Tirunelveli District

Contents |

Tinnevelly District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts.Many units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Tirunelveli

A District of the Madras Presidency which occupies the eastern half of the extreme southern end of the Indian peninsula. It lies between 8° 9' and 9° 43' N. and 77° 12' and 78° 23' E., and has an area of 5,389 square miles, with an extreme length of 120 miles from north to south and a maximum width of 75 miles near the Madura frontier. In shape it is roughly triangular, having the Western Ghats as its western and the sea as its eastern and southern boundary. On the north it is separated from Madura District by no natural features, but by a parallel drawn east and west through the town of Virudupatti.

Physical aspects

The southernmost hills of the Western Ghats serve as a natural barrier between the west side of the District and the State of Travancore up to within a few miles of Cape Comorin, the extreme southern point of the Indian peninsula. These hills vary from 3,000 to 5,000 feet in height and are clothed with heavy forest. Agastyamalai, half in Tinnevelly and half in Travancore, is their highest peak, rising to 6,200 feet; it was formerly an important astronomical station. Ma- hendragiri, another peak 14 miles from Nanguneri, 5,370 feet high, is reputed to be the hill from which the monkey-god Hanuman jumped across to Lanka (Ceylon) when he went to gather news of Sua, the wife of Rama, whom Ravana, the demon-king of Ceylon, had carried off.

From the base of the Ghats, where the country is nowhere higher than about 750 feet, the District slopes down eastward to the sea. Besides the Ghats, there is no range worth the name except the Vallanad hills in the Srivaikuntam taluk^ which rise abruptly from the surrounding plain to a height of over 1,000 feet and form a pleasing contrast to the level ground around them. Along the base of the Ghats is a belt from 10 to 20 miles wide of red loam and red sand, and fringing the sea is a strip of sandy soil from 3 to 15 miles in breadth. These two tracts widen out and overlap one another as they go south- ward, occupying the whole of the country to the south of Tinne- velly town. Between them, to the north, the intervening space is occupied by broad plains of black cotton soil.

All the rivers of the District have their sources in the Ghats and run eastwards to the sea. The Tambraparni, the most important of them, rises on the southern slope of the Agastyamalai peak and, after a south- easterly course of 70 miles, empties itself into the Gulf of Manaar. The Chittar, a much smaller stream, drains the mountains on the western border of the Tenkasi taluk and joins the Tambraparni a few miles north-east of Tinnevelly town. The Vaippar, which rises in the Sankaranayinarkovil hills, though a stream of considerable size, does not contribute much to the prosperity of the District, as its supply is too sudden and occasional to be of use in irrigation.

The geological basis of the District is a continuation of the gneiss rock of which the mountains on the west consist. In the plains this is largely covered by more recent formations, but protrudes through them in isolated patches or rounded and often conical masses, some of which supply excellent stone for building and road-making. Of the strata which overlie the gneiss rock, the principal are : first, a quartz, having a considerable percentage of iron, and appearing through the soil in the pale red ridges which are such conspicuous objects in all the tdhiks bordering the Ghats ; secondly, a kankar or nodular limestone underlying a poor stony soil, which is chiefly found in the central portion of the District : and, thirdly, sandstone alternating with clay- stone, which forms a coast series and follows the line of the shore at a distance of about 10 miles. This last originally formed a nearly con- tinuous ridge rising to about 300 feet, and through this the rivers descending from the Ghats have cut their way down to the sea. Round about it lie the teri tracts, the surface of which consists entirely of blown sand, and which form one of the most peculiar natural features of the District. In the north, the rock which underlies the plains is covered with a wide spread of black cotton soil, extending from the Madura boundary southward for about 60 miles and having an average breadth of 40 miles. Lastly, we have the river alluvium, which forms a narrow but extremely rich strip on either side of the Tambraparni and Chittar rivers.

The District comprises tracts of wide differences in rainfall and elevation, and its flora is consequently varied. Along the sea-shore are salt swamps and the red-sand wastes known locally as teris ; and the plants of these differ widely from those of the central plain, which resemble those in the rest of the similar tracts on the East Coast. The varying levels of the Ghats each have their own distinctive flora, the most interesting, perhaps, being the heavy evergreen forest. The characteristic tree of the plains is the palmyra palm, which covers wide areas to the exclusion of all other trees, and is a notable factor in the economic condition of the country.

On the plains of the District there is little in the way of large game, only antelope and occasional leopards being met with \ but on the Ghats occur the wild animals usual in heavy forest of high elevation. The Nilgiri ibex is found in several localities along this range.

The principal characteristics of the climate of Tinnevelly are light rainfall and an equable temperature. In the hot months, from March to June, the thermometer rarely rises above 95° in the shade ; in the coolest months, December and January, it seldom falls below 77*^. The mean temperature of Tinnevelly town is 85°, which is the highest figure in the Presidency. This unenviable position is, however, attained less by the heat of its hot months than by the absence of any really cold season. From June onwards, as long as the south- west monsoon lasts, the heat in the tracts lying at the foot of the Ghats is sensibly diminished by the winds and slight showers which find their way through the various gaps and passes in that range.

