Raghuram Rajan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A profile

A

As the RBI Governor

Through tight monetary measures, he contained inflation, with consumer price inflation falling to an all-time low of 6.46 per cent and the wholesale price index easing to a five-year low of 2.38 per cent in September 2014.

He successfully tackled India's currency crisis, rescuing the rupee from its historic low of 68.83 against the dollar in August 2013 to 61.7 as on November 7, 2014.

He won the Director's Gold Medal at IIT-Delhi and was a gold medallist at IIM-Ahmedabad. He was given the Central Bank Governor of the Year 2014 award by Euromoney magazine for stabilising the rupee.

Seeking support : “I seek the blessings of all citizens of India.May they give me the courage and highest stride.”

Bouncing back : He said, “I think over the course of this year, we will be solidly in the 5 per cent growth range and by next year we should be in the 6 per cent range.”

B

Engineer-turned economist with a rockstar’s appeal

Surojit Gupta & Sidhartha | TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/07

Rated by peers across the world as one of the most influential economists of his generation, Rajan, 50, is among the youngest RBI governors (PM Manmohan Singh took charge when he was 10 days short of his 50th birthday). Rajan was the youngest-ever — also the first non-westerner — chief economist of the IMF, from 2003 to 2006. In 2005, he predicted the financial crisis of 2008-09, but was brushed aside by economists such as former US treasury secretary and Harvard University president Lawrence Summers, who called him a “Luddite”.

The Bhopal-born son of a bureaucrat has always been a high achiever: a gold medalist at both IIT Delhi and IIM Ahmedabad, he completed his PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Traditionally, the chief economic advisor, a professional economist in a sea of bureaucrats, sat in one corner of the North Block. But weeks after taking charge as the government’s chief economist, Raghuram Rajan moved into a fi rst floor room, adjacent to finance minister P Chidambaram’s, signalling a shift in power equations.

In the year that Rajan has spent on Raisina Hill, he gained in stature and enjoyed the confidence that few of his predecessors enjoyed. From being an economist focused on banking and finance, Raghu, as colleagues call him, was slowly initiated into complex issues dealing with the political economy in a chaotic democracy.

His detractors, skeptical that he lacked administrative experience, were silenced when Rajan joined hands with his boss to mend the economy.

Even when it came to deciding on a key political demand from states such as Bihar and West Bengal for special category status and a debt recast, Chidambaram leaned on the 50-yearold Raghu to find a way out. Before he shifts to Mumbai’s Mint Road, Rajan would’ve finalized the contours of a possible policy change, based on a soon-to-be ready development index against the current system of gauging states on the basis of geography.

When it came to core issues, the government invariably turned to the engineerturned-economist. The sharp slide in the rupee prompted the government to draft Rajan in as one of the main firefighters to draw up a plan to increase dollar inflows. Unlike the hush-hush way in which decisions were taken in the past, Rajan invited private and foreign bankers to North Block to stitch up a plan to navigate the rupee out of choppy waters. Based on his inputs, the government announced its intent to go for quasisovereign bonds, without ruling out the possibility of India’s first sovereign fund-raising. Be it calming the jittery markets or over-enthusiastic reporters, he used all his charm and intellect, sometimes switching to Hindi. His rockstar appeal attracted a swarm of eager listeners wherever he was listed to speak.

Picking up from where his predecessor left, Rajan moved to reshape the dowdy Economic Survey that is tabled a day ahead of the Union Budget. Drafting many young economists in the Economic Division, he ensured new thoughts run through the pages of the economic report card. And, he will leave his imprint behind with a quarterly update.

As Governor, RBI

Contributions as the Governor, RBI

The Times of India, Aug 21 2016

Mayur Shetty

Raghuram Rajan described himself as “fundamentally an academic“ with the governorship of RBI being a “side job“. Perhaps true considering that his threeyear term at the RBI was the shortest for any governor after liberalization in 1991 and might be just a blip in Rajan's career.Tenure notwithstanding, the youngest governor at the RBI will leave behind a legacy disproportionate to his tenure. Most of the headlines that Rajan drew were because of his standing as a public intellectual.He broke the mould of a technocrat as someone who does not make public pronouncements on issues outside his domain. Some saw this as ambition to play a larger role, but his explanation was that these issues like intolerance and crony capitalism were endemic to growth. Rajan was not just a free thinker but with such a personality that it was impossible for him not to air his thoughts.

