Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: Biography

From: The Times of India

From: The Times of India

From: From: The Times of India

From: From: The Times of India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

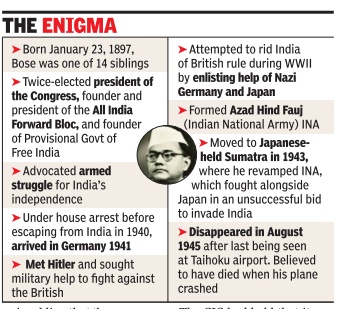

An overview

Devika Sethi’s book/ Excerpts

Devika Sethi, August 14, 2023: The Times of India

Devika Sethi’s book Censored: What the British Raj Didn’t Want Us to Read dives into the history of sedition and censorship in colonial India. Closely examining 100 texts that the British Empire banned, censored or deemed seditious, the work brings to life lost gems from India’s freedom, cultural and social movements. Here’s an excerpt from the chapter featuring revolutionary leader Subhas Chandra Bose.

Having joined and resigned from the Indian Civil Service (1920-21), and having served as Congress president in the 1930s, Subhas Chandra Bose (1897-1945) charted his own path during the Second World War. He sought alliances with Britain’s enemies in that war, Japan and Germany, in order to hasten Indian independence.

He formed the Provisional Government of Free India (in Japanese-occupied Singapore in October 1943) and revived the Azad Hind Fauj (Indian National Army) with the help of Indian prisoners-of-war in Southeast Asia. He retains hold of the popular imagination in India even today, and remains a central figure in what-if (counterfactual) histories pivoting on a hypothetical India had it been led by Bose.

The excerpt comes from a book by Bose that was banned in 1935 (Bose later expanded it in 1942). Given that much is made of his differences with Gandhi today, the excerpt is a wonderfully revealing account of Bose’s appreciation for Gandhi and impatience with Gandhian methods. Another excerpt from the same book contains his explanations for the appeal of revolutionary methods in Bengal. The second excerpt is from a banned book that reprinted the transcripts of Bose’s radio addresses.

The two speeches are reprinted in entirety. In one, from 1942, Bose addresses the Indian people and criticises the methods of Congress. In the other, from 1944, he addresses Gandhi with warmth and affection, and explains why he himself needed to leave India and seek help from abroad.

The Indian Struggle, 1920-34

In early January 1935, after carefully examining the over 350-page manuscript of Bose’s book (which had been seized by the police at Karachi), the Government of India (Delhi) communicated to the Secretary of State for India (London) their view that it was necessary to ban the entry of the book in India.

The reasons for doing so were many: the book’s object was to show that the British connection was undesirable; it accused the British of driving a wedge between Hindus and Muslims; it argued that left-wing methods were more successful than right-wing ones; and it took the line that all acts of terrorism were acts of retaliation in response to government excesses.

In other words, the Government of India thought that the work justified terrorism, and would therefore ‘encourage terrorist methods or methods of direct action’. The Secretary of State concurred, and import of the book into India was banned on 21 January 1935 under the Sea Customs Act.

The next month, after a question was asked in the British House of Commons about the ban on the book, the Secretary of State for India stated that he had read the book himself, that it was banned because it encouraged terrorism and direct action, and that in the matter of the ban he had to trust the opinion of ‘the men on the spot’, as they would be victims of violence if it occurred.

The same month, the Government of India too was asked in the Legislative Assembly about the reason for banning Bose’s book. Was it not the case, asked Pandit Nilakantha Das, that the book contained only historical analysis, and was not the government aware that there was a belief that the book was banned only as ‘a measure of harassment’?

Das also asked the Government of India to explain what it deemed objectionable in the book. In response, Sir Henry Craik (home member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council) replied that the book had been banned — as had previously been mentioned in the House of Commons by the Secretary of State for India — because it ‘tended generally to encourage terrorism or direct action’.

In March the same year, the Government of India was again asked questions about the book by other members of the Legislative Assembly; one Indian member, Seth Govind Das, even went on to suggest that ‘all books that are considered worth having in this country are generally proscribed by the government of this country’.

