Sundarbans

Contents |

Introduction

This section has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts.Many units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

A vast tract of forest and swamp, extending for

about 1 70 miles along the sea face of the Bay of Bengal from the estuary

of the Hooghly to that of the Meghna, and running inland to a distance

of from 60 to 80 miles. The most probable meaning of the name is the

'forest of sundri’ (Heriiiera lilioralis), this being the characteristic

tree found here. The tract lies between 21° 31' and 22° 38' N. and

88° 5' and 90° 28' E., with an area of 6,526 square miles, of which

2,941 are included in the District of the Twentv-four Parganas,

2,688 in Khulna, and 897 in Backergunge.

Physical aspects

The Sundarbans forms the lower part of the Ganges delta, and is

intersected from north to south by the estuaries of

the river, the most important, proceeding from west

to east, being the Hooghly, Matla, Raimangal,

Malancha, Haringhata, Rabnabad, and Meghna. The tract through which they flow is one vast alluvial plain, where the process of land- making has not yet ceased and where morasses and swamps, now gradually filling up, abound. The rivers are connected with each other by an intricate series of branches, and the latter in their turn by innumerable smaller channels ; so that the whole tract is a tangled network of streams, rivers, and watercourses enclosing a large number of islands of various shapes and sizes. Cultivation is confined to a fringe of reclaimed land situated along the northern boundary, except in Backergunge, where some of the clearings extend almost down to the sea.

The flat swampy islands are covered with dense forest, the most plentiful and important species being the sundri, which thrives most where the water in the channels is least brackish. Towards the north the forests contain a rather dense undergrowth, but elsewhere this is very scanty. In the north some mangroves, chiefly Kandelia and Bruguiera, are found scattered along the river banks; farther south, as the influence of the tide increases, they become more numerous, Ceriops and Rhizophora now appearing with the others, till at length the riparian vegetation is altogether mangrove. By this time too, sundri and its associates largely disappear from the interior forests, which are now mainly composed of geoa (Excoecaria Agallocha). Nearer the sea this in turn gives way to mangroves. This pure man- grove forest sometimes extends into the tide ; but at other times it is separated from the waves along the sea face by a line of low sand- dunes, on which reappear some of the swamp forest species, ac- companied by a few plants characteristic of other Asiatic shores, such as Erythrina indica, Thespesia populnea, Ficus Rumphii, and others for which the conditions in the swampy islands of the interior seem to be unsuited.

The wild animals include tigers, which cause much destruction, rhinoceros (now nearly extinct), buffalo, hog, spotted deer (Cervus axis), barking-deer (Cervulus muntjac), and hog deer (Cervus porcinus). The rivers are infested with crocodiles, which are dangerous to man and beast ; and the cobra, python, and many other varieties of snakes are found. In the cold season, geese, duck, and other birds con- gregate in large numbers on the sandbanks.

The average annual rainfall varies from about 82 inches in the west to over 200 inches in the east. Cyclones and storm-waves occur from time to time. The worst of the recent calamities of this nature was in 1870, when a great part of Backergunge and the adjoining Districts was submerged, the depth of water in some places being over 10 feet. An account of this catastrophe is given in the article on Backergunge District.

Nothing is known of the Sundarbans until about the middle of the fifteenth century, when a Muhammadan adventurer, named Khan Jahau, or Khanja Ali, obtained a jagir from the king of Gaur, and made extensive clearances near Bagherhat in Khulna ; he appears to have exercised all the rights of sovereignty until his death in 1459. A hundred years later, when Daud, the last king of Bengal, rebelled against the emperor of Delhi, one of his Hindu counsellors obtained a Raj in the Sundarbans, the capital of which, Iswaripur, near the Kaliganj police station in Khulna, was called Yasohara and has given its name to the modern District of Jessore. His son, Pratapaditya, was one of the twelve chiefs or Bhuiyas who held the south and east of Bengal, nominally as vassals of the emperor, but who were practically independent and frequently at war with each other. He rebelled but, after some minor successes, was defeated and taken prisoner by Raja Man Singh, the leader of Akbar's armies in Bengal from 1589 to 1606.

