a case-by-case manner. The Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan, which fought triple talaq in court, has sought codification of Muslim law to remove unjust practices.

Meanwhile, incremental change has happened over the decades.

Hindu succession was reformed by Parliament in 2005, and Christian divorce rights were made gender equal in 2001. The courts have steadily affirmed women's rights of maintenance, adoption, etc. in various judgments, strengthening reform in minority communities.

Who is pushing for a Uniform Civil Code?

There is vocal support for the idea from people with different motivations. Some feel that only the Hindu com munity has had its practices codified by Parliament so far and want minority practices to be similarly disciplined.

Some feel that secularism means taking out all traces of religion from family law and submitting to a single civil code that applies to all Indians in the same way . Some feel that all religious laws discriminate against women, and that the state owes its citizens a single, genderequal set of laws.

Who is against the Uniform Civil Code right now?

Many voices in the women's movement, people from minority communities, and others of a multicultural secular bent resist the Uniform Civil Code, saying that the state should push for uniform rights rather than a single code.

They call for rooting out gender bias within existing personal laws, rather than flattening religious difference under a code that they fear may be created in the mould of the Hindu majority .

They also argue for expanding civil alternatives like the Special Marriages Act, the Domestic Violence Act, the Juvenile Justice Act, etc. which apply to all women, irrespective of personal law. In their view, a Uniform Civil Code would be desirable only if it is fair to all communities, and not in a situation where minorities feel insecure.

What would a Uniform Civil Code look like?

An ideal Uniform Civil Code is easier to discuss than enact; there has never been a clear draft of such a code. It would have to restructure many laws, and forge a neutral standard. While polygamy and arbitrary divorce associated with Islam would go, so would the tax ben efits of the Hindu undivided family .Reservation would have to be extended to all religions. Distinctive practices of Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism might also have to end, in the domain of family law.

In some aspects, Muslim law is better for women, since they recognise individual rights to property, and because marriages are civil contracts with fixed obligations, rather than sacraments.

All these would have to be taken into consideration for a just Uniform Civil Code.

Nehru okayed principle, but didn't make it a directive

India's first PM Jawaharlal Nehru professed his keen desire to have a Uniform Civil Code (UCC), but though he succeeded in codifying Hindu law, his government took no step towards reform of Muslim personal laws and sidestepped the question of a common code altogether.

When Dr B R Ambedkar asked the Constituent Assembly to adopt a uniform code, its Muslim members staunchly opposed it, so all he got in the Constitution was Article 44 in the Directive Principles that said `the State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code.' The British had left Muslim laws untouched but had prepared a draft for reform of Hindu laws in 1946 in the wake of a robust Hindu social reforms movement. In 1948, Nehru asked Ambedkar, the first law minister, to head a panel that would work on this draft and finalise a Hindu code (which would apply also to Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs). When Ambedkar felt Nehru wasn't pushing the code through, he quit the Cabinet in 1951. After Nehru won a thumping win in the 1952 general elections, the Hindu Code Bill was revived, though by then it was split into many parts (relating to marriage, divorce, inheritance etc).

While the R-S-S saw in it an assault on Hindu tradition and many swamis quoted from the scriptures to show, for instance, how Hindu marriages were sacrosanct and indissoluble, the political opposition, right-wing as well as the Left, attacked Nehru's government, asking why the code wasn't an `Indian' one. Dr Shyama Prasad Mookerjee of the Jana Sangh said, “I know the weaknesses of promoters of this bill. They dare not touch the Muslim minority . There will be so much opposition coming from throughout India that government will not dare to proceed with it. But of course you can proceed with the Hindu community in any way you like and whatever the consequences may be.“

The Hindu Mahasabha's N C Chatterjee questioned the need for a `Hindu' Marriage Act if India was a secular nation. And if polygamy was bad, “why not rescue our Muslim sisters from that curse and plight?“ Socialist leader JB Kripalani said the government ought to bring in monogamy for Muslims too and added the community was “pre pared for it.“ His wife Sucheta Kripalani, a Congress MP, felt the Muslims weren't quite prepared but said she hoped the government would bring in a UCC “soon“. The Communists too wanted the personal laws of all communities to be reformed; B C Das and Bhupesh Gupta felt the reforms being undertaken weren't far-reaching enough.

Nehru believed that given the preand post-Partition violence, Muslims who had stayed back in India would feel insecure if a UCC was introduced immediately. He said the UCC had his “extreme sympathy,“ but the time was not “ripe“ for it. “I want to prepare the ground for it and this kind of thing (Hindu code) is one method of preparing the ground,“ he said. Muslim MPs then thanked him profusely for “protecting“ their personal laws.

The bills on reforming Hindu laws were passed in 1955-56, after which the UCC debate and the one on codifying Muslim law more or less died down. It resurrected itself in 1985-86 (by then Panditji had been dead for over 20 years and his daughter Indira, too, had passed away) when Nehru's grandson Rajiv overturned the SC verdict in the Shah Bano case.