Gandhi's role in Indian history

The role which a man plays in history depends partly on his physical and mental equipment, and partly on the environment and the needs of times in which he is born. There is something in Mahatma Gandhi, which appeals to the mass of the Indian people. Born in another country he might have been a complete misfit. What, for instance, would he have done in a country like Russia or Germany or Italy? His doctrine of non-violence would have led him to the cross or to the mental hospital. In India it is different. His simple life, his vegetarian diet, his goat’s milk, his day of silence every week, his habit of squatting on the floor instead of sitting on a chair, his loin-cloth — in fact everything connected with him — has marked him out as one of the eccentric Mahatmas of old and has brought him nearer to his people.

Wherever he may go, even the poorest of the poor feels that he is a product of the Indian soil — bone of his bone, flesh of his flesh. When the Mahatma speaks, he does so in a language that they comprehend not in the language of Herbert Spencer and Edmund Burke, as for instance Sir Surendra Nath Banerji would have done, but in that of the Bhagavad Gita and the Ramayana.

When he talks to them about Swaraj, he does not dilate on the virtues of provincial autonomy or federation, he reminds them of the glories of Rama-Rajya (the kingdom of King Rama of old) and they understand. And when he talks of conquering through love and ahimsa (non-violence), they are reminded of Buddha and Mahavira and they accept him.

But the conformity of the Mahatma’s physical and mental equipment to the traditions and temperament of the Indian people is but one factor accounting for the former’s success. If he had been born in another epoch in Indian history, he might not have been able to distinguish himself so well.

For instance, what would he have done at the time of the revolution of 1857 when the people had arms, were able to fight and wanted a leader who could lead them in battle? The success of the Mahatma has been due to the failure of constitutionalism on the one side and armed revolution on the other…

The Indian National Congress of today is largely his creation. The Congress constitution is his handiwork. From a talking body he has converted the Congress into a living and fighting organisation. It has its ramification in every town and village in India, and the entire nation has been trained to listen to one voice.

Nobility of character and capacity to suffer have been made the essential tests of leadership, and the Congress is today the largest and the most representative political organisation in the country. But how could he achieve so much within this short period? By his single-hearted devotion, his relentless will and his indefatigable labour. Moreover, the time was auspicious and his policy prudent. Though he appeared as a dynamic force, he was not too revolutionary for the majority of his countrymen. If he had been so, he would have frightened them, instead of inspiring them; repelled them, instead of drawing them.

His policy was one of unification. He wanted to unite the Hindu and Moslem; the high caste and the low caste; the capitalist and the labourer; the landlord and the peasant. By this humanitarian outlook and his freedom from hatred, he was able to rouse sympathy even in his enemy’s camp.

But Swaraj is still a distant dream. Instead of one, the people have waited for 14 long years. And they will have to wait many more. With such purity of character and with such an unprecedented following, why has the Mahatma failed to liberate India? He has failed because the strength of a leader depends not on the largeness — but on the character — of one’s following. With a much smaller following, other leaders have been able to liberate their country — while the Mahatma with a much larger following has not. He has failed, because while he has understood the character of his own people — he has not understood the character of his opponents.

The logic of the Mahatma is not the logic which appeals to John Bull. He has failed, because his policy of putting all his cards on the table will not do. We have to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s — and in a political fight, the art of diplomacy cannot be dispensed with. He has failed, because he has not made use of the international weapon. If we desire to win our freedom through non-violence, diplomacy and international propaganda are essential.

He has failed, because the false unity of interests that are inherently opposed is not a source of strength but a source of weakness in political warfare. The future of India rests exclusively with those radical and militant forces that will be able to undergo the sacrifice and suffering necessary for winning freedom… Excerpted with permission from Censored: What the British Raj Didn’t Want Us to Read (published by Roli Books).

Women's regiment

The Times of India, June 20, 2016

In 1943, Bose raised a women's regiment to fight British

Is the participation of women in the military a recent development?

From ancient warriors, to medieval queens and women archers of the Amazon rainforests, there is plenty of evidence of women's active participation in the military through the ages. In the decades following the industrial revolution, women's participation in the armed forces was discouraged in the Western world. In many countries colonised by the West, however, there were women fighting against the colonial powers. After the industrial revolution, the first large-scale mobilisation of women for military purposes happened during the First World War. Even at that time, their role was primarily restricted to nursing services and other support functions.

Since when have women been recruited for combat roles?

