North Indian Popular Religion:10 -Praying for relief from diseases

This article is an extract from THE POPULAR RELIGION AND FOLK-LORE OF NORTHERN INDIA WESTMINSTER Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor |

North Indian Popular Religion:10 -Praying for relief from diseases

THE GODLINGS OF DISEASE

Καὶ γὰρ τοῖσι κακὸν χρυσόθρονος Ἄρτεμις ὦρσεν

Χωσαμένη ὃ οἰ οὔτι θαλύσια γουνῶ ἀλωῆς

Οἰνεὺς ῥέξ.

Iliad ix. 533–535.

We now come to consider a class of rural godlings, the deities who control disease.

The Demoniacal Theory of Disease.

It is a commonplace of folk-lore and the beliefs of all savage races that disease and death are not the result of natural causes, but are the work of devils and demons, witchcraft, the Evil Eye, and so forth. It is not difficult to understand the basis on which beliefs of this class depend. There are certain varieties of disease, such as hysteria, dementia, epilepsy, convulsions, the delirium of fever, which in the rural mind indicate the actual working of an evil spirit which has attacked the patient.

There are, again, others, such as cholera, which are so sudden and unexpected, so irregular in their appearances, so capricious in the victims which they select, that they naturally suggest the idea that they are caused by demons. Even to this day the belief in the origin of disease from spirit possession is still common in rural England. Fits, the falling sickness, ague, cramp, warts, are all believed to be caused by a spirit entering the body of the patient. Hence comes the idea that the spirit which is working the mischief can be scared by a charm or by the exorcism of a sorcerer.

They say to the ague, “Ague! farewell till we meet in hell,” and to the [124]cramp, “Cramp! be thou faultless, as Our Lady was when she bore Jesus.”

It is needless to say that the same theory flourishes in rural India. Thus, in Râjputâna,1 sickness is popularly attributed to Khor, or the agency of the offended spirits of deceased relations, and for treatment they call in a “cunning man,” who propitiates the Khor by offering sweetmeats, milk, and similar things, and gives burnt ash and black pepper sanctified by charms to the patient.

The Mahadeo Kolis of Ahmadnagar believe that every malady or disease that seizes man, woman, child, or cattle is caused either by an evil spirit or by an angry god. The Bijapur Vaddars have a yearly feast to their ancestors to prevent the dead bringing sickness into the house.2

Further east in North Bhutan all diseases are supposed to be due to possession, and the only treatment is by the use of exorcisms. Among the Gâros, when a man sickens the priest asks which god has done it. The Kukis and Khândhs believe that all sickness is caused by a god or by an offended ancestor.3

So among the jungle tribes of Mirzapur, the Korwas believe that all disease is caused by the displeasure of the Deohâr, or the collective village godlings. These deities sometimes become displeased for no apparent reason, sometimes because their accustomed worship is neglected, and sometimes through the malignity of some witch. The special diseases which are attributed to the displeasure of these godlings are fever, diarrhœa and cough. If small-pox comes of its own accord in the ordinary form, it is harmless, but a more dangerous variety is attributed to the anger of the local deities. Cholera and fever are regarded as generally the work of some special Bhût or angry ghost. The Kharwârs believe that disease is due to the Baiga not having paid proper attention to Râja Chandol and the other tutelary godlings of the village. The Pankas think that [125]disease comes in various ways—sometimes through ghosts or witches, sometimes because the godlings and deceased ancestors were not suitably propitiated.

All these people believe that in the blazing days of the Indian summer the goddess Devî flies through the air and strikes any child which wears a red garment. The result is the symptoms which less imaginative people call sunstroke. Instances of similar beliefs drawn from the superstitions of the lower races all over the country might be almost indefinitely extended. Even in our own prayers for the sick we pray the Father “to renew whatsoever has been decayed by the fraud and malice of the Devil, or by the carnal will and frailness” of the patient.

Leprosy is a disease which is specially regarded as a punishment for sin, and a Hindu affected by this disease remains an outcast until he can afford to undertake a purificatory ceremony. Even lesser ailments are often attributed to the wrath of some offended god or saint. Thus, in Satâra, the King Sateswar asked the saint Sumitra for water. The sage was wrapped in contemplation, and did not answer him. So the angry monarch took some lice from the ground and threw them at the saint, who cursed the King with vermin all over his body. He endured the affliction for twelve years, until he was cured by ablution at the sacred fountain of Devrâshta.4 As we shall see, the Bengâlis have a special deity who rules the itch.

From ideas of this kind the next stage is the actual impersonation of the deity who brings disease, and hence the troop of disease godlings which are worshipped all over India, and to whose propitiation much of the thoughts of the peasant are devoted.

Small pox

Sîtalâ, the Goddess of Small-pox.

Of these deities the most familiar is Sîtalâ, “she that loves the cool,” so called euphemistically in consequence of the fever which accompanies small-pox, the chief infant [126]plague of India, which is under her control. Sîtalâ has other euphemistic names. She is called Mâtâ, “the Mother” par excellence; Jag Rânî, “the queen of the world;” Phapholewâlî, “she of the vesicle;” Kalejewâlî, “she who attacks the liver,” which is to the rustic the seat of all disease. Some call her Mahâ Mâî, “the great Mother.”

These euphemistic titles for the deities of terror are common to all the mythologies. The Greeks of old called the awful Erinyes, the Eumenides, “the well-meaning.” So the modern Greeks picture the small-pox as a woman, the enemy of children, and call her Sunchoremene, “indulgent,” or “exorable,” and Eulogia, “one to be praised or blessed;” and the Celts call the fairies “the men of peace” and “the good people,” or “good neighbours.”5

In her original form as a village goddess she has seldom a special priest or a regular temple. A few fetish stones, tended by some low-class menial, constitute her shrine. As she comes to be promoted into some form of Kâlî or Devî, she is provided with an orthodox shrine. She receives little or no respect from men, but women and children attend her service in large numbers on “Sîtalâ’s seventh,” Sîtalâ Kî Saptamî, which is her feast day. In Bengal she is worshipped on a piece of ground marked out and smeared with cow-dung. A fire being lighted, and butter and spirits thrown upon it, the worshipper makes obeisance, bowing his forehead to the ground and muttering incantations.

A hog is then sacrificed, and the bones and offal being burnt, the flesh is roasted and eaten, but no one must take home with him any scrap of the victim.6

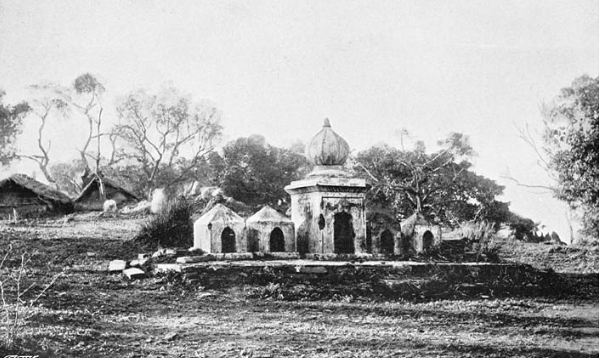

SHRINE OF SÎTALÂ AND DISEASE GODLINGS.

Two special shrines of Sîtalâ in Upper India may be specially referred to. That at Kankhal near Hardwâr has a curious legend, which admirably illustrates the catholicity of Hinduism. Here the local Sîtalâ has the special title of Turkin, or “the Muhammadan lady.” There was once a [127]princess born to one of the Mughal Emperors, who, according to the traditions of the dynasty, when many of the chief ladies of the harem were of Hindu birth, had a warm sympathy for her ancestral faith.

So she made a pilgrimage to Hardwâr, and thence set off to visit the holy shrines situated in the upper course of the Ganges. When she reached the holy land of Badarinâth, the god himself appeared to her in a dream, and warned her that she being a Musalmân, her intrusion into his domains would probably encourage the attacks of the infidel. So he ordered her to return and take up her abode in Kankhal, where as a reward for her piety she should after her death become the guardian goddess of children and be deified as a manifestation of Sîtalâ. So after her death a temple was erected on the site of her tomb, and she receives the homage of multitudes of pilgrims. There is another noted shrine of Sîtalâ at Râêwala, in the Dehra Dûn District. She is a Satî, Gândharî, the wife of Dhritarâshtra, the mother of Duryodhana.

