Syed Haider Raza

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A profile

Gayatri Jayaraman

February 27, 2015

At 93, S.H. Raza paints every day

A turquoise blue light filters through the stained glass above the altar of the Franciscan arches of the Sacred Heart Cathedral in Delhi, falling upon a diminutive fi gure in an ash-grey suit in a wheelchair in the fi rst pew. Artist S.H. Raza seems oblivious to the greys and blues that are synchronously the current palette of an ongoing Bindu on his easel, back in his studio. Now hard of hearing, losing vision, shrunken by his liquid-only diet, Raza tilts his head to listen to the benediction being read for his 93rd birthday. It is a Raza trans-posed into the core of one of his works, the several hillside churches of Europe that occur in his early landscapes, before the Bindu became his perenni-al obsession and expression. In life, as on canvas, there is no more a separa-tion between the artist and his art. As his closest friend and fellow Modern, the now 90-year-old Krishen Khanna, himself recovering from a 20-footlong art work that took eight months to complete and put a pacemaker in him, says: "There is no more a distinc-tion between Raza and his Bindu, he is living his art".

The master at workBack in his studio, as Raza takes to his canvas where his assistants not only lift him onto his seat but pour colours to his specifi cations, his col-league-turned-caretaker-and-inter-preter, Ashok Vajpeyi, trustee of the Raza Foundation along with Ashok Vadehra, remarks: "Now his fi ngers are his eyes." The art is his meditation and consumes him. "It is a religious perception of colour. Just as you would say Ram, Ram, Ram, or Allah, Allah, Allah, you say Bindu, Bindu, Bindu. It leads to an understanding of life, the mysteries of life, and in painting, the mysteries of colour. All colours emanate from it. Then, with the colours that appear, you paint," says Raza.

Aarambh, the exhibit of Raza's 44 unseen canvases done across 2013 and 2014 (nine-odd 2015 works line his studio still), went up for preview the previous evening at Delhi's Vadehra Art Gallery. The three-part exhibit to celebrate his birthday also is on at Art Musings, Mumbai, and Akar Prakar in Kolkata. The canvases bear the exertions of his labour-the heavier-handed drop, the smudged intersections, the wavering smear. It is as if with age, Raza's carefully constructed geometrical edges blur. Within their engagement lie his biggest truths. "Newspapers do not write about the intersection, the meeting point of two colours. Therein lies all conflict and all harmony," he says. He is well aware of his diminished ability, and paints with an awareness of the spaces in which he triumphs over it. "It is important that the painter deal with the subject; that is the importance of the mass of colour, be it a hand that shakes or a line, it is a form that is in contact with another form-that is the importance of a painter and the importance for his onlooker." The range of his palette too has shifted. From the warmth of his mid-70s strident reds and blacks, blues and yellows now dominate. He laughs at the play of the spectrum. He has brought it down to a science, he says, pointing to his painted gradations on the wall: in it the panchatatva (five elements) are each represented by a colour on Raza's brush-black, red, blue, yellow, white. Different colours have dominated at different phases of his career. As they emerge, he says, it has been his effort to control them. Yellow turns to orange, orange to brown, and brown to black. Or, as he teases, a twinkle in his eye: "Have they dominated me, or have I dominated them?" It is more a riddle than a question. The protagonist to his canvas remains the strident black Bindu. And while it is from what the other colours and elements and energies all emanate, it is yet the inversion of the spectrum that traditionally emerges from white. Raza, amused, chuckles. "Yes, but they are looking at the end of the spectrum-that into which it is all consummated. I look at the beginning, where it is all yet potent. White is integrated into the Bindu. It can be a part of black, but black can never be a part of white. The black is in which all is contained. White is the energy that is glowing right from the darkness of black, and from which red, yellow, blue and grey emerge. This is why the works are called Aarambh, the beginning," he says.

Within that range, all energies are in conflict and harmony with each other, he explains. "The colour you choose to place next to another is either in a state of seeking conflict or harmony with its neighbour, and that resonance, that which is between the line, is the energy of the painting," he says. In his smudges and his smears then, the disturbances of the outer concentric circles are an almost primal dance which come to calm in the centre. It is inherent in his move from deeper to lighter tones. As he feels his way through his palette, he etherises his own inherent geometric boundaries. "Oh that chap, he is a master manipulator of colour. He can make any colour say whatever it is he wants it to say," chuckles Khanna, himself partial towards the warmth of the red. Colours have been very particular to the Moderns, all of them master wielders of its strength; M.F. Husain playing with monochromes of yellow in his 'Peeli Dhoop', V.S. Gaitonde infusing them with the sonority of a temple bell, and Akbar Padamsee still engaged with his plays of light and abstraction. "It is only because the Indian artists understood the importance of colour that the world is realigning to the point of view of Indian art today," Raza says. He breaks it down to the dot, or the atom. "It is not that you painted a portrait. It is the elements you used to paint the portrait. And when you realise the importance of those, the painting becomes important. It is the use of the colour and the relationship in its use on a canvas that makes a painting a work of art."