The rainfall is greatest near the hills and least on the eastern side of the District. In Tenkasi and Ambasamudram the maximum is nearly 60 inches, while the minimum is about 20 inches. In other parts of the District the fall varies from between 40 and 50 inches as a maximum to between 10 and 15 inches as a minimum. The average annual amount received in the District as a whole is about 25 inches, which is one of the lowest figures in the Presidency. But though its rainfall is scanty, Tinnevelly gets the benefit of the two monsoons, as both cause freshes in the Tambraparni. These, indeed, occasionally rise very high and do considerable damage.

History

Until the eighteenth century the history of Tinnevelly is almost identical with that of Madura District, sketched in the separate article on the latter. The capital of the first rulers of Madura, the Pandvas, is reputed to have been at one time within Tinnevelly District at Kolkai near the mouth of the Tambraparni. Tirumala Naik, the most famous of the Naik dynasty of Madura, built himself a small palace at Srivilliputtur in the north- west corner of the District.

In 1743, when the Nizam-ul-mulk, the Subahdar of the Deccan, expelled the Marathas from most of Southern India, Tinnevelly passed under the nominal rule of the Nawabs of Argot. All actual authority, however, lay in the hands of a number of independent military chiefs c'd\\(idi poligdrs^ originally feudal barons appointed by the Naik deputies who on the fall of that dynasty had assumed wider powers. They had forts in the hills and in the dense jungle with which the District was covered, maintained about 30,000 brave (though undisciplined) troops, and were continually fighting with each other or in revolt against the paramount power. A British expedition under Major Heron and Mahfuz Khan in 1755 reduced Tinnevelly to some sort of order, and ihe country was rented to the latter. He was, however, unable to control the poHgars, who formed themselves into a league for the conquest of Madura and advanced against him. 'i'hey were, however, signally defeated at a battle fought 7 miles north of Tinnevelly. But the utter failure of Mahfuz's government induced the Madras Government to Licnd an expedition under Muhammad Yusuf, their sepoy connnandant, to help him. This man eventually became renter of Tinnevelly, but rebelled in 1763 and was taken and hanged in the following year. Thenceforth the troops in Tinnevelly were commanded by British officers, while the country was administered, on behalf of the Nawab, by native officials. As this s)stem of divided responsibility was not conducive to the general pacification of the country, the Nawab was induced, in 1781, to assign the revenues to the East India Company, and civil officers, called Superintendents of Assigned Revenue, were appointed for its administration. The British, however, were at that time too busy with the wars with Haidar All to be able to pacify the country thoroughly, and the poligdrs continued to be troublesome. Encouraged by the Dutch, who had expelled the Portuguese from the Tinnevelly coast in 1658, obtained possession of the pearl fishery, and established a lucrative trade, they were soon again in open rebellion. In 1783 Colonel Fullarton reduced the stronghold at Panjalam- kurichi, near Ottappidaram, of Kattabomiiia Naik, the must fonnidable of them. In 1797 the poligdrs, headed by Kattabomma, again gave trouble, joining a rebeUion which broke out in the Ramnad territory. In 1799 Seringapatam fell and the Company's troops were at last free to move. A force was sent to Tinnevelly under Major Bannerman to compel obedience, and the first Poligar War followed. Panjalam- kurichi was taken, its poligar hanged, and the estates of his allies confiscated. Some of the poligars, notably the chief of Ettaiyapuram, helped the British. Two years later, some dangerous characters "who had been confined in the fort at Palamcottah broke loose and raised another rebellion. The operations which followed are known as the second Poligar War. Panjalamkurichi fell after a most stubborn resis- tance, the fort was destroyed, and the site of the place was ploughed over. The ringleaders of the rebellion were hanged, others who had assisted in it were transported, and the possession of arms was prohibited. In 1801 the Company assumed the government of the whole of the Carnatic under a treaty with the Nawab, making him a pecuniary allowance. Tinnevelly thus came absolutely into British hands, and from that date its history has been peaceful.

As the reputed seat of the earliest Dravidian civilization, Tinnevelly possesses much antiquarian interest. The most noteworthy archaeo- logical remains are the sepulchral urns found buried in the sides of the red gravel hills which abound in different parts of the District. Those at Adichanallur, 3 miles from Srivaikuntam, the most interesting pre- historic burial-place in all Southern India, are noticed in the separate article on that place. Kolkai and Kayal, near the mouth of the Tam- braparni, were the capitals of a later race, but nothing now remains to mark their ancient glory. Among the many temples in the District, those at Tiruchendur, Alvar Tirunagari, Srivaikuntam, Tinnevelly town, Nanguneri, Srivilliputtur, Tenkasi, Papanasam, Kalugumalai, and Kut- talam, deserve special mention. Ancient Roman coins are not uncommon in Tinnevelly, and those of the old Pandyan kings are numerous. Some Venetian gold ducats have also been unearthed in the District.

Population

The District contains 29 towns, or more than any other in the Presidency, and 1,482 villages. It is made up of the nine taluks of Ambasamudram, Nanguneri, Ottappidaram, San- karanavinarkovil, Sattur, Srivaikuntam, Srivil- liputtur, Tenkasi, and Tinnevelly, the head-quarters of which are at the places from which they are respectively named. Statistical particulars of these, according to the Census of 1901, will be found on the next page.

