Students' unions: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Reforming, curbing student unionism

Bengal, 2017: Ending union raj in universities

Chief minister Mamata Banerjee: another revolutionary policy announced by her government to improve higher education.

West Bengal announced a measure that may include the long lost spirit of enquiry in higher education. The West Bengal Universities and Colleges (Administration and Regulation) Act 2017 will sever the parental influence of political parties on student unions. It will prevent stray uncles and aunties from spaces which they either had to leave or which they could never manage to enter formally.

Here are some measures designed to curb what Didi has realised is “waste of energy“: insignia affiliated to registered political parties will be prohibited on campus; the student union will be renamed student council; election to the student body will be biennial and no longer annual; only students with an attendance of 60% or more will be eligible to vote.

The operation of student wings of political parties in academic institutions is oxymoronic for two reasons. First, higher education entails a pledge to wander in search of wonders. Research and innovation flourish in an environment where the independence to doubt and seek is cherished. Like tentacles of political parties, the presence of student wings on campus is surrender of that freedom.Political parties are too close to authority and wield the power to extend favours.

That student politics is beyond such enticements is to summon the impractical. It is to suggest an impossibility that Kautilya outlined as follows: To put honey on the tongue and not taste it. For instance, SFI university brigade of the CPM has crusaded against the disappearance of Najeeb Ahmed from JNU in 2016. Yet it maintains silence about the equally mysterious disappearance of Manisha Mukherjee from Calcutta University in 1996. The lecturer allegedly fell off the good books of powerful CPM bosses and still remains untraced. SFI cannot act in this case. After all, the leash that powers the bark cannot be stretched much and the hand that feeds can certainly not be bitten.

Second, political groups are now based on myriad interests such as race, caste, art, health, migration and environment. The sheer diversity has made politics a cultural affair subject to constant revision. Entry and exit from political groups change with personal experience and social location. It has ushered what Alberto Melucci has described as nomadic politics.

Political parties Left or Right have strict ideologies with their own scriptures and missionaries. Thus, their nurslings on campus are denied the versatility to celebrate difference. It gives rise to a tyrant army because, as Thomas Aquinas put it, `the dangerous human is not one who is unread but one who has read a single book' or who subscribes to a single perspective.

Now the moot question. Can the Union human resource development minister take the cue from West Bengal and make way for independent student action? Unlikely , because it will go against the `catch them young' strategy .But Mamata has just shown that leaders can tower above the compulsion of numerical politics which is the much overlooked `elephant in the room' of democracy.

The West Bengal BJP unit has not hit the streets against her decision. The 2017 Act is likely to end professional politics on campus and create opportunities for spontaneous collectives. It complements recent decisions that Mamata has taken to improve higher education. Her government has regulated the number of seats across state universities. It has reduced quantity to ensure quality. Her government has also prohibited protests in the higher education hub of Kolkata College Square where vocal chords wrestle with remarkable regularity .

The minister in charge of higher education at the Centre, Javadekar, has initiated unpopular but positive measures too. These include fixation of research seats in universities, launch of university rankings, performance-oriented autonomy and strong signals to marks inflation regimes. The message is clear students must be achievers and not be mollycoddled for votes.

It is obvious that Javadekar must not follow Mamata. In fact, it is expected that the Union minister will mull improved measures. For instance, the appointment of professors as presidents and vice-presidents of student councils is inexplicable in the 2017 Act of West Bengal. It will institute a compliant monitor at the head of a body which must be free to defy and experiment with subversions. Also, departments that have fallen into neglect must be refurbished because they are safe houses for professional politicians on campus.

Such competitive spirit among stateswomen and statesmen to outperform one another could be a great moral engine for the national polity .

The writer is a media professional and doctoral candidate at JNU

Kerala, 2017: HC restricts unions

Like Harvard, many institutions in India, such as Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) are equally known for both their academic rigour and intense political activity . However, a recent Kerala high court judgment challenges this deep and entrenched relationship between education and politics by purporting to ban politics on university campus entirely . The court remarked, “Educational institutions are meant for imparting education and not politics.“

The two judge bench thereby threw the baby out with the bath water.

While being concerned, indeed rightfully so, with increasing violence on university campuses in the name of politics, the judgment attempts to draw no line between critical thinking on the one hand and violent propaganda on the other. No one can and should promote hooliganism, violence, threat and any force of any kind in the name of politics. But one cannot ban a jostling of ideas in public space, a jostling of values, a jostling of individuals who personify the ideas and call for change through debates and discussions.

One cannot ban students from politically organising themselves through student elected bodies and associations. One cannot ban students from questioning the policies at university, city, state, national or international level that affects them and their universe.

More often than not, students are found protesting against university management's autocratic decisions, challenging the nexus between the management and ruling state powers, and challenging vested commercial interests. Students who raise these questions often find themselves being victimised, singled out and made victim of politics by the administration.What is needed is the commitment of university administration to give equal space to different associations to express their views on a variety of topics, rather than trying to muzzle any voice of dissent or lead them towards any particular ideology.

