Toda

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Toda

Quite recently, my friend Dr. W. H. Rivers, as the result of a prolonged stay on the Nīlgiris, has published an exhaustive account of the sociology and religion of this exceptionally interesting tribe, numbering, according to the latest census returns, 807 individuals, which inhabits the Nīlgiri plateau. I shall, therefore, content myself with recording the rambling notes made by myself during occasional visits to Ootacamund and Paikāra, supplemented by extracts from the book just referred to, and the writings of Harkness and other pioneers of the Nīlgiris.

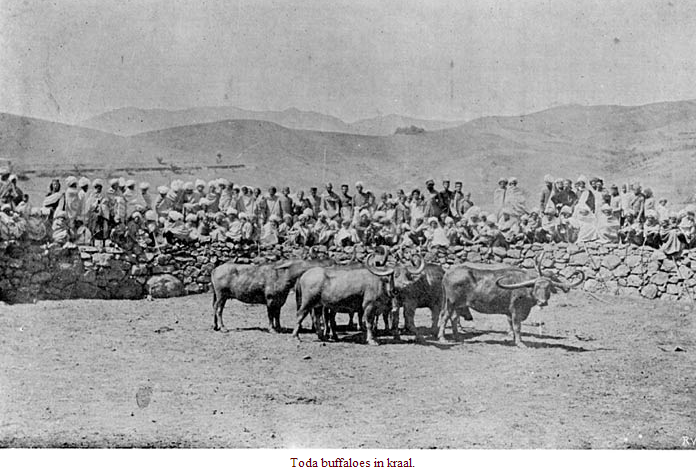

The Todas maintain a large-horned race of semi-domesticated buffaloes, on whose milk and its products (butter and ney) they still depend largely, though to a less extent than in bygone days before the establishment of the Ootacamund bazar, for existence. It has been said that “a Toda’s worldly wealth is judged by the number of buffaloes he owns. Witness the story in connection with the recent visit to India of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales. A clergyman, who has done mission work among the Todas, generally illustrates Bible tales through the medium of a magic-lantern. One chilly afternoon, the Todas declined to come out of their huts. Thinking they required humouring like children, the reverend gentleman threw on the screen a picture of the Prince of Wales, explaining the object of his tour, and, thinking to impress the Todas, added ‘The Prince is exceedingly wealthy, and is bringing out a retinue of two hundred people.’ ‘Yes, yes,’ said an old man, wagging his head sagely, ‘but how many buffaloes is he bringing?’”

The Todas lead for the most part a simple pastoral life. But I have met with more than one man who had served, or who was still serving Government in the modest capacity of a forest guard, and I have heard of others who had been employed, not with conspicuous success, on planters’ estates. The Todas consider it beneath their dignity to cultivate land. A former Collector of the Nīlgiris granted them some acres of land for the cultivation of potatoes, but they leased the land to the Badagas, and the privilege was cancelled. In connection with the Todas’ objection to work, it is recorded that when, on one occasion, a mistake about the ownership of some buffaloes committed an old Toda to jail, it was found impossible to induce him to work with the convicts, and the authorities, unwilling to resort to hard remedies, were compelled to save appearances by making him an overseer. The daily life of a Toda woman has been summed up as lounging about the mad or mand (Toda settlement), buttering and curling her hair, and cooking.

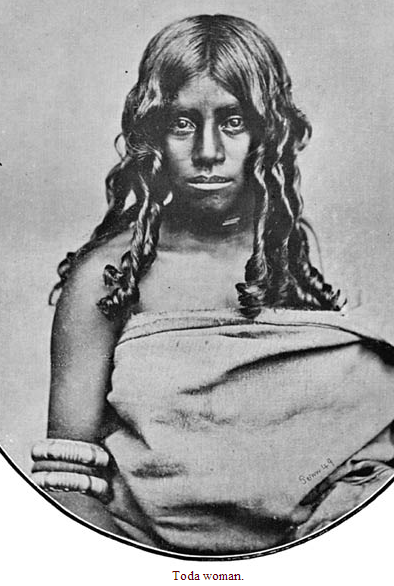

The women have been described as free from the ungracious and menial-like timidity of the generality of the sex in the plains. When Europeans (who are greeted as swāmi or god) come to a mand, the women crawl out of their huts, and chant a monotonous song, all the time clamouring for tips (inām). Even the children are so trained that they clamour for money till it is forthcoming. As a rule, the Todas have no objection to Europeans entering into their huts, but on more than one occasion I have been politely asked to take my boots off before crawling in on the stomach, so as not to desecrate the dwelling-place. Writing in 1868, Dr. J. Shortt makes a sweeping statement that “most of the women have been debauched by Europeans, who, it is sad to observe, have introduced diseases to which these innocent tribes were once strangers, and which are slowly but no less surely sapping their once hardy and vigorous constitutions. The effects of intemperance and disease (syphilis) combined are becoming more and more apparent in the shaken and decrepit appearance which at the present day these tribes possess.” Fact it undoubtedly is, and proved both by hospital and naked-eye evidence, that syphilis has been introduced among the Todas by contact with the outside world, and they attribute the stunted growth of some members of the rising generation, as compared with the splendid physique of the lusty veterans, to the results thereof. It is an oft-repeated statement that the women show an absence of any sense of decency in exposing their naked persons in the presence of strangers.

In connection with the question of the morality of the Toda women, Dr. Rivers writes that “the low sexual morality of the Todas is not limited in its scope to the relations within the Toda community. Conflicting views are held by those who know the Nilgiri hills as to the relations of the Todas with the other inhabitants, and especially with the train of natives which the European immigration to the hills has brought in its wake. The general opinion on the hills is that, in this respect, the morality of the Todas is as low as it well could be, but it is a question whether this opinion is not too much based on the behaviour of the inhabitants of one or two villages [e.g., the one commonly known as School or Sylk’s mand] near the European settlements, and I think it is probable that the larger part of the Todas remain more uncontaminated than is generally supposed.” I came across one Toda who, with several other members of the tribe, was selected on account of fine physique for exhibition at Barnum’s show in Europe, America and Australia some years ago, and still retained a smattering of English, talking fondly of ‘Shumbu’ (the elephant Jumbo). For some time after his return to his hill abode, a tall white hat was the admiration of his fellow tribesmen. To this man finger-prints came as no novelty, since his impressions were recorded both in England and America.

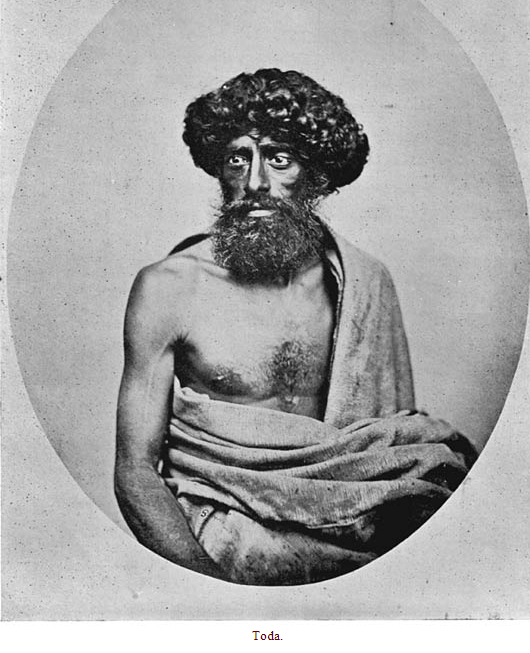

Writing in 1870, Colonel W. Ross King stated that the Todas had just so much knowledge of the speech of their vassals as is demanded by the most ordinary requirements. At the present day, a few write, and many converse fluently in Tamil. The Nīlgiri C.M.S. Tamil mission has extended its sphere of work to the Todas, and I cannot resist the temptation to narrate a Toda version of the story of Dives and Lazarus. The English say that once upon a time a rich man and a poor man died. At the funeral of the rich man, there was a great tamāsha (spectacle), and many buffaloes were sacrificed. But, for the funeral of the poor man, neither music nor buffaloes were provided. The English believe that in the next world the poor man was as well off as the rich man; so that, when any one dies, it is of no use spending money on the funeral ceremonies. Two mission schools have been established, one at Ootacamund, the other near Paikāra. At the latter I have seen a number of children of both sexes reading elementary Tamil and English, and doing simple arithmetic. A few years ago a Toda boy was baptised at Tinnevelly, and remained there for instruction. It was hoped that he would return to the hills as an evangelist among his people.35 In 1907, five young Toda women were baptised at the C.M.S. Mission chapel, Ootacamund. “They were clothed in white, with a white cloth over their heads, such as the Native Christians wear. A number of Christian Badagas had assembled to witness the ceremony, and join in the service.” The typical Toda man is above medium height, well proportioned and stalwart, with leptorhine nose, regular features, and perfect teeth. The nose is, as noted by Dr. Rivers, sometimes distinctly rounded in profile.