This theory of colour, of conflict and harmony, from black to white, today consumes Raza's entire thinking: social, political and aesthetic. You have to put the colours together as two human beings, says Raza. "It is a man and a woman coming together. Either they fight or they make love. Whatever style one may have, this relationship of colours remains true, remains the geometry of life." All of society, and nature, and primal instinct are tinged with this essential conflict. Whatever your practice of art-creative, abstract, figurative, or performance even-the basic truth remains the same, he emphasises. "Whatever element a woman chooses to wear, it is like what a painter chooses to paint with. When a woman decides to wear a cloth, whether a kurta or a sari, she is making a choice of colour. There is an expression of an inner tatva," he says. In picking that colour, there is resonance, and conflict or harmony is established. Much like the spaces with his lines, increasingly indented with greater flecks of white, in his new canvases. "This is why," he says, finally allowing himself to lean back into his chair, "the Bindu is the most important thing of all."

Fellow Progressives Khanna and Ram Kumar still come across for tea when they can. "We do not talk of this and that. We talk of art, and concerns, and colour," Raza says. Founder of the Progressive Artists' Group, the Moderns' devotion to conversation and sharing of knowledge is crucial to their identity. It is a group in the remnants of which the artists still provide each other with critical and emotional support. "Thinking is meditation-a point at which it is not separate from doing, or painting," says Raza. Khanna, still critical of Raza's geometry, what he calls an imposed lifelessness of structure on his art, binding, and restrictive, explains that they were never a group formed to pat each other on the back. "We were not each others' 'yaysayers'. The function of the group was to propel each other into new ways of thinking and allow our art to grow. The ultimate purpose of everything we believed in was growth." Raza's devotion to structure began when French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson came across his student work in an exhibit in Srinagar, and told Raza that he had talent but no plinth to build on. Raza returned to Bombay and devoted himself to exploring the geometry of paintings as keenly as its abstractions.

Vajpeyi points to Raza's generosity with not only his knowledge but also his wealth. Returning to India in 2006, after the death of his wife and fellow artist Janine Mongillat in 2002, the heirless Raza's primary intent was to create a fund that would allow young artists to escape what he describes as the "dark days" after his studies at the JJ School of Art in Bombay. No one was buying his art. When he arrived in Bombay in 1943, he could not enrol right away in college as the government scholarship he won was delayed, so he began to paint at the Express Studio in Fort. When he went to Paris on a French government bursary to study at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in 1950, he did not have the money for a coat warm enough to withstand the Parisian winter. It was The Times of India critic Rudy von Leyden who gave him one. Years later, when artist Atul Dodiya was leaving for Paris, history repeated itself; Raza gave him money to buy himself a winter-worthy coat. And so the baton passes. Today, the Raza Foundation publishes three journals, puts out seven memorial lectures, and funds both performing and visual arts through awards, fellowships and grants, as well as to projects that revive and document the memory of now-forgotten Progressives such as K.H. Ara and S.K. Bakre. Raza even pays rent staying in his rooms at the Raza Foundation building in Delhi's Safdarjung Development Area. Himself a large-scale collector of art, Raza's ailing health impedes his ability to view new artists, but the encouragement of new art is an undertaking that has occupied him for most of his return to India.

In the early 2000s, Raza visited the debut showing of artist Smriti Dixit in Mumbai and made it a point to be the first to buy one of her works and leave. The next morning, the grateful gallerist called. Word had spread that Raza bought, and thereby endorsed, the artist, and her show was sold out within the hour. With such deliberate consideration of the artist's struggle, Raza has often called up gallerists and offered to buy on the condition that commissions were waived. Today, Raza pays income tax of around Rs 2 to 3 crore every year and is devoted to the idea of what will linger beyond him in the name of Indian art.

To understand the frontiers he breached on behalf of Indian art, it is important to go back to the day in 1956 that Raza was awarded the Prix de la Critique in France, says Khanna. He recalls being at the Jehangir Art Gallery in Mumbai, when Cowasji Jehangir hushed the room and stood up to make the announcement. The room, says Khanna, erupted in thunderous applause. "It was such pride, such pride. He was our boy you know, he'd gone there and he'd done it. It was not easy in those days. None of us had the means, and none of us knew what we were in for. We just knew what we believed in. Those were frontiers that he was breaching for us. Now it would be possible for us too." The nitty-gritty of Raza's expansive and generous life are well documented. His birth in 1922, and the influence of his early childhood in the forests of Madhya Pradesh, passages to Nagpur, Bombay, France and California, his founding of the Progressives as a group and their lifelong friendships that shaped the course of Indian art.

