Turbans, headdresses, pagdis: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

An overview

May 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 22, 2023: The Times of India

Since time immemorial, headdresses have been identity markers for men across cultures and personality types. That long piece of cloth wrapped around a man’s head has been projected as the guardian of his honour and the measure of his chutzpah in our movies and popular literature. Despite the homo significans or meaning makers that we are, the semiotics of the paghdi remains among the least researched subjects.

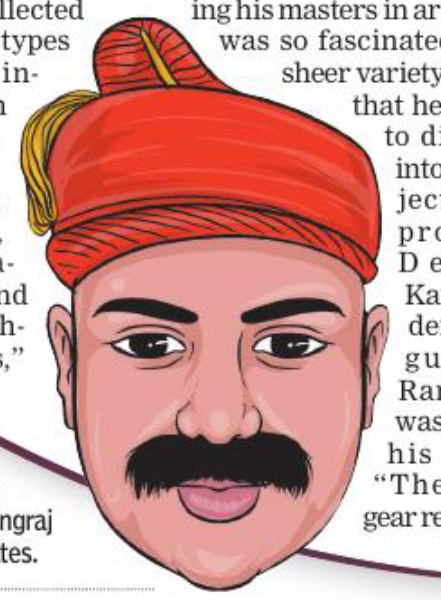

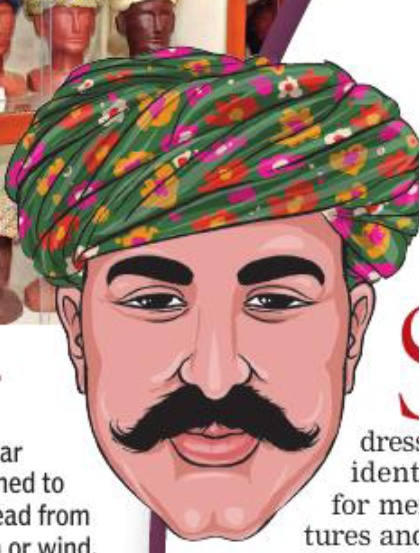

While almost every community has its own distinctive forms of headdresses — referred to as paghdi, pagota, feta or safa, depending on the region — they symbolize a much deeper meaning and differ in the way they are tied by different people and the colours worn. The paghdis stand for not only respect but also represent the wearer’s profession, status in society and the region he belongs to.

Awed by the sheer range of headdresses worn by different communities, the late Maharaja Ranjitsinh Gaekwad of Vadodara began collecting them a few decades ago. He also began his doctoral thesis on headdresses about a decade-and-a-half ago at the M S University of Baroda, but passed away before it could be completed. Ranjitsinh left behind a treasure trove of paghdis depicting the rich cultural diversity of our country, with each having interesting stories to tell.

“During his travels across the country, he collected over 152 different types of headdresses, including those worn by children. His collection includes a range of paghdis worn by Marwaris, Gujaratis, Rajasthanis and Maharashtrians,” said Manda Hingurao, the curator of Maharaja Fatehsingh Museum where the collection is on display.

“Ranjitsinh began collecting headdresses while pursuing his masters in arts and he was so fascinated by the sheer variety of them that he decided to dive deep into the subject,” said professor Deepak Kannal, under whose guidance Ranjitsinh was writing his thesis. “The headgear represents not only the region of the wearer, but also his religion and the caste. We have a huge variety of headdresses in India with subtle variations,” Kannal told TOI.

On the diversity in headgear types, Kannal said, “Brahmins, in many regions, wore rounded headdresses that were soft in the centre, while the Marathas wore the pagota made of a long piece of cloth. Variations were seen in the style of wearing the headgear even within the same community. The ‘tamashgirs’ (street-performers) wear the safa that is huge in size with one end of the cloth wrapped around the shoulder. ”

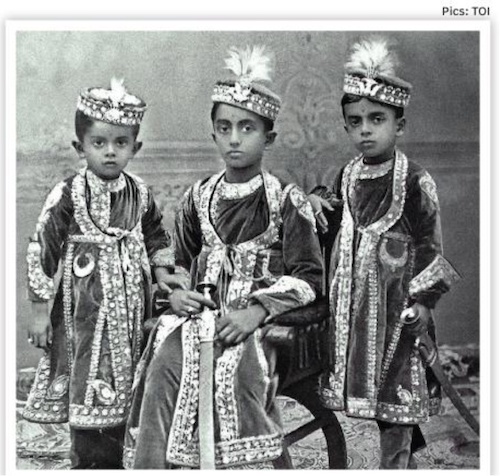

Kannal said that since the Mauryan era, the size of the headdress has come to depict the social status of the wearer. Kings and warriors wore relatively large paghdis compared to the traders and those involved in other professions. “The headdresses worn by most kings were decorated with jewels or feathers, depicting their social status. Shiva ji Maharaj modified the design of his headgear (called jirey top) to make it cone-shaped,” he added. “The Muslims wear skullcaps. So, when the Mughals arrived in India, they brought in a new style of headgear. They tied the turban around the skullcap. Their paghdis were embellished with embroidery work and jewels,” Kannal said.