When Dhritarâshtra, through the force of his divine absorption, was consumed with fire at Sapta-srota, near Hardwâr, Gândharî also jumped into the fire and became Satî with her husband. Then, in recognition of her piety, the gods blessed her with the boon that in the Iron Age she should become the guardian deity of children and the goddess of small-pox in particular. Another noted Sîtalâ in this part of the country is the deity known as Ujalî Mâtâ, or “the White Mother,” who has a shrine in the Muzaffarnagar District.

Here vast crowds assemble, and women make vows at her temple for the boon of sons, and when a child is born they take it there and perform their vow by making the necessary offering to the goddess. One peculiarity of the worship of the Kankhal goddess and of Ujalî Mâtâ is that calves are released at her shrine. This can hardly be anything else but a survival of the rite of cattle slaughter, and this is one of many indications that the worship of Sîtalâ is a most primitive cult, and probably of indigenous origin.

Sîtalâ, according to one story, is only the eldest of a band [128]of seven sisters, by whom the pustular group of diseases is supposed to be caused. So the charmer Lilith has twelve daughters, who are the twelve kinds of fevers, and this arrangement of diseases or evil spirits in categories of sevens or twelves is found in the Chaldaic magic.7 Similarly in the older Indian mythology we have the seven Mâtrîs, the seven oceans, the seven Rishis, the seven Adityas and Dânavas, and the seven horses of the sun, and numerous other combinations of this mystic number.

One list gives their names as Sîtalâ, Masânî, Basanti, Mahâ Mâî, Polamdê, Lamkariyâ, and Agwânî.8 We shall meet Masânî or Masân, the deity of the cremation ground, in another connection. Basantî is the “yellow goddess,” so called probably on account of the colour of the skin in these diseases. Mahâ Mâî is merely “the great Mother.” Polamdê is possibly “she who makes the body soft or flabby,” and Lamkariyâ, “she that hasteneth.” Agwânî is said to mean “the leader,” and by one account, Agwân, who has twenty-five thousand votaries, according to the last census returns, in the North-West Provinces, is the son of Râja Ben, or Vena, and the brother of the small-pox sisters.

At Hardwâr they give the names of the seven sisters as Sîtalâ, Sedalâ, Runukî, Jhunukî, Mihilâ, Merhalâ, and Mandilâ, a set of names which smacks of some modification of an aboriginal cultus.

Their shrines cluster round the special shrine of Sîtalâ, and the villagers to the west of the North-West Provinces call them her Khidmatgârs, or body servants. Round many of the shrines again, as at Kankhal, we find a group of minor shrines, which by one explanation are called the shrines of the other disease godlings.

Villagers say that when disease appears in a family, the housewife comes and makes a vow, and if the patient recovers she makes a little shrine to the peculiar form of Devî which she considers responsible for the illness. The Brâhmans say that these minor shrines are in honour of the Yoginîs, who are usually [129]said to number eight—Mârjanî, Karpûratilakâ, Malayagandhinî Kauamudikâ, Bherundâ, Mâtâlî, Nâyakî, Jayâ or Subhâchârâ, Sulakshanâ and Sunandâ. In the Gurgâon District, accompanying images of Sîtalâ, is one of Sedhu Lâla, who is inferior to her, yet often worshipped before her, because he is regarded as her servant and intercessor.

Copper coins are thrown behind her shrine into a saucer, which is known as her Mâlkhâna or Treasury. Rice and other articles of food are placed in front of her shrine, and afterwards distributed to Chamârs, the currier caste, and to dogs.9

Like so many deities of this class Sîtalâ is on the way to promotion to the higher heaven. In some places she is identified with Kâlikâ Bhavânî, and one list of the seven small-pox sisters gives their names as Sîtalâ, Phûlmatî, Chamariyâ, Durgâ Kâlî, Mahâ Kâlî, and Bhadrâ Kâlî. This has obviously passed through the mill of Brâhmanism. Of these, Chamariyâ is doubtless allied to Châmar, who is a vaguely described low-caste deity, worshipped in the North-Western Provinces. Some say he is the ghost of a Chamâr, or worker in leather, who died an untimely death.

Chamariyâ is said to be the eldest and Phûlmatî the youngest sister of Sîtalâ. She, by the common account, takes her name from the pustules (phûl) of the disease. She brings the malady in its mildest form, and the worst variety is the work of Sîtalâ in person. She lives in the Nîm tree, and hence a patient suffering from the disease is fanned with its leaves. A very bad form of confluent small-pox is the work of Chamariyâ, who must be propitiated with the offering of a pig through a Chamâr or other low-caste priest.

The influence of Kâlî in her threefold form is chiefly felt in connection with other pustular diseases besides small-pox. Earthenware images of elephants are placed at her shrine, and her offerings consist of cakes, sweetmeats, pigs, goats, sheep, and black fowls. Bhadrâ Kâlî is the least formidable of all. The only person who has influence over Kâlî is the Ojha, or sorcerer, who, when [130]cholera and similar epidemics prevail, collects a subscription and performs a regular expiatory service.

Connection of Sîtalâ with Human Sacrifice

In her form as household goddess, Sîtalâ is often known as Thandî, or “the cool one,” and her habitation is in the house behind the water-pots, in the cold, damp place where the water drips. Here she is worshipped by the house-mother, but only cold food or cold water is offered to her.

There is, however, a darker side to the worship of Sîtalâ and the other disease godlings than this mild household service. In 1817 a terrible epidemic of cholera broke out at Jessore. “The disease commenced its ravages in August, and it was at once discovered that the August of this year had five Saturdays (a day under the influence of the ill-omened Sani).

The number five being the express property of the destructive Siva, a mystical connection was at once detected, the infallibly baneful influence of which it would have been sacrilege to question. On the night of the 27th a strange commotion spread through the villages adjacent to the station. A number of magicians were reported to have quitted Marelli with a human head in their possession, which they were to be directed by the presence of supernatural signs to leave in a certain, and to them unknown, village.

The people on all sides were ready by force to arrest the progress of these nocturnal visitors. For the prophecy foretold that wherever the head fell, the destroying angel terminating her sanguinary course would rest, and the demon of death, thus satisfied, would refrain from further devastation in that part of the country. Dr. Tytler says that on that night, while walking along the road, endeavouring to allay the agitation, the judge and he perceived a faint light arising from a thick clump of bamboos. Attracted to the spot, they found a hut which was illuminated, and contained images of five Hindu gods, one of which was Sîtalâ, the celebrated and formidable Aulâ Bîbî, [131]‘Our Lady of the Flux,’ an incarnation of Kâlî, who it is believed is one day to appear riding on a horse for the purpose of slaughtering mankind, and of setting the world on fire.

In front of the idol a female child about nine years of age lay on the ground. She was evidently stupefied with intoxicating drugs, and in this way prepared to answer responses to such questions as those initiated into the mysteries should think proper to propose.”10 There is much in this statement which is open to question, and it seems doubtful whether, as Dr. Chevers is disposed to believe, the case was really one of intended human sacrifice.

Small-pox Worship in Bengal

In Bengal the divine force antagonistic to Sîtalâ is Shashthî, “goddess of the sixth,” who is regarded as the special guardian of children. The worship of Shashthî rests on a physiological fact, which has only recently been applied to explain this special form of worship. The most fatal disease of Indian children is a form of infantile lock-jaw, which is caused by the use of a coarse, blunt instrument, such as a sickle, for severing the umbilical cord.

This disease usually makes its appearance between the sixth and twelfth day of the life of the child, and hence we have the formal rites of purification from the birth pollution performed as the Chhathî on the sixth and the Barahî on the twelfth day after delivery.

“In Bengal when small-pox rages, the gardeners are busiest. As soon as the nature of the disease is determined, the physician retires and a gardener is summoned. His first act is to forbid the introduction of meat, fish, and all food requiring oil or spices for its preparation. He then ties a lock of hair, a cowry shell, a piece of turmeric, and an article of gold on the right wrist of the patient. (The use of these articles as scarers of evil spirits will be considered later on.) The sick person is then laid on the Majhpatta, the young and unexpanded leaf of the plantain tree, and [132]milk is prescribed as the sole article of food.

He is fanned with a branch of the sacred Nîm (Azidirachta Indica), and any one entering the chamber is sprinkled with water. Should the fever become aggravated and delirium ensue, or if the child cries much and sleeps little, the gardener performs the Mâtâ Pûjâ. This consists in bathing an image of the goddess causing the disease, and giving a draught of the water to drink. To relieve the irritation of the skin, pease meal, turmeric, flour or shell sawdust is sprinkled over the body.