It is believed that at one time the Sundarbans was far more exten- sively inhabited and cultivated than at present ; and possibly this may have been due to the fact that the shifting of the main stream of the Ganges from the Bhagirathi to the Padma, by diminishing the supply of fresh water from the north, rendered the tract less fit for human habita- tion. Another cause of the depopulation of this tract may be found in the predatory incursions of Magh pirates and Portuguese buccaneers in the early part of the eighteenth century. It is said that in 1737 the people then inhabiting the Sundarbans deserted it in consequence of the devastated state of the country, and in Rennell's map of Lower Bengal (1772) the Backergunge Sundarbans is shown as 'depopulated by the Maghs.' The most important remains are the tomb of Khan Jahan and the ruins of Shat Gumbaz and Iswaripur in the Bagher- hat subdivision of Khulna District, the temple of Jhatar Dad in the Twenty-four Parganas, and the Navaratna temple near Kaliganj police station in Khulna.

Population

The majority of the present inhabitants have come from the Districts immediately to the north of the Sundarbans, and consist chiefly of low- caste Hindus and Muhammadans, the Pods being the most numerous Hindu caste in the west and the Namasudras or Chandals towards the east. The Muhammadans, who are numerous in the east, belong mostly to the fanatical sect of Farazis. In the Backergunge Sundarbans there are some 7,000 Maghs who came originally from the Arakan coast. Between the months of October and May crowds of wood-cutters from Backergunge, Khulna, Faridpur, Calcutta and elsewhere come in boats and enter the forests for the purpose of cutting jungle. The coolies whom they employ to do jungle-clearing, earthwork, &c., come from Hazaribagh, Birbhum, Manbhum, Bankura, and Orissa. There are no villages or towns, and the cultivators live scattered in little hamlets. Port Canning was at one time a municipality, but is now nearly deserted ; Morrelganj in the Khulna District is an important trading centre.

Agriculture

The reclaimed tract to the north is entirely devoted to rice culti- vation, and winter rice of a fine quality is grown there ; sugar-cane and areca-palms are also cultivated in the tracts lying in Khulna and Backergunge Districts, When land is cleared, a bdtidh or dike is erected round it to keep out the salt water, and after two years the land becomes fit for cultivation ; in normal years excellent crops are obtained, the out-turn being usually about 20 maunds of rice per acre.

Forests

The Sundarbans contains 2,081 square miles of 'reserved' forests in

Khulna District, and 1,758 square miles of 'protected' forests in the

Twenty-four Parganas. These are under the charge of a Deputy-Conservator of Forests, aided by two assistants, whose head-quarters are at Khulna. The characteristics of the forests have been described above. They yield an immense quantity of timber, firewood, and thatching materials, the minor produce consisting of golpada (Nipa fruticans), hantal (phoenix palu- dosa), nai, honey, wax, and shells, which are burned for lime. The ' protected ' forests in the Twenty-four Parganas are gradually being thrown open for cultivation, and 466 square miles were disforested between the years 1895 and 1903. The gross receipts from the Sundarbans forests in 1903-4 were 3.83 lakhs, and the net revenue 2.71 lakhs.

At Kaliganj, in Khulna District, country knives, buffalo-horn

combs, and black clay pottery are made.

Trade and communications

Rice, betel-nuts, and timber are exported to Calcutta.

Port Canning on the Matla river is connected with Calcutta by rail ; but, apart from this, the only means of communication are afforded by the maze of tidal creeks and cross-channels by which the Sundarbans is traversed. These have been connected with one another and with Calcutta by a system of artificial canals (described under the Calcutta AND Eastern Canals), which enable Calcutta to tap the trade of the Ganges and Brahmaputra valleys. Regular lines of steamers for passengers and cargo use this route, while the smaller waterways give country boats of all sizes access to almost every part of the tract. Fraserganj at the mouth of the Hooghly river has recently been selected as the site of a permanent wireless telegraphy station, the object of which is to establish communication with vessels in the Bay of Bengal.

Administration

The tracts comprised in the Sundarbans form an integral part of the Districts in which they are included. The revenue work (except its collection) was formerly in the hands of a special officer called the Commissioner in the Sundarbans, who exercised concurrent jurisdic- tion with the District Collectors ; but this appoint- ment has recently been abolished, and the entire revenue administration has been transferred to the Collectors concerned.