During the Second World War, both sides, the Allies and the Axis powers, recruited women soldiers -most of which was voluntary. The UK, Germany and the Soviets had the bulk of women soldiers fighting in the war. In the UK and Germany, the role of women was largely confined to administrative, clerical and nursing jobs. The limited combat role open to them was the running of anti-aircraft systems.The Soviet Union, on the other hand, was the first major country to recruit women for front-line combat positions. Soviet sniper Lyudmila Mikhailivna Pavlichenko was credited with 309 kills in the Second World War.Similarly, Roza Shanina operated on the front line in a marksman's position during the war, and was credited with 59 confirmed kills. The Soviet Union al so had an all-women fighter pilot regiment popularly known as the `Night Witches'. The 40-member regiment flew over 23,000 sorties during the war. In 1943, Subhas Chandra Bose's Indian National Army raised the all-women Rani of Jhansi regiment to operate as guerilla infantry to fight against the British.

What is the present scenario?

Official recognition of women as full-fledged members of the armed forces gained momentum in the late 1940s. Women became officially recognised as a permanent part of the US armed forces in 1948, the UK in 1949, and Canada in 1951.In most other countries, the first batch of women soldiers joined in the 1980s or the 1990s. India started recruiting women in its armed forces in 1992.Initially, these recruitments were largely restricted to the Army Medical Corps, the Army Dental Corps, and the Military Nursing Service. In some countries like New Zealand, Israel and Canada, all military positions, including combat roles, are open for women.Others have certain restrictions.

Since when are women flying fighter planes?

On record, Turkey is the first country to allow a woman to fly a fighter plane. In 1937, former Turkish president Mustafa Kemal Ataturk's adopted daughter Sabiha Gokcen became the world's first combat pilot when she took part in the military operation against the Dersim rebellion. In 1989, Dee Brasseur and Jane Foster qualified as the first female fighter pilots of the Canadian air force. In 1993, Jeannie Leavitt became the first female combat pilot of the American air force. In 2012, Leavitt became the world's first female wing commander of any major air force when she was promoted to command 5,000 airmen at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in North Carolina. In 2013, China, too, inducted 16 female fighter pilots in its air force. On Saturday, the Indian Air Force formally commissioned its first women fighter pilots with the induction of Bhawana Kanth, Avani Chaturvedi and Mohana Singh.

Personal life

Srirupa Ray , January 24, 2023: The Times of India

KOLKATA: Emilie Schenkl led a tough life even as her husband, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, remained engaged in his quest for India’s freedom, said their daughter Anita Bose Pfaff.

In an exclusive conversation with TOI on the eve of Netaji’s 126th birth anniversary, Bose Pfaff said: “His first and foremost, and almost only, interest was his fight for his country’s freedom. My mother had to suffer because of this as she always had to play second fiddle. Whatever time they got together could only be sort of taken away from his first and most important love that was his country.”

“At that time, it was not uncommon in my generation — and in Europe, where I lived — for children my age to grow up without a father, because I was born during World War II. In my generation, there were a number of children whose fathers had been soldiers and either got killed or became a prisoner of war,” said the Austria-born economist. Now 80, Bose Pfaff recalls growing up without her father around. “You had many single mothers, fending for themselves and their children at the time. I wished I had a father who was there and who would care for me. I had my mother and maternal grandmother, who certainly did very much for me. I was taken care of well. But, of course, one misses a father too, particularly as a teenager as one grows up and sort of breaks away from the parents.”

Schenkl would tell her stories about Netaji’s escapades, how they worked together when she was his secretary, and the little time they spent with each other. “My father saw me when I was four weeks old, I do not remember that. My mother over the years told some stories about him,” Bose Pfaff said.

“One story I can recall was when my father was in Vienna in the 1930s. The Prince of Wal-es, the later King, was visiting Vienna and my father was considered a dangerous person. Police shadowed him and he took the opportunity to drag them through the woods during a not-so-nice weather period. He was very fond of walking and so his shadows had to follow him all th-rough woods. He eventually returned to the city and dashed for a tram, hopped onto it and my mother was with him,” shesaid.

Bose Pfaff believes her father died in the plane crash in Taiwan on August 18, 1945. Last year, she petitioned the Centre for a DNA test to be conducted on the ashes preserved at Renkoji Temple in Japan which she believes are her father’s remains.