Rajan wanted the governorship to execute his ideas. The job gave him an opportunity to implement reforms that he had suggested as a consultant to the Indian government in 2008. Most of the banking reforms being implemented today can be traced to a report A Hundred Small Steps submitted by Rajan when he was a 45-year-old professor from University of Chicago after he was appointed consultant by the United Progressive Alliance government. The report pitched for steps like inflation-targeting, broadening bond markets and stronger boards for government banks. For central bank watchers, the success of an incumbent in stabilizing the exchange rate, taming inflation and cleaning up banks would be considered a fair measure of success. But Rajan's legacy goes beyond these issues of macro stability .

He is likely to be remembered for a number of things that he has institutionalized. Since his appointment in 2013 was for a threeyear tenure, Rajan set a three-year time-frame to achieve his agenda which included bringing competition and innovation in banking, cleaning up bank balance sheets, creating a new monetary policy framework, and developing a structure for faster transmission of interest rates to borrowers.

The end of Rajan's tenure coincides with the end of monetary decision-making by the office of the governor. Rajan has successfully pushed for a new monetary policy framework, where interest rates will be decided by a committee rather than a governor. If the new framework functions along expected lines, markets can look forward to seeing a more predictable and stable rate policy which will help develop bond markets.

Monthly Rate Revision: Borrowers can thank Rajan as interest rates on their loans begin to come down every month and not only when banks revise rates.This is possible because of Rajan's decision in December 2015 to take away from banks the freedom to decide when to revise rates. As of now most borrowers have their loans pegged to the earlier benchmark the base rate. According to the RBI, rates will have to be decided based on the “marginal cost of funds“. In other words, banks have to routinely calculate their cost of funds and any change has to be passed on to borrowers by revising their benchmark. This new formula-based benchmark is called the marginal cost of lending rate (MCLR). Once most borrowers migrate to the MCLR regime, rates would begin to come down every month.

Let A Thousand Flowers Bloom: Rajan's most understated achievement has been the big jump in innovation in financial services. Before Rajan took charge, a private bank had put up a proposal to the RBI to allow cardless withdrawal from ATMs based on an SMS code generated on the request of the cardholder.The RBI was wary of the service fearing that it would be misused.Rajan, however, was excited about the new solution which he saw as a remittance tool. According to Rajan, a “cash out“ facility was crucial for remittances because there is a large recipient population in the country without access to formal banking. “The system will take care of necessary safeguards of customer identification, transaction validation, and velocity checks. We need more such innovative products, some of which mobile companies are providing,“ Rajan said in a Nasscom speech in 2014.

Payments Bank Licence: For years banks had been struggling to use the last-mile connectivity that mobile telecom companies had built. Banks were keen to use the mobile company's recharge networks in rural areas as banking correspondents. They also wanted to reach out to unbanked customers of mobile companies.But mobile companies wanted to be in the game themselves. Regulators were, however, wary of granting full banking licences to telcos as they were either owned by foreigners or part of conglomerates. Rajan's proposals allowed telcos to set up payments banks which could provide transactional facilities like remittances and payments but could not extend loans. This addressed RBI's concerns of corporate banks engaging in self-serving. It also enabled existing banks to partner payment banks to sell their products.

Small Finance Bank Licences: Likewise in the case of microfinance companies, the RBI addressed the issue of microfinance regulation by allowing some of them to convert into banks. While announcing the guidelines, Rajan clarified that the “small“ in the title referred to the size of the loans and not to the size of the banks. He said that these small finance banks could grow into giant institutions. This was the key difference between the earlier approach to small business lending and the one taken by Rajan. Earlier local area banks and regional rural banks could not make a dent as their mandate was regional and successful players could not grow beyond a point. After taking charge, Rajan did not waste any time in initiating the reform process.