If the eruption be copious, a piece of new cloth in the figure of eight is wrapped round the chest and shoulders. On the night between the seventh and eighth days of the eruption, the gardener has much to do. He places a water-pot in the sick-room, and puts on it rice, a cocoanut, sugar, plantains, a yellow rag, flowers, and a few Nîm leaves. Having mumbled several spells (mantra), he recites the tale (qissa) of the particular goddess, which often occupies several hours. When the pustules are mature, the gardener dips a thorn of the Karaunda (Carissa) in sesamum oil and punctures each one.

The body is then anointed with oil, and cooling fruits are given. When the scabs have peeled off, another ceremony called Godâm is gone through. All the offerings on the water-pot are rolled in a cloth and fastened round the waist of the patient. The offerings are the perquisite of the gardener, who also receives a fee. Government vaccinators earn a considerable sum yearly by executing the Sîtalâ worship, and when a child is vaccinated, a portion of the service is performed”—a curious compromise between the indigenous faith and European medical science.11

The special Tirhût observance of the Jur Sîtal or “smallpox fever” feast will be more conveniently considered in connection with other usages of the same kind.

Mâtangî Saktî and Masân

We have already seen that Sîtalâ is in the stage of promotion to the Brâhmanical heaven. Here her special name [133]is Mâtangî Saktî, a word which has been connected with Mâtâ and Masân, but really refers to Durgâ-Devî in her terrible elephant form. Masân or Masânî is quite a different goddess. She resides at the Masân or cremation ground, and is greatly dreaded.

The same name is in the eastern district of the North-Western Provinces applied to the tomb of some low-caste man, very often a Teli or oilman, or a Dhobi or washerman, both of whose ghosts are generally obnoxious. Envious women will take the ashes from a cremation ground and throw them over an enemy’s child.

This is said to cause them to be “under the influence of the shadow” (Sâya, Chhâya) and to waste away by slow decline. This idea is familiar in folk-lore. All savages believe that their shadow is a part of themselves, that if it be hurt the owner of it will feel pain, that a man may lose his shadow altogether and thus be deprived of part of his soul and strength, and that vicious people, as in the present case, can fling their shadow upon you and cause you injury.12

Mâtangî Saktî, again, appears in at least eight forms—Raukâ Devî, Ghraukâ Devî, Melâ Devî, Mandlâ Devî, Sîtalâ Devî, Durgâ Devî and Sankarâ Devî, a collection of names which indicates the extraordinary mixture of beliefs, some of them importations from the regular mythology, but others obscure and local manifestations of the deity, out of which this worship has been developed.

She is described as having ears as large as a winnowing fan, projecting teeth, a hideous face with a wide open mouth. Her vehicle is the ass, an animal very often found in association with shrines of Sîtalâ.

She carries a broom and winnowing fan with which she sifts mankind, and in one hand a pitcher and ewer. This fan and broom are, as we shall see later on, most powerful fetishes. All this is sheer mythology at its lowest stage, and represents the grouping of various local fetish beliefs on the original household worship. [134]

Journey forbidden during an Epidemic of Small-pox

During a small-pox epidemic no journey, not even a pilgrimage to a holy shrine, should be undertaken. Gen. Sleeman13 gives a curious case in illustration of this: “At this time the only son of Râma Krishna’s brother, Khushhâl Chand, an interesting boy of about four years of age, was extremely ill of small-pox.

His father was told that he had better defer his journey to Benares till the child should recover; but he could neither eat nor sleep, so great was his terror lest some dreadful calamity should befall the whole family before he could expiate a sacrilege which he had committed unwittingly, or take the advice of his high priest, as to the best manner of doing so, and he resolved to leave the decision to God himself.

He took two pieces of paper and having caused Benares to be written on one and Jabalpur on the other, he put them both in a brass vessel. After shaking the vessel well, he drew forth that on which Benares had been written. ‘It is the will of God,’ said Râma Krishna. All the family who were interested in the preservation of the poor boy implored him not to set out, lest the Devî who presides over small-pox should be angry.

It was all in vain. He would set out with his household god, and unable to carry it himself, he put it upon a small litter upon a pole, and hired a bearer to carry it at one end while he supported the other. His brother Khushhâl Chand sent his second wife at the same time with offerings to the Devî, to ward off the effects of his brother’s rashness from the child. By the time his brother had got with his god to Adhartâl, three miles from Jabalpur, he heard of the death of his nephew.

But he seemed not to feel this slight blow in the terror of the dreadful, but undefined, calamity which he felt to be impending over him and the whole family, and he went on his road. Soon after, an infant son of his uncle died of the same disease, and the whole town at once became divided into two parties—those who held that the child had been killed by the Devî as a punishment for Râma Krishna’s [135]presuming to leave Jabalpur before they recovered, and those who held that they were killed by the god Vishnu himself for having deprived him of one of his arms.

Khushhâl Chand’s wife sickened on the road and died before reaching Mirzapur; and as the Devî was supposed to have nothing to say to fevers, this event greatly augmented the advocates of Vishnu.”

Observances during Small-pox Epidemics

In the Panjâb when a child falls ill of small-pox no one is allowed to enter the house, especially if he have bathed, washed, or combed his hair, and if any one does come in, he is made to burn incense at the door. Should a thunderstorm come on before the vesicles have fully come out, the sound is not allowed to enter the ear of the sick child, and metal plates are violently beaten to drown the noise of the thunder. For six or seven days, when the disease is at its height, the child is fed with raisins covered with silver leaf.

When the vesicles have fully developed it is believed that Devî Mâtâ has come. When the disease has abated a little, water is thrown over the child. Singers and drummers are summoned and the parents make with their friends a procession to the temple of Devî, carrying the child dressed in saffron-coloured clothes.

A man goes in advance with a bunch of sacred grass in his hands, from which he sprinkles a mixture of milk and water. In this way they visit some fig-tree or other shrine of Devî, to which they tie red ribbons and besmear it with red lead, paint and curds.14

One method of protecting children from the disease is to give them opprobrious names, and dress them in rags. This, with other devices for disease transference, will be discussed later on. We have seen that the Nîm tree is supposed to influence the disease; hence branches of it are hung over the door of the sick-room.

Thunder disturbs the goddess in possession of the child, so the family flour-mill, which, as as we shall see, has mystic powers, is rattled near the child. [136]Another device is to feed a donkey, which is the animal on which Sîtalâ rides. This is specially known in the Panjâb as the Jandî Pûjâ.15 In the same belief that the patient is under the direct influence of the goddess, if death ensues the purification of the corpse by cremation is considered both unnecessary and improper. Like Gusâîns, Jogis, and similar persons who are regarded as inspired, those who die of this disease are buried, not cremated.

As Sir A. C. Lyall observes,16 “The rule is ordinarily expounded by the priests to be imperative, because the outward signs and symptoms mark the actual presence of divinity; the small-pox is not the god’s work, but the god himself manifest; but there is also some ground for concluding that the process of burying has been found more wholesome than the hurried and ill-managed cremation, which prevails during a fatal epidemic.” Gen. Sleeman gives an instance of an outbreak of the disease which was attributed to a violation of this traditional rule.17

Other diseases

Minor Disease Godlings

There are a number of minor disease godlings, some of whom may be mentioned here. The Benares godling of malaria is Jvaraharîsvara, “the god who repels the fever.” The special offering to him is what is called Dudhbhanga, a confection made of milk, the leaves of the hemp plant and sweetmeats. Among the Kols of Chaibâsa, Bangara is the godling of fever and is associated with Gohem, Chondu, Negra and Dichali, who are considered respectively the godlings of cholera, the itch, indigestion and death.

The Bengâlis have a special service for the worship of Ghentu, the itch godling. The scene of the service is a dunghill. A broken earthenware pot, its bottom blackened with constant use for cooking, daubed white with lime, interspersed with a few streaks of turmeric, together with a branch or two of the Ghentu plant, and last, not least, a broomstick of the genuine palmyra or cocoanut stock, serve [137]as the representation of the presiding deity of itch.

The mistress of the family, for whose benefit the worship is done, acts as priestess. After a few doggrel lines are recited, the pot is broken and the pieces collected by the children, who sing songs about the itch godling.18

Some of these godlings are, like Shashthî, protectors of children from infantile disorders. Such are in Hoshangâbâd Bijaysen, in whose name a string, which, as we shall see, exercises a powerful influence over demons, is hung round the necks of children from birth till marriage, and Kurdeo, whose name represents the Kuladevatâ, or family deity. Among the Kurkus he presides over the growth and health of the children in three or four villages together.19 Acheri, a disease sprite in the Hills, particularly favours those who wear red garments, and in his name a scarlet thread is tied round the throat as an amulet against cold, and goitre.