An attempt has been made to connect the Todas with the lost tribes; and, amid a crowd of them collected together at a funeral, there is no difficulty in picking out individuals, whose features would find for them a ready place as actors on the Ober Ammergau stage, either in leading or subordinate parts. The principal characteristic, which at once distinguishes the Toda from the other tribes of the Nīlgiris, is the development of the pilous (hairy) system. The following is a typical case, extracted from my notes. Beard luxuriant, hair of head parted in middle, and hanging in curls over forehead and back of neck. Hair thickly developed on chest and abdomen, with median strip of dense hairs on the latter. Hair thick over upper and lower ends of shoulder-blades, thinner over rest of back; well developed on extensor surface of upper arms, and both surfaces of forearms; very thick on extensor surfaces of the latter. Hair abundant on both surfaces of legs; thickest on outer side of thighs and round knee-cap. Dense beard-like mass of hair beneath gluteal region (buttocks). Superciliary brow ridges very prominent. Eyebrows united across middle line by thick tuft of hairs. A dense growth of long straight hairs directed outwards on helix of both ears, bearing a striking resemblance to the hairy development on the helix of the South Indian bonnet monkey (Macacus sinicus). The profuse hairy development is by some Todas attributed to their drinking “too much milk.”

Nearly all the men have one or more raised cicatrices, forming nodulous growths (keloids) on the right shoulder.These scars are produced by burning the skin with red-hot sticks of Litsæa Wightiana (the sacred fire-stick). The Todas believe that the branding enables them to milk the buffaloes with perfect ease, or as Dr. Rivers puts it, that it cures the pain caused by the fatigue of milking. “The marks,” he says, “are made when a boy is about twelve years old, at which age he begins to milk the buffaloes.” About the fifth month of a woman’s first pregnancy, on the new-moon day, she goes through a ceremony, in which she brands herself, or is branded by another woman, by means of a rag rolled up, dipped in oil and lighted, with a dot on the carpo-metacarpal joint of each thumb and on each wrist.

The women are lighter in colour than the men, and the colour of the body has been aptly described as of a café-au-lait tint. The skin of the female children and young adults is often of a warm copper hue. Some of the young women, with their raven-black hair dressed in glossy ringlets, and bright glistening eyes, are distinctly good-looking, but both good looks and complexion are short-lived, and the women speedily degenerate into uncomely hags. As in Maori land, so in Toda land, one finds a race of superb men coupled to hideous women, and, with the exception of the young girls, the fair sex is the male sex. Both men and women cover their bodies with a white mantle with blue and red lines, called putkūli, which is purchased in the Ootacamund bazar, and is sometimes decorated with embroidery worked by the Toda women. The odour of the person of the Todas, caused by the rancid butter which they apply to the mantle as a preservative reagent, or with which they anoint their bodies, is quite characteristic. With a view to testing his sense of smell, long after our return from Paikara, I blindfolded a friend who had accompanied me thither, and presented before his nose a cloth, which he at once recognised as having something to do with the Todas.

In former times, a Badaga could be at once picked out from the other tribes of the Nīlgiri plateau by his wearing a turban. At the present day, some Toda elders and important members of the community (e.g., monegars or headmen) have adopted this form of head-gear. The men who were engaged as guides by Dr. Rivers and myself donned the turban in honour of their appointment.

Toda females are tattooed after they have reached puberty. I have seen several multiparæ, in whom the absence of tattoo marks was explained either on the ground that they were too poor to afford the expense of the operation, or that they were always suckling or pregnant—conditions, they said, in which the operation would not be free from danger. The dots and circles, of which the simple devices are made up, are marked out with lamp-black made into a paste with water, and the pattern is pricked in by a Toda woman with the spines of Berberis aristata. The system of tattooing and decoration of females with ornaments is summed up in the following cases:—

1. Aged 22. Has one child. Tattooed with three dots on back of left hand. Wears silver necklet ornamented with Arcot two-anna pieces; thread and silver armlets ornamented with cowry (Cypræa moneta) shells on right upper arm; thread armlet ornamented with cowries on left forearm; brass ring on left ring finger; silver rings on right middle and ring fingers. Lobes of ears pierced. Ear-rings removed owing to grandmother’s death.

2. Aged 28. Tattooed with a single dot on chin; rings and dots on chest, outer side of upper arms, back of left hand, below calves, above ankles, and across dorsum of feet. Wears thread armlet ornamented with young cowries on right forearm; thread armlet and two heavy ornamental brass armlets on left upper arm; ornamental brass bangle and glass bead bracelet on left wrist; brass ring on left little finger; two steel rings on left ring finger; bead necklet ornamented with cowries.

3. Aged 35. Tattooed like the preceding, with the addition of an elaborate device of rings and dots on the back.

4. Aged 35. Linen bound round elbow joint, to prevent chafing of heavy brass armlets. Cicatrices of sores in front of elbow joint, produced by armlets.

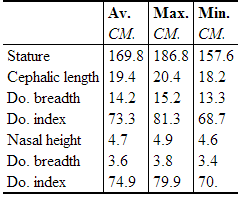

5. Aged 23. Has one child. Tattooed only below calves, and above ankles. The following are the more important physical measurements of the Toda men, whom I have examined:—

Allowing that the cephalic index is a good criterion of racial or tribal purity, the following analysis of the Toda indices is very striking:—

69 ◆◆

70 ◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

71 ◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆ ]

72 ◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

73 ◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

74 ◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆ 75 ◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆ 76 ◆◆◆◆◆◆ 77 ◆ 78 ◆ 79 ◆ 80 81 ◆ A thing of exceeding joy to the Todas was my Salter’s hand-dynamometer, the fame of which spread from mand to mand, and which was circulated among the crowd at funerals. Great was the disgust of the assembled males, on a certain day, when the record of hand-grip for the morning (73 lbs.) was carried off by a big-boned female, who became the unlovely heroine of the moment. The largest English feminine hand-grip, recorded in my laboratory note-book, is only 66 lbs. One Toda man, of fine physique, not satisfied with his grip of 98 lbs., went into training, and fed himself up for a few days. Thus prepared, he returned to accomplish 103 lbs., the result of more skilful manipulation of the machine rather than of a liberal dietary of butter-milk.

The routine Toda dietary is said to be made up of the following articles, to which must be added strong drinks purchased at the toddy shops:—

(a) Rice boiled in whey.

(b) Rice and jaggery (crude sugar) boiled in water.

(c) Broth or curry made of vegetables purchased in the bazar, wild vegetables and pot-herbs, which, together with ground orchids, the Todas may often be seen rooting up with a sharp-pointed digging-stick on the hill-sides. The Todas scornfully deny the use of aphrodisiacs, but both men and women admit that they take sālep misri boiled in milk, to make them strong. Sālep misri is made from the tubers (testicles de chiens) of various species of Eulophia and Habenaria belonging to the natural order Orchideæ.

The indigenous edible plants and pot-herbs include the following:—

(1) Cnicus Wallichii (thistle).—The roots and flower-stalks are stripped of their bark, and made into soup or curry.

(2) Girardinia heterophylla (Nīlgiri nettle).—The tender leafy shoots of vigorously growing plants are gathered, crushed by beating with a stick to destroy the stinging hairs, and made into soup or curry. The fibre of this plant, which is cultivated near the mands, is used for stitching the putkuli, with steel needles purchased in the bazar in lieu of the more primitive form. In the preparation of the fibre, the bark is thrown into a pot of boiling water, to which ashes have been added. After a few hours’ boiling, the bark is taken out and the fibre extracted.

(3) Tender shoots of bamboos eaten in the form of curry.

(4) Alternanthera sessilis. Pot-herbs.

Stellaria media.

Amarantus spinosus.

Amarantus polygonoides.

The following list of plants, of which the fruits are eaten by the Todas, has been brought together by Mr. K. Rangachari:—

Eugenia Arnottiana.—The dark purple juice of the fruit of this tree is used by Toda women for painting beauty spots on their faces.

Rubus ellipticus. Wild raspberry.

Rubus molucanus.

Rubus lasiocarpus.

Fragaria nilgerrensis, wild strawberry.

Elæagnus latifolia. Said by Dr. Mason to make excellent tarts and jellies.

Gaultheria fragrantissima.

Rhodomyrtus tomentosa, hill gooseberry.

Loranthus neelgherrensis. Parasitic on trees.

Loranthus loniceroides.

Elæocarpus oblongus.

Elæocarpus Munronii. Berberis aristata. Barberry.

Berberis nepalensis.

Solanum nigrum.

Vaccinium Leschenaultii.

Vaccinium nilgherrense.

Toddalia aculeata.

Ceropegia pusilla.

To which may be added mushrooms.

A list containing the botanical and Toda names of trees, shrubs, etc., used by the Todas in their ordinary life, or in their ceremonial, is given by Dr. Rivers.

Fire is, in these advanced days, obtained by the Todas in their dwelling huts for domestic purposes from matches. The men who came to be operated on with my measuring instruments had no hesitation in asking for a match, and lighting the cheroots which were distributed amongst them, before they left the Paikāra bungalow dining-room. Within the precincts of the dairy temple the use of matches is forbidden, and fire is kindled with the aid of two dry sticks of Litsæa Wightiana. Of these one, terminating in a blunt convex extremity, is about 2′ 3″ long; the other, with a hemispherical cavity scooped out close to one end, about 2½″ in length. A little nick or slot is cut on the edge of the shorter stick, and connected with the hole in which the spindle stick is made to revolve. “In this slot the dust collects, and, remaining in an undisturbed heap, seemingly acts as a muffle to retain the friction-heat until it reaches a sufficiently high temperature, when the wood-powder becomes incandescent.” Into the cavity in the short stick the end of the longer stick fits, so as to allow of easy play.