The population of the District in 1871 was 1,693,959; i" 1881, 1,699,747; in 1891, 1,916,095; and in 1901, 2,059,607. The last total was made up of 1,798,519 Hindu-s, 101,875 Mu.salnians, and 159,213 Christians. Between 187 1 and 1881, owing to the famine of 1876-8, the population was almost stationary. During tlie ne.xt ten years the rate of advance was probably slightly abnormal, owing to the usual rebound after scarcity ; and in the decade ending 1901 the increase was about equal to that in the Presidency as a whole. Emigration from the District was, however, considerable during that period. Few people move into it, and the proportion of the inhabitants who had been born within it was higher in 1901 than in any of the southern Districts. In density of population it is above the average for those Districts ; the Tinnevelly and Srivaikuntam taluks support nearly 600 persons per square mile. Between 1891 and 1901 the population of the Ambasamudram taluk declined, while that of the adjoining area of Nanguneri advanced abnormally. The reason for this was that in the former year the rice harvest in Ambasamudram, which always attracts coolies from Nanguneri, was being gathered at the time of the Census.

Tinnevelly contains more towns and a larger urban population than any other District in Madras. About 23 per cent, of the people live in towns, which is more than twice the proportion for the Presidency as a whole. These places, however, are not large cities. None of them contains more than 50,000 inhabitants, and only 5 out of the 29 possess more than 25,000. These are the four municipalities of Tinnevelly (population, 40,469), Palamcottah (39,545), the head-quarters of the District, Tuticorin (28,048), and Srivilliputtuk (26,382), and the large Union of Rajapalaiyam (25,360). Sixteen other Unions have a population of more than to,ooo each. The growth of these towns during the decade ending 1901 was remarkable. The popu- lation both of the municipalities and the Unions advanced in the aggre- gate by nearly one-half. In some cases the increase is partly due to the extension of the official limits of the towns to include suburbs; but such extensions would not have been made unless these suburbs had advanced in populousness and urban characteristics, and the statistics are therefore signs of real growth.

Tamil is the prevailing vernacular, being spoken by 86 per cent, of the total; but Telugu is the language of 13 per cent., being spoken by more than one-fifth of the inhabitants of the Ottappidaram and Srlvilliputtilr taluks and by nearly a third of those of Sattur.

The majority of the Musalmans of the District are Labbai traders. Christians are proportionately more numerous (8 per cent, of the total) than in any other Madras District, except the Nllgiris. They have, however, increased more slowly during the last twenty years than the population as a whole.

The great majority of the Hindus are Tamils. The three most numerous castes are the Shanans (294,000), the Pallans (234,000), and the Maravans (211,000), each of which are found in greater strength in Tinnevelly than in any other District. The first are really even more numerous than the figures show, as at the Census some thousands entered themselves as Kshattriyas, to which aristocratic body they have in recent years claimed to belong. There can be little doubt that, though large numbers of them now subsist by agriculture and trade, they originally followed the despised calling of toddy-drawing ; and in consequence of this the claims to be Kshattriyas and to enter Hindu temples which they have of late years put forward with nuu h tenacity caused great resentment among the other Hindus of the District, which finally culminated in the Tinnevelly riots of 1899 referred to below. Their chief opponents in these disturbances were the Maravans, a community of cultivators practically confined to Madura and Tinnevelly, who have a reputation for truculence. With the Kalians they gave much trouble during the Poligar Wars, and they still have an unenviable name for their expertness in dacoity and cattle-lifting. In 1899 it was calculated that, though the Maravans formed only 10 per cent, of the population of the District, they were responsible for 70 per cent, of the dacoities which had occurred during the previous five years.

Larger numbers than usual ot the population of Tinnevelly are occupied in toddy-drawing and selling, weaving, rice-pounding, and goldsmith's work, so that the percentage of agriculturists is less than in most Districts. About two-thirds of the people, nevertheless, live by the land.

Of the total Christian population (1901) of 159,2 [3, as many as 158,809 were natives of India. These belong in about equal numbers to the Roman Catholic Church and the various Protestant denomina- tions. Christian missions have existed in Tinnevelly for upwards of three centuries. The history of the Roman Catholic Church in the District dates from 1532, when Michael Vaz, afterwards Archbishop of Goa, with a Portuguese force assisted the Paravans (fishermen) along the coast of Tinnevelly against the Musalmans, and subsequently baptized almost the entire caste, or about 20,000 souls. In 1542 St. Francis Xavier commenced his labours among these converts. Not much is known of the subsequent history of the mission till about 1 7 10, which is the probable date of the commencement of the labours of Father Beschi, the celebrated Tamil scholar and author of the religious epic Tembdvani. Tinnevelly was always attached to the famous Madura Mission ; and much progress was made until the suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1773 by Pope Clement XIV, when matters languished and were only again revived in 1838 under French Jesuits. Tuticorin is the largest centre of the mission, con- taining three fine churches and many thousands of Christians. The mission has two high schools and more than 100 village schools, besides three convents of Indian nuns and three large orphanages.

