Pandit Ravi Shankar

At present, this article is (temporarily) only about Pandit Ravi Shankar and the Grammies. It is only a fragment of the ultimate article which, it is hoped, readers will expand it to after Indpaedia is thrown open to all readers.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The sources of this article are…

Amita Nair, Ravikanth3 [1]<>Amann Khuranaa ‘‘The Times of India’’

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A brief biography

From: Gowri Ramnarayan, Remembering the man who took Indian music to the West, October 19, 2020: The Times of India

From: Gowri Ramnarayan, Remembering the man who took Indian music to the West, October 19, 2020: The Times of India

From: Gowri Ramnarayan, Remembering the man who took Indian music to the West, October 19, 2020: The Times of India

From: Gowri Ramnarayan, Remembering the man who took Indian music to the West, October 19, 2020: The Times of India

From: Gowri Ramnarayan, Remembering the man who took Indian music to the West, October 19, 2020: The Times of India

From: Gowri Ramnarayan, Remembering the man who took Indian music to the West, October 19, 2020: The Times of India

Young Ravi could have no memories of this viral scourge. He faced other unsettling experiences — a father abandoning the family, his single mother raising her sons on slender means, transposition at age nine from hallowed Banaras to haut monde Paris, where he saw “too much, too soon.” Hectic performance tours and revels with the glitterati of the western world were part of the routine for the boy who became an acclaimed dancer in his brother’s Indian ballets.

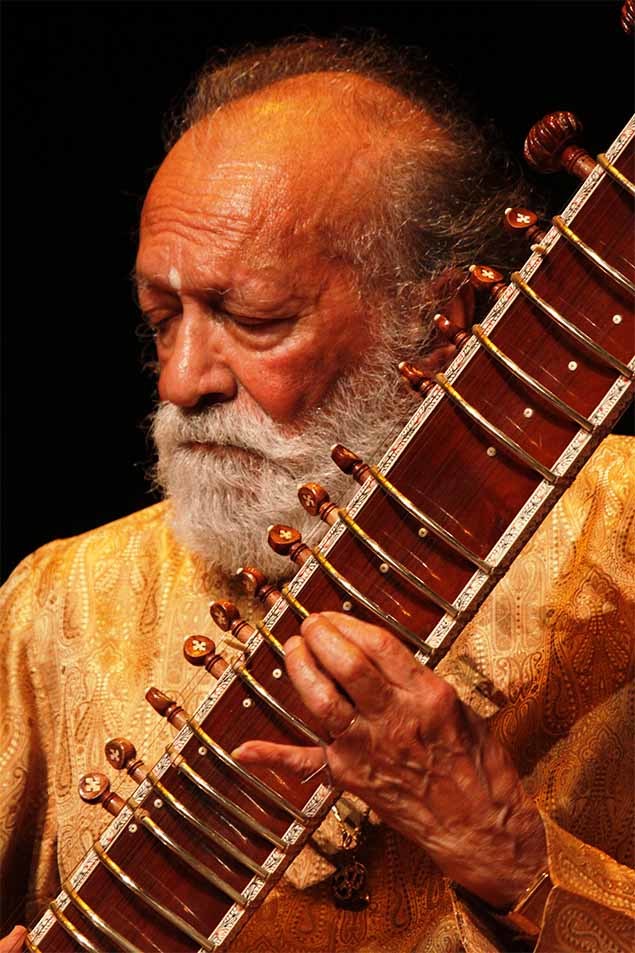

Why did the boy suddenly give up glitz and fame to seek his soul in the sitar? Surrender to a martinet guru Allauddin Khan in a small town in India? “When I was a child, my mother called me ‘chanchal’, restless, my guru called me butterfly. I’ve tried to harness that restlessness in my search for the highest experience. Shanti!” And did he find that serenity in music? Once the maestro gave a dour hint. “Listeners said they found my music meditative, blissful, even healing. Maybe an artist has to go through hell to create heaven for others.” Independent India fostered multi-directional cultural growth. Ravi Shankar composed pathbreaking music for theatre (IPTA), films (Satyajit Ray’s ‘Pather Panchali’), directed music for All India Radio, innovated Indian orchestral scores, created spectacular ballets like ‘Discovery of India’, based on Jawaharlal Nehru’s book. He continued to be driven by contrapuntal movements, charged with conflict, contrast and friction. Longing to be a classicist, he crossed boundaries. Not Oscar-winning ‘Gandhi’, but Canadian farce ‘A Chairy Tale’ gave him the greatest thrill to score. Why? “I made high serious Indian classical music produce hilarious comic effects!”