2016: Quits after 1st term

The Times of India, Jun 19 2016

Surojit Gupta

His name was Rajan and he left India shaken & stirred

He steadied the country's choppy financial markets, pulled no punches when he delivered his speeches and endeared himself to even those who have nothing to do with the staid world of monetary policy. Raghuram Govind Rajan, engineer-turned economist, will go down as perhaps the most flamboyant and outspoken Reserve Bank governors that India has ever seen.

In the nearly three years that he has occupied the 18th floor of fice of the RBI building on Mint Street in Mumbai, Rajan has taken several steps to modernize the country's central bank.

Along the way he has earned several nicknames “Rockstar“, “the Guv“ and his speeches and press conferences have been tracked like the twists and turns of a T-20 cricket match.

Such was his charm that young girls chased him for selfies and columnists penned articles titled `The Unbearable Hotness of Being Raghuram Rajan'.Even the Financial Times waxed on about his squash and tennis honed physique while Shobhaa De pointed out that “it's not often that one gets an RBI Guv who makes hearts (not just female ones) go dhak dhak each time he strides into a room.“ He took office at a time when the foreign exchange market was caught in the storm sweeping the globe. But he quickly steadied the ship which prompted some to compare him with the legendary spymaster James Bond. After all, he did famously declare, “My name is Rajan and I do what I do“.

The former International Monetary Fund (IMF) chief economist was also vocal about the need for tolerance after the Dadri incident, the government's Make in India initiative and the scorching growth rate which the government has been showcasing as one its key achievements. His statement comparing the Indian economy with `a one-eyed king in a blind world' made headlines.

Rajan, who figured in the Time magazine's list of 100 most influential people in the world, attracted criticism from sections of the Narendra Modi government for his reluctance to cut interest rates. For him economic logic was above populism as he pointed to the lurking inflationary pressures.

Reams of newsprint were devoted to his reappointment, and thousands went on to sign online petitions demanding a second term for him.

As an economist

2017: On the Nobel shortlist

October 7, 2017: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Rajan among six economists on the list of probable winners compiled by Clarivate Analytics

Rajan is considered a candidate for his "contributions illuminating the dimensions of decisions in corporate finance"

Former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan features in the list of probables for this year's Nobel Prize in Economics, The Wall Street Journal has reported.

He is one of the six economists on the list of probable winners compiled by Clarivate Analytics, a company that does academic and scientific research and maintains a list of dozens of possible Nobel Prize winners based on research citations.

The entry to the list does not guarantee that Rajan is a front-runner but he is a probable who stands a chance to win. Rajan, whose three year term as Reserve Bank Governor ended on September 4, 2016+ , is considered a candidate for his "contributions illuminating the dimensions of decisions in corporate finance", Clarivate said.

According to Clarivate Analytics, the list of possible Nobel Prize winners based on research citations include Colin Camerer of the California Institute of Technology and George Loewenstein of Carnegie Mellon University (for pioneering research in behavioural economics and in neuroeconomics); Robert Hall of Stanford University (for his analysis of worker productivity and studies of recessions and unemployment); and Michael Jensen of Harvard, Stewart Myers of MIT and Raghuram Rajan of the University of Chicago (for their contributions illuminating the dimensions of decisions in corporate finance).

Rajan, who at 40 was the first non-western and the youngest to become the chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, shot to big fame three years after he predicted a financial crisis at an annual gathering of economists and bankers in the US in 2005.

He was appointed RBI Governor by the UPA government in 2013 and although he wanted a second term he was not offered an extension, which most of his predecessors got, by the NDA regime.

He is currently the Katherine Dusak Miller Distinguished Service Professor of Finance at the Booth School of Business, University of Chicago.

Nobel laureate Thaler on Rajan

Shailaja Neelakantan, October 11, 2017: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Rajan returned to academics, to the University of Chicago, after his 3-year term as RBI governor ended in September 2016

More than happy to have "Raghu" back, was none other than future Nobel winner Richard Thaler.

And Thaler went so far as to say that Rajan's return to Chicago was actually "India's loss".