Ghanta Karana, “he who has ears as broad as a bell,” or “who wears bells in his ears,” is another disease godling of the Hills. He is supposed to be of great personal attractions, and is worshipped under the form of a water jar as the healer of cutaneous diseases. He is a gate-keeper, or, in other words, a godling on his promotion, in many of the Garhwâl temples.20

Among the Kurkus of Hoshangâbâd, Mutua Deo is represented by a heap of stones inside the village. His special sacrifice is a pig, and his particular mission is to send epidemics, and particularly fevers, in which case he must be propitiated with extraordinary sacrifices.21

One of the great disease Mothers is Marî Bhavânî. She has her speciality in the regulation of cholera, which she spreads or withholds according to the attention she receives. They tell a curious story about her in Oudh. Safdar Jang, having established his virtual independence of the Mughal Empire, determined to build a capital.

He selected as the [138]site for it the high bank of the Gûmti, overlooking Pâparghât in Sultânpur. And but for the accident of a sickly season, that now comparatively unknown locality might have enjoyed the celebrity which afterwards fell to the lot of Faizâbâd. The fort was already begun when the news reached the Emperor, who sent his minister a khilat, to all outward appearance suited to his rank and dignity. The royal gift had been packed up with becoming care, and its arrival does not seem to have struck Safdar Jang as incompatible with the rebellious attitude which he had assumed.

The box in which it was enclosed was opened with due ceremony, when it was discovered that the Emperor, with grim pleasantry, had selected as an appropriate gift an image of Marî Bhavânî. The mortality which ensued in Safdar Jang’s army was appalling, and the site was abandoned, Marî Bhavânî being left in sole possession. Periodical fairs are now held there in her honour.22

Cholera

Hardaul Lâla, the Cholera Godling

But the great cholera godling of Northern India is Hardaul, Hardaur, Harda, Hardiya or Hardiha Lâla. It is only north of the Jumnâ that he appears to control the plague, and in Bundelkhand, his native home, he seems to have little connection with it. With him we reach a class of godlings quite distinct from nearly all those whom we have been considering. He is one of that numerous class who were in their lifetime actual historical personages, and who from some special cause, in his case from the tragic circumstances of his death, have been elevated to a seat among the hosts of heaven.

Hardaur Lâla, or Dîvân Hardaur, was the second son of Bîr Sinha Deva, the miscreant Râja of Orchha, in Bundelkhand, who, at the instigation of Prince Jahângîr, assassinated the accomplished Abul Fazl, the litterateur of the court of Akbar.23 His brother Jhajhâr, or Jhujhâr, Sinh succeeded to the throne [139]on the death of his father; and after some time suspecting Hardaur of undue intimacy with his wife, he compelled her to poison her lover with all his companions at a feast in 1627 A.D.

After this tragedy it happened that the daughter of the Princess Kanjâvatî, sister of Jhajhâr and Hardaur, was about to be married. Her mother, according to the ordinary rule of family etiquette, sent an invitation to Jhajhâr Sinh to attend the wedding. He refused with the mocking taunt that she would be wise to invite her favourite brother Hardaur. Thereupon, she in despair went to his cenotaph and lamented his wretched end. Hardaur from below answered her cries, and promised to attend the wedding and make all the necessary arrangements.

The ghost kept his promise, and arranged the marriage ceremony as befitted the honour of his house.

Subsequently he is said to have visited the bedside of the Emperor Akbar at midnight, and besought him to issue an order that platforms should be erected in his name, and honour be paid to him in every village of the Empire, promising that if he were duly propitiated, no wedding should ever be marred with storm or rain, and that no one who before eating presented a share of his meal to him, should ever want for bread. Akbar, it is said, complied with these requests, and since then the ghost of Hardaul has been worshipped in nearly every village in Northern India. But here, as in many of these legends, the chronology is hopeless. Akbar died in 1605 A.D., and the murder of Hardaul is fixed in 1627.

He is chiefly honoured at weddings, and in the month of Baisâkh (May), when the women, particularly those of the lower classes, visit his shrine and eat the offerings presented to him. The shrine is always erected outside the hamlet, and is decorated with flags. On the day but one before the arrival of a wedding procession, the women of the family worship Hardaul, and invite him to the ceremony. If any signs of a storm appear, he is propitiated with songs, one of the best known of which runs thus— [140]

Lâla! Thy shrine is in every hamlet!

Thy name throughout the land!

Lord of the Bundela land!

May God increase thy fame!

Or in the local patois—

Gânwân chauntra,

Lâla desan nâm:

Bundelê des kê Raiya,

Râû kê.

Tumhârî jay rakhê

Bhagwân!

Many of these shrines have a stone figure of the hero represented on horseback, set up at the head or west side of the platform. From his birthplace Hardaul is also known as Bundela, and one of the quarters in Mirzapur, and in the town of Brindaban in the Mathura District, is named after him.24

But while in his native land of Bundelkhand Hardaul is a wedding godling, in about the same rank as Dulha Deo among the Drâvidian tribes, to the north of the Jumnâ it is on his power of influencing epidemics of cholera that his reputation mainly rests.

The terrible outbreak of this pestilence, which occurred in the camp of the Governor-General, the Marquess Hastings, during the Pindâri war, was generally attributed by the people to the killing of beef for the use of the British troops in the grove where the ashes of Hardaul repose. Sir C. A. Elliott remarks that he has seen statements in the old official correspondence of 1828 A.D., when we first took possession of Hoshangâbâd, that the district officers were directed to force the village headmen to set up altars to Hardaul Lâla in every village.

This was part of the system of “preserving the cultivators,” since it was found that they ran away, if their fears of epidemics were not calmed by the respect paid to the local gods. But in Hoshangâbâd, the worship of Hardaul Lâla has fallen into great neglect in recent times, the repeated [141]recurrence of cholera having shaken the belief in the potency of his influence over the disease.25

Exorcism of the Cholera Demon

Mention has been already made of the common belief in an actual embodiment of pestilence in a human or ghostly form. A disease so sudden and mysterious as cholera is naturally capable of a superstitious explanation of this kind. Everywhere it is believed to be due to the agency of a demon, which can be expelled by noise and special incantations, or removed by means of a scapegoat.

Thus, the Muhammadans of Herat believed that a spirit of cholera stalked through the land in advance of the actual disease.26 All over Upper India, when cholera prevails, you may see fires lighted on the boundaries of villages to bar the approach of the demon of the plague, and the people shouting and beating drums to hasten his departure. On one occasion I was present at such a ceremonial while out for an evening drive, and as we approached the place the grooms advised us to stop the horses in order to allow the demon to cross the road ahead of us without interruption.

This expulsion of the disease spirit is often a cause of quarrels and riots, as villages who are still safe from the epidemic strongly resent the introduction of the demon within their boundaries. In a recent case at Allahâbâd a man stated that the cholera monster used to attempt to enter his house nightly, that his head resembled a large earthen pot, and that he and his brother were obliged to bar his entrance with their clubs.

Another attributed the immunity of his family to the fact that he possessed a gun, which he regularly fired at night to scare the demon. Not long ago some men in the same district enticed the cholera demon into an earthen pot by magical rites, and clapping on the lid, formed a procession in the dead of night for the purpose of carrying the pot to a neighbouring village, with [142]which their relations were the reverse of cordial, and burying it there secretly. But the enemy were on the watch, and turned out in force to frustrate this fell intent. A serious riot occurred, in the course of which the receptacle containing the evil spirit was unfortunately broken and he escaped to continue his ravages in the neighbourhood.27 In Bombay, when cholera breaks out in a village, the village potter is asked to make an image of the goddess of cholera.

When the image is ready, the village people go in procession to the potter’s house, and tell him to carry the image to a spot outside the village. When it is taken to the selected place, it is first worshipped by the potter and then by the villagers.28 Here, as in many instances of similar rites, the priest is a man of low caste, which points to the indigenous character of the worship.

In the western districts of the North-Western Provinces the rite takes a more advanced form. When cholera prevails, Kâlî Devî is worshipped, and a magic circle of milk and spirits is drawn round the village, over which the cholera demon does not care to step. They have also a reading of the Scriptures in honour of Durgâ, and worship a Satî shrine, if there be one in the village.