When the world knew little, cared less, and mostly misunderstood Indian music, Ravi Shankar put India on the world map and paved the way for fellow artists to follow. To change the westerners’ view of Indian music – “dull, monotonous, grating… lacking in modulation, harmony and counterpoint” – he evolved classy visual settings, crisp introductions and riveting methods of presentation. They invited bad press at home back then but remain models of their kind even today. Encounters with two vastly different cult figures fulfilled his dream. Classical violinist Yehudi Menuhin, friend and collaborator, exclaimed, “I was terrified to play with Ravi. I felt I was in no way worthy.” Later, flautist Jean Paul Rampal, conductor Andre Previn and modern composer Philip Glass were to feel privileged to work on the original music Shankar composed. Fortuitously, Beatle George Harrison forged a long term bond with Ravi Shankar when he took lessons from the sitarist, made albums and toured with him, edited and introduced his guru’s autobiography.

We know just how Harrison’s off-key sitar-strumming (Norwegian Wood, 1965) catapulted Ravi Shankar into the psychedelic zone, to be idolised by thousands of hippies in Monterey and Woodstock. Characteristically, he registered mixed feelings about playing for flower children who smoked, snorted, masturbated, copulated as he played; was horrified at Jimi Hendricks burning his guitar on stage; frustrated at being unable to break his contract. But he was not impervious to the heady thrill of superstardom. Vitriolic criticism in India for “polluting” tradition to pander to the west proved hurtful. Rivalry with fellow sitar artist Vilayat Khan added bitterness, especially as the ustad trailed a hoary family pedigree in music (as the pandit did not), and was hailed by some cognoscenti as a musicians’ musician.

But the lifelong tug-of-war was between flesh and spirit. The sybarite wanted to be a sanyasi. He found godmen — Tat Baba to Sai Baba — as irresistible as women. Numerous liaisons followed his early break-up with his first wife, until a late second marriage to Sukanya Rajan gave the aging artist the strength and comfort he needed. There were areas of silence — his father’s mysterious murder, early sexual abuse, his troubled relationship with son Shubho, and the latter’s untimely death. When he passed away at age 92, the global icon may not have been “calm of mind, all passion spent”. But he had come to terms with tumults, triumphs and tragedies. “ Man mein prem shanti bhar deejiye (heart filled with love and peace)” was what he prayed for. Peace comes with acceptance. Didn’t Ravi Shankar once say, “If I could live my life over again, I will focus on the purely classical approach, go deep, not stretch myself out in all directions… But again, maybe not! I am ‘ chanchal’, not ‘ shaant’. I have to be myself. Ravi means the sun. I have to be my own Sun, not reflect some other light.”

Today, as the world reels under the impact of a deadly virus, listening to the master spinning a magnificent Raag Parameshwari can transport listeners to the ghats of Banaras where a young boy watches the sunrise. Mantras resound, bells ring, conches blow. The Ganga flows on. And in his music, “Ravi” continues to rise above mist, flame and smoke, through sickness and despair, beaming rejuvenating hope to heal the world.