The smaller stick is placed on the ground, and held tight by firm pressure of the great toe, applied to the end furthest from the cavity, into which a little finely powdered charcoal is inserted. The larger stick is then twisted vigorously, “like a chocolate muller” (Tylor) between the palms of the hands by two men, turn and turn about, until the charcoal begins to glow. Fire, thus made, is said to be used at the sacred dairy (ti), the dairy houses of ordinary mands, and at the cremation of males. In an account of a Toda green funeral, Mr. Walhouse notes that “when the pile was completed, fire was obtained by rubbing two dry sticks together. This was done mysteriously and apart, for such a mode of obtaining fire is looked upon as something secret and sacred.”

At the funeral of a female, I provided a box of tändstickors for lighting the pyre. A fire-stick, which was in current use in a dairy, was polluted and rendered useless by the touch of my Brāhman assistant! It is recorded by Harkness that a Brāhman was not only refused admission to a Toda dairy, but actually driven away by some boys, who rushed out of it when they heard him approach. It is noted by Dr. Rivers that “several kinds of wood are used for the fire-sticks, the Toda names of these being kiaz or keadj (Litsæa Wightiana), mōrs (Michelia Nilagirica), parskuti (Elæagnus latifolia), and main (Cinnamomum Wightii).” He states further that, “whenever fire is made for a sacred purpose, the fire-sticks must be of the wood which the Todas call kiaz or keadj, except in the tesherot ceremony (qualifying ceremony for the office of palol) in which the wood of muli is used. At the niroditi ceremony (ordination ceremony of a dairyman), “the assistant makes fire by friction, and lights a fire of mulli wood, at which the candidate warms himself.” It is also recorded by Dr. Rivers that “in some Toda villages, a stone is kept, called tutmûkal, which was used at one time for making fire by striking it with a piece of iron.”

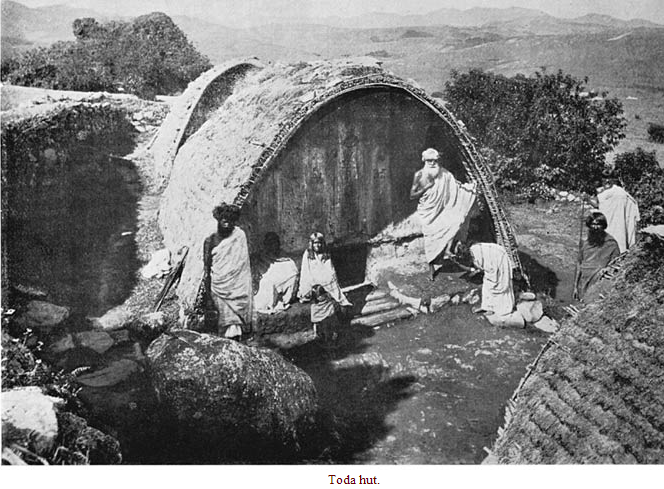

The abode of the Todas is called a mad or mand (village or hamlet), which is composed of huts, dairy temple, and cattle-pen, and has been so well described by Dr. Shortt, that I cannot do better than quote his account. “Each mand,” he says, “usually comprises about five buildings or huts, three of which are used as dwellings, one as a dairy, and the other for sheltering the calves at night. These huts form a peculiar kind of oval pent-shaped [half-barrel-shaped] construction, usually 10 feet high, 18 feet long, and 9 feet broad. The entrance or doorway measures 32 inches in height and 18 inches in width, and is not provided with any door or gate; but the entrance is closed by means of a solid slab or plank of wood from 4 to 6 inches thick and of sufficient dimensions to entirely block up the entrance. This sliding door is inside the hut, and so arranged and fixed on two stout stakes buried in the earth, and standing to the height of 2½ to 3 feet, as to be easily moved to and fro.

There are no other openings or outlets of any kind, either for the escape of smoke, or for the free ingress and egress of atmospheric air. The doorway itself is of such small dimensions that, to effect an entrance, one has to go down on all fours, and even then much wriggling is necessary before an entrance is effected. The houses are neat in appearance, and are built of bamboos closely laid together, fastened with rattan, and covered with thatch, which renders them water-tight. Each building has an end walling before and behind, composed of solid blocks of wood, and the sides are covered in by the pent-roofing, which slopes down to the ground. The front wall or planking contains the entrance or doorway. The inside of a hut is from 8 to 15 feet square, and is sufficiently high in the middle to admit of a tall man moving about with comfort. On one side there is a raised platform or pial formed of clay, about two feet high, and covered with sāmbar (deer) or buffalo skins, or sometimes with a mat. This platform is used as a sleeping place. On the opposite side is a fire place, and a slight elevation, on which the cooking utensils are placed. In this part of the building, faggots of firewood are seen piled up from floor to roof, and secured in their place by loops of rattan.

Here also the rice-pounder or pestle is fixed. The mortar is formed by a hole dug in the ground, 7 to 9 inches deep, and hardened by constant use. The other household goods consist of three or four brass dishes or plates, several bamboo measures, and sometimes a hatchet. Each hut or dwelling is surrounded by an enclosure or wall formed of loose stones piled up two or three feet high [with openings too narrow to permit of a buffalo entering through it]. The dairy is sometimes a building slightly larger than the others, and usually contains two compartments separated by a centre planking. One part of the dairy is a store-house for ghee, milk and curds, contained in separate vessels. The outer apartment forms the dwelling place of the dairy priest. The doorways of the dairy are smaller than those of the dwelling huts. The flooring of the dairy is level, and at one end there is a fire-place. Two or three milk pails or pots are all that it usually contains. The dairy is usually situated at some little distance from the habitations. The huts where the calves are kept are simple buildings, somewhat like the dwelling huts. In the vicinity of the mands are the cattle-pens or tuels[tu], which are circular enclosures surrounded by a loose stone wall, with a single entrance guarded by powerful stakes. In these, the herds of buffaloes are kept at night.

Each mand possesses a herd of these animals.” It is noted by Dr. Rivers that “in the immediate neighbourhood of a village there are usually well-worn paths, by which the village is approached, and some of these paths or kalvol receive special names. Some may not be traversed by women. Within the village there are also certain recognised paths, of which two are specially important. One, the punetkalvol, is the path by which the dairy man goes from his dairy to milk or tend the buffaloes; the other is the majvatitthkalvol, the path which the women must use when going to the dairy to receive butter-milk (maj) from the dairy man. Women are not allowed to go to the dairy or to other places connected with it, except at appointed times, when they receive buttermilk.”

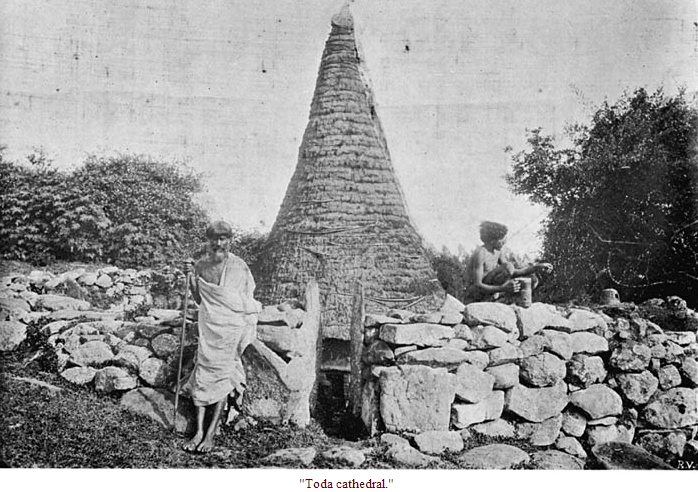

In addition to the dairies which in form resemble the dwelling-huts, the Todas keep up as dairy-temples certain curious conical edifices, of which there are said to be four on the Nīlgiri plateau, viz., at the Muttanād mand, near Kotagiri, near Sholūr, and at Mudimand. The last was out of repair a few years ago, but was, I was informed, going to be rebuilt shortly. It is suggested by Dr. Rivers as probable that in many cases a dairy, originally of the conical form, has been rebuilt in the same form as the dwelling-hut, owing to the difficulty and extra labour of reconstruction in the older shape. The edifice at the Muttanād mand (or Nōdrs), at the top of the Sīgūr ghāt, is known to members of the Ootacamund Hunt as the Toda cathedral. It has a circular stone base and a tall conical thatched roof crowned with a large flat stone, and is surrounded by a circular stone wall.