The next stage is the actual scapegoat, which is, as we shall see, very generally used for this purpose. A buffalo bull is marked with a red pigment and driven to the next village, where he carries the plague with him. Quite recently, at Meerut, the people purchased a buffalo, painted it red and led the animal through the city in procession. Colonel Tod describes how Zâlim Sinh, the celebrated regent of Kota, drove cholera out of the place. “Having assembled the Brâhmans, astrologers and those versed in incantations, a grand rite was got up, sacrifices made, and a solemn decree of banishment was pronounced against Marî, the cholera goddess. Accordingly an equipage was prepared for her, decorated with funeral emblems, painted black and drawn by a double team of black oxen; bags of grain, also black, [143]were put into the vehicle, that the lady might not go without food, and driven by a man in sable vestments, followed by the yells of the populace, Marî was deported across the Chambal river, with the commands of the priests that she should never again set foot in Kota. No sooner did my deceased friend hear of her expulsion from that capital, and being placed on the road for Bûndi, than the wise men of the city were called on to provide means to keep her from entering therein.

Accordingly, all the water of the Ganges at hand was in requisition; an earthen vessel was placed over the southern portal from which the sacred water was continually dripping, and against which no evil could prevail. Whether my friend’s supply of the holy water failed, or Marî disregarded such opposition, she reached the palace.”29

Cholera caused by Witchcraft

In Gujarât, among the wilder tribes, the belief prevails that cholera is caused by old women who feed on the corpses of the victims of the pestilence. Formerly, when a case occurred their practice was to go to the soothsayer (Bhagat), find out from him who was the guilty witch, and kill her with much torture. Of late years this practice has, to a great extent, ceased. The people now attribute an outbreak to the wrath of the goddess Kâlî, and, to please her, draw her cart through the streets, and lifting it over the village boundaries, offer up goats and buffaloes. Sometimes, to keep off the disease, they make a magic circle with milk or coloured threads round the village.

At Nâsik, when cholera breaks out in the city, the leading Brâhmans collect in little doles from each house a small allowance of rice, put the rice in a cart, take it beyond the limits of the town, and there it is thrown away.30

A visitation of the plague in Nepâl was attributed to the Râja insisting on celebrating the Dasahra during an intercalary month. On another occasion the arrival of the disease was attributed to the Evil Eye of Saturn and other [144]planets, which secretly came together in one sign of the zodiac. A third attack was supposed to be caused by the Râja being in his eighteenth year, and the year of the cycle being eighty-eight—eight being a very unlucky number.31

So the Gonds try to ward off the anger of the spirits of cholera and small-pox by sacrifices, and by thoroughly cleaning their villages and transferring the sweepings into some road or travelled track. Their idea is that unless the disease is communicated to some person who will take it on to the next village, the plague will not leave them. For this reason they do not throw the sweepings into the jungle, as no one passes that way, and consequently the benefit of sweeping is lost.32

An extraordinary case was recently reported from the Dehra Ismâîl Khân District. There had been a good deal of sickness in the village, and the people spread a report that this was due to the fact that a woman, who had died some seven months previously, had been chewing her funeral sheet. The relatives were asked to allow the body to be examined, which was done, and it was found that owing to the subsidence of the ground through rain, some earth had fallen into the mouth of the corpse. A copper coin was placed in the mouth as a viaticum, and a fowl killed and laid on the body, which was again interred. The same result is very often believed to follow from burying persons of the sweeper caste in the usual extended position, instead of a sitting posture or with the face downwards.

A sweeper being one of the aboriginal or casteless tribes is believed to have something uncanny about him. Recently in Muzaffarnagar, a corpse buried in the unorthodox way was disinterred by force, and the matter finally came before the courts.

The Demon of Cattle Disease

In the same way cattle disease is caused by the plague demon. Once upon a time a man, whose descendants live [145]in the Mathura District, was sleeping out in the fields when he saw the cattle disease creeping up to his oxen in an animal shape. He watched his opportunity and got the demon under his shield, which he fixed firmly down. The disease demon entreated to be released, but he would not let it go till it promised that it would never remain where he or his descendants were present. So to this day, when the murrain visits a village, his descendants are summoned and work round the village, calling on the disease to fulfil its contract.33

The murrain demon is expelled in the same way as that of the cholera, and removed by the agency of the scapegoat. In the western part of the North-Western Provinces you will often notice wisps of straw tied round the trunks of acacia trees, which, as we shall see, possess mystic powers, as a means to bar disease.

Kâsi Bâba is the tribal deity of the Binds of Bengal. Of him it is reported: “A mysterious epidemic was carrying off the herds on the banks of the Ganges, and the ordinary expiatory sacrifices were ineffectual. One evening a clownish Ahîr, on going to the river, saw a figure rinsing its mouth from time to time, and making an unearthly sound with a conch shell. The lout, concluding that this must be the demon that caused the epidemic, crept up and clubbed the unsuspecting bather. Kâsi Nâth was the name of the murdered Brâhman, and as the cessation of the murrain coincided with his death, the low Hindustâni castes have ever since regarded Kâsi Bâba as the maleficent spirit that sends disease among the cattle. Nowadays he is propitiated by the following curious ceremony.

As soon as an infectious disease breaks out, the village cattle are massed together, and cotton seed sprinkled over them. The fattest and sleekest animal being singled out, is severely beaten with rods. The herd, scared by the noise, scamper off to the nearest shelter, followed by the scape bull; and by this means it is thought the murrain is stayed.”34 [146]

Kâsi Dâs, according to the last census, has 172,000 worshippers in the eastern districts of the North-Western Provinces.

Other Cholera Godlings

Beside Hardaul Lâla, the great cholera godling, Hulkâ Devî, the impersonation of vomiting, is worshipped in Bengal with the same object. She appears to be the same as Holikâ or Horkâ Maiyyâ, whom we shall meet in connection with the Holî festival. We have already noticed Marî or Marî Mâî, “Mother death,” or as she is called when promoted to Brâhmanism, Marî Bhavânî. She and Hatthî, a minor cholera goddess, are worshipped when cholera prevails. By one account she and Sîtalâ are daughters of Râja Vena.

About ten thousand people recorded themselves at the last census as worshippers of Hatthî and Marî in the North-Western Provinces. Among the jungle tribes of Mirzapur she is known as Obâ, an Arabic word (waba) meaning pestilence. Marî, as we have said, has a special shrine in Sultânpur to commemorate a fatal outbreak of cholera in the army of Safdar Jang. In the Panjâb Marî is honoured with an offering of a pumpkin, a male buffalo, a cock, a ram and a goat. These animals are each decapitated with a single blow before her altar. If more than one blow is required the ceremony is a failure. Formerly, in addition to these five kinds of offering a man and woman were sacrificed, to make up the mystic number seven.35

Exorcism of Disease

The practice of exorcising these demons of disease has been elaborated into something like a science. Disease, according to the general belief of the rural population, can be removed by a species of magic, usually of the variety known as “sympathetic,” and it can be transferred from the sufferer to some one else.

The special incantations for [147]disease are in the hands of low-caste sorcerers or magicians. Among the more primitive races, such as those of Drâvidian origin in Central India, this is the business of the Baiga, or aboriginal devil priest. But even here there is a differentiation of function, and though the Baiga is usually considered competent to deal with the cases of persons possessed of evil spirits, it is only special persons who can undertake the regular exorcism. This is among the lower tribes of Hindus the business of the Syâna, “the cunning man,” the Sokha (Sanskrit sukskma, “the subtile one”), or the Ojha, which is a corruption of the Sanskrit Upâdhyâya or “teacher.”

Like Æsculapius, Paieon, and even Apollo himself, the successful magician and healer gradually develops into a god. All over the country there are, as we have seen, the shrines of saints who won the reverence of the people by the cures wrought at their tombs. The great deified healer in Behâr and the eastern Districts of the North-Western Provinces is Sokha Bâba, who, according to the last census, had thirteen thousand special worshippers. He is said to have been a Brâhman who was killed by a snake, and now possesses the power of inflicting snake-bite on those who do not propitiate him.

Exorcisers are both professional and non-professional. “Non-professional exorcisers are generally persons who get naturally improved by a guardian spirit (deva), and a few of them learn the art of exorcism from a Guru or teacher. Most of the professional exorcisers learn from a Guru. The first study is begun on a lunar or on a solar eclipse day. On such a day the teacher after bathing, and without wiping his body, or his head or hair, puts on dry clothes, and goes to the village godling’s temple.