Protestant missions in Tinnevelly began with the visit of the famous Swartz to Palamcottah in 1780. The congregation in those early days consisted of only 39 persons. In 1797 began the movement towards Christianity among the Shanans, which is going on at the present day, and which has done much to raise the members of that caste in many ways. At present about 76,000 Christians are connected with the missions of the Church of England, the Society for the Propaga- tion of the Gospel, and the Church Missionary Society. Including some 15 European ladies, about 35 missionaries are working for these bodies. They maintain 750 village schools, with more than 25,000 pupils. They also keep up a second-grade college for boys and another (the Sarah Tucker College) for girls, four high schools for boys and two for girls, four normal schools, an art industrial school, and two schools for the blind and the deaf. Eight hospitals are maintained by them for the treatment of the sick of all classes.

Agriculture

Broadly speaking, the northern half of the District consists of black loam, with a strip of red soil along the foot of the hills south of Srlvilli- puttur ; and the southern half consists of red loam or sand, with a strip of black loam in the valley of the Tambraparni. The black cotton soil plain in the north is a deep deposit, overlying a substratum of rock. There is but Httle irrigation in it, except in parts of Srivilliputtur. The black soils of the valley of the Tambraparni overlie a stiff yellow clay or marl which effectually prevents soakage, and which, keeping the water, vegetable matter, and manure in suspension near the surface, is no doubt the cause of the high fertility of that valley. Much of the high-lying red soil is poor, but in the hollows and along the course of the streams the ground is more fertile. In the south-east stretches a tract of country about 40 miles In length known as the 'palmyra forest,' where the soil is a deep red loam with a surface of sand. In a few well-protected flats the sand merely covers the subsoil ; but in the open country it is several feet deep, and in some places blown up into hills 20 feet high. Even where the sand is deepest, the underlying loam, which is present everywhere, causes palmyra palms to flourish in hundreds of thousands.

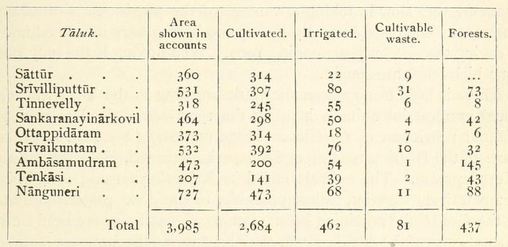

The prevailing land tenure in the District is ryoiwdri, but there are also a number of zamlndaris. The total area is 5,389 square miles ; detailed agricultural particulars for the zamlndaris, however, are not on record, and the area for which accounts are kept is only 3,985 square miles. Statistics of this area for 1903-4 are appended, in square miles : —

The staple food-grains are rice, cholam, catnbu, and rdgi. Rice is cultivated on 467 square miles, or 22 per cent, of the area cropped; cambu comes next, being raised on 195 square miles ; while chola?n and rdgi occupy 134 and 71 square miles respectively. Rice is grown, on only a comparatively small area in the north-eastern tdluks of Sattur and Ottappidaram. Cambu is rarely grown in Ambasamudram and not often in Tenkasi, but elsewhere its cultivation is general and in Sattur and Ottappidaram widespread. Cholam and rdgi are for the most part grown in Sankaranayinarkovil, Nanguneri, and Srivilliputtur, Of the pulses, which are found mainly in the southern and south- western ti'iliiks, horse-gram is the most important. Nanguneri con- tributes most largely to the area under this class of grain. Cotton is the principal industrial crop, being raised on 365 square miles in 1903-4, and Tinnevelly is one of the leading cotton-growing areas in the Presidency. Senna, for which the District was once famous, is still cultivated in the Tinnevelly idhik. Gingelly is of importance in all the tdli(ks except Sattur and Ottappidaram. The cultivation of the palmyra palm and the gathering and preparation of its products, espe- cially toddy, form one of the most important industries in the District. Thousands of people are entirely dependent on this tree for their liveli- hood.

The ryots of the District are generally energetic and industrious, those in the northern taluks, owing probably to the less favourable conditions prevailing there, being more so than their brethren in the south. The advantages of good manure, rotation of crops, &c., are well understood; but no attempt has been made to depart from the old ways, either by introducing new and improved implements or by raising other than the usual staples. An experimental farm has recently been started at Koilpatti, in the centre of the northern half of the District, to attempt to popularize the cultivation of better varieties of ' dry ' grains by improved methods ; but it is too early yet to say how far it will induce the people to move out of the beaten track. The ryots are very slow in taking advantage of the provisions of the Land Improvement Loans Act, only Rs. 29,000 having been advanced under it during the sixteen years ending 1904. Well-sinking is the only work for which loans are sought.

There is little or no systematic cattle-breeding in the District. The usual nondescript animals kept by the ryots are allowed to multiply without restriction or selection. Large cattle-fairs are held in various parts of the District, notably at Sivalaperi, Kanniseri, Kalugumalai, and Muttalapuram. The animals raised in Rajapalaiyam and Sivagiri are comparatively superior, owing, probably, to the good pasture available at the foot of the adjoining hills. Ponies of small size are bred in the eastern parts of the Srivaikuntam tdluk for drawing \\-\tjatkas, or springed hackney carriages, which are used all over the District. There are no noteworthy breeds of sheep or goats.