The ne plus ultra of Raza's existence and practice today is the sublimation of everything to the resonance of its colour. This cumulative of lifelong learning, decades of conversation and thought is the essence of a Hindu complexity of metaphysics, a Christian beatitude and the Muslim riyaz of rhythmic repetitiveness. Of all the Moderns, rationalists to the very end, Raza stands out for his being the eternal Believer: beliefs that he now merges with. "Everything emanates from it. If the Bindu disappears, I can't even imagine....." he trails off.

Contributions

The Hindu, July 24, 2016

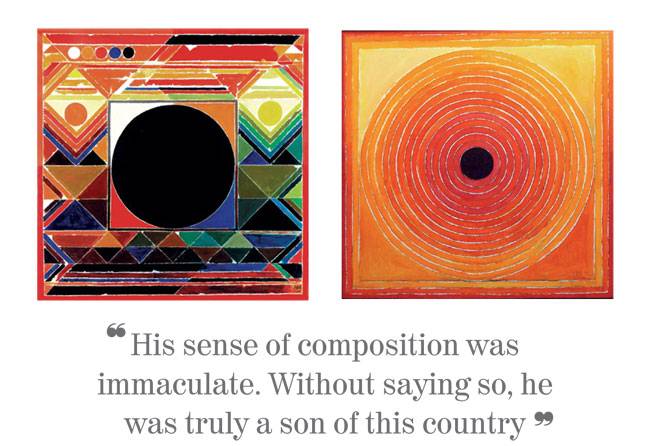

It’s the simplicity of the paintings that strikes you at first glance. A black circle with concentric lines radiating from that dark centre, a neat arrangement of triangles and straight lines; dabs of paint that never spill out of their cells, colours that glisten with vibrancy long after the paint has dried; perhaps a few words written in Hindi at the bottom. Wait a moment, let your eyes adjust to the brightness of the chosen pigments, and the painting starts revealing itself to you — its pristinely perfect geometry, the delicate and precise alignment of planes and pivots, the calculated nuances of shade, tint and colour; the magnetic blackness of the bindu.

Syed Haider Raza’s circle was completed when, at 94, one of modern Indian art’s most legendary names breathed his last in Delhi. Born in a speck of a town in Madhya Pradesh, Raza travelled first to Nagpur, then to Bombay as it was known then and finally to Paris, all on the wings of his art. He was one of the legends of our art history and with him gone we have lost our last link to the era of the Progressives who in anger and elegance raged against established traditions.

A new aesthetic

Formed in the 1940s, the Progressives began fashioning a new Indian aesthetic that was diverse, impossible to pin down and yet distinctively our own. It rebelled against the romanticism of the Bengal school and rejected the conventions of classical European art. What emerged was art that powerful and negotiating myriad and traditions — just like the young India that had just secured independence.

In many ways, Raza was the most accessible of the Progressives. He didn’t have the angular rage that bristled out of F.N. Souza’s paintings. His paintings weren’t provocative like M.F. Husain’s. They didn’t disturb as much as reiterate a certain sense of harmony. In Raza’s most memorable paintings, everything is in equilibrium. On his canvases, particularly the geometric ones that he started creating at his artistic peak in the 1980s, was a world of feeling and abstraction that was like a portal rather than a painting.

Uncomplicated modernity

Raza’s art embodied an uncomplicated yet diverse Indian modernity — an artist with a Muslim name, drawing upon both Hindu and Islamic philosophy with his bindus and his use of geometry, taking colours and shapes from folk art, creating paintings that were undeniably contemporary. He was also among the first of the Indian artists to go and live abroad — Raza spent decades in Paris, having moved there when he was 28. He had chosen the city because he was determined to see the paintings of Paul Cézanne. He stayed on and it became his home and yet the canvases were filled with kaleidoscopic fragments of the home he had left behind, arranged in careful and beautiful patterns.

He once said that he hadn’t really left India. He said that he had carried India with him and surrounded himself with the country as he knew it through his paintings. In the colours that he chose and the shapes that he used, there was a landscape of memory and nostalgia.

What gave his paintings the energy was that sense of nostalgia and longing perhaps because Raza’s finest paintings were created when he was far away from home. Yet even when he came to India and made his home in Delhi, he continued to work and what he produced still characterised that easy and unlaboured fusion of traditions and ideas. There is no statement that he is making and neither is there any need to prove his adherence to any stream of thought or belief. At their best, Raza’s abstract, geometric paintings hum with energy. At their blandest — and there are a fair number that fit this description since Raza diligently painted in his studio every day until his body gave way a few months ago — they are simple and beautiful. Either way, they are at peace.