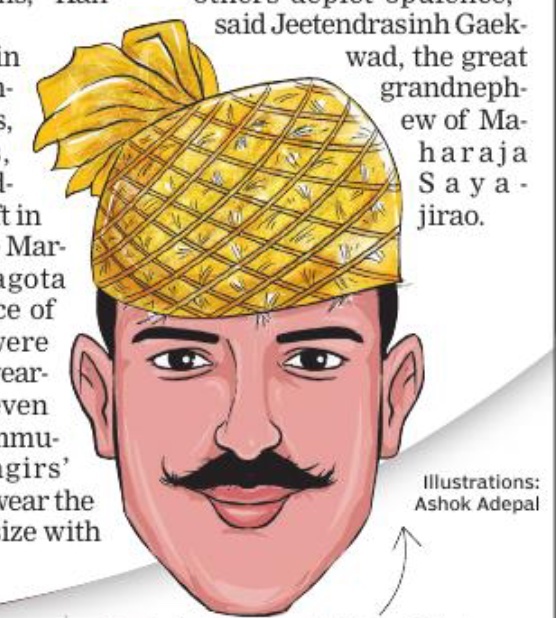

“In Gujarat alone, paghdis are worn in dozens of different styles. While some are designed to suit the weather, others depict opulence,” said Jeetendrasinh Gaekwad, the great grandnephew of Maharaja Sayajirao.

CULTURAL HERITAGE

The headgear was designed to protect the head from scorching sun or wind. Initially, these were made using leather or leaves, but gradually men began wrapping cloth around their heads in different styles. Turbans or headdresses have traditionally been symbols of cultural heritage. In many regions, the colour of the headgear differs with the changing seasons.

A SYMBOL OF PRESTIGE

The paghdi stands for honour and prestige in many communities. Kicking or trampling the headgear was considered an insult and offering one’s own to others was seen as a mark of respect. Entering a king’s court without a paghdi was not allowed in many princely states.

A TREASURE TROVE OF TURBANS

A 79-year-old Barodian boasts of having one of the largest collections of turbans in the country. Avantilal Chavla, a retired senior reader of the M S University’s dramatics department, has more than 200 turbans of various sizes. He was the first in India to earn a PhD for his thesis on turbans in 1989. His collection includes paghdis worn by the Gaekwads of Baroda, Maharaja Khengraj Sawai Bahadur of Kutch and Thakore sahebs of many princely states.

HOW CHAUHANS EXPRESS GRATITUDE TO BHILS

The Chauhans of Udaipur tie the headgear in a peculiar style during weddings in their family to honour the Bhils who helped them win battles. It’s an age-old tradition that continues even today — the bridegroom wears the Bhil headgear as a mark of respect to the community that once helped the Chauhans. The headgear is made from palm leaves and comprises a triangular cap with four long tassels. This particular sehra is made in Kothariya village for the Chauhan community.

Gaekwadi paghdis

May 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 22, 2023: The Times of India

The erstwhile Baroda state was one of the richest and most popular kingdoms during the British era and the visionary ruler, Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III, transformed it into a developed region. The dapper king, however, went from sporting a big paghdi to a smaller, more compact version.

Radhikaraje Gaekwad, the member of the royal Gaekwad family, has also described the fascinating Gaekwadi paghdis in her Instagram post.

‘In India every royal family had their own distinct headgear; in Baroda, we have the Gaekwadi paghdi. From its original length of 38 metres of narrow Chanderi fabric to the present day’s 21 metres, our paghdi has seen a few alterations over the centuries. Although sindoori red or crimson was usually the choice of colour, the Maharaja is said to wear green on Moharram and Eid,’ she posted. ‘From the more elaborate one of Maharaja Khanderao that accommodated his magnificent Sirpech and Turras (ariguette and pearl tassels) to Sayajirao III’s simple paghdi that he wore even with his Saville Row suits on his travels abroad, the Gaekwadi paghdi has many stories to tell.

Here’s an interesting fact: Maratha boys and men always sport a Gandha or a vermillion dot on their foreheads to accompany their headgear as an auspicious mark,’ she added.

The curved Gaekwadi cloth paghdi has a peculiar design with 16 tightly knitted threads in the front. “Earlier, it was a pagota but Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III went for a paghdi. He chose a design that made him look dapper,” said Jeetendrasinh Gaekwad, the great-grandnephew of Maharaja Sayajirao. On special occasions, jewellery or a feather adorned the king’s paghdi.

The current royal scion, Samarjitsinh Gaekwad, sported the royal paghdi with a turra and a jewel during his coronation ceremony in 2012 at Laxmi Vilas Palace.