Of the area cultivated in 1903-4, only 462 square miles were irrigated from all sources. Most of this (267 square miles) was watered from about 2,300 tanks (artificial reservoirs), and a considerable portion (120 square miles) from 52,000 wells. Nearly all the remainder was supplied from Government canals, chiefly those which take off from the Tambraparni. These irrigate the main portion of the ' wet ' land in the Ambasamudram, Tinnevelly, and Srivaikuntam taluks, and are referred to in the separate article on that river. The Tenkasi taluk and parts of Tinnevelly are watered from the Chittar. Nanguneri is irrigated mainly from tanks, some of which are very large, supplied by streams from the hills. The north-western taluks of Sankaranayinar- kovil and Srivilliputtur depend mainly on the north-east monsoon ; and in them irrigation is almost entirely from tanks fed by jungle streams, the supply in which is generally precarious except in favourable years. The black cotton soil taluks of Sattur and Ottappidaram contain very little ' wet ' cultivation. In the sandy portions of Srivaikuntam and Nanguneri water can be easily obtained by sinking shallow holes in the ground, but well-sinking in the black cotton soil is a costly matter.

Forest

The only real forests in Tinnevelly are those which clothe the Ghats on the western border of the District. The approximate area of these is about 520 square miles, of which more than two-thirds is Government ' reserved ' forest, while the rest belongs to the zamin- dars of Singampatti, Settur, and Sivagiri. Small timber of good quality, such as teak, vengai {Pterocarpus Marsupiiwi)^ &c., is found on the sides of the hills. Owing to their value in pro- tecting the head-waters of the rivers and streams, the evergreen forests are very lightly worked.

Early in the last century the attention of the British Government was attracted to the slopes of the Ghats as affording suitable sites for the growth of cinnamon, cloves, and other tropical products of value, and accordingly in 1802 a large number of such plants were put down. These were managed directly by the Government for some time, but were ultimately parcelled out among private owners. Coffee-planting has been tried for several years on the Tenkasi and Nanguneri hills, but has not met with success and the estates are no longer maintained. Oranges, pumplemosses (pomeloes), and mangosteens grow on the Kuttalam hills. An interesting experiment is being carried out in the Srivaikuntam taluk, where an area of nearly 22 miles of shifting sand (teri) is being gradually reclaimed by the planting of palmyra palms wMth under-planting of viru vettai (Dalbergia sympathetica).

No minerals of value have been found in the District. Tradition speaks of copper being washed down by the Tambraparni river ; this probably refers to the great quantities of magnetic ironsand which are brought down from the mountains, but no iron manufacture is carried on, nor have any traces of the existence of such an industry in former days been met with. Small garnets are found on the sea-shore near Cape Comorin. Many fine granitoids exist to the south of Palam- cottah. Granite, limestone, and sandstone are largely quarried for commercial purposes. The fine cream-coloured calcareous sandstone quarried at Panamparai in the Srivaikuntam taluk was used in con- structing the churches at Mengnanapuram and Mudalur, as well as the Hindu temple at Tiruchendiir on the coast. A kind of rock-coral found near Tuticorin is largely used in that town for rough building purposes.

Trade and communications

Cotton-spinning and weaving have long been the leading industries in Tinnevelly. In the early years of last century little raw cotton was exported, but a large quantity was made into cloth in the looms of the District. This local industry has communications. now greatly declined, much of the cotton being ex- ported raw to various parts of the world. A considerable portion is, however, spun in the mills at Tuticorin, Koilpatti, and Papanasam for local consumption as well as for export. At Viravanallur and Kallidai- kurichi, in the Ambasamudram taluk, there is a thriving weaving industry, most of the miindiis, the national dress in Travancore, sold in that State being manufactured at these two places. A kind of coarse towelling is made at Srivilliputtur and the adjoining villages. Melapalaiyam, a suburb of Palamcottah chiefly inhabited by Labbais, is noted for its small cotton carpets, which command a large sale locally.

At Mannarkovil and Vagaikulam near Ambasamudram there is a flourishing brass and bell-metal industry. Reed mats of a peculiarly fine texture are made at Pattamadai near Sermadevi, but the industry is in the hands of a few poor Musalman families and shows no signs of improvement. Good hand-made lace of European patterns is manu- factured in some of the mission stations. The District has earned a name for the superior make and finish of its bullock-carts.

A large proportion of the population of Tinnevelly subsist by in- dustries connected with the palmyra palm, such as drawing toddy from the tree, boiling this down into jaggery (coarse sugar), making mats from the leaves or fibre, and so on. The palmyra industry is in fact the most important in the District, and employs a much larger number of persons than the crafts connected with cotton, though the actual money value of the cotton goods turned out may be greater than that of the produce of the palmyra.

There are a large number of steam cotton-cleaning and pressing factories in the District, situated at Tuticorin on the coast, at Papa- nasam, and at Sattur, Virudupatti, and Koilpatti in the centre of the cotton-growing area. In 1903 the total number of these factories was 16, and they employed more than 1,000 hands. Salt takes the next place. There are ten salt factories in Tinnevelly (those at Tuticorin, Arumuganeri, Kayalpatnam, and Kulasekarapatnam being the most important), with an out-turn (in 1903) of about 64,000 tons of sail, which brought in a duty to Government of nearly 35 lakhs. On the coast are also several fish-curing yards under Government supervision. The immense number of palmyra palms in the District has led to the establishment of three sugar refineries (two at Tinnevelly town and one at Alvar Tirunagari) under native management. Owing to financial difficulties, however, these are not systematically worked at present.