The earliest known attempt to bring the Sundarbans under cultiva- tion was that of Khan Jahan. More recent attempts date from 1782, when Mr. Henckell, the first English Judge and Magistrate of Jessore, inaugurated the system of reclamation between Calcutta and the eastern Districts. Henckellganj, named after its founder by his native agent, appears as Hingulganj on the survey maps. This area was then a dense forest, and Mr. Henckell's first step was to clear the jungle ; that done, the lands immediately around the clearances were gradually brought under cultivation. In 1784, when some little experience had been gained, Mr. Henckell submitted a scheme for the reclamation of the Sundarbans, which met with the approval of the Board of Revenue. Two objects were aimed at : to gain a revenue from lands then utterly unproductive, and to obtain a reserve of rice against seasons of drought, the crops in the Sundarbans being very little dependent upon rainfall. The principal measure adopted was to make grants of jungle land on favourable terms to people undertaking to cultivate them. In 1787 Mr. Henckell was appointed Superintendent of the operations for encouraging the reclamation of the Sundarbans, and already at that time 7,000 acres were under cultivation. In the following year, however, disputes arose with the zamlndars who possessed lands adjoining the Sundarbans grants ; and as the zamlndars not only claimed a right to lands cultivated by the holders of these grants, but enforced their claims, the number of settlers began to fall off rapidly. Mr. Henckell expressed a conviction that, if the boundaries of the lands held by the neighbouring zamlndars were settled, the number of grants would at once increase ; but the Board of Revenue had grown lukewarm about the whole scheme, and in 1790 it was practically abandoned. Several of the old grants forthwith relapsed into jungle.

In 1807, however, applications for grants began to come in again ; and in 181 6 the post of Commissioner in the Sundarbans was created by Regulation IX of that year, in order to provide an agency for ascertaining how far neighbouring landholders had encroached be- yond their permanently-settled estates, and for resuming and settling such encroachments. From that time steady progress was made until, in 1872, the total area under cultivation was estimated at 1,087 square miles, of which two-thirds had been reclaimed between 1830 and 1872. The damage done by the disastrous cyclone of 1870 led to the abandonment of many of the more exposed holdings, and in 1882 the total reclaimed area was returned at only 786 square miles. Since then rapid progress has again been made, and in 1904 the total settled area had risen to 2,015 •'square miles.

Settlements of waste lands have, until recently, been formed under the rules promulgated in 1879, the grants made being of two classes: namely, blocks of 200 acres or more leased for forty years to large capitalists who are prepared to spend time and money in developing them ; and plots not exceeding 200 acres leased to small capitalists for clearance by cultivators. Under these rules one-fourth of the entire area leased was for ever exempted from assessment, while the remaining three-fourths was held free of assessment for ten years. On the expiry of the term of the original lease, the lot was open to resettlement for a period of thirty years. It was stipulated that one-eighth of the entire grant should be rendered fit for cultivation at the end of the fifth year, and this condition was enforced either by forfeiture of the grant or by the issue of a fresh lease at enhanced rates. Almost the whole of the area available for settlement in Khulna has already been leased to capitalists ; in Backergunge 479 out of 645 square miles have been settled, and in the Twenty-four Parganas 1,223 out of 2,301 square miles. Experience has shown that this system has led to the growth of an undesirable class of land speculators and middlemen, and to the grinding down of the actual cultivators by excessive rents. Land- jobbers and speculators obtained leases for the purpose of reselling them ; in order to recoup his initial outlay the original lessee often sublet to smaller lessees in return for cash payments ; and the same process was carried on lower down the chain, with the result that the land was eventually reclaimed and cultivated by peasant cultivators paying rack-rents. It was accordingly decided in 1904 to abandon this system and to introduce a system of ryotwAri settlement, as an experimental measure, in the portions of the Sundarbans lying in the Districts of Backergunge and the Twenty-four Parganas. Under this system small areas will be let out to actual cultivators, assistance being given them by Government in the form of advances, as well as by constructing tanks and embankments and clearing the jungle for them.

[J. Westland, Report on Jessore (Calcutta, 1874); F. E. Pargiter, Revenue History of the Sunderbans from 1765 to 1870 (Calcutta, 1885).]

Mauryan era civilisation

The Times of India, Aug 01 2016

Krishnendu Bandyopadhyay Civilisation in Sunderbans traced to Mauryan era

A new archaeological find could rewrite the history of the Sunderbans and set the clock back by more than 20 centuries. Scientists have stumbled upon a cache of remains that indicates the existence of an ancient civilisation in the mangroves dating back to the Mauryan period (322-185 BC). The civilisation, significantly , lasted for the next 500-600 years.