Former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan's term at the central bank wasn't extended+ by the Centre last year, but there was one person who sure was happy about that - Richard Thaler. Yes, the same Thaler who earlier this week was named the Nobel Prize winner in Economics+ for 2017. Thaler and Rajan have been and still are colleagues at the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business.

Rajan took a leave of absence from Booth to serve as RBI governor. When his three-year term as head of India's central bank ended - or rather, wasn't renewed - in September last year, Rajan announced that he was returning to academics. Upon his announcement, Booth School tweeted:

More than happy to have "Raghu" back, was none other than future Nobel winner Thaler. And he said Rajan's return was actually "India's loss".

It is by now well known that Rajan is widely credited with having anticipated the 2008 global financial meltdown some years before it happened. PTI reported that Rajan is the first RBI governor since 1992 to have not been appointed for a five-year term.

When Rajan announced his return to Booth, there was some speculation that he didn't stay on as RBI governor because the University of Chicago wouldn't extend his leave of absence. 'Not true,' said Rajan at the time.

In fact, he said, he wanted to stay on as RBI governor, to complete the unfinished task he initiated of cleaning up banks. But there was no proposal from the government that he continue beyond his 3-year term, he said.

"So that (bank clean-up) was primary reason that I was open (to staying on) but we didn't get to a point where there was, as I said, a contract on the table," said Rajan to PTI. Rajan, who was appointed to the RBI by the previous UPA government, had several run-ins with the current dispensation over differences in policy. The former RBI governor was also critical of the Centre's November 8 note ban+ .

"Although there may be long-term benefits, I felt the likely short-term economic costs would outweigh them, and felt there were potentially better alternatives to achieve the main goals," he wrote in his book 'I do what I do', which was released last month. "I made these views known in no uncertain terms."

Legacy

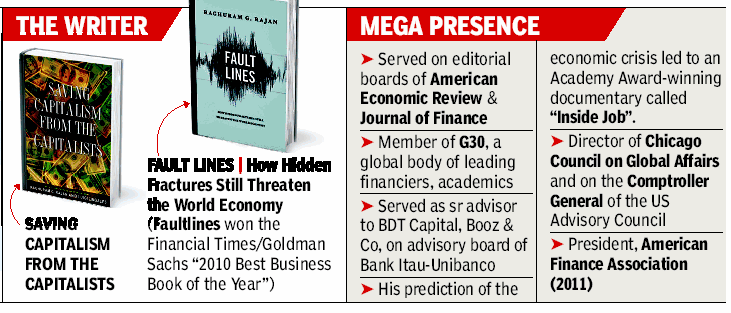

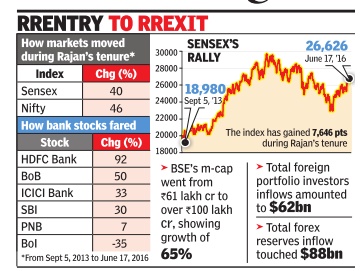

See graphics:

Raghuram Rajan: Legacy

Raghuram Rajan: achievements and criticism

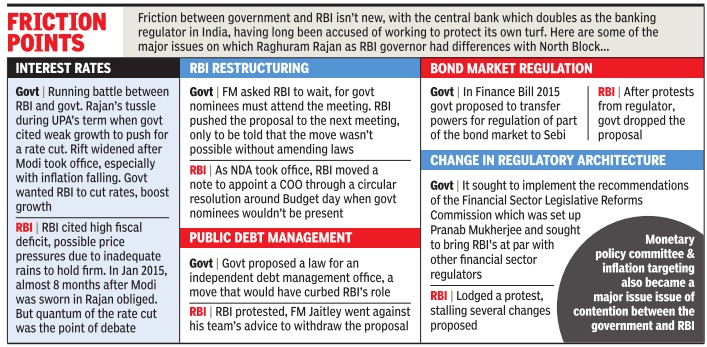

RBI and the government

The Times of India, Jun 20 2016

Sense of unease lurked below surface The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the government may not have gone public with their differences in recent months, but there were several issues which divided them and finally resulted in Raghuram Rajan's decision to rule himself out for a second term. During the initial months of the NDA regime, there had been occasions when government functionaries had spoken about the need to cut interest rates to prod the central bank. This made way for several exchanges on key issues -ranging from a monetary policy panel and the inflation target to managing government borrowings -where some strong words were used.