The chief exports from Tinnevelly are cotton, jaggery, chillies, tobacco, palmyra-fibre, salt, dried salt fish, and cattle ; and the prin- cipal imports are cotton-twist and yarn, European piece-goods, and kerosene oil. There are three recognized ports, Tuticorin, Kula- sekarapatnam, and Kayalpatnam ; but the first is the only one which is important. Its trade is noticed in the separate article on that town. There is a considerable export of dried salt fish from the coast to Ran- goon, Madras, and Ceylon. The pearl and chank (Turhlnella rapd) fisheries in the Gulf of Manaar are Government monopolies, but the profit is always doubtful and uncertain. Tinnevelly was once celebrated for its trade in senna. This has now almost died out, as Egyptian senna is considered better and is less adulterated. A considerable volume of trade, chiefly rice from the Tambraparni valley, passes over the trunk road leading from Tinnevelly to Trivandrum. There are two European exchange banks at Tuticorin, and two similar institutions under native management at Tinnevelly. Much of the distribution of the imports and the collection of merchandise for export is done at weekly markets. Some of these are under the control of the local boards, and in 1903-4 the fees collected at them brought in an income of Rs. 7,500. The trade at the seaports is largely in the hands of the Labbais, but Tuticorin contains the agencies of several European firms.

The South Indian Railway (metre gauge) enters the District from the north near Virudupatti, and runs south in an almost straight line to Maniyachi through Sattur and Koilpatti. From Maniyachi it turns east to Tuticorin on the coast, thus completing through communication between Madras city and the chief southern port of the Presidency. From the same place a railway branches off to Tinnevelly, and on to Shencottah on the eastern frontier of Travancore territory, through the fertile idluks of Ambasamudram and Tenkasi. The portion of this last between Tinnevelly and Shencottah was opened in 1903, and has been extended to Quilon on the West Coast through the gap in the Western Ghats near Kuttalam. The District board has also recently resolved to levy a cess under Act V of 1884 for the construction of another much-needed line, on the metre gauge, from Tinnevelly town to Tiruchendur, a famous Saivite shrine on the coast.

The local boards maintain 831 miles of metalled and 100 miles of unmetalled roads. There are avenues of trees along 889 miles of them. The centre upon which all the main lines of communication converge is Tinnevelly town. The trunk road from Tinnevelly to Madura has lost much of its importance since the opening in 1876 of the South Indian Railway, which runs nearly in the same direction. Another important line of communication is the road from Tinnevelly to Nager- coil in South Travancore via Nanguneri. Most of the trade between Tinnevelly and Travancore used to be carried over this route before the recent opening of the railway to Quilon.

Famine

The District generally is not liable to serious droughts, but the northern taluks and Nanguneri are affected in years of scanty rainfall. 'Unnevelly suffered somewhat in the great famine of 1876-8, but the distress was not as severe as in other Districts. Relief-works were started in December, 1876, but they were discontinued in May, 1877, and gratuitous relief was given for only a short period. The highest number relieved in any one month was only 23,000. The distress, however, necessitated the grant of remis- sions of revenue amounting to 17/2 lakhs. Since then the District has suffered slightly from deficient rainfall in several years. In 189 1-2 remission of the assessment on unirrigated land to the extent of nearly Rs. 66,000 and on 'wet' land of over 4 lakhs was granted, and about 875 people on an average were employed daily on relief-works from March to August, 1891. The recent opening of the Quilon branch of the South Indian Railway, which traverses the whole length of the Ambasamudram and Tenkasi taluks, touching all the important towns and centres of trade, will in future facilitate the collection and distri- bution of grain over all parts of the District.

Administration

There are four subdivisions in the District, all of which, except the head-quarters charge comprising the taluks of Tinnevelly and Sankara- nayinarkovil, are at present managed by officers of the Indian Civil Service. The Tuticorin sub- division comprises the two large taluks of Ottappidaram and Srivai- kuntam. The taluks of Nanguneri, Ambasamudram, and Tenkasi, lying at the foot of the Ghats, form the Sermadevi subdivision. The Sattilr subdivision, formerly under a Deputy-Collector but recently placed in charge of a member of the Indian Civil Service, includes the two northern taluks of Sattur and Srivilliputtur. A tahsilddr is posted at the head-quarters of each taluk and a stationary sub-magistrate also. In addition, there are deputy -tahsildar magistrates at Palamcottah, Vilatikulam, Tuticorin, Radhapuram, Varttirayiruppu, and Virudupatti. Palamcottah is the head-quarters of the District Judge, the District Superintendent of police, the District Surgeon, the Executive Engineer and District Forest officer, and of the Bishop of Tinnevelly.