To penetrate within the sacred edifice was forbidden, but we were informed that it contained milking vessels, dairy apparatus, and a swāmi in the guise of a copper bell (mani). The dairyman is known as the varzhal or wursol. In front of the cattle-pen of the neighbouring mand, I noticed a grass-covered mound, which, I was told, is sacred. The mound contains nothing buried within it, but the bodies of the dead are placed near it, and earth from the mound is placed on the corpse before it is removed to the burning-ground. At “dry funerals” the buffalo is said to be slain near the mound. It has been suggested by Colonel Marshall that the “boa or boath [poh.] is not a true Toda building, but may be the bethel of some tribe contemporaneous with, and cognate to the Todas, which, taking refuge, like them, on these hills, died out in their presence.”

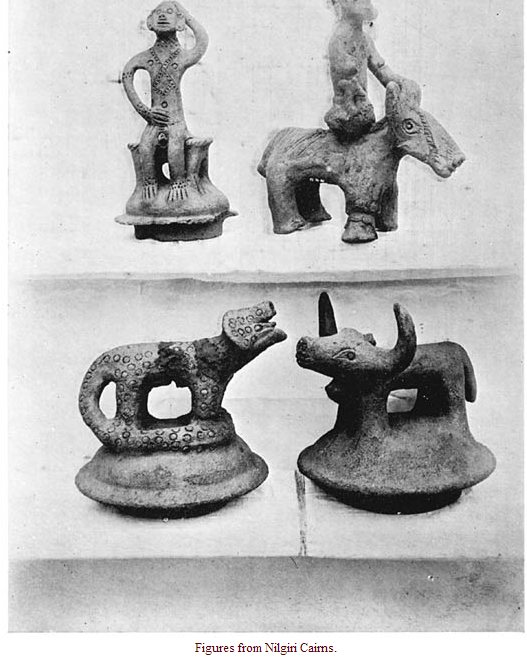

Despite the hypothesis of Dr. Rivers that the Todas are derived from one or more of the races of Malabar, their origin is buried among the secrets of the past. So too is the history of the ancient builders of cairns and barrows on the Nīlgiri plateau, which were explored by Mr. Breeks when Commissioner of the Nīlgiris. The bulk of the Breeks’ collection is now preserved in the Madras Museum, and includes a large series of articles in pottery, quite unlike anything known from other parts of Southern India. Concerning this series, Mr. R. Bruce Foote writes as follows.

“The most striking objects are tall jars, many-storied cylinders, of varying diameter with round or conical bases, fashioned to rest upon pottery ring-stands, or to be stuck into soft soil, like the amphoræ of classical times. These jars were surmounted by domed lids. On these lids stood or sat figures of the most varied kind of men, or animals, much more rarely of inanimate objects, but all modelled in the rudest and most grotesque style. Grotesque and downright ugly as are these figures, yet those representing men and women are extremely interesting from the light they throw upon the stage of civilization their makers had attained to, for they illustrate the fashion of the garments as also of the ornaments they wore, and of the arms or implements carried by them. The animals they had domesticated, those they chased, and others that they probably worshipped, are all indicated. Many figures of their domestic animals, especially their buffaloes and sheep, are decorated with garlands and bells, and show much ornamentation, which seems to indicate that they were painted over, a custom which yet prevails in many parts.” Among the most interesting figures are those of heavily bearded men riding on horses, and big-horned buffaloes which might have been modelled from the Toda buffaloes of to-day, and, like these, at funerals and migration ceremonies, bear a bell round the neck.

Two forms of Toda dairy have so far been noticed. But there remains a third kind, called the ti mand, concerning which Dr. Rivers writes as follows. “The ti is the name of an institution, which comprises a herd of buffaloes, with a number of dairies and grazing districts, tended by a dairy-man priest called palol, with an assistant called kaltmokh. Each dairy, with its accompanying buildings and pasturage, is called a ti mad, or ti village. The buffaloes belonging to a ti are of two kinds, distinguished as persiner and punir. The former are the sacred buffaloes, and the elaborate ceremonial of the ti dairy is concerned with their milk. The punir correspond in some respects to the putiir of the ordinary village dairy, and their milk and its products are largely for the personal use and profit of the palol, and are not treated with any special ceremony. During the whole time he holds office, the palol may not visit his home or any other ordinary village, though he may visit another ti village.

Any business with the outside world is done either through the kaltmokh, or with people who come to visit him at the ti. If the palol has to cross a river, he may not pass by a bridge, but must use a ford, and it appears that he may only use certain fords. The palol must be celibate, and, if married, he must leave his wife, who is in most cases also the wife of his brother or brothers.” I visited the ti mand near Paikāra by appointment, and, on arrival near the mand, found the two palols, well-built men aged about thirty and fifty, clad in black cloths, and two kaltmokhs, youths aged about eight and ten, naked save for a loin-cloth, seated on the ground, awaiting our arrival. As a mark of respect to the palols, the three Todas who accompanied me arranged their putkūlis so that the right arm was laid bare, and one of them, who was wearing a turban, removed it. A long palaver ensued in consequence of the palols demanding ten rupees to cover the expenses of the purificatory ceremonies, which, they maintained, would be necessary if I desecrated the mand by photographing it. Eventually, however, under promise of a far smaller sum, the dwelling-hut was photographed, with palols, kaltmokhs, and a domestic cat seated in front of it.

In connection with the palol being forbidden to cross a river by a bridge, it may be noted that the river which flows past the Paikāra bungalow is regarded as sacred by the Todas, and, for fear of mishap from arousing the wrath of the river god, a pregnant Toda woman will not venture to cross it. The Todas will not use the river water for any purpose, and they do not touch it unless they have to ford it. They then walk through it, and, on reaching the opposite bank, bow their heads. Even when they walk over the Paikāra bridge, they take their hand out of the putkūli as a mark of respect. Concerning the origin of the Paikāra river, a grotesque legend was narrated to us.

Many years ago, the story goes, two Todas, uncle and nephew, went out to gather honey. After walking for a few miles they separated, and proceeded in different directions. The uncle was unsuccessful in the search, but the more fortunate nephew secured two kandis (bamboo measures) of honey. This, with a view to keeping it all for himself, he secreted in a crevice among the rocks, with the exception of a very small quantity, which he made his uncle believe was the entire product of his search. On the following day, the nephew went alone to the spot where the honey was hidden, and found, to his disappointment, that the honey was leaking through the bottom of the bamboo measures, which were transformed into two snakes. Terrified at the sight thereof, he ran away, but the snakes pursued him (may be they were hamadryads, which have the reputation of pursuing human beings). After running a few minutes, he espied a hare (Lepus nigricollis) running across his course, and, by a skilful manœuvre, threw his body-cloth over it. Mistaking it for a man, the snakes followed in pursuit of the hare, which, being very fleet of foot, managed to reach the sun, which became obscured by the hoods of the reptiles. This fully accounts for the solar eclipse. The honey, which leaked out of the vessels, became converted into the Paikāra river.

In connection with the migrations of the herds of buffaloes, Dr. Rivers writes as follows. “At certain seasons of the year, it is customary that the buffaloes both of the village and the ti should migrate from one place to another. Sometimes the village buffaloes are accompanied by all the inhabitants of the village; sometimes the buffaloes are only accompanied by their dairy-man and one or more male assistants. There are two chief reasons for these movements of the buffaloes, of which the most urgent is the necessity for new grazing-places.... The other chief reason for the migrations is that certain villages and dairies, formerly important and still sacred, are visited for ceremonial purposes, or out of respect to ancient custom.” For the following note on a buffalo migration which he came across, I am indebted to Mr. H. C. Wilson. “During the annual migration of buffaloes to the Kundahs, and when they were approaching the bridle-path leading from Avalanchē to Sispāra, I witnessed an interesting custom.

The Toda family had come to a halt on the far side of the path; the females seated themselves on the grass, and awaited the passing of the sacred herd. This herd, which had travelled by a recognised route across country, has to cross the bridle-path some two or three hundred yards above the Avalanchē-Sispāra sign-post. Both the ordinary and sacred herd were on the move together. The former passed up the Sispāra path, while the latter crossed in a line, and proceeded slightly down the hill, eventually crossing the stream and up through the shōlas over the steep hills on the opposite side of the valley. As soon as the sacred herd had crossed the bridle-path, the Toda men, having put down all their household utensils, went to where the women and girls were sitting, and carried them, one by one, over the place where the buffaloes had passed, depositing them on the path above. One of the men told me that the females are not allowed to walk over the track covered by the sacred herd, and have to be carried whenever it is necessary to cross it. This herd has a recognised tract when migrating, and is led by the old buffaloes, who appear to know the exact way.”

The tenure under which lands are held by the Todas is summed up as follows by Mr. R. S. Benson in his report on the revenue settlement of the Nilgiris, 1885. “The earliest settlers, and notably Mr. Sullivan, strongly advocated the claim of the Todas to the absolute proprietary right to the plateau [as lords of the soil]; but another school, led by Mr. Lushington, has strongly combated these views, and apparently regarded the Todas as merely occupiers under the ryotwari system in force generally in the Presidency. From the earliest times the Todas have received from the cultivating Badagas an offering or tribute, called gudu or basket of grain, partly in compensation for the land taken up by the latter for cultivation, and so rendered unfit for grazing purposes, but chiefly as an offering to secure the favour, or avert the displeasure of the Todas, who, like the Kurumbas (q.v.), are believed by the Badagas to have necromantic powers over their health and that of their herds. The European settlers also bought land in Ootacamund from them, and to this day the Government pays them the sum of Rs. 150 per mensem, as compensation for interference with the enjoyment of their pastoral rights in and about Ootacamund.