While things seemed to have settled down, at least on the surface, the government was not completely at ease with the way the RBI under Rajan had dealt with several issues and remained dissatisfied with the pace of interest rate reduction, slow growth in lending and stress in the small and medium scale sector.

There is a strong view in the government that the RBI has been “behind the curve“ in reducing interest rates and this has hurt the SME sector and higher rates were more beneficial to foreign institutional investors rather than the domestic market.

The sluggish growth in lending has been a serious concern for the government as it frets over inadequate private investment and is trying to get the economy moving through higher public spending to make up for low capital expenditure by India Inc.

Rajan's frequent pronouncements on a range of issues from the intolerance debate to the comments on India being a “one-eyed king in the land of the blind“ did get the government's goat though it chose to hold its breath on most provocations.

A former RBI governor felt Rajan's comments on issues not related to his remit were a transgression of norms that guide the office. Others, however, felt that while he has pushed the limits, his standing made him eligible to speak on domestic and international developments. His stature helped India, rather than impede it.

What did bother Rajan, it would seem, was the lack of outright condemnation of Rajya Sabha MP Subramanian Swamy's diatribes, accusing the RBI governor of extraterritorial loyalities and of leaking official communication.

The decision that a cabi secretary-headed committee will shortlist candidates for the RBI governor's post and will examine possible choices, including the incumbent, went down poorly at the central bank. In the past, such a decision was essentially taken by Prime Ministers, sometimes in consultation with finance ministers.

Earlier, the process for the selection of the RBI deputy governor was also changed.Previously , the RBI governor headed the selection process, but this time around he was a member of the committee headed by the cabinet secretary .The government maintains the financial sector regulatory appointment search committee (FSRASC) was set up some time back in accordance with the recommendation of previous panels.

There is also an impression that the governor's “star status“ did not find adequate resonance in the government. The tendency in the government has been to see the RBI as part of the team that is involved in the management of the economy .

Reforms

The Times of India, Jun 20 2016

Rajan's `100 small steps' basis for big bank reforms

Mayur Shetty

In the absence of any explanation from the RBI governor or the government, Raghuram Rajan's decision to walk away from a second term is widely seen to be triggered by differences between the two. But this is ironic considering that the genesis of most of the Narendra Modi government's banking reforms is a 2008 report authored by Rajan. Also, Rajan has done more to iron out the historical differences between the central bank and the government, which reached its peak under his predecessor D Subbarao, and created a framework where both would work together on policy .

In the hype surrounding the announcement of the `Indradhanush' reforms in public sector banking, what seems to have been lost is origin of most of the measures.

The reform road map for the public sector banks (PSBs) includes proposals such as a holding company for PSU banks, strengthening of bank boards, privatization of small PSBs, the push on financial inclusion and inflation targeting by the central bank. Incidentally , all of The only possible area of difference that appears to be left behind is Rajan's freethinking approach to communication. Comments on issues such as tolerance which had taken a political dimension appear to have made many in the finance ministry uncomfortable. Also, Rajan's decision to force banks into classifying loans as being in default was seen by many as an adversarial stance aimed at forcing the government to take some decisions.

As to the purported differences between the governor and the government on interest rates, none of that is new . Former RBI governor D Subbarao had sparred with both the finance ministers during his term -Pranab Mukherjee and P Chidambaram. The differences spilled over to public discourse as well and made its way into Subbarao's last speech. Rajan's term, if anything, has helped bridge the gap by agreeing to a monetary policy framework where RBI members and government nominees would have equal say . The reports of the technical advisory committee indicate that the external members are less hawkish on interest rates. In the past, even the top rung of RBI did not speak in one voice on interest rates with former deputy governor Subir Gokarn sending different signals from the governor.

There was also media speculation that the government's decision to have a panel headed by a bureaucrat irked the governor. According to sources in the RBI, the government always had its own views on appointing a deputy governor. Former governor D Subbarao is understood to have made a strong pitch for a second term for both his deputies -Subir Gokarn and Usha Thorat.