1940s: ‘significant Hindu opposition to Uniform Civil Code’

In the 1940s, Muslim women had more formal rights than other communities.

That's why Hindu law was the first focus for reform

The dominant narrative about the Uniform Civil Code in the Constituent Assembly describes it as a compromise between equality and pluralism. While women members like Hansa Mehta and liberal egalitarians like Ambedkar advocated for state reform of family law, Muslim conservatives argued that this would impede their religious freedom. Muslim League members within the Constituent Assembly proposed amendments to exclude “personal law of the community“ from the operation of the Uniform Civil Code. The Jamaat-e-Ulema-e-Hind demanded specific provisions for protecting Muslim personal law from interference in the future Constitution.Given the need to ensure that Indian Muslims felt secure in a majoritarian secular leadership, the goals of equality and uniformity were deferred by placing the UCC within the non-implementable Directive Principles of State Policy . All the above facts are accurate.

However, this narrative both ignores the significant Hindu opposition to the Uniform Civil Code, as well as the fact that the impending reforms in the 1940s were in Hindu law. Muslim law had undergone significant legislative reform in the late '30s. In contrast to their Hindu and Christian sisters, under formal law Muslim women could inherit and hold property, maintain a separate legal identity from their husband, were required to give consent to marriages and could independently sue for divorce in the courts. The Muslim legislative reforms of the 1930s were remarkable because despite years of opposition to state interference, the community had used the instruments of the colonial state and secular lawmaking to change Muslim personal law.

Hindu reformers sought to find common ground in the language of equality and progress. Dr. G.V. Deshmukh who had authored several bills to give Hindu women the right to property was an enthusiastic supporter of the Shariat Act, noting that it abolished customary laws that prevented women from inheriting. He said that if “Mohammedan society progresses, in future every society in India will follow their example“. Radhabai Subbaroyan, the sole woman legislator, praised the Muslim members for granting women the same right to claim divorce and hoped they would be “guided by the sense of justice in all matters regarding women“, much to the alarm of Hindu conservative members.The Shariat Act was analogised to the UCC by K.M Munshi, who noted that it abolished the customs of several Muslim groups without their consent. Since Muslim law had recently been reformed, the main legislative reforms on the anvil in 1945 were the draft Hindu Code Bill and a slate of anti-untouchability and temple entry legislations. In 1931, the Indian National Congress had spelt out a constitutional vision that would use instruments of state to transform society and the economy .

In 1945, the All India Women's Conference had issued a Charter of Rights and Duties that placed family law reform as a major agenda. Sir B.N Rau and Dr Ambedkar, the two men most closely associated with drafting the Constitution, were also involved in heading the committee to reform the Hindu Code. The Hindu Code reforms and the Constitution were seen as joint projects. Orthodox Hindus and caste groups looked upon the debates on freedom of religion with foreboding and petitioned the Constitu ent Assembly demanding that the state not interfere with Hindu religious practice.

A petitioner from Madras expressed concern at the proposed abolition of untouchability, noting while “communal“ untouchability was bad, there are religious occasions (like bir ths, deaths and marriages) as well as the monthly periods of women when caste un touchability is required.

Other letters protested that the draft Constitution took away from the privilege of freedom of religion, by al lowing the state to intervene in any `secular activity' of a religious body . How could a secular government, not guided by religious princi ples, make laws on religious practice in the name of so cial welfare or to throw upon religious institutions to all communities? communities?

The Hindu Wom en's Association of Kumbakonam re minded the assembly that the “ceremonies, marriage, and social functions of Hindu are based on religion and guided by Sastric principles“ and only religious authorities could reform them. The Vaish nava Siddhantha Sabha noted that while the Congress had been crying for toleration and religious freedom, in practical work, it was intolerant in stat ing that religion would be sub ordinated to the general wel fare of the country. On the question of untouchability , the Sabha pleaded for tolerance of their orthodox views and com plained that orthodox Hindus were underrepresented in the Assembly . Coordinated resolu tions and petitions from across India protested the govern ment's interference in Hindu dharma and sastras without involving religious readers.

The All India Varnashrama Samaj Sangh argued that the Constitution should give the fundamental right to every person to live according to the tenets of their own scriptures.If a provision in the scripture was considered unfair to some members of the religion, it may not be overridden by the state and the remedy to such members was that they could leave the religion. They argued that any law that intervenes in religious practice had to be reviewed by a statutory body of religious experts who would decide whether the law was in conflict with the scriptures.

In the early years of Independence, the resistance to Hindu law reform became a chief plank of opposition to the government both from Congress members and the public. The first constitutional challenge to personal laws came not from a commitment to equality , but from a Hindu man who wanted to continue to practice polygamy . Therefore it is important to note that the deferment of the UCC was not only to accommodate Muslim sensibilities but in anticipation of a massive pushback from orthodox Hindus. It required Nehru to contest and win an election on the issue to gain the legitimacy to enact some piecemeal Hindu law reform.Legislative legitimacy remains key to the project of family law reform.