The candidate then spreads a white cloth before the god, and on one side of the cloth makes a heap of rice, and on another a heap of Urad (phaseolus radiatus), sprinkles red lead on the heaps, and breaks a cocoanut in front of the idol. The Guru then teaches him the incantation (mantra), which he commits to memory. An ochre-coloured flag is then tied to a staff in [148]front of the temple, and the teacher and candidate come home.

“After this, on the first new moon which falls on a Saturday, the teacher and the candidate go together out of the village to a place previously marked out by them on the boundary. A servant accompanies them, who carries a bag of Urad, oil, seven earthen lamps, lemons, cocoanuts, and red powder. After coming to the spot, the teacher and the candidate bathe, and then the teacher goes to the village temple, and sits praying for the safety of the candidate. The candidate, who has been already instructed as to what should be done, then starts for the boundary of the next village, accompanied by the servant.

On reaching the village boundary, he picks up seven pebbles, sets them in a line on the road, and after lighting a lamp near them, he worships them with flowers, red powder, and Urad. Incense is then burnt, and a cocoanut is broken near the pebble which represents Vetâla and his lieutenants, and a second cocoanut is broken for the village godling.” Here the cocoanut is symbolical of a sacrifice which was probably originally of a human victim.

“When this is over, he goes to a river, well, or other bathing place, and bathes, and without wiping his body or putting on dry clothes, proceeds to the boundary of the next village. There he repeats the same process as he did before, and then goes to the boundary of a third village. In this manner he goes to seven villages and repeats the same process. All this while he keeps on repeating incantations. After finishing his worship at the seventh village, the candidate returns to his village, and going to the temple, sees his teacher and tells him what he has done.

“In this manner, having worshipped and propitiated the Vetâlas of seven villages, he becomes an exorcist. After having been able to exercise these powers, he must observe certain rules. Thus, on every eclipse day he must go to a sea-shore or a river bank, bathe in cold water, and while standing in the water repeat incantations a number of times. After bathing daily he must neither wring his head hair, nor [149]wipe his body dry. While he is taking his meals, he should leave off if he hears a woman in her monthly sickness speak or if a lamp be extinguished.

“The Muhammadan methods of studying exorcism are different from those of the Hindus. One of them is as follows:—The candidate begins his study under the guidance of his teacher on the last day of the lunar month, provided it falls on a Tuesday or Sunday. The initiation takes place in a room, the walls and floor of which have been plastered with mud, and here and there daubed with sandal paste.

On the floor a white sheet is spread, and the candidate after washing his hands and feet, and wearing a new waist-cloth or trousers, sits on the sheet. He lights one or two incense sticks and makes offerings of a white cloth and meat to one of the principal Musalmân saints. This process is repeated for from fourteen to forty days.”36

Few rural exorcisers go through this elaborate ritual, the object of which it is not difficult to understand. The candidate wishes to get the Vetâla or local demon of the village into his power and to make him work his will. So he provides himself with a number of articles which, as we shall see, are known for their influence over the spirits of evil, such as the Urad pulse, lamps, cocoanuts, etc. The careful rule of bathing, the precautions against personal impurity, the worship done at the shrine of the village godling by the teacher, are all intended to guard him in the hour of danger.

The common village “wise man” contents himself with learning a few charms of the hocus pocus variety, and a cure in some difficult case of devil possession secures his reputation as a healer.

Methods of Rural Exorcism

The number of these charms is legion, and most exorcisers have one of their own in which they place special confidence and which they are unwilling to disclose. As Sir Monier Williams writes37:—“No magician, wizard, sorcerer or witch [150]whose feats are recorded in history, biography or fable, has ever pretended to be able to accomplish by incantation and enchantment half of what the Mantra-sâstri claims to have power to effect by help of his Mantras.

For example, he can prognosticate futurity, work the most startling prodigies, infuse breath into dead bodies, kill or humiliate enemies, afflict any one anywhere with disease or madness, inspire anyone with love, charm weapons and give them unerring efficacy, enchant armour and make it impenetrable, turn milk into wine, plants into meat, or invert all such processes at will. He is even superior to the gods, and can make goddesses, gods, imps and demons carry out his most trifling behests.

Hence it is not surprising that the following remarkable saying is everywhere current throughout India: ‘The whole universe is subject to the gods; the gods are subject to the Mantras; the Mantras to the Brâhmans; therefore the Brâhmans are our gods.’”

All these devices of Mantras or spells, Kavâchas or amulets, Nyâsas or mentally assigning various parts of the body to the protection of tutelary presiding deities, and Mudras or intertwining of the fingers with a mystic meaning, spring from the corrupt fountain head of the Tantras, the bible of Sâktism. But these are the speciality of the higher class of professional exorciser, who is very generally a Brâhman, and do not concern us here.

A few examples of the formulæ used by the village “cunning man” may be given here. Thus in Mirzapur when a person is known to be under the influence of a witch the Ojha recites a spell, which runs—“Bind the evil eye; bind the fist; bind the spell; bind the curse; bind the ghost and the churel; bind the witch’s hands and feet. Who can bind her? The teacher can bind her. I, the disciple of the teacher, can bind her. Go, witch, to wherever thy shrine may be; sit there and leave the afflicted person.”

In these spells Hanumân, the monkey godling, is often invoked. Thus—“I salute the command of my teacher. Hanumân, the hero, is the hero of heroes. He has in his quiver nine lâkhs of arrows. He is sometimes on the right, sometimes [151]on the left, and sometimes in the front. I serve thee, powerful master. May not this man’s body be crippled. I see the cremation ground in the two worlds and outside them. If in my body or in the body of this man any ill arise, then I call on the influence of Hanumân.

My piety, the power of the teacher, this charm is true because it comes from the Almighty.” In the same way two great witches, Lonâ Chamârin and Ismâîl the Jogi are often invoked. The Musalmân calls on Sulaimân, the lord Solomon, who is a leader of demons and a controller of evil spirits, for which there is ample authority in the Qurân.

But it is in charms for disease that the rural exorciser is most proficient. Accidents, such as the bites of snakes, stings of scorpions, or wasps are in particular treated in this way, and these charms make up most of the folk-medicine of Northern India. Thus, when a man is stung by a scorpion the exorciser says—“Black scorpion of the limestone! Green is thy tail and black thy mouth. God orders thee to go home. Come out! Come out! If thou fail to come out Mahâdeva and Pârvatî will drive thee out!” Another spell for scorpion sting runs thus—“On the hill and mountain is the holy cow.

From its dung the scorpions were born, six black and six brown. Help me! O Nara Sinha! (the man lion incarnation of Vishnu). Rub each foot with millet and the poison will depart.” So, to cure the bite of a dog, get some clay which has been worked on a potter’s wheel, which as we shall see is a noted fetish, make a lump of it and rub it to the wound and say—“The black dog is covered with thick hair.” Another plan in cases of hydrophobia is to kill a dog, and after burning it to make the patient imbibe the smoke.

Headache is caused by a worm in the head, which comes out if the ear be rubbed with butter. Women of the gipsy tribes are noted for their charms to take out the worm which causes toothache. When a man is bitten by a snake the practitioner says—“True god, true hero, Hanumân! The snake moves in a tortuous way. The male and female weasel come out of their hole to destroy it. Which poison will they devour? First they will eat the black Karait snake, [152]then the snake with the jewel, then the Ghor snake.

I pray to thee for help, my true teacher.” So, if you desire to be safe from the attacks of the tiger, say—“Tie up the tiger, tie up the tigress, tie up her seven cubs. Tie up the roads and the footpaths and the fields. O Vasudeva, have mercy? Have mercy, O Lonâ Chamârin!” Lastly, if you desire an appointment, say—“O Kâlî, Kankâlî, Mahâkâli! Thy face is beautiful, but at thy heart is a serpent. There are four demon heroes and eighty-four Bhairons. If thou givest the order I will worship them with betel nuts and sweetmeats. Now shout—‘Mercy, O Mother Kali!’” It would not be difficult to describe hundreds of such charms, but what has been recorded will be sufficient to exemplify the ordinary methods of rural exorcism.38

When the Ojha is called in to identify the demon which has beset a patient, he begins by ascertaining whether it is a local ghost or an outsider which has attacked him on a journey. Then he calls for some cloves, and muttering a charm over them, ties them to the bedstead on which the sick man lies.

Then the patient is told to name the ghost which has possessed him, and he generally names one of his dead relations, or the ghost of a hill, a tree or a burial ground. Then the Ojha suggests an appropriate offering, which when bestowed and food given to Brâhmans, the patient ought in all decency to recover. If he does not, the Ojha asserts that the right ghost has not been named, and the whole process is gone through again, if necessary funds are forthcoming.