Civil justice is administered by a District Judge, two Sub-Judges — one at the District head-quarters and the other at Tuticorin— and seven District Munsifs, two of whom are stationed at Tinnevelly and the other five at Srivilliputtur, Sattur, Tuticorin, Srivaikuntam, and Ambasamudram respectively. There are, in addition, nearly 420 village courts for the disposal of petty suits under Madras Act I of 1889, The District is one of the most litigious in the Presidency, contributing nearly 7 per cent, of the total number of suits annually filed.

Besides the Court of Session, the Additional Sub-Judge at Tuticorin is also authorized to try criminal cases as Assistant Sessions Judge. The District contributes about 5 per cent, of the total number of criminal cases in the Presidency, and has an unenviable reputation for dacoity, robbery, and house-breaking. The followers of the poligdrs (local chieftains) of the Maravan caste used, in the days before British rule, to live mainly by plunder, and the predatory spirit still survives in their descendants. Kdval fees, a relic of the old blackmail levied by these chiefs, are still paid all over the District by villagers as the price of exemption from molestation by these people, except in a few villages which have been strong enough to make a stand against this extortion. A movement to throw ofif the system is spreading among the people, but experience proves that it is most difficult to eradicate. The antipathy which has long existed between the Maravans and the Shanans, culminating in the unfortunate riots of 1899, has for long been a source of anxiety to the District officials. Special police forces have been temporarily stationed at the centres where disturbances are most likely to arise, and the preventive provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code have been systematically put into operation. Special schools have also been started in the more important centres of the Maravans, to disseminate education and the principles of honest living among this caste.

No exact details are available regarding the land revenue system which prevailed in Tinnevelly under the Naik Rajas of Madura. It is usually supposed that they were content with one-sixth of the gross produce, but wilks says that one-third was the usual proportion taken from ' dry ' land. There is no doubt their assessments were light in comparison with those of the Musalmans who succeeded them.

The Hindu government was subverted by the Musalmans between 1736 and 1739. From 1739 to 1801, when the British finally assumed control of the country, a succession of managers were de- puted to administer the revenue of Tinnevelly. Of these fifteen were Musalmans, nine were Hindus, and two were British officers. From 1739 to 1770 the assessment was paid in kind, land watered by the Tambraparni or from never-failing watercourses being charged twice as much as fields irrigated from tanks, There were, however, additional cesses, collected in money, which varied from time to time. In 1770 the system of dividing the crop between the cultivator and the Govern- ment was introduced. The latter took 60 per cent, of the gross out- turn on ' wet ' land, after first deducting some small cultivation expenses and money cesses. This share was reduced to 50 per cent, in 1780, and continued at that rate till 1800.

In 1801,when Mr. Lushington took charge of the District on behalf of the Government, he commenced operations with the measurement of all land, both ' wet ' and ' dry,' and an attempt at the classification of the latter. Subsequent administration differed according as the land was 'wet' or 'dry.' In the 'wet' villages the system of division of the crop was continued, the Government share being raised to 60 per cent, in 1803 and the other demands continuing as before. The evils of this system (which are described in detail in the Tinnevelly District Manual, pp. 71-2) led to the adoption, in 1808, of a three years' village lease, by which the villages were rented for fixed money payments to their inhabitants. The payments were calculated on the average collections of previous periods, with a deduction to compensate for the undue exactions of the officials of the Nawabs, and a system of monthly instalments was introduced by which the demand was distri- buted over the eight months between December and September. This village lease system was a failure owing to various causes, the chief being a fall in the price of grain, and was not continued. In 1813 decennial leases, based on much the same principles, were introduced into the irrigated villages of the Tambraparni valley, but villages which objected to it were allowed to revert to the system of division of the crop. By 18 14, only 106 of the 1,177 villages in the valley remained under this latter system, the rest having accepted the decennial lease. In 1820 the Collector recommended a reduction of 12 per cent, in the rentals fixed for the decennial leases in the ' wet ' villages. The altera- tion actually made was the introduction of the ohmgu system, which came into force in 1822 and lasted till 1859. This consisted in the payment to Government of an assumed or estimated share of the pro- duce, the value of which was commuted at a standard price modified by the current prices of the day. It was advantageous to the ryots and eventually altogether displaced the system of division of crops. In 1859 the mottavifaisal system was introduced. This was a modification of the olungu method, the variations in the conversion rate according to current prices being abandoned, and a standard price adopted once for all as a permanent conversion rate. As prices soon after began to rise, while the fixed rate was low, this alteration was greatly in favour of the ryots and resulted in a rapid increase of cultivation.

The revenue history of ' dry ' villages is different. During the time uf the Nawabs the renters levied a lump annual assessment on them, which was distributed among the several cultivators by the chief ryots on a classification of the soils of the various holdings. In 1802 Mr. Lushington fixed the rates on these fields by taking the average collections of former years as his standard, and for some yearb his assessments underwent alternate reduction and enhancement. In 1808 they were permanently reduced to rates which varied, according to the soil, from Rs. 2-5 to 10 annas per acre; and they remained the same, with a few unimportant alterations, till 1865.