With New Zealand now being led by the country's youngest prime minister in 150 years, Canada being led by Justin Trudeau, its second youngest prime minister ever, and India poised to have the world's largest youth population, this judgment turns the hand of the clock back. While there is clearly a need to regulate money, muscle power and waste in student elections and reconsider some of the Lyngdoh Committee guidelines, banning politics on university campus outright is totally unacceptable.

According to the 2011 census India has a student population of 315 million, big enough to constitute the fourth biggest country in the world. In that context separating education and politics may create a castrated youth who are incapable of understanding, engaging and articulating their views on issues that deeply concern them.

If anything, our political parties should not just pay lip service to the cause of the youth but have a sustained movement to bring more and more youth into the mainstream of electoral politics, by first and foremost encouraging them to vote. By preventing politics on university campus, we are preventing the evolution of thinking beings, restricting their youthful vigour and telling them that their patriotism should be limited to twitterati and paparazzi.

When students think beyond themselves, it's a good thing for democracy.The train of Indian democracy is on the move and it is catching speed. How can India leave its youth behind?

Student politicians who entered state or national politics

From Delhi’s universities, till 2024

Abhinav Rajput, April 16, 2024: The Times of India

From: Abhinav Rajput, April 16, 2024: The Times of India

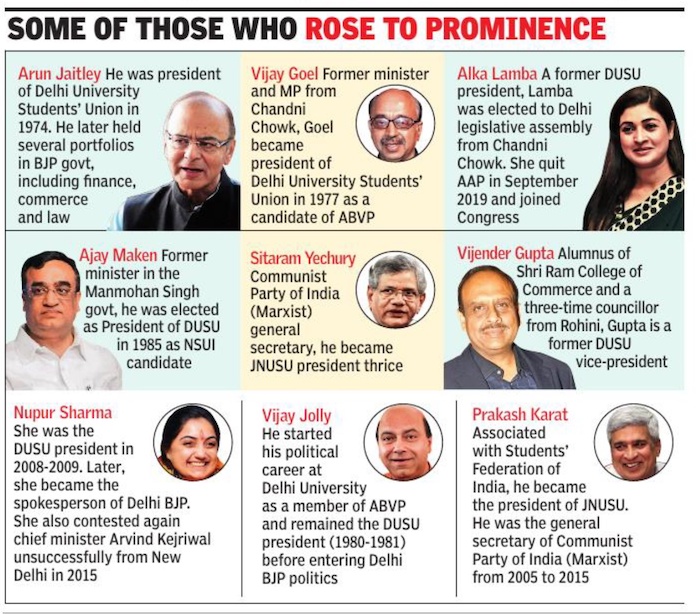

New Delhi: The two premier universities of the capital, Jawaharlal Nehru University and Delhi University, have been cradles for political talent. Many involved in student politics there have risen to prominence in national politics, among them Arun Jaitley, Ajay Maken, Prakash Karat, Sitaram Yechury and DP Tripathi. Former JNU Students’ Union president Kanhaiya Kumar’s candidature in North East Delhi marks yet another chapter in this tradition.

Jaitley, an influential BJP leader and minister, was president of Delhi University Students’ Union in 1974. He later took charge of such important ministries as finance, commerce and law in BJP-led central govts. Ajay Maken too began his political career with DUSU, becoming its president in 1985 as a National Students' Union of India member.

Vijay Jolly, a member of ABVP, served as DUSU president in 1980 before stepping into state politics with BJP. “With people who start their career in student politics, there is a greater ideological commitment. You will not see them shifting to other parties,” Jolly contended. “When one leaves student politics, one does so with a good education, a positive outlook and a commitment to work for change in society.”

The former BJP Union minister added, “You will also see they are innovative in terms of campaign designing because they have had to innovate at the college level. But then, they must have the knack to feel the pulse of the nation to succeed in politics.”

Another student leader who successfully progressed from ABVP to make the cut on the bigger stage was former Chandni Chowk MP and minister Vijay Goel, who led DUSU in 1977. An alumnus of Shri Ram College of Commerce and a three-time municipal coun- cillor from Rohini, started as secretary of Janta Vidyarthi Morcha in 1980 with an elevation to joint convenorship three years later before he joined ABVP. “Student politics gives you a better vision because you need to interact with people from all states. You become aware of the country’s diversity and broaden your views,” said Goel. “Students leaders are also accommodating about different views and ideologies because they have to engage in protests against the system.”

Congress too has seen leaders who cut their teeth in student politics in its fold. Alka Lamba, an NSUI member who became DUSU president, was elected to the Delhi Assembly from Chandni Chowk in 2015. Lamba said, “What sets a student leader apart from others is that they understand the aspirations and ambitions of the youth better. The young and first-time voters are very important to every political party. In university and college, we become aware of their expectations from the political dispensation.” JNU has given several veterans to the political landscape, including two left stalwarts, Karat and Yechury. Karat was involved with student politics and was elected the third president of JNUSU. He was also the second president of the Students’ Federation of India, the CPIM’s student wing, between 1974 and 1979. He worked underground for one and a half years during the Emergency.

Yechury too went underground for some time in 1975 while a student at JNU, organising resistance to the Emergency before his arrest. After the Emergency, he was elected president of JNUSU three times.