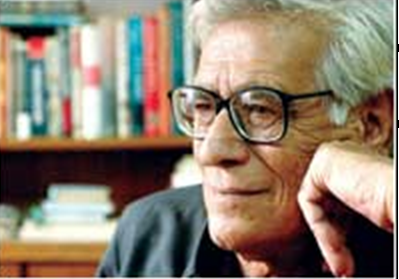

Obaidullah Baig

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Obaidullah Baig

Diary of a film-maker

By Bahzad Alam Khan

Catapulted into fame by the landmark PTV programme Kasauti, Obaidullah Baig is known more for his erudition and prodigious memory than for his film-making accomplishments. And yet no film-maker has made as many documentaries on the history and wildlife of Pakistan as him; there is no river, no pass, no gorge, no mountain, no bird and no reptile of Pakistan that he is unacquainted with. His 135 PTV documentaries, which were poetically titled Sailani Key Sath, enabled him to travel the length and breadth of the country and allowed him to follow in the footsteps of his role model — world-renowned naturalist David Attenborough.

“While we did not have the kind of resources guru David Attenborough did at his disposal, we made up for it by our undiminished commitment to the work,” reminisces Baig, whose 25-minute-long, black-and-white documentary Lakes of Sindh has won him the prestigious Wildscreen Festival award.

“Actually I have always lived in close proximity with nature. You’d be surprised to learn that my family has been reading the National Geographic magazine since 1926 – my father used to subscribe to it long before my birth. My passion for this subject can be gauged from the fact that when they inadvertently shot an elephant dead in the zoo in the late 1960s, I wrote an editorial in Hurriyet, where I worked at the time under veteran journalist Farhad Zaidi.”

His passion for film-making can also be gauged from the fact that he left for Peshawar to make a short documentary on Buddha on the day after his wedding. Little wonder that he has made over 300 documentaries during the course of his eventful career.

Baig points out that making a documentary is essentially a labour of love which is hardly ever appreciated and almost never rewarded.

“Having said that, let me also make it clear that making a documentary is great fun. It particularly suits my temperament because it requires a great deal of research and reading. Besides, it requires extensive travelling and enables me to quench my wanderlust,” he adds.

Baig’s last venture took him to a Central Asian state.“I made Pakistans first documentary on Turkmenistan. I went to the Central Asian republic twice – first in August 2001 to do the spadework and again in September for 37 days to do the filming. I returned with 26 hours of footage. Once completed, the running time of the documentary is 24 minutes. You can well imagine how much work must have gone into its production.”

Baig’s recent offering is a seven-part documentary that takes a girl belonging to a well-known family from Scotland to various parts of Pakistan. ‘One of the objectives of the documentary is to dispel misgivings the world has about Pakistan. Unfortunately, it is portrayed, especially in the Western media, as a country where bombs are going off all the time and people are getting killed. We took the Scottish girl all across the country and not a single unsavoury incident occurred,’ he says

Baig’s recent offering is a seven-part documentary that takes a girl belonging to a well-known family from Scotland to various parts of Pakistan and enables her to mingle with other tourists and local people and partake of local hospitality. The documentaries are appropriately subtitled Not a Stranger in Pakistan.

“One of the objectives of the documentary is to dispel misgivings the world has about Pakistan. Unfortunately, it is portrayed, especially in the Western media, as a country where bombs are going off all the time and people are getting killed. We took the teenage Scottish girl all across the country and not a single unsavoury incident occurred,” he says.

“I also wanted to make a comprehensive series of documentaries on Pakistan covering all important places of interest – archaeological ruins, museums, tombs, historical buildings, wildlife sanctuaries, national parks, well-known places of worship, etc. My latest documentaries, Pakistan 2100, are the materialisation of my long-cherished dream.”

Baig explains that each of the seven documentaries touch on a separate theme. Cradles of Civilisation is about the archaeological ruins in Mohenjodaro, Harappa and Mehrgarh. The Messengers of Love And Peace sheds light on the contribution of Sufi poets. The Heritage of Splendour gives an overview of historical buildings in Pakistan.

A Day At The Khyber Pass takes viewers to one of the most iconic places in Pakistani history. Border Rituals puts the spotlight on the goose-stepping ceremonies that take place daily at the borders between Pakistan and India. Salty Wonderland is about the salt mines of the country. And lastly, Forests And Wildlife focuses on the subject that has always been close to Baig’s heart.

Baig says that the 65 hours of footage that he has shot for these documentaries could enable him to make a couple more episodes. And since Baig is an old PTV loyalist – his resignation from the state-run TV channel notwithstanding – his documentaries will be first made available to PTV.

Baig feels that the potential of Pakistan, which is essentially an agricultural country, has not been adequately explored by wildlife documentary-makers. “For instance, there’s no reason why Pakistan should remain unrepresented in the Wildscreen Festival, which is the world’s largest and most prestigious event for the wildlife and environmental film-making industry.”

According to him, uncontrolled hunting has made wildlife film-making – a daunting undertaking in the best of times – a most difficult exercise. “The moment you train your camera on a bird in a forest, it flies away, thinking that it’s being shot at. The least that the government can do is put an effective ban on hunting so that Pakistans wildlife is preserved,” he suggests.