The various experiments above described left the assessment of the land revenue payable by the individual ryot very much to the discretion of the chief inhabitants, and the results were frequently unsatisfactory. The Government accordingly at length resolved to resettle the land revenue on the ryotwdri principle. This resettle- ment was begun in 1865 and completed in 1878, and was ordered to continue in force for thirty years. It was preceded by a com- plete survey of all the land in the District ; and, though this proved that the area in occupation was 7 per cent, in excess of that shown in the accounts, the assessment arrived at was 7 per cent, less than before. The average assessment per acre on ' dry ' land is now R. i (maximum Rs. 5, minimum 3 annas), and on 'wet' land Rs. 6 (maximum Rs. 12, minimum Rs. 2). The period of this settlement has already expired, and a resurvey and resettlement was undertaken towards the close of 1904 in the Tinnevelly, Tenkasi, and Amba- samudram taluks.

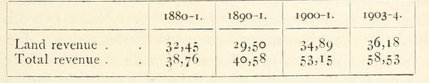

The revenue from land and the total revenue of the District in recent years are given below, in thousands of rupees : —

Local affairs are managed by a District board composed ot 32 members, and by the four taluk boards of Tinnevelly, Tuticorin, Sermadevi, and Sattur, the areas under which are identical with the subdivisions of the same names. There are also 36 Unions established under Madras Act V of 1884, of which 22 have a population of more than 10,000 each. Next to Madura, Tinnevelly contains the largest number of such Unions in the Presidency. The income of all the local boards in 1903-4 was Rs. 5,43,000, of which Rs. 2,77,000 was contributed by the land cess and about Rs. 60,000 by tolls. The expenditure in the same year was Rs. 5,30,000, of which Rs. 2,60,000 was devoted to the construction and upkeep of roads and buildings, the other chief items being education, sanitation, and vaccination.

Police affairs, as in other Districts, are managed by a District Super- intendent. He is stationed at Palamcottah, and is helped by an As- sistant Superintendent at Tuticorin and a Special Assistant at Sivakasi, who is in charge of the special temporary forces mentioned below and also does general police work. There are 85 police stations and 1,087 constables under 19 inspectors, besides 1,182 rural police under the control of the tahsllddrs. Special temporary forces have been stationed at Sivakasi, Koilpatti, Surandai, and Marugalkurichi, in consequence of the Shanan riots already referred to. The Dis- trict jail is at Palamcottah, and there are 15 subsidiary jails, with accommodation for 255 prisoners.

In the matter of education, Tinnevelly (according to the Census of igoi) ranks fifth among the Districts of the Presidency, 10 per cent, of the population (19 per cent, males and 1-5 per cent, females) being able to read and write. Education is most advanced in the taluks of Tenkasi, Ambasamudram, and Tinnevelly along the valley of the Tambraparni, and most backward in the cotton soil portions of the District. The total number of pupils under instruction in 1880-1 was 34,863; in 1890-1, 53,130; in 1900-1,66,283; and in 1903-4, 73,726, of whom 10,819 ^^'6^6 girls. On March 31, 1904, there were 1,297 primary, 75 secondary, and 11 special schools, besides 3 col- leges. There were in addition 538 private schools, with 13,196 male and 544 female scholars. Of the 1,386 educational institutions classed as public, 2 were managed by the Educational department, 58 by local boards, and 7 by municipalities, 1,052 were aided from public funds, and 267 were unaided. Of the male population of school-going age 29 per cent, were in the primary stage of instruction, and of the female population of the same age about 6 per cent. Among Musalmans the corresponding percentages were 90 and 8. About 150 schools are maintained for Pancharaas or depressed castes, with 5,600 pupils. Chiefly owing to missionary influence, female education is compara- tively advanced in Tinnevelly, there being 1,900 girls in secondary and nearly 8,200 in primary schools. There were also nine girls reading in the collegiate course at the Sarah Tucker College at Palamcottah. The great majority of the girls belong to the native Christian community. The two Arts colleges for males are in Tinnevelly town. About Rs. 4,65,000 was spent on education in 1903-4, of which Rs. 1,30,000 was derived from fees. Of the total, Rs. 2,60,000 was devoted to primary education.

There are 11 hospitals and 12 dispensaries in the District. Seven of the former and nine of the latter are maintained by the local boards, and the remainder (four hospitals in the municipal towns and' three dispensaries, two in Tinnevelly town and one in Palamcottah) from municipal funds. Besides these, the various mission agencies have established four hospitals and three dispensaries. These institutions have accommodation for 109 male and 73 female in-patients. A Local fund hospital for women and children has recently been built at Palam- cottah. About 339,000 persons, of whom 2,500 were in-patients, were treated in 1903, and 10,000 operations were performed. The total cost of all the institutions was Rs. 61,000, which was mainly met from Local and municipal funds, and to a small extent from the income of endowments, and (in the case of mission hospitals) from subscriptions.

Vaccination has always been fairly satisfactorily conducted in Tinne- velly, and in 1903-4 a large number of operations were performed at the comparatively low cost for each successful case of 3 annas i pie. The proportion of successful operations per 1,000 of the population was 39-4, which again was the highest rate in the Presidency except in the Nilgiris. Vaccination is compulsory in the municipalities and in 19 out of the 36 Unions.

[Further particulars of Tinnevelly District will be found in the District Manual by A. J. Stuart (1879), and in Bishop Caldwell's History of Tinnevelly (1881).]