'INA Treasure'

Sources: India Today:

1. India Today

2. India Today

Sandeep Unnithan

May 15, 2015

Netaji files reveal Jawaharlal Nehru government knew of Subhas Chandra Bose's missing treasure chest

Locked away in the vaults of South Block and protected by the Official Secrets Act for over half a century, are revelations of one of India's earliest scandals. Hundreds of yellowing documents that raise serious suspicions about cash, gold and jewellery that Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose collected to finance his armed struggle for Independence being siphoned away.

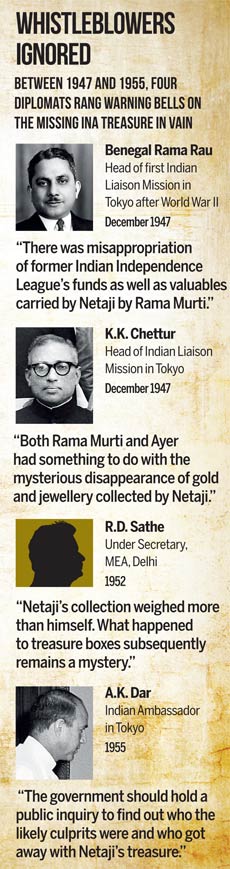

One of the 37 secret 'Netaji files' in the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) and Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) deals with the 'INA Treasure'. Built over the years with secret reports, letters and frantic telegrams, it deals with a story of suspected rank greed and opportunism which overcame Indian freedom fighters as they looted the treasury of the collapsed Provisional Government of Azad Hind (PGAH). This suspected loot took place soon after Bose's demise in a plane crash in 1945. But the startling twist is not about the missing Indian National Army (INA) treasure worth several hundred crores of rupees today. It is that the government of the day knew about it but did nothing. Classified papers obtained by INDIA TODAY reveal that the Nehru government ignored repeated warnings from three mission heads in Tokyo between 1947 and 1953. R.D. Sathe, an under secretary (later foreign secretary) in the MEA, wrote a stark warning to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, also the foreign minister, in 1951 that a bulk of the treasure - gold ornaments and precious stones - had been left behind by Bose in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), Vietnam. This treasure, Sathe concluded, had already been disposed of by the suspected conspirators.

All these warnings were ignored. No inquiry was ordered. Worse, one of the former INA men these diplomats suspected of embezzlement was rewarded with a government sinecure.

On April 13, Surya Kumar Bose , Netaji's grandnephew met Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Berlin just three days after an India Today expose revealed this snooping. The family's outrage has now given way to a resolute demand for declassification of over 150 'Netaji files' still held by the government. On May 9, the Prime Minister assured Bose family members of declassification. "Don't call it a people's demand, it is the nation's duty," Modi told family members in Kolkata. But as these extraordinary revelations, some of them mentioned in author Anuj Dhar's 2012 book, India's Biggest Cover-Up, show the government has had much to hide.

On January 29, 1945, Indian residents of Rangoon, the capital of Japaneseoccupied-Burma, held a grand weeklong ceremony. It was the 48th birthday of Netaji, the head of the provisional government of the Azad Hind. It was a birthday quite unlike any other.

Netaji, the iron patriot who coined the slogan "Jai Hind" and exhorted his troops to march to Delhi, was weighted against gold, "somewhat to his distaste", Hugh Toye notes in his biography The Springing Tiger: The Indian National Army and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. Over Rs 2 crore worth of donations were collected that week including more than 80 kg of gold.

Fund collection drives were not new to the INA. Netaji wanted his two-year-old government-in-exile to depend as little on the Japanese for financing his soldiers. He turned to an estimated two million Indians in erstwhile British colonies conquered by his Japanese allies.

He relied on the sheer dint of his personality, emotive speeches and unswerving commitment to Indian independence to ask the community for funds. "After he spoke," writes Madhusree Mukherjee in her 2010 book Churchill's Secret War, "housewives would come up and strip their arms and necks of gold to serve the cause of freedom". At one such impassioned fund-raising public meeting in Rangoon on August 21, 1944, newspapers of the day recalled, Hiraben Betani gave away 13 of her gold necklaces worth Rs 1.5 lakh and Habib Sahib, a multi-millionaire, gifted away all his property worth over Rs 1 crore to the Netaji Fund. Another INA funder, Rangoon-based businessman V.K. Chelliah Nadar, deposited Rs 42 crore and 2,800 gold coins in the Azad Hind Bank.