Their position was, however, always a matter of dispute, until it was finally laid down in the despatch of the Court of Directors, dated 21st January, 1843. It was then decided that the Todas possessed nothing more than a prescriptive right to enjoy the privilege of pasturing their herds, on payment of a small tax, on the State lands. The Court desired that they should be secured from interference by settlers in the enjoyment of their mands, and of their spots appropriated to religious rites. Accordingly pattas were issued, granting to each mand three bullahs (11.46 acres) of land. In 1863 Mr. Grant obtained permission to make a fresh allotment of nine bullahs (34.38 acres) to each mand on the express condition that the land should be used for pasturage only, and that no right to sell the land or the wood on it should be thereby conveyed. It may be added that the so-called Toda lands are now regarded as the inalienable common property of the Toda community, and unauthorised alienation is checked by the imposition of a penal rate of assessment (G.O., 18th April 1882). Up to the date of this order, however, alienations by sale or lease were of frequent occurrence. It remains to be seen whether the present orders and subordinate staff will be more adequate than those that went before to check the practices referred to.” With the view of protecting the Toda lands, Government took up the management of these lands in 1893, and framed rules, under the Forest Act, for their management, the rights of the Todas over them being in no way affected by the rules of which the following is an abstract:—

1. No person shall fell, girdle, mark, lop, uproot, or burn, or strip off the bark or leaves from, or otherwise damage any tree growing on the said lands, or remove the timber, or collect the natural produce of such trees or lands, or quarry or collect stone, lime, gravel, earth or manure upon such lands, or break up such lands for cultivation, or erect buildings of any description, or cattle kraals; and no person or persons, other than the Todas named in the patta concerned, shall graze cattle, sheep, or goats upon such lands, unless he is authorised so to do by the Collector of Nilgiris, or some person empowered by him.

2. The Collector may select any of the said lands to be placed under special fire protection.

3. No person shall hunt, beat for game, or shoot in such lands without a license from the Collector.

4. No person shall at any time set nets, traps, or snares for game on such lands.

5. All Todas in the Nilgiri district shall, in respect of their own patta lands, be exempt from the operation of the above rules, and shall be at liberty to graze their own buffaloes, to remove fuel and grass for their domestic requirements, and to collect honey or wax upon such lands. They shall likewise be entitled to, and shall receive free permits for building or repairing their mands and temples.

6. The Collector shall have power to issue annual permits for the cultivation of grass land only in Toda pattas by Todas themselves, free of charge, or otherwise as Government may, from time to time, direct; but no Toda shall be at liberty to permit any person, except a Toda, to cultivate, or assist in the cultivation of such lands.

In 1905, the Todas petitioned Government against the prohibition by the local Forest authorities of the burning of grass on the downs, issued on the ground of danger to the shōlas (wooded ravines or groves). This yearly burning of the grass was claimed by the Todas to improve it, and they maintained that their cattle were deteriorating for want of good fodder. Government ruled that the grass on the plateau has been burnt by the inhabitants at pleasure for many years without any appreciable damage to forest growth, and the practice should not be disturbed.

Concerning the social organisation of the Todas, Mr. Breeks states that they are “divided into two classes, which cannot intermarry, viz., Dêvalyâl and Tarserzhâl. The first class consists of Peiki class, corresponding in some respects to Brāhmans; the second of the four remaining classes the Pekkan, Kuttan, Kenna, and Todi. A Peiki woman may not go to the village of the Tarserzhâl, although the women of the latter may visit Peikis.” The class names given by Mr. Breeks were readily recognised by the Todas whom I interviewed, but they gave Tērthāl (comprising superior Peikis) and Tārthāl as the names of the divisions. They told me that, when a Tērthāl woman visits her friends at a Tārthāl mand, she is not allowed to enter the mand, but must stop at a distance from it. Todas as a rule cook their rice in butter-milk, but, when a Tērthāl woman pays a visit to Tarthāl mand, rice is cooked for her in water. When a Tarthāl woman visits at a Tērthāl mand, she is permitted to enter into the mand, and food is cooked for her in buttermilk. The restrictions which are imposed on Tērthāl women are said to be due to the fact that on one occasion a Tērthāl woman, on a visit at a Tarthāl mand, folded up a cloth, and placed it under her putkūli as if it was a baby.

When food was served, she asked for some for the child, and on receiving it, exhibited the cloth. The Tarthāls, not appreciating the mild joke, accordingly agreed to degrade all Tērthāl women. According to Dr. Rivers, “the fundamental feature of the social organisation is the division of the community into two perfectly distinct groups, the Tartharol and the Teivaliol [=Dêvalyâl of Breeks]. There is a certain amount of specialisation of function, certain grades of the priesthood being filled only by members of the Teivaliol. The Tartharol and Teivaliol are two endogamous divisions of the Toda people. Each of these primary divisions is sub-divided into a number of secondary divisions [clans]. These are exogamous. Each class possesses a group of villages, and takes its name from the chief of these villages, Etudmad. The Tartharol are divided into twelve clans, the Teivaliol into six clans or madol.”

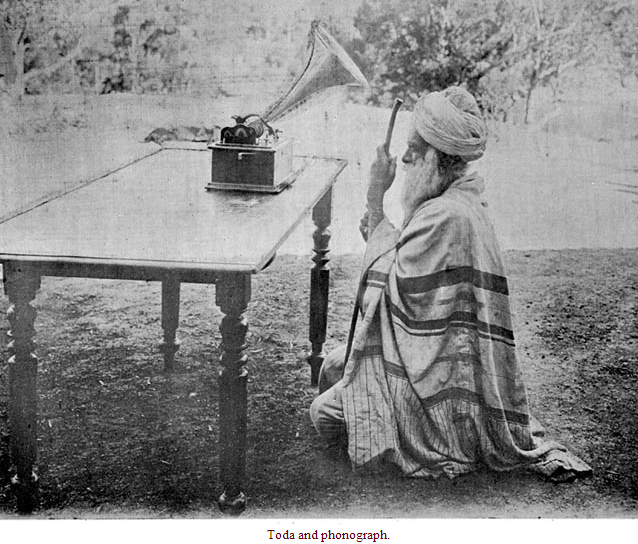

When a girl has reached the age of puberty, she goes through an initiatory ceremony, in which a Toda man of strong physique takes part. One of these splendid specimens of human muscularity was introduced to me on the occasion of a phonograph recital at the Paikāra bungalow.

Concerning the system of polyandry as carried out by the Todas, Dr. Rivers writes as follows. “The Todas have long been noted as a polyandrous people, and the institution of polyandry is still in full working order among them. When the girl becomes the wife of a boy, it is usually understood that she becomes also the wife of his brothers. In nearly every case at the present time, and in recent generations, the husbands of a woman are own brothers. In a few cases, though not brothers, they are of the same clan. Very rarely do they belong to different clans. One of the most interesting features of Toda polyandry is the method by which it is arranged who shall be regarded as the father of a child. For all social and legal purposes, the father of a child is the man who performs a certain ceremony about the seventh month of pregnancy, in which an imitation bow and arrow are given to the woman. When the husbands are own brothers, the eldest brother usually gives the bow and arrow, and is the father of the child, though, so long as the brothers live together, the other brothers are also regarded as fathers.

It is in the cases in which the husbands are not own brothers that the ceremony becomes of real social importance. In these cases, it is arranged that one of the husbands shall give the bow and arrow, and this man is the father, not only of the child born shortly afterwards, but also of all succeeding children, till another husband performs the essential ceremony. Fatherhood is determined so essentially by this ceremony that a man who has been dead for several years is regarded as the father of any children born by his widow, if no other man has given the bow and arrow. There is no doubt that, in former times, the polyandry of the Todas was associated with female infanticide, and it is probable that the latter custom still exists to some extent, though strenuously denied. There is reason to believe that women are now more plentiful than formerly, though they are still in a distinct minority. Any increase, however, in the number of women does not appear to have led to any great diminution of polyandrous marriages, but polyandry is often combined with polygyny. Two or more brothers may have two or more wives in common. In such marriages, however, it seems to be a growing custom that one brother should give the bow and arrow to one wife, and another brother to another wife.”

The pregnancy ceremony referred to above is called pursutpimi, or bow (and arrow) we touch. According to the account given to me by several independent witnesses, the woman proceeds, accompanied by members of the tribe, on a new moon-day in the fifth or seventh month of her pregnancy, to a shola, where she sits with the man who is to become the father of her child near a kiaz tree (Eugenia Arnottiana). The man asks the father of the woman if he may bring the bow, and, on obtaining his consent, goes in search of a shrub (Sophora glauca), from a twig of which he makes a mimic bow. The arrow is represented by a blade of grass called nark (Andropogon Schœnanthus).