The Baiga of Mirzapur, who very often combines the function of an Ojha with his own legitimate business of managing the local ghosts, works in very much the same way. He takes some barley in a sieve, which as we shall see is a very powerful fetish, and shakes it until only a few grains are left in the interstices. Then he marks down the intruding ghost by counting the grains, and recommends the sacrifice of a fowl or a goat, or the offering of some liquor, [153]most of which he usually consumes himself. If his patient die, he gets out of the difficulty by saying—“Such and such a powerful Bhût carried him off.

What can a poor man, such as I am, do?” If a tiger or a bear kills a man, the Baiga tells his friends that such and such a Bhût was offended because no attention was paid to him, and in revenge entered into the animal which killed the deceased, the obvious moral being that in future more regular offerings should be made through the Baiga.

In Hoshangâbâd the Bhomka sorcerer has a handful of grain waved over the head of the sick man. This is then carried to the Bhomka, who makes a heap of it on the floor, and sitting over it, swings a lighted lamp suspended by four strings from his fingers. He then repeats slowly the names of the patient’s ancestors and of the village and local godling, pausing between each, and when the lamp stops spinning the name at which it halts is the name to be propitiated.

Then in the same way he asks—“What is the propitiation offering to be? A pig? A cocoanut? A chicken? A goat?” And the same mystic sign indicates the satisfaction of the god.39

The Kol diviner drops oil into a vessel of water. The name of the deity is pronounced as the oil is dropped. If it forms one globule in the water, it is considered that the particular god to be appeased has been correctly named; if it splutters and forms several globules, another name is tried.

The Orâon Ojha puts the fowls intended as victims before a small mud image, on which he sprinkles a few grains of rice; if they pick at the rice it indicates that the particular devil represented by the image is satisfied with the intentions of his votaries, and the sacrifice proceeds.40

The Panjâb diviner adopts a stock method common to such practitioners all over the world. He writes some spells on a piece of paper, and pours on it a large drop of ink. Flowers are then placed in the hands of a young child, who is told to look into the ink and say, “Summon the four [154]guardians.” He is asked if he sees anything in the ink, and according to the answer a result is arrived at.41 The modus operandi of these exorcisers is, in fact, very much the same in India as in other parts of the world.42

Exorcisim

Exorcism by Dancing

In all rites of this class religious dancing as a means of scaring the demon of evil holds an important place. Thus of the Bengal Muâsis Col. Dalton writes43—“The affection comes on like a fit of ague, lasting sometimes for a quarter of an hour, the patient or possessed person writhing and trembling with intense violence, especially at the commencement of the paroxysm.

Then he is seen to spring from the ground into the air, and a succession of leaps follow, all executed as though he were shot at by unseen agency. During this stage of the seizure he is supposed to be quite unconscious, and rolls into the fire, if there be one, or under the feet of the dancers, without sustaining injury from the heat or from the pressure. This lasts for a few minutes only, and is followed by the spasmodic stage. With hands and knees on the ground and hair loosened, the body is convulsed, and the head shakes violently, whilst from the mouth issues a hissing or gurgling noise.

The patient next evincing an inclination to stand on his legs, the bystanders assist him, and place a stick in his hand, with the aid of which he hops about, the spasmodic action of the body still continuing, and the head performing by jerks a violently fatiguing circular movement. This may go on for hours, though Captain Samuells says that no one in his senses could continue such exertion for many minutes. When the Baiga is appealed to to cast out the spirit, he must first ascertain whether it is Gansâm or one of his familiars that has possessed the victim.

If it be the great Gansâm, the [155]Baiga implores him to desist, meanwhile gradually anointing the victim with butter; and if the treatment is successful, the patient gradually and naturally subsides into a state of repose, from which he rises into consciousness, and, restored to his normal state, feels no fatigue or other ill-effects from the attack.”

The same religious dance of ecstasy appears in what is known as the Râs Mandala of the modern Vaishnava sects, which is supposed to represent the dance of the Gopîs with Krishna. So in Bombay among the Marâthas the worship of the chief goddess of the Dakkhin, Tuljâ Bhavânî, is celebrated by a set of dancing devotees, called Gondhalis, whose leader becomes possessed by the goddess.

A high stool is covered with a black cloth. On the cloth thirty-six pinches of rice are dropped in a heap, and with them turmeric and red powder, all scarers of demons, are mixed. On the rice is set a copper vessel filled with milk and water, and in this the goddess is supposed to take her abode. Over it are laid betel leaves and a cocoanut. Five torches are carried round the vessel by five men, each shouting “Ambâ Bhavânî!”

The music plays, and dancers dance before her. So at a Brâhman marriage at Pûna the boy and girl are seated on the shoulders of their maternal uncles or other relations, who perform a frantic dance, the object being, as in all these cases, to scare away the spirits of evil.44

Flagellation

So with flagellation, which all over the world is supposed to have the power of scaring demons. Thus in the Central Indian Hills the Baiga with his Gurda, or sacred chain, which being made of iron, possesses additional potency, soundly thrashes patients attacked with epilepsy, hysteria, and similar ailments, which from their nature are obviously due to demoniacal agency.

There are numerous instances of the use of the lash for this purpose. In Bombay, among the Lingâyats, the woman who names the child has her [156]back beaten with gentle blows; and some beggar Brâhmans refuse to take alms until the giver beats them.45 There is a famous shrine at Ghauspur, in the Jaunpur District, where the Ojhas beat their patients to drive out the disease demon.46 The records of Roman Catholic hagiology and of the special sect of the Flagellants will furnish numerous parallel instances.

Treatment of Sorcerers

While the sorcerer by virtue of his profession is generally respected and feared, in some places they have been dealt with rather summarily. There is everywhere a struggle between the Brâhman priest of the greater gods and the exorciser, who works by the agency of demons. Sudarsan Sâh rid Garhwâl of them by summoning all the professors of the black art with their books. When they were collected he had them bound hand and foot and thrown with their books and implements into the river.

The same monarch also disposed very effectually of a case of possession in his own family. One day he heard a sound of drumming and dancing in one of his courtyards, and learnt that a ghost named Goril had taken possession of one of his female slaves. The Râja was wroth, and taking a thick bamboo, he proceeded to the spot and laid about him so vigorously that the votaries of Goril soon declared that the deity had taken his departure.

The Râja then ordered Goril to cease from possessing people, and nowadays if any Garhwâli thinks himself possessed, he has only to call on the name of Sudarsan Sâh and the demon departs.47

Appointment of Ojhas

The mode of succession to the dignity of an Ojha varies in different places. In Mirzapur the son is usually educated by his father, and taught the various spells and modes of [157]incantation. But this is not always the case; and here at the present time the institution is in a transition stage. South of the Son we have the Baiga, who usually acts as an Ojha also; and he is invariably drawn from the aboriginal races. Further north he is known as Nâya (Sanskrit nâyaka) or “leader.” Further north, again, as we leave the hilly country and enter the completely Brâhmanized Gangetic valley, he changes into the regular Ojha, who is always a low-class Brâhman.

In one instance which came under my own notice, the Nâya of the village had been an aboriginal Kol, and he before his death announced that “the god had sat on the head” of a Brâhman candidate for the office, who was duly initiated, and is now the recognized village Ojha. This is a good example of the way in which Brâhmanism annexes and absorbs the demonolatry of the lower races.

This, too, enables us to correct a statement which has been made even by such a careful inquirer as Mr. Sherring when he says48—“Formerly the Ojha was always a Brâhman; but his profession has become so lucrative that sharp, clever, shrewd men in all the Hindu castes have taken to it.” There can be no question that the process has been the very reverse of this, and that the early Ojhas were aboriginal sorcerers, and that their trade was taken over by the Brâhman as the land became Hinduized.

In Hoshangâbâd the son usually succeeds his father, but a Bhomka does not necessarily marry into a Bhomka family, nor does it follow that “once a Bhomka, always a Bhomka.” On the contrary, the position seems to be the result of the special favour of the godling of the particular village in which he lives; and if the whole of the residents emigrate in a body, then the godling of the new village site will have to be consulted afresh as to the servant whom he chooses to attend upon him.