Netaji had raised the largest war chest by any Indian leader in the 20th century. But by 1945, this was to no avail as the Japanese army and the INA crumpled in the face of a resurgent Allied thrust into Burma. It was only a matter of time before Rangoon, headquarters of the Azad Hind Bank and the springboard for the leap into India, fell to the Allies. Netaji retreated to Bangkok on April 24, 1945, carrying with him the treasury of the provisional government. There are conflicting accounts on how much gold he took.

Dinanath, chairman of the Azad Hind Bank interrogated by British intelligence soon after the war, said Netaji left with 63.5 kg of gold. Debnath Das, head of the Indian Independence League (IIL) in Bangkok, told the Shah Nawaz Committee of inquiry in 1956 that Netaji withdrew treasure worth Rs 1 crore, mostly ornaments and gold bars in 17 small sealed boxes. General Jagannath Rao Bhonsle of the INA also told the Committee that Netaji brought gold ornaments and cash packed in six steel boxes.

On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers. The 40,000-strong INA also surrendered to the Allied forces in Burma, their officers marched off to the Red Fort to face trial for treason.

A terrible fate awaited the first Indian in nearly a century to lead an insurrection against the British empire. Netaji had been marked for assassination by Winston Churchill in 1941 and in 1945, had told his aides he would be "lined up against a brick wall and shot" if captured. On August 18, Netaji, along with his aide Habibur Rahman, boarded a Japanese bomber in Saigon bound for Manchuria, where he would attempt to enter the Soviet Union.

Habibur Rahman recounted the last hours of Netaji before the Shah Nawaz Committee in 1956. Netaji had been injured in the plane crash but his uniform, soaked in aviation fuel, caught fire, grievously injuring him. He died in a Japanese army hospital six hours after the air crash.

Also destroyed in the aircraft were two leather attaches, each 18 inches long, packed with INA gold. Japanese armymen posted at the airbase gathered around 11 kg of the remnants of the treasure, sealed them in a petrol can and transported it to the Imperial Japanese Army headquarters in Tokyo. A second box held the remains of Netaji's body that had been cremated in a local crematorium in Taiwan.

The two containers came to represent two of modern India's biggest political mysteries: the fate of Netaji and the whereabouts of his treasure. Where was the rest of Netaji's war chest? It beggared belief that over 63.5 kg of treasure could have turned into a 11 kg lump of charred jewellery.

Exact numbers were hard to come by in the melee of defeat. The INA and the Japanese destroyed documents to prevent them falling into Allied hands, further confusing the picture. Inquiry commissions relied on eyewitness accounts to build a picture of the INA treasure.

An 18-page secret note, prepared for the Morarji Desai government in 1978, quotes Netaji's personal valet Kundan Singh as saying that the treasure was in "four steel cases which contained articles of jewellery commonly worn by Indian women, chains of ladies watches, necklaces, bangles, bracelets, earrings, pounds and guineas and some gold wires". It also included a gold cigarette case gifted to him by Adolf Hitler. These boxes were checked before Netaji departed from Bangkok to Saigon. A leader of the IIL in Bangkok, Pandit Raghunath Sharma, said that Netaji took with him gold and valuables worth over Rs 1 crore. There was clearly much more of the treasure than the two leather suitcases burnt in the airplane crash. One man who knew this was S.A. Ayer, a former journalist-turned-publicity minister in the Azad Hind government.

Ayer was with Netaji during his last few days. On August 22, 1945, he flew from Saigon to Tokyo and joined M. Rama Murti, former president of the IIL in Tokyo, to receive two boxes from the Japanese army. They deposited Netaji's ashes with the Renkoji temple in Tokyo. Murti kept the treasure. On August 25, 1946, Lt-Colonel John Figgess, a military counterintelligence officer posted in the headquarters of the Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia, submitted a report to his superior Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Figgess, whose 1997 obituary credited him with "the successful emasculation of the pro-Japanese Indian National Army formed and led by Subhas Chandra Bose", concluded that Netaji had indeed died in the plane crash in Formosa (now Taiwan).