Meanwhile a triangular niche has been cut in the kiaz tree, in which a lighted lamp is placed. The woman seats herself in front of the lamp, and, on the return of the man, asks thrice “Whose bow is it?” or “What is it?” meaning to whom, or to which mand does the child belong? The bow and arrow are handed to the woman, who raises them to her head, touches her forehead with them, and places them near the tree. From this moment the lawful father of the child is the man from whom she has received the bow and arrow. He places on the ground at the foot of the tree some rice, various kinds of grain, chillies, jaggery (crude sugar), and salt tied in a cloth. All those present then leave, except the man and woman, who remain near the tree till about six o’clock in the evening, when they return to the mand. The time is determined, in the vicinity of Ootacamund, by the opening of the flowers of Onothera tetraptera (evening primrose), a garden escape called by the Todas āru mani pūv (six o’clock flower), which opens towards evening. It may be noted that, at the second funeral of a male, a miniature bow and three arrows are burnt with various other articles within the stone circle (azaram).

A few years ago (1902), the Todas, in a petition to Government, prayed for special legislation to legalise their marriages on the lines of the Malabar Marriage Act. The Government was of opinion that legislation was unnecessary, and that it was open to such of the Todas as were willing to sign the declaration prescribed by section 10 of the Marriage Act III of 1872 to contract legal marriages under the provision of that Act. The Treasury Deputy Collector of the Nīlgiris was appointed Registrar of Toda marriages. No marriage has been registered up to the present time. The practice of infanticide among the Todas is best summed up in the words of an aged Toda during an interview with Colonel Marshall. “I was a little boy when Mr. Sullivan (the first English pioneer of the Nilgiris) visited these mountains. In those days it was the custom to kill children, but the practice has long died out, and now one never hears of it. I don’t know whether it was wrong or not to kill them, but we were very poor, and could not support our children. Now every one has a mantle (putkuli), but formerly there was only one for the whole family. We did not kill them to please any god, but because it was our custom. The mother never nursed the child, and the parents did not kill it. Do you think we could kill it ourselves? Those tell lies who say we laid it down before the opening of the buffalo-pen, so that it might be run over and killed by the animals.

We never did such things, and it is all nonsense that we drowned it in buffalo’s milk. Boys were never killed—only girls; not those who were sickly and deformed—that would be a sin; but, when we had one girl, or in some families two girls, those that followed were killed. An old woman (kelachi) used to take the child immediately it was born, and close its nostrils, ears, and mouth with a cloth thus—here pantomimic action. It would shortly droop its head, and go to sleep. We then buried it in the ground. The kelachi got a present of four annas for the deed.” The old man’s remark about the cattle-pen refers to the Malagasy custom of placing a new-born child at the entrance to a cattle-pen, and then driving the cattle over it, to see whether they would trample on it or not. The Missionary Metz bears out the statement that the Toda babies were killed by suffocation.

At the census, 1901, 453 male and 354 female Todas were returned. In a note on the proportion of the sexes among the Todas, Mr. R. C. Punnett states that “all who have studied the Todas are agreed upon the frequency of the practice (of infanticide) in earlier times. Marshall, writing in 1872, refers to the large amount of female infanticide in former years, but expresses his conviction that the practice had by that time died out. Marshall’s evidence is that of native assurance only. Dr. Rivers, who received the same assurance, is disinclined to place much confidence in native veracity with reference to this point, and, in view of the lack of encouragement which the practice receives from the Indian Government, this is not altogether surprising. The supposition of female infanticide, by accounting for the great disproportion in the numbers of the sexes, brings the Todas into harmony with what is known of the rest of mankind.” In summarising his conclusions, Mr. Punnett notes that:—

(1) Among the Todas, males predominate greatly over females.

(2) This preponderance is doubtless due to the practice of female infanticide, which is probably still to some extent prevalent.

(3) The numerical preponderance of the males has been steadily sinking during recent years, owing probably to the check which foreign intercourse has imposed upon female infanticide.

In connection with the death ceremonies of the Todas, Dr. Rivers notes that “soon after death the body is burnt, and the general name for the ceremony on this occasion is etvainolkedr, the first day funeral. After an interval, which may vary greatly in length, a second ceremony is performed, connected with certain relics of the deceased which have been preserved from the first occasion. The Toda name for this second funeral ceremony is marvainolkedr, the second day funeral, or ‘again which day funeral.’ The funeral ceremonies are open to all, and visitors are often invited by the Todas. In consequence, the funeral rites are better known, and have been more frequently described than any other features of Toda ceremonial. Like nearly every institution of the Todas, however, they have become known to Europeans under their Badaga names. The first funeral is called by the Badagas hase kedu, the fresh or green funeral, and the term ‘green funeral’ has not only become the generally recognised name among the European inhabitants of the Nilgiri hills, but has been widely adopted in anthropological literature. The second funeral is called by the Badagas bara kedu, the ‘dry funeral,’ and this term also has been generally adopted.”

The various forms of the funeral ceremonies are discussed in detail by Dr. Rivers, and it must suffice to describe those at which we have been present as eye-witnesses.

I had the opportunity of witnessing the second funeral of a woman who had died from smallpox two months previously. On arrival at a mand on the open downs about five miles from Ootacamund, we were conducted by a Toda guide to the margin of a dense shola, where we found two groups seated apart, consisting of (a) women, girls, and brown-haired female babies, round a camp fire; (b) men, boys, and male babies, carried, with marked signs of paternal affection, by their fathers. In a few minutes a murmuring sound commenced in the centre of the female group. Working themselves up to the necessary pitch, some of the women (near relatives of the deceased) commenced to cry freely, and the wailing and lachrymation gradually spread round the circle, until all, except little girls and babies who were too young to be affected, were weeping and mourning, some for fashion, others from genuine grief. In carrying out the orthodox form of mourning, the women first had a good cry to themselves, and then, as their emotions became more intense, went round the circle, selecting partners with whom to share companionship in grief. Gradually the group resolved itself into couplets of mourners, each pair with their heads in contact, and giving expression to their emotions in unison. Before separating to select a new partner, each couple saluted by bowing the head, and raising thereto the feet of the other, covered by the putkūli. [I have seen women rapidly recover from the outward manifestations of grief, and clamour for money.]

From time to time the company of mourners was reinforced by late arrivals from distant mands, and, as each detachment, now of men and now of women, came in view across the open downs, one could not fail to be reminded of the gathering of the clans on some Highland moor. The resemblance was heightened by the distant sound as of pipers, produced by the Kota band (with two police constables in attendance), composed of four Kotas, who made a weird noise with drums and flutes as they drew near the scene of action. The band, on arrival, took up a position close to the mourning women. As each detachment arrived, the women, recognising their relatives, came forward and saluted them in the manner customary among Todas by falling at their feet, and placing first the right and then the left foot on their head. Shortly after the arrival of the band, signals were exchanged, by waving of putkūlis, between the assembled throng and a small detachment of men some distance off. A general move was made, and an impromptu procession formed, with men in front, band in the middle, and women bringing up the rear. A halt was made opposite a narrow gap leading into the shola; men and women sat apart as before; and the band walked round, discoursing unsweet music.

A party of girls went off to bring fire from the spot just vacated for use in the coming ceremonial, but recourse was finally had to a box of matches lent by one of our party. At this stage we noticed a woman go up to the eldest son of the deceased, who was seated apart from the other men, and would not be comforted in spite of her efforts to console him. On receipt of a summons from within the shola, the assembled Toda men and ourselves swarmed into it by a narrow track leading to a small clear space round a big tree, from a hole cut at the base of which an elderly Toda produced a piece of the skull of the dead woman, wrapped round with long tresses of her hair. It now became the men’s turn to exhibit active signs of grief, and all of one accord commenced to weep and mourn. Amid the scene of lamentation, the hair was slowly unwrapt from off the skull, and burned in an iron ladle, from which a smell as of incense arose. A bamboo pot of ghī was produced, with which the skull was reverently anointed, and placed in a cloth spread on the ground. To this relic of the deceased the throng of men, amid a scene of wild excitement, made obeisance by kneeling down before it, and touching it with their foreheads.

The females were not permitted to witness this stage of the proceedings, with the exception of one or two near relatives of the departed one, who supported themselves sobbing against the tree. The ceremonial concluded, the fragment of skull, wrapt in the cloth, was carried into the open, where, as men and boys had previously done, women and girls made obeisance to it. A procession was then again formed, and marched on until a place was reached, where were two stone-walled kraals, large and small. Around the former the men, and within the latter the women, took up their position, the men engaging in chit-chat, and the women in mourning, which after a time ceased, and they too engaged in conversation. A party of men, carrying the skull, still in the cloth, set out for a neighbouring shola, where a kēdu of several other dead Todas was being celebrated; and a long pause ensued, broken eventually by the arrival of the other funeral party, the men advancing in several lines, with arms linked, and crying out U, hah! U, hah, hah! in regular time. This party brought with it pieces of the skulls of a woman and two men, which were placed, wrapt in cloths, on the ground, saluted, and mourned over by the assembled multitude. At this stage a small party of Kotas arrived, and took up their position on a neighbouring hill, waiting, vulture-like, for the carcase of the buffalo which was shortly to be slain.