Muslim women had greater divorce, property rights than Hindu women until 1976, 2005

For any social reform to be effective, it must work with a community's values, not harshly supplant them

Many, including the prime minister, have welcomed the recent Supreme Court verdict in Shayara Bano v. Union of India that confirmed that courts would not recognize triple talaq (unilateral irrevocable male repudiation). After this, some have also revived calls to introduce a Uniform Civil Code. How far does this judgment reduce the gender inequalities in Muslim law? How legitimate is the inference that a UCC is the next logical step to equalise rights in the family?

Several high courts had invalidated triple talaq from 1978 onward. The Supreme Court upheld this in Shamim Ara v. Union of India (2002), making talaq's validity dependent on the man providing “good reasons“ and proof of having attempted spousal reconciliation. This invalidated most instances of unilateral repudiation that do not follow such a careful process. The Shayara Bano bench did not raise the bar for the validity of talaq, for instance by requiring either the wife's consent or judicial approval. Extra-judicial divorce remains more readily available to Muslim men than to Muslim women, who access it mainly through khula, which requires a qazi's approval and the husband's consent. India's Muslim law gives women less rights than men in other respects too. It gives women only half their brothers' share in family property, disentitles about a half of Indian Muslim women to inherit agricultural land, and allows polygamy but not polyandry . Hindu law also disadvantages women in various ways -for example, allowing families to jointly own property that is usually controlled by men, giving widows only limited shares of such property, and not limiting testamentary rights which are very often used to disinherit women.

Two judges on the Shayara Bano bench ventured in a new direction by requiring personal law to be compatible with the fundamental rights recognised in the Constitution, and assessing triple talaq to be contrary to these rights.But the court also relied on the divorce procedures recommended in the Qur'an, hadith that report the Prophet Muhammad to have considered triple talaq revocable, reputable commentaries, and legisla tion in many countries that abrogated triple talaq. In doing so, it followed the tendency of postcolonial Indian courts to rely on the laws, norms, and initiatives of the concerned groups, rather than constitutional rights or international legal principles alone, when reforming personal law. This approach is meant to reconcile the recognition of cultural norms in family life with constitutional values.

Imaginative courts could base themselves on Shayara Bano's call to assess personal law based on constitutional rights to either amend provisions that disadvantage women or press legislators to do so.This could realize the most important current civil society demands -the entitlement of all Muslim women to inherit agricultural land, the decomposition of jointly owned Hindu property into individual shares, the restriction of rights to will property, and the grant of equal shares to conjugal partners in matrimonial property .

While such changes would be valuable, the government's recent personal law initiatives misrepresent the development of personal law and community orientations. The government claims that Hindu law was changed based on constitutional values, but minority tutional values, but min laws were not; that greater Hindu support for reform drove the emphasis on changing Hindu law; and that Muslim backwardness is the main constraint to a UCC, which would best enable gender justice.

Contrary to this view, community reformist mobilisation helped Muslim women gain rights to inherit substantial family property and to judicial divorces in the 1930s, two decades before Hindu women did. Soon after independence, important Muslim leaders wanted to entitle women to inherit agricultural land and control their dower, restrict or end polygamy and talaq, and increase the minimum marriage age. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Naziruddin Ahmad, and Hussain Imam were open to a future UCC formed through the confluence of India's various religious traditions. Nehru and Ambedkar were disengaged from such Muslim initiatives, mistook Muslim demands to retain religious laws for resistance to changing these laws, and failed to change minority laws. The Hindu law reforms of the 1950s were not based on constitutional egalitarianism, but on the Mitakshara and Dayabhaga schools of Hindu law as colonial officials had understood them, commentaries on the dharmashastras, and regional and caste customs, as well as the Western model of marital monogamy .Although policymakers focused on changing Hindu law, due to the limited scope of these changes, Christian and Muslim women had greater rights than Hindu women to ancestral property until 2005, Muslim women had greater divorce rights than Hindu women until 1976, the inheritance rights of Muslim women remain most secure because Muslim law restricts testamentary rights to a third of one's property , and the matrilineal customary laws of certain Adivasi groups give women si groups give women more property rights.

Parliament and t h e c o u r t s h ave changed India's per sonal laws moderately to promote women's rights and individual liberties. Personal laws were changed more extensively in Tunisia and Morocco, demonstrating that group rights are compatible with egalitarian liberal reform. The basing of these reforms in Is lamic jurisprudence gained them broader support, ena bling the sustenance of re form. There was much opposi tion, by contrast, to the adop tion of the Swiss Civil Code in Turkey , which could be main tained only through periodic authoritarian rule. This indi cates that reforms are more often considered legitimate if they are based in the relevant group's norms in societies where many want group culture expressed in family life.