The warnings from Tokyo

On December 4, 1947, Sir Benegal Rama Rau, the first head of the Indian liaison mission in Tokyo, made a startling allegation. In a letter written to the MEA, Rau alleged that Murti had embezzled IIL funds and misappropriated the valuables carried by Netaji. The ambassador's letter was prompted by complaints from local Indians. Japanese media at the time reported how Rama Murti and his younger brother J. Murti lived in affluence and rode in two sedans, an unusual sight in war-ravaged Japan. The formal reply that the president of the Indian Association in Tokyo got from the mission was that the Indian government could not interest itself in the INA funds. The government became interested in the INA treasure only four years later, in May 1951, when an exceptionally persistent diplomat, K.K. Chettur, headed the Indian liaison mission in Tokyo-India was yet to establish full-fledged diplomatic relations with Japan.

Chettur noted with dismay the return of Ayer. He was now a director of publicity with the government of Bombay state. Now, seven years later, Ayer was going back to Tokyo on what he claimed was a holiday but actually with a secret agenda. In a series of back-and-forth cables to the foreign office in New Delhi, Chettur also made the first mention of a phrase "INA treasure". From then on, this phrase stuck in government use.

Ayer told Chettur in Tokyo that he had been entrusted twin tasks by the government of India: to verify whether the ashes kept in the Renkoji temple were those of Netaji and to retrieve the gold jewellery that had been recovered from the crashed aircraft. In a secret dispatch to the MEA, Chettur said that local Indians were "seething with anger at the return of Ayer and his association with these two brothers (the Murtis)" as "both Rama Murti and Ayer had something to do with the mysterious disappearance of the gold and jewellery collected by Netaji".

But Ayer had already pulled a rabbit out of his hat. He informed Chettur that part of the INA treasure had survived and had been in Rama Murti's custody since 1945. In October 1951, the Indian embassy collected the remnants of the INA treasure from Rama Murti's residence. Ambassador Chettur still disbelieved the Ayer-Rama Murti story. In a cable to New Delhi he relayed his apprehensions. Chettur believed that Ayer, apprehensive of an early conclusion of the Peace Treaty in 1945, had come to Tokyo to "divide the loot" and draw a red herring across the trail by handing over a small quantity of gold to the government.

In one of his final communications to New Delhi on June 22, 1951, Chettur offered to probe the disappearance of the "Netaji collections". The first comprehensive warning of foul play in the INA treasure followed just months later. It was a two-page secret note authored by R.D. Sathe on November 1, 1951. "INA Treasures and their handling by Messrs Iyer and Ramamurthi" summed up the story: considerable quantities of gold and treasures were given to the late Subhas Chandra Bose by Indians in the Far East as part of their war effort; all that was left of it was 11 kg of gold and 3 kg of gold mixed with molten iron and 300 grams of gold brought by Ayer from Saigon to Tokyo in 1945. Rama Murti had been questioned several times by Indian officials but had denied the existence of the treasure. Ayer's activities in Japan were suspicious, Sathe said. "What is still more important is that the bulk of the treasure was left in Saigon and it is significant from information that is available that on the 26th January, 1945, Netaji's collection weighed more than himself." Sathe pointed at Ayer's movements from Saigon to Tokyo, an eyewitness who claimed to have seen the boxes in his room. "What happened to these boxes subsequently is a mystery as all that we have got from Ayer is 300 gram of gold and about 260 rupees." Sathe also flagged a relationship that had baffled most Indians in Japan.

Rama Murti's proximity to British intelligence officer Lt-Col Figgess. He was now posted as a British liaison officer at General Douglas MacArthur's occupation headquarters in Tokyo. What was the glue that held Colonel Figgess and his erstwhile INA foes together? Sathe's letter has one conjecture. "Suspicion regarding the improper disposal of the treasure is thickened by the comparative affluence in 1946 of Mr Ramamurthy when all other Indian nationals in Tokyo were suffering the greatest hardships. Another fact which suggests that the treasures were improperly disposed of is the sudden blossoming out into an Oriental curio expert of Col Figgess, the Military Attaché of the British Mission in Tokyo and the reported invitation extended by the Colonel to Ramamurthy to settle down in UK."

