Somnath Chatterjee

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A brief biography

Expulsion row dogs Somnath’s last trip, August 14, 2018: The Times of India

From: Expulsion row dogs Somnath’s last trip, August 14, 2018: The Times of India

Bitter Family Shuns CPM Leaders

Somnath Chatterjee, the erstwhile Left Front regime’s first pro-business and pro-industry face from an era when very few CPM leaders would want to be seen in the company of either a businessman or an industrialist, passed away at a Kolkata hospital on Monday. He was 89.

Chatterjee, the liberal and the pragmatist in a party full of dogmatic conservatives, was a CPM member for four decades. But the contradictions between the party and the man proved too much and it was perhaps predestined that CPM would finally show him the door (in 2008). It was also perhaps no surprise that the forced orphanhood — and not the 10 terms that he served the party in the Lok Sabha — would become the talking point on the day he died.

Less than 10 hours after Chatterjee breathed his last, his family — son and daughter — spoke bitterly about how they felt let down by the treatment meted out to their father by the CPM even in his death. The CPM politburo communique, an Orwellian relic from communist Russia, might have contributed to the bereaved family’s bitterness. “An eminent lawyer by profession, he (Chatterjee) also took up the cause of

the working class,” it read, eschewing any reference to his association with the party.

Chatterjee’s political career saw not one but two watersheds. The first came in 1984, amid the Indira Gandhi sympathy tsunami for Congress, when he was defeated by a 20-something, unheralded Mamata Banerjee in the then CPM bastion of Jadavpur. But the second was a more permanent low-water mark for both Chatterjee and CPM. It came in 2008, when he was turned out by his party for refusing to heed its diktat asking him to get off the Lok Sabha Speaker’s chair.

By then, his biggest backer in the party — former Bengal CM Jyoti Basu — had become entirely home-bound. Chatterjee also made the mistake of daring to go where even his mentor did not venture. Basu, asked by CPM to stay away from the PM’s race in the mid-1990s, came up with a telling one-liner on his party’s folly; he called it a “historic blunder” but toed the party line nevertheless. More than 10 years later, Chatterjee had no such telling one-liner to describe his party’s folly; but he stayed put in the Speaker’s chair, prompting his party to disown him. That orphanhood rankled. “I wanted to remain with the party till my last. It is the party that showed me the door,” he had said then.

Chatterjee was unwell for some time, spending most of his last two months at Belle Vue Clinic. He spent a 40-day stretch at the hospital after a brain stroke, returned home for a few days in July-end and then again entered the hospital — for the last time, as it turned out — last Tuesday. His vital organs were giving away gradually and he suffered a massive cardiac arrest last Thursday, following which he was put on ventilation, and a milder one on Sunday; he did not survive these two attacks.

B

From: Suman Chattopadhyay, He was more a Bengali bhadralok than a copybook communist ideologue, August 14, 2018: The Times of India

Soon after his election as the 13th Lok Sabha Speaker in June 2004, Somnath Chatterjee received a call from then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Customary congratulations over, the PM heaved a sigh of relief and told him, “I will now be able to sleep peacefully at night.”

Four years later when the CPMled Left parties decided to withdraw support to the first UPA government following bitter wrangling over the Indo-US nuclear deal, Somnath, the quintessential constitutionalist-parliamentarian defied the party whip to uphold the noble traditions of parliamentary democracy. In retaliation, the party expelled him from its primary membership invoking an article and clause of the party constitution that denied a member even his right to self-defence.

An emotion-choked Somnathbabu described it as “one of the saddest days of my life’’. He promptly announced his retirement from a fourdecade-long political life to settle near Rabindranath Tagore’s abode Shantiniketan in Bolpur, his erstwhile parliamentary constituency that had returned him seven times consecutively to Parliament. Having severed the umbilical cord with CPM and politics, he settled for a quiet, dignified retired life, revelling in Tagore’s memory and creations, also working for the welfare of the grassroots faithful, mostly the local Santhal tribe, rural women and the marginalised. As the news of his death reached them, they felt truly orphaned.

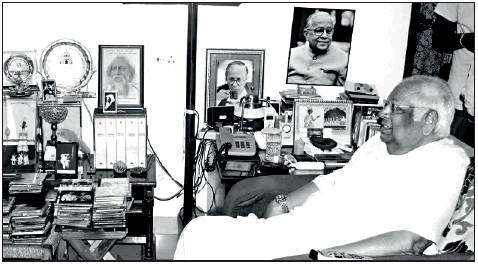

Even when Somnathbabu was in active politics, the walls of his spartan Kolkata home always had two frames of two of his life-long icons — Tagore and Jyoti Basu. No Vladimir Lenin, no Karl Marx, no Friedrich Engels, the standard legends of the Marxist pantheon. The choice unmistakably demonstrated the man with an independent mind whose real identity was more of a thoroughly cultured, educated Bengali ‘bhadrolok’ than of a copybook, dogma-driven communist ideologue. Somnath Chatterjee, it will not be too far fetched to assume, was more of an ‘outsider’ in a regimented, claustrophobic political outfit like CPM.

More than the party and its pursuit of puritan politics, he owed his personal allegiance to Jyoti Basu, who had been his constant friend, guide and philosopher. Basu brought him to the party fold in the late 1960s even though Somnath’s father NC Chatterjee had once been the president of the Hindu Mahasabha, and one of the closest associates of Shyama Prasad Mukherjee. It was at Basu’s behest that he was made a central committee member in the early 1990s long after many of his junior state comrades made it to the highest decision making body of the party.

Finally at the most defining moment of his political career during the no-confidence debate in 2008, Somnath came down to Kolkata to consult his mentor and seek his blessings. As his memoir ‘Keeping the Faith, Memoirs of a Parliamentarian’ reveals, Basu too found merit in his arguments that the Speaker need not be subjugated to party lines inside Parliament. It is another matter that even Basu’s support could not save Somnathbabu from his party’s wrath. In Prakash Karat’s estimation, both Basu and Chatterjee were then found expendable.

A legal luminary of extraordinary talent and acumen, Somnathbabu’s baritone voice, sharp repartees and arguments laced with an acute sense of wit and humour distinguished him from the rut in Parliament. His brutally frank tongue and occasional outbursts of sentiments sometimes landed him in avoidable embarrassment but he bore malice towards none, not even Mamata Banerjee, who was responsible for his only electoral defeat in his long and spectacular parliamentary innings.

An unconventional Leftist, Somnathbabu was also a scrupulously honest person, almost an endangered species in today’s political theatre. When he took up the Speaker’s official residence at 20 Akbar Road, he discovered that the norm was that tea, biscuits, phenyl and soap bills were paid from Lok Sabha accounts. He stopped the practice forthwith saying, “I think I can afford my bathroom expenses as also a cup of tea for my guests.’’ Today as his mortal remains lay in state on the state assembly premises, Somnathbabu’s one time bête noire Mamata Banerjee was seen in complete charge while his wife did not allow his former party comrades to lay the red-coloured party flag over his body. His family did not even allow his body to be taken to the state party headquarters. What a poignant dramatic twist to the tale at the end of the man’s long, colourful, eventful and memorable journey.