Today, in an age when we are struggling to find harmony in a society that seems to be more violently fragmented with every passing day, Raza’s paintings are a reminder of the times past and confluences that we no longer seem to be able to find around us.

The Modernist

Gayatri Sinha , Bindu.Period “India Today” 8/8/2016

The first generation of Indian modernists not only dominated Indian art for the last six decades, they were also unusually long-lived and influential. With the passing of Syed Haider Raza in New Delhi on July 24 at the age of 94, another citadel has fallen. Raza, a graduate of Bombay's JJ School of Art, had founded the Progressive Artists' Group in 1947 with M.F. Husain, Tyeb Mehta, H.A. Gade, S. Bakre and K.H. Ara. Coming mid-century and post-Independence, this motley group - including a Dalit, a Goan Christian and two Muslims - has come to represent some of the finest values of modernity in a newly minted nation. In their expansive careers, the modernists have been both vilified and celebrated, but most importantly, their work has endured the vicissitudes of the Indian art scene.

Raza was at the forefront of a concerted push towards modernity. Born in 1922 in the Mandla district of Madhya Pradesh, he was the son of a forest ranger and grew up close to the elements of nature his paintings came to celebrate. His carefully crafted career was to become a beacon for at least two generations of artists. When his family chose to migrate to Pakistan during Partition, Raza stayed on. At the time, his Kashmir landscapes set the tone for his forthcoming engagement with the School of Paris. He travelled to the French capital in 1950, in pursuit of the modernity the PAG so passionately sought. In the early years, the group continued its close rapport. Krishen Khanna speaks of the first exhibition Raza, Akbar Padamsee and F.N. Souza mounted together at the Gallery Cruz in Paris. "Souza and Padamsee painted in a quasi-modern fashion. Raza, however, made a throwback to the Mughal period, creating jewel-like water colours, with the pigment rubbed in with a shell. He was vastly successful and acquired by important collectors."

During his early years in Paris, Raza began to paint very distinctive, unpeopled cities with silent echoes, dominated by a black sun. With Haut de Cagnes (1951), the burning landscape with fragile homes, he announced his growing mastery. In 1956, he was awarded the prestigious Prix de la Critique; it was a signal moment for the small but significant art scene in India. Settling in Paris, offering advice and hospitality to Husain, Ram Kumar, Krishen Khanna and a generation of younger artists, Raza from the '50s signalled the success of the Indian artist with an international reputation.

By the late '60s, early '70s, Raza's painterly style rested on the successful integration of cultures and styles, where his native Mandla merged with his chosen home in the village of Gorbioin in France, translating on canvas as Indian tantric symbols blended with an international geometric abstraction.

The story behind this synthesis is apocryphal. As a boy in Mandla, a teacher taught him to concentrate on his studies by focusing on a dot on the wall. Years later, the dot was to expand as the cosmic black sun and then the Bindu. The flowing, tensile strokes of his abstract painting, inspired by Russian painter Nicholas de Stael in the initial years, made way for the circle, the square and descending triangle, a language suited to both the inspirations he paid homage to. It is an endlessly renewable language, with the Bindu manifesting as plastic form to signify a vast poetics of scale and symbol, from seed to cosmos. "His sense of composition was immaculate. Without saying so, he was truly a son of this country," says Krishen Khanna, a close friend and fellow associate of the Progressive artists.

Through the '90s, Raza's imagery came to be more and more rooted in the land of his birth. With the circle/sun, the square and the triangle as basic principles, he moved to the Mandala, Kundalini or Naad, the use of poetry and text set against the blazing colours he so admired from Indian painting allowed each work to stand like a field of energy. Working with a fast-drying medium like acrylic, he was a highly productive painter. Raza was awarded the Kalidas Samman in 1997 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2013.

Raza's 60-year Paris interlude was followed by his return to India, after wife Janine's death. As an octogenarian, the artist now reached beyond himself, much like the ever-widening concentric circles of his paintings. In this last decade, a visitor to Raza Foundation would have spotted him seated before his easel, the outlines of the sun tremulous but still consistent. In these years, Raza had stepped beyond his own practice to institute the Raza Foundation (2001). Steered by eminent poet Ashok Vajpeyi, it is the only such initiative by an artist that supports thinkers, artists and writers in the public domain. Raza's lasting influence on abstraction as practised by a younger crop of artists from MP is another aspect of his legacy, and may well prove to be the most enduring.