Several young men now went off across the hill in search of buffaloes, and speedily re-appeared, driving five buffaloes before them with sticks. As soon as the beasts approached a swampy marsh at the foot of the hill on which the expectant crowd of men was gathered together, two young men of athletic build, throwing off their putkūlis, made a rush down the hill, and tried to seize one of the buffaloes by the horns, with the result that one of them was promptly thrown. The buffalo escaping, one of the remaining four was quickly caught by the horns, and, with arms interlocked, the men brought it down on its knees, amid a general scuffle. In spite of marked objection and strenuous resistance on the part of the animal—a barren cow—it was, by means of sticks freely applied, slowly dragged up the hill, preceded by the Kota band, and with a Toda youth pulling at its tail. Arrived at the open space between the kraals, the buffalo, by this time thoroughly exasperated, and with blood pouring from its nostrils, had a cloth put on its back, and was despatched by a blow on the poll with an axe deftly wielded by a young and muscular man. On this occasion no one was badly hurt by the sacrificial cow, though one man was seen washing his legs in the swamp after the preliminary struggle with the beast. But Colonel Ross-King narrates how he saw a man receive a dangerous wound in the neck from a thrust of the horn, which ripped open a wide gash from the collar-bone to the ear. With the death of the buffalo, the last scene, which terminated the strange rites, commenced; men, women, and children pressing forward and jostling one another in their eagerness to salute the dead beast by placing their hands between its horns, and weeping and mourning in pairs; the facial expression of grief being mimicked when tears refused to flow spontaneously.

The ceremonial connected with the final burning of the relics and burial of the ashes at the stone circle (azaram) are described in detail by Dr. Rivers.

A few days after the ceremony just described, I was invited to be present at the funeral of a young girl who had died of smallpox five days previously. I proceeded accordingly to the scene of the recent ceremony, and there, in company with a small gathering of Todas from the neighbouring mands, awaited the arrival of the funeral cortége, the approach of which was announced by the advancing strains of Kota music. Slowly the procession came over the brow of the hill; the corpse, covered by a cloth, on a rude ladder-like bier, borne on the shoulders of four men, followed by two Kota musicians; the mother carried hidden within a sack; relatives and men carrying bags of rice and jaggery, and bundles of wood of the kiaz tree (Eugenia Arnottiana) for the funeral pyre. Arrived opposite a small hut, which had been specially built for the ceremonial, the corpse was removed from the bier, laid on the ground, face upwards, outside the hut, and saluted by men, women, and children, with the same manifestations of grief as on the previous occasion. Soon the men moved away to a short distance, and engaged in quiet conversation,

leaving the females to continue mourning round the corpse, interrupted from time to time by the arrival of detachments from distant mands, whose first duty was to salute the dead body. Meanwhile a near female relative of the dead child was busily engaged inside the hut, collecting together in a basket small measures of rice, jaggery, sago, honey-comb, and the girl’s simple toys, which were subsequently to be burned with the corpse. The mourning ceasing after a time, the corpse was placed inside the hut, and followed by the near relatives, who there continued to weep over it. A detachment of men and boys, who had set out in search of the buffaloes which were to be sacrificed, now returned driving before them three cows, which escaped from their pursuers to rejoin the main herd. A long pause ensued, and, after a very prolonged drive, three more cows were guided into a marshy swamp, where one of them was caught by the horns, and dragged reluctantly, but with little show of fight, to the strains of Kota drum and flute, in front of the hut, where it was promptly despatched by a blow on the poll. The corpse was now brought from within the hut, and placed, face upwards, with its feet resting on the forehead of the buffalo, whose neck was decorated with a silver chain, such as is worn by Todas round the loins, as no bell was available, and the horns were smeared with butter.

Then followed frantic manifestations of grief, amid which the unhappy mother fainted. Mourning over, the corpse was made to go through a form of ceremony, resembling that which is performed during pregnancy with the first child. A small boy, three years old, was selected from among the relatives of the dead girl, and taken by his father in search of a certain grass (Andropogon Schœnanthus) and a twig of a shrub Sophora glauca), which were brought to the spot where the corpse was lying. The mother of the dead child then withdrew one of its hands from the putkūli, and the boy placed the grass and twig in the hand, and limes, plantains, rice, jaggery, honey-comb, and butter in the pocket of the putkūli, which was then stitched with needle and thread in a circular pattern. The boy’s father then took off his son’s putkūli, and replaced it so as to cover him from head to foot. Thus covered, the boy remained outside the hut till the morning of the morrow, watched through the night by near relatives of himself and his dead bride. [On the occasion of the funeral of an unmarried lad, a girl is in like manner selected, covered with her putkūli from head to foot, and a metal vessel filled with jaggery, rice, etc., to be subsequently burnt on the funeral pyre, placed for a short time within the folds of the putkūli. Thus covered, the girl remains till next morning, watched through the dreary hours of the night by relatives. The same ceremony is performed over the corpse of a married woman who has not borne children, the husband acting as such for the last time, in the vain hope that the woman may produce issue in heaven.]

The corpse was borne away to the burning-ground within the shola, and, after removal of some of the hair by the mother of the newly wedded boy, burned, with face upwards, amid the music of the Kota band, the groans of the assembled crowd squatting on the ground, and the genuine grief of the nearest relatives. The burning concluded, a portion of the skull was removed from the ashes, and handed over to the recently made mother-in-law of the dead girl, and wrapped up with the hair in the bark of the tūd tree (Meliosma pungens). A second buffalo, which, properly speaking, should have been slain before the corpse was burnt, was then sacrificed, and rice and jaggery were distributed among the crowd, which dispersed, leaving behind the youthful widower and his custodians, who, after daybreak, partook of a meal of rice, and returned to their mands; the boy’s mother taking with her the skull and hair to her mand, where it would remain until the celebration of the second funeral. No attention is paid to the ashes after cremation, and they are left to be scattered by the winds.

A further opportunity offered itself to be present at the funeral of an elderly woman on the open downs not far from Paikāra, in connection with which certain details possess some interest. The corpse was, at the time of our arrival, laid out on a rude bier within an improvised arbour covered with leaves and open at each end, and tended by some of the female relatives. At some little distance, a conclave of Toda men, who rose of one accord to greet us, was squatting in a circle, among whom were many venerable white-turbaned elders of the tribe, protected from the scorching sun by palm-leaf umbrellas. Amid much joking, and speech-making by the veterans, it was decided that, as the eldest son of the deceased woman was dead, leaving a widow, this daughter-in-law should be united to the second son, and that they should live together as man and wife. On the announcement of the decision, the bridegroom-elect saluted the principal Todas present by placing his head on their feet, which were sometimes concealed within the ample folds of the putkūli. At the funeral of a married woman, three ceremonies must, I was told, be performed, if possible, by a daughter or daughter-in-law, viz.:—

(1) Tying a leafy branch of the tiviri shrub (Atylosia Candolleana) in the putkūli of the corpse;

(2) Tying balls of thread and cowry shells on the arm of the corpse, just above the elbow;

(3) Setting fire to the funeral pyre, which was, on the present occasion, done by lighting a rag fed with ghī with a match.

The buffalo capture took place amid the usual excitement, and with freedom from accident; and, later in the day, the stalwart buffalo catchers turned up at the travellers’ bungalow for a pourboire in return, as they said, for treating us to a good fight. The beasts selected for sacrifice were a full-grown cow and a young calf. As they were dragged near to the corpse, now removed from the arbour, butter was smeared over the horns, and a bell tied round the neck. The bell was subsequently removed by Kotas, in whose custody, it was said, it was to remain till the next day funeral. The death-blow, or rather series of blows, having been delivered with the butt end of an axe, the feet of the corpse were placed at the mouth of the buffalo. In the case of a male corpse, the right hand is made to clasp the horns. [It is recorded by Dr. Rivers that, at the funeral of a male, men dance after the buffalo is killed. In the dancing a tall pole, called tadri or tadrsi, decorated with cowry shells, is used.]

The customary mourning in couples concluded, the corpse, clad in four cloths, was carried on the stretcher to a clear space in the neighbouring shola, and placed by the side of the funeral pyre, which had been rapidly piled up. The innermost cloth was black in colour, and similar to that worn by a palol. Next to it came a putkūli decorated with blue and red embroidery, outside which again was a plain white cloth covered over by a red cotton cloth of European manufacture. Seated by the side of the pyre, near to which I was courteously invited to take a seat on the stump of a rhododendron, was an elderly relative of the dead woman, who, while watching the ceremonial, was placidly engaged in the manufacture of a holly walking-stick with the aid of a glass scraper. The proceedings were watched on behalf of Government by a forest guard, and a police constable who, with marked affectation, held his handkerchief to his nose throughout the ceremonial. The corpse was decorated with brass rings, and within the putkūli were stowed jaggery, a scroll of paper adorned with cowry shells, snuff and tobacco, cocoanuts, biscuits, various kinds of grain, ghī, honey, and a tin-framed looking-glass.