In folklore, the history of the Sunderbans area can be traced back to 200-300 AD. The area was first mapped in 1764 soon after British East India Company obtained proprietary rights from Mughal emperor Alamgir II in 1757. So, the forests may be more than ivory gamesmen, miniature pots, pastel, semiprecious stone beads, net sinkers and pot shards. These have been collected from the Dhanchi and Bijwara forests in the tiger reserve area of Sunderbans over the last 22 years.

Mishra is all praise for fis two millennia older than recorded history .

The exploration at Gobardhanpur in Pathar Pratima block -by a team led by Phanikanta Mishra, regional director (eastern region) of Archaeological Survey of India -is likely to rekindle the long-standing colonial historiography debate that it was the British who made the inaccessible mangroves habitable.

The artefacts include several terracotta human and animal figurines dating back to pre and early centuries of the Christian era, terracotta lumps bearing impressions of seals dating back to the early historical period, terracotta rattles, toys and pendants, herman Biswajit Sahu, who painstakingly pieced together the remains and preserved them at his home. “He knows nothing of archaeology, nor did he know what the Mauryan era meant. But his instinct guided him to preserve these artefacts,“ he said.Sahu has collected more than 15,000 artefacts and continues to collect more during fishing trips to the different islands.

A large number of skeletons, bone fragments, skulls and teeth of wild, domestica ted and aquatic animals are also part of Sahu's collection.All the objects have been kept in a random manner in a recently constructed building.

An analysis of the collections indicates that a wide variety of antiquities date back to the Mauryan era (3rd century BC) and the early centuries of the Christian era.“My preliminary study finds that the civilisation went on from the Mauryan era to the Sunga era and continued through the early Gupta era.It probably ended in the later Gupta era,“ Mishra said.

Mishra is, however, intrigued by the missing link of the civilisation with modern human settlement. “It is a matter of mystery how the civilisation suddenly disappeared. We will study it further.“

Sunderbans now happy hunting ground for tigers

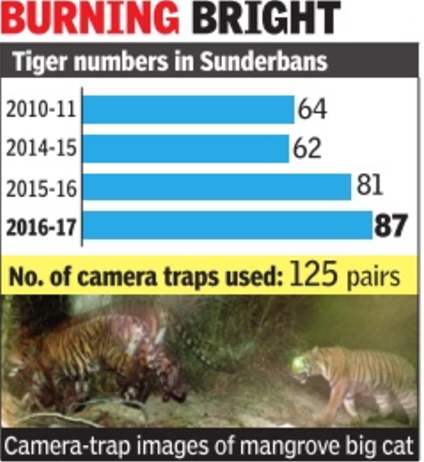

For the second year in a row, tiger population in the Indian Sunderbans has shown an increase. This year, a camera-trap exercise has captured at least six more tigers in the mangroves.

According to a forester associated with the exercise, 87 unique frames were captured by the camera traps in the mangroves, including the tiger reserve area and the South 24Parganas forest division. The count was 81 last year. The latest exercise was conducted between December 2016 and June this year.

Eighty-seven unique frames means the mangroves is home to at least 87 tigers, with the possibility of more big cats being present, said the forester. “It's not possible to photograph all the tigers in a forest,“ he said. While the mean figure is yet to be analysed, officials expect the number to be around 90 this time, compared to last year's 86.

“The trend is positive, but we are still in the process of analysing the final figure that will also be checked by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII),“ said chief wildlife warden Ravi Kant Sinha, adding that the cubs camera-trapped last year have grown up and have probably been photographed again this year. This, according to him, can be a reason behind the positive trend.

Sources revealed that while 62 tigers were photographed in the tiger reserve area -seven more than last year -25 were clicked in the South 24-Parganas division, the forests outside the core area. Pictures of three cubs were also captured, though they were not included in the final figure.

This is the first time that the exercise was conducted by the forest department alone, without the help of any research institute or NGO. A total of 125 pair camera traps were used this year. The camera-trap images are being analysed with the help of a software that matches the stripe patterns of the big cats to arrive at the mean number, a forest department official said.

This exercise is part of the Phase-IV monitoring carried out annually to monitor tiger source populations. This gives reliable estimates of population density , change in numbers over time and key information like survival and recruitment rates.

See also

Sundarbans