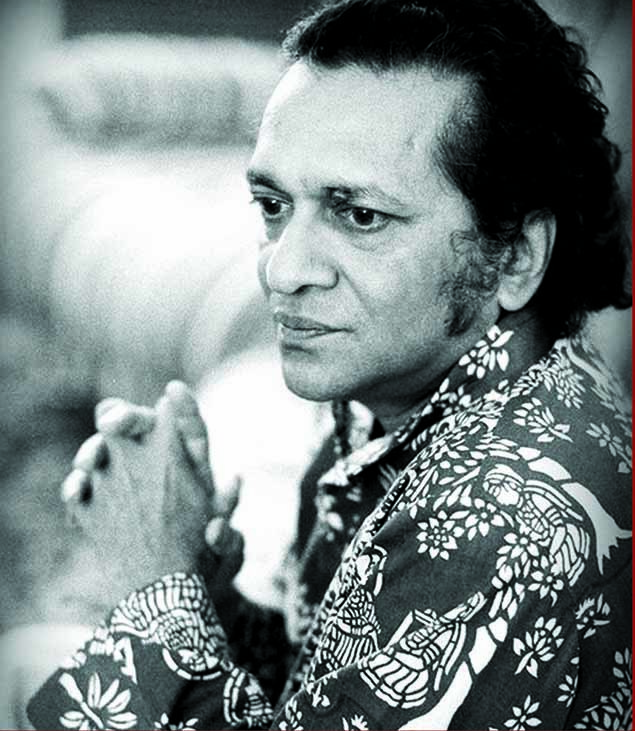

Pandit Ravi Shankar: 1920-2012 (Pic courtesy: Shankar Ramachandran)

THE MAESTRO'S JOURNEY

April 7, 1920 | Born in Banaras to a Bengali family, his brother Uday took him to Paris at the age of 10 as part of his dance troupe

1934 | Met Allaudin Khan. Four years later, he went to Maihar to study sitar under Khan

1944 | After his sitar training , began working for the Indian People’s Theatre Association, composing music for ballets in Mumbai. Turned music director for All-India Radio

Wrote the score for Satyajit Ray’s celebrated The Apu Trilogy

1966 | George Harrison began studying sitar with Ravi Shankar

1969 | Performed at the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock

1982 | Got an Oscar nomination for his score for Richard Attenborough’s ‘Gandhi’

Won three Grammy Awards (two posthumous)

2012 | Died in California on December 11 at the age of 92

(The writer is a playwright and musician)

Grammy awards

1967: Sitar maestro Pandit Ravi Shankar became the first Indian to receive a Grammy. This was for his contribution to West Meets East with violinist Yehudi Menuhin. Category: Best Chamber Music Performance

1972: Pandit Ravi Shankar got his second Grammy for The Concert for Bangladesh featuring him, George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Leon Russell, Ringo Starr, Billy Preston, Eric Clapton and Klaus Voormann. The Concert for Bangladesh was also named Album of the Year.

2002: Pandit Ravi Shankar got his third Grammy for his album Full Circle - Carnegie Hall 2000 in the Best World Music Album category.

Biography

Pandit Ravi Shankar: He is one of those rare names who have made India proud internationally. Known as one of the best exponents of the sitar in the 20th century, Pt. Ravi Shankar has been honoured with four Grammy Awards including one Lifetime Achievement Grammy (posthumous). A 1967 performance at Monterey Film Festival named ‘West Meets East’ brought Shankar a Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance. The album of a charity concert called ‘Concert for Bangladesh’ happened in August 1971. This won the ace musician his second Grammy. His third Grammy came in 2000 for his album ‘Full Circle: Carnegie Hall 2000’. The Lifetime achievement Grammy came only a few days after he passed away due to some heart ailment.

Sukanya

India Today.in , India’s arias “India Today” 5/5/2017

When Pandit Ravi Shankar passed away in December 2010, writers and musicians the world over struggled to convey just how great a contribution he had made. His friend and collaborator, the avant garde composer Philip Glass, put it succinctly: "It may be hard to imagine that one person through the force of his talent, energy and musical personality could have almost single-handedly altered the course of contemporary music in its broadest sense. But that is actually and simply what happened."