A long purse, containing a silver Japanese yen and an Arcot rupee of the East India Company, was tied up in the putkūli close to the feet. These preliminaries concluded, the corpse was hoisted up, and swung three times over the now burning pyre, above which a mimic bier, made of slender twigs, was held. The body was then stripped of its jewelry, and a lock of hair cut off by the daughter-in-law for preservation, together with a fragment of the skull. I was told that, when the corpse is swung over the pyre, the dead person goes to amnodr (the world of the dead). In this connection, Dr. Rivers writes that “it would seem as if this ceremony of swinging the body over the fire was directly connected with the removal of the objects of value. The swinging over the fire would be symbolic of its destruction by fire; and this symbolic burning has the great advantage that the objects of value are not consumed, and are available for use another time. This is probably the real explanation of the ceremony, but it is not the explanation given by the Todas themselves. They say that long ago, about 400 years, a man supposed to be dead was put on the funeral pyre, and, revived by the heat, he was found to be alive, and was able to walk away from the funeral place.

In consequence of this, the rule was made that the body should always be swung three times over the fire before it is finally placed thereon.” [Colonel Marshall narrates the story that a Toda who had revived from what was thought his death-bed, has been observed parading about, very proud and distinguished looking, wearing the finery with which he had been bedecked for his own funeral, and which he would be permitted to carry till he really departed this life.] As soon as the pyre was fairly ablaze, the mourners, with the exception of some of the female relatives, left the shōla, and the men, congregating on the summit of a neighbouring hill, invoked their god. Four men, seized, apparently in imitation of the Kota Dēvādi, with divine frenzy, began to shiver and gesticulate wildly, while running blindly to and fro with closed eyes and shaking fists. They then began to talk in Malayālam, and offer an explanation of an extraordinary phenomenon, which had appeared in the form of a gigantic figure, which disappeared as suddenly as it appeared. At the annual ceremony of walking through fire (hot ashes) in that year, two factions arose owing to some dissension, and two sets of ashes were used. This seems to have annoyed the gods, and those concerned were threatened with speedy ruin. But the whole story was very vague. The possession by some Todas of a smattering of Malayālam is explained by the fact that, when grazing their buffaloes on the northern and western slopes of the Nīlgiris, they come in contact with Malayālam-speaking people from the neighbouring Malabar district.

At the funeral of a man (a leper), the corpse was placed in front of the entrance to a circle of loose stones about a yard and a half in diameter, which had been specially constructed for the occasion. Just before the buffalo sacrifice, a man of the Paiki clan standing near the head of the corpse, dug a hole in the ground with a cane, and asked a Kenna who was standing on the other side, “Puzhut, Kenna,” shall I throw the earth?—three times. To which the Kenna, answering, replied “Puzhut”—throw the earth—thrice. The Paiki then threw some earth three times over the corpse, and three times into the miniature kraal. It is suggested by Dr. Rivers that the circle was made to do duty for a buffalo pen, as the funeral was held at a place where there was no tu (pen), from the entrance of which earth could be dug up. Several examples of laments relating to the virtues and life of the deceased, which are sung or recited in the course of the funeral ceremonies, are given by Dr. Rivers. On the occasion of the reproduction of a lament in my phonograph, two young women were seen to be crying bitterly. The selection of the particular lament was unfortunate, as it had been sung at their father’s funeral. The reproduction of the recitation of a dead person’s sins at a Badaga funeral quickly restored them to a state of cheerfulness.

The following petition to the Collector of t

he Nilgiris on the subject of buffalo sacrifice may be quoted as a sign of the times, when the Todas employ petition-writers to express their grievances:—

“According to our religious custom for the long period, we are bringing forward of our killing buffaloes without any irregular way. But, in last year, when the late Collector came to see the said place, by that he ordered to the Todas first not to keep the buffaloes without feeding in the kraal, and second he ordered to kill each for every day, and to clear away the buffaloes, and not to keep the buffaloes without food. We did our work according to his orders, and this excellent order was an ample one. Now this ——, a chief of the Todas, son of ——, a deceased Toda, the above man joined with the moniagar of —— village, joined together, and, dealing with bribes, now they arose against us, and doing this great troubles on us, and also, by this great trouble, one day Mr. —— came for shooting snapes (snipe) by that side. By chance one grazing buffalo came to him, push him by his horns very forcely, and wounded him on his leg. By the help of another gentleman who came with him he escaped, or he would have die at the moment. Now the said moniagar and —— joined together, want to finish the funeral to his late father on the 18th instant. For this purpose they are going to shut the buffaloes without food in the kraal on the 18th instant at 10 o’clock. They are going to kill the buffaloes on the 19th instant at 4 o’clock in the evening. But this is a great sin against god. But we beg your honour this way. That is, let them leave the buffaloes in the grazing place, and ask them to catch and kill them at the same moment. And also your honour cannot ordered them to keep them in the kraal without food. And, if they will desire to kill the buffaloes in this way, these buffaloes will come on us, and also on the other peoples one who, coming to see funs on those day, will kill them all by his anxious. And so we the Todas begs your honour to enquire them before the 18th, the said funeral ceremony commencing, and not to grant the above orders to them.”

A Whit Monday at Paikāra was given up to an exhibition of sports and games, whereof the most exciting and interesting was a burlesque representation of a Toda funeral by boys and girls. A Toda, who was fond of his little joke, applied the term pacchai kēdu (green funeral) to the corpses of the flies entrapped by a viscous catch’em-alive-oh on the bungalow table. To the mock funeral rites arrived a party of youths, as from a distant mand, and crying out U, hah, in shrill mimicry of their elders. The lad who was to play the leading part of sacrificial buffalo, stripping off his putkūli, disappeared from sight over the brow of a low hillock. Above this eminence his bent and uplifted upper extremities shortly appeared as representatives of the buffalo horns. At sight thereof, there was a wild rush of small boys to catch him, and a mimic struggle took place, while the buffalo was dragged, amid good-tempered scuffling, kicks, and shouting, to the spot where the corpse should have been. This spot was, in the absence of a pseudo-dead body or stage dummy, indicated by a group of little girls, who had sat chatting together till the boy-beast arrived, when they touched foreheads, and went, with due solemnity, through the orthodox observance of mourning in couples. The buffalo was slain by a smart tap on the back of the head with a cloth, which did duty for an axe. As soon as the convulsive movements and twitchings of the death struggle were over, the buffalo, without waiting for an encore, retired behind the hillock once more, in order that the rough and tumble fight, which was evidently the chief charm of the game, might be repeated. The buffalo boy later on came in second in a flat race, and he was last seen protecting us from a mischievous-looking member of his herd, which was grazing on the main-road. Toda buffaloes, it may be noted, are not at all popular with members of the Ootacamund Hunt, as both horses and riders from time to time receive injuries from their horns, when they come in collision.

While the funeral game was in progress, the men showed off their prowess at a game (eln),52 corresponding to the English tip-cat, which is epidemic at a certain season in the London bye-streets. It is played with a bat like a broomstick, and a cylindrical piece of wood pointed at both ends. The latter is propped up against a stone, and struck with the bat. As it flies off the stone, it is hit to a distance with the bat, and caught (or missed) by the out fields. At the Muttanād mand, we were treated to a further exhibition of games. In one of these, called narthpimi, a flat slab of stone is supported horizontally on two other slabs fixed perpendicularly in the ground so as to form a narrow tunnel, through which a man can just manage to wriggle his body with difficulty. Two men take part in the game, one stationing himself at a distance of about thirty yards, the other about sixty yards from the tunnel. The front man, throwing off his mantle, runs as hard as he can to the tunnel, pursued by the ‘scratch’ man, whose object is to touch the other man’s feet before he has squeezed himself through the tunnel. Another sport, which we witnessed, consists of trial of strength with a heavy globular stone, the object being to raise it up to the shoulder; but a strong, well-built-man—he who was entrusted with slaying the funeral buffalo—failed to raise it higher than the pit of the stomach, though straining his muscles in the attempt. A splendidly made veteran assured me that, when young and lusty, he was able to accomplish the feat, and spoke sadly of degeneration in the physique of the younger members of the tribe. Mr. Breeks mentions that the Todas play a game resembling puss-in-the-corner, called kāriālapimi, which was not included in the programme of sports got up for our benefit. Dr. Rivers writes that “the Todas, and especially the children, often play with mimic representations of objects from practical life. Near the villages I have seen small artificial buffalo-pens and fireplaces made by the children in sport.” I have, on several occasions, come across young children playing with long and short pieces of twigs representing buffaloes and their calves, and going solemnly through the various incidents in the daily life of these animals. Todas, both old and young, may constantly be seen twisting flexible twigs into representations of buffaloes’ heads and horns.

Of Toda songs, the following have been collected:—

Sunshine is increasing. Mist is fast gathering. Rain may come. Thunder roars. Clouds are gathering.

Rain is pouring. Wind and rain have combined.

Oh, powerful god, may everything prosper!

May charity increase!

May the buffaloes become pregnant!

See that the buffaloes have calves.

Go and tell this to the god of the land.

Keygamor, Eygamor (names of buffaloes).

Evening is approaching. The buffaloes are coming.

The calves also have returned.

The buffaloes are saluted.

The dairy-man beats the calves with his stick.