“If a Bhomka dies or goes away, or a new village is established, his successor is appointed in the following way. [158]All the villagers assemble at the shrine of Mutua Deo, and offer a black and white chicken to him. A Parihâr, or priest, should be enticed to grace the solemnity and make the sacrifice, but if that cannot be done the oldest man in the assembly does it. Then he sets a wooden grain measure rolling along the line of seated people, and the man before whom it stops is marked out by the intervention of the deity as the new Bhomka.”49

It marks perhaps some approximation to Hinduism that the priest, when inspired by the god, wears a thread made of the hair of a bullock’s tail, unless this is based on the common use of thread or hair as a scarer of demons, or is some token or fetish peculiar to the race. At the same time the non-Brâhmanic character of the worship is proved by the fact that the priest, when in a state of ecstasy, cannot bear the presence of a cow, or Brâhman. “The god,” they say, “would leave their heads if either of these came near.”

On one occasion, when Sir C. A. Elliott saw the process of exorcism, the men did not actually revolve when “the god came on his head.” He covered his head up well in a cloth, leaving space for the god to approach, and in this state he twisted and turned himself rapidly, and soon sat down exhausted. We shall see elsewhere that the head is one of the chief spirit entries, and the top of the head is left uncovered in order to let the spirit make its way through the sutures of the skull.

Then from the pit of his stomach he uttered words which the bystanders interpreted to direct a certain line of conduct for the sick man to pursue. “But perhaps the occasion was not a fair test, as the Parihâr strongly objected to the presence of an unbeliever, on the pretence that the god would be afraid to come before so great an official.” This has always been the standing difficulty in Europeans obtaining a practical knowledge of the details of rural sorcery, and when a performance of the kind is specially arranged, it will usually be found that the officiant performs the introductory rites with comparative [159]success, but as it comes to the crucial point he breaks down, just as the ecstatic crisis should have commenced.

This is always attributed to the presence of an unbeliever, however interested and sympathetic. The same result usually happens at spiritualistic séances, when anyone with even an elementary knowledge of physics or mechanics happens to be one of the audience.

Fraud in Exorcism

The question naturally arises—Are all these Ojhas and Baigas conscious hypocrites and swindlers? Dr. Tylor shrewdly remarks that “the sorcerer generally learns his time-honoured profession in good faith, and retains the belief in it more or less from first to last. At once dupe and cheat, he combines the energy of a believer with the cunning of a hypocrite.”50 This coincides with the experience of most competent Indian observers. No one who consults a Syâna and observes the confident way in which he asserts his mystic power, can doubt that he at least believes to a large extent in the sacredness of his mission.

Captain Samuells, who repeatedly witnessed these performances, distinctly asserts that it is a mistake to suppose that there is always intentional deception.51

Charms

Disease Charms

Next to the services of the professional exorciser for the purpose of preventing or curing disease, comes the use of special charms for this purpose. There is a large native literature dealing with this branch of science. As a rule most native patients undergo a course of this treatment before they visit our hospitals, and the result of European medical science is hence occasionally disappointing.

One favourite talisman of this kind is the magic square, which consists in an arrangement of certain numbers in a special [160]way. For instance, in order to cure barrenness, it is a good plan to write a series of numbers which added up make 73 both ways on a piece of bread, and with it feed a black dog, which is the attendant of Bhairon, a giver of offspring. To cure a tumour a figure in the form of a cross is drawn with three cyphers in the centre and one at each of the four ends.

This is prepared on a Sunday and tied round the left arm. Another has a series of numbers aggregating 15 every way. This is engraved on copper and tied round a child’s neck to keep off the Evil Eye. In the case of cattle disease, some gibberish, which pretends to be Arabic or Sanskrit, appealing for the aid of Lonâ Chamârin or Ismâîl Jogi, with a series of mystic numbers, is written on a piece of tile. This is hung on a rope over the village cattle path, and a ploughshare is buried at the entrance to make the charm more powerful.

When cattle are attacked with worms, the owner fills a clean earthen pot with water drawn from the well with one hand; he then mutters a blessing, and with some sacred Dâbh grass sprinkles a little water seven times along the back of the animal.

The number of these charms is legion. Many of them merge into the special preservatives against the Evil Eye, which will be discussed later on. Thus the bâzâr merchant writes the words Râm! Râm! several times near his door, or he makes a representation of the sun and moon, or a rude image of Ganesa, the godling of good luck, or draws the mystical Swâstika. A house of a banker at Kankhal which I recently examined bore a whole gallery of pictures round it.

There were Siva and Pârvatî on an ox with their son Mârkandeya; Yamarâja, the deity of death, with a servant waving a fan over his head; Krishna with his spouse Râdhâ: Hanumân, the monkey godling; the Ganges riding on a fish, with Bhâgîratha, who brought her down from heaven; Bhîshma, the hero of the Mahâbhârata;

Arjuna representing the Pândavas; the saints Uddalaka and Nârada Muni; Ganesa with his two maidservants; and Brahma and Vishnu riding on Sesha Nâga, the great serpent. [161]Beneath these was an inscription invoking Râma, Lakshmana, the Ganges and Hanumân.

Rag Offerings

Next come the arrangements by which disease may be expelled or transferred to someone else. In this connection we may discuss the curious custom of hanging up rags on trees or near sacred wells. Of this custom India supplies numerous examples. At the Balchha pass in Garhwâl there is a small heap of stones at the summit, with sticks and rags attached to them, to which travellers add a stone or two as they pass.52 In Persia they fix rags on bushes in the name of the Imâm Raza.

They explain the custom by saying that the eye of the Imâm being always on the top of the mountain, the shreds which are left there by those who hold him in reverence, remind him of what he ought to do in their behalf with Muhammad, ’Ali and the other holy personages, who are able to propitiate the Almighty in their favour.53 Moorcroft in his journey to Ladâkh describes how he propitiated the evil spirit of a dangerous pass with the leg of a pair of worn-out nankin trousers.54 Among the Mirzapur Korwas the Baiga hangs rags on the trees which shade the village shrine, as a charm to bring health and good luck.

These rag shrines are to be found all over the country, and are generally known as Chithariyâ or Chithraiyâ Bhavânî, “Our Lady of Tatters.” So in the Panjâb the trees on which rags are hung are called Lingrî Pîr or the rag saint.55

The same custom prevails at various Himâlayan shrines and at the Vastra Harana or sacred tree at Brindaban near Mathura, which is now invested with a special legend, as commemorating the place where Krishna carried off the clothes of the milkmaids when they were bathing, an incident which constantly appears in both European and Indian folk-lore.56 In Berâr a heap of stones daubed with [162]red and placed under a tree fluttering with rags represents Chindiya Deo or “the Lord of Tatters,” where, if you present a rag in due season, you may chance to get new clothes.57 The practice of putting or tying rags from the person of the sick to a tree, especially a banyan, cocoanut, or some thorny tree, is prevalent in the Konkan, but not to such an extent as that of fixing nails or tying bottles to trees.

In the Konkan, when a person is suffering from a spirit disease, the exorcist takes the spirit away from the sick man and fixes it in a tree by thrusting a nail in it. We have already had an example of this treatment of ghosts by the Baiga. Sometimes he catches the spirit of the disease in a bottle and ties the bottle to a tree.58 In a well-known story of the Arabian Knights the Jinn is shut up in a bottle under the seal of the Lord Solomon.

There have been various explanations of this custom of hanging rags on trees.59 One is that they are offerings to the local deity of the tree. Mr. Gomme quotes an instance of an Irishman who made a similar offering with the following invocation: “To St. Columbkill—I offer up this button, a bit o’ the waistband o’ my own breeches, an’ a taste o’ my wife’s petticoat, in remembrance of us havin’ made this holy station; an’ may they rise up in glory to prove it for us in the last day.”

He “points to the undoubted nature of the offerings and their service, in the identification of their owners—a service which implies their power to bear witness in spirit-land to the pilgrimage of those who deposited them during lifetime at the sacred well.” Some of the Indian evidence seems to show that these rags are really offerings to the sacred tree. Thus, Colonel Tod60 describes the trees in a sacred grove in Râjputâna as decorated with shreds of various coloured cloth, “offerings of the traveller to the forest divinity for protection against evil spirits.”

This usage often merges [163]into actual tree-worship, as among the Mirzapur Patâris, who, when fever prevails, tie a cotton string which has never touched water round the trunk of a Pîpal tree, and hang rags from the branches. So, the Kharwârs have a sacred Mahua tree, known as the Byâhi Mahua or “Mahua of marriage,” on which threads are hung at marriages. At almost any holy place women may be seen winding a cotton thread round the trunk of a Pîpal tree.