Ravi Shankar was a tireless innovator, constantly pushing the boundaries of his art and experimenting with form. Besides Philip Glass, his music enriched and was enriched by other artistes, most famously in the West, the likes of George Harrison, Yehudi Menuhin, and John Coltrane. In his eighties, at a time when most people would be resting on their (in his case, considerable) laurels, Ravi Shankar set sail on a new adventure. He began work on an opera, based on a story from the Mahabharata, of Chyavana, a great sage who meditated so long and so unmovingly that forest ants built their hill around him until he was completely engulfed. Out walking in the forest one day, a beautiful princess, Sukanya, came upon the anthill. Mistaking the sage's eyes for glow-worms buried in the mound, she pierced them with thorns. Blinded, Chyavana emerged from his austerities and demanded Sukanya's hand in marriage. She agreed and they lived together happily.

Perhaps Shankar was drawn to this story, with its theme of love between an older man and a younger woman, because his wife, whose name is also Sukanya, was considerably younger than he. Perhaps he wanted this as his 'swan song'-an operatic offering to his beloved wife. He began work on it in the mid-1990s, but large parts still lay incomplete when he passed away. Sukanya Shankar says that he had told her he was confident that their daughter Anoushka would complete his work if he didn't manage to. "I think he would be very happy to know that his works are in safe hands," she says.

Anoushka Shankar seems to have inherited not only her father's musical DNA but his lively disregard for rigid convention as well. In an echo of Philip Glass's words about her father, fellow musician Nitin Sawhney once wrote that "no one embodies the spirit of innovation and experimentation more evidently than Anoushka". Working with Ravi Shankar's extensive notes and sketches, she and conductor David Murphy finished working on the score-for a full philharmonic orchestra plus classical Indian instruments-but they needed someone to write the words, someone who would see beyond the tokenism of 'fusion music' to the deeper meeting of East and West that Ravi Shankar spent his life exploring. Amit Chaudhuri, whose many novels include Afternoon Raag, and a singer and musician himself (who released an album actually called This is Not Fusion) seemed like the natural choice.

"In fusion music, you tend to throw in a bit of this and a bit of that, and call it 'fusion'," says Chaudhuri. "Ravi Shankar's music contains, rather, a rich sense of one tradition opening itself in a very deep and personal way to another tradition."

How are we to listen to this new musical form? Hearing a raag sung by a soprano is an initially discomforting experience. Not quite one thing, nor the other, it's the musical equivalent of one's taste buds trying to make sense of a completely unexpected flavour. However, 46 years have passed since Shankar's classic comment to the premature applause at the Concert for Bangladesh: "Thank you. If you appreciate the tuning so much, I hope you'll enjoy the playing more." Western audiences these days are used to the sounds of sitar and tabla, whether Philip Glass's opera Satyagraha, sung in Sanskrit, or Nitin Sawhney's Asian-British trip hop. It's not just to do with increasing sophistication; it's just that hybrid forms are the norm, these days.

Chaudhuri's libretto is also something of a hybrid. "I knew I wouldn't be able to tell the story 'straight', as an Indian fairytale or a parable in English verse," he explains. Instead, he took inspiration from a variety of sources-including W.H. Auden and Shakespeare's Two Noble Kinsmen, a play whose authorship is itself disputed.

Sukanya is a story from the Mahabharata, so of course there must be shape-shifting, mistaken identity and magical metamorphoses. Two young princes, appalled that the beauteous Sukanya is wedded to the aged sage, invite him to enter a magical river. He does, and all three of them emerge from the rejuvenating waters, handsome and delicious: a tempting identity parade for Sukanya to pick from. In Chaudhuri's version, the young princes' view is presented-a censorious view of an old man's "inappropriate desire" for the young woman. Yet, to go back to Shakespeare, isn't that just like love? "Love is not love which alters when it alteration finds." Or as Chaudhuri puts it in his moving obituary of Shankar in 2012, "desire and love on the one hand and music on the other were not entirely separate categories of experience for Shankar... Love, like music, entailed its own kind of demands and pain; and music, like love, was evidently a cause for constant rejuvenation."

The Mahabharata is an ancient text, endlessly re-birthed in new forms. Ravi Shankar's opera is just the latest in a long line of such reincarnations. Whether it manages to break the social snobbery associated with classical music and appeal to a wider audience remains to be seen.

-Anita Roy