This note was signed by Jawaharlal Nehru on November 5, 1951. "PM has seen this note. This may be placed on the relevant file," then foreign secretary Subimal Dutt signed off on it. Prime Minister Nehru's thoughts that year were clearly about the first Indian General Election that began in October that year. The Congress was set to sweep the elections. There was no charismatic opposition leader. The fate of Subhas Chandra Bose was still unclear. Rumours suggested he could still be alive, ready to return to India as a possible challenger only fuelled the government's doubt-one of the probable reasons the Intelligence Bureau had the family members under surveillance.

Conclusive evidence that Netaji had died in the air crash could help silence government critics. This evidence came from Ayer. On September 26, 1951, Nehru wrote to Foreign Secretary Dutt that Ayer had met him with an inquiry report. Ayer, Nehru wrote, "was dead sure that there was no doubt at all about Shri Subhas Chandra Bose's death on the occasion".

It now turns out that Chettur's suspicions were correct. Ayer was on a covert mission for the government. In 1952, Prime Minister Nehru quoted from Ayer's report in Parliament affirming that Netaji had indeed died in an air crash in Taipei. The INA treasure, or what was left of it, was secretly brought into India from Japan. It was inspected by Nehru who called it a "poor show". There was a debate within his cabinet on what to do with it. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the education minister, suggested the gold be given to Netaji's family. Nehru overruled the suggestion. The Bose family had not accepted Netaji's death in an air crash, he said. Besides, the burnt jewellery should be preserved by the government since it was some evidence of the aircraft accident and subsequent fire. The jewellery was sealed and consigned to the vaults of the National Museum, then located in the Rashtrapati Bhavan .

The following year, Ayer was appointed adviser, integrated publicity programme, for Nehru's Five Year Plan. The case was closed. Or was it? The warnings from the Indian mission in Japan continued to pour in. In 1955, A.K. Dar, the ambassador in Tokyo, made another explosive accusation. In a four-page secret note sent to South Block, Dar again demanded a public inquiry which if it would not get back the treasure would at least determine who the likely culprits were and who did away with it.

Dar mentioned the "disinterested attitude of the Government of India for almost 10 years" because "it not only helped the guilty parties concerned to escape without blame but also because it postpones the rendering of honour to one of the great leaders who gave his life for the independence of the country".

More warnings but no action

The INA Treasure papers throw up more questions than answers. A retired diplomat who studied the papers is unable to understand why the government did not order an inquiry. "If we had suspicions that the treasure was looted, the government should have leaned on the Allied Powers then running Japan to order an inquiry," he says.

PM Nehru was in the loop on most INA matters and was quick to intervene in other cases where former INA men sought to cash in on their wartime fortune. In a November 1952 letter signed by B.N. Kaul, principal private secretary to the PM, Nehru directed the Central Board of Revenue not to refund Rs 28 lakh recovered from five INA special forces men who had landed on the Orissa coast in a Japanese submarine in 1944. They were arrested by the British and the money, meant for subversive operations in India, confiscated from them. Nehru's silence on the fate of the INA treasure is baffling, especially since the Shah Nawaz Committee set up by him to probe Netaji's disappearance in 1956 also recommended an inquiry into the fate of it. It was impossible to conclude what had happened to the treasure, the committee noted and called an inquiry into all the assets of Netaji's government.

Two prominent Indians based in Japan who deposed before the one-man inquiry commission headed by Justice G.D. Khosla in 1971 also claimed the treasure had been embezzled. They told Justice Khosla about the sudden affluence of the Murtis in Japan. One of the witnesses, veteran Tokyo-based journalist K.V. Narain, asserted that Ayer had come to Japan with two suitcases of jewellery which he gave Rama Murti in 1945. In its report of June 30, 1974, the Khosla commission noted that part of the treasure had been misappropriated by Ram Murti and his brother J. Murti. But the commission could not find proof and felt the quest would not yield anything.

That the revelations within the 'INA Treasure' file is a ticking time bomb has been known to the government. In 2006, the government declassified one INA treasure file from the sensitive 'Not To Go Out' section of the PMO. File 23(11)/56-57 now placed in the National Archives is, however, scrubbed of any references to the angry reports from diplomats Chettur, Sathe and Dar. The file only speaks of the 11 kg of gold that survived the air crash, now in the National Museum.

"The loot of the INA treasure is free India's first scam, it predates the 1948 jeep scandal by one year. Its implications are far more horrendous as details on record suggest some sort of complicity on the part of Jawaharlal Nehru," alleges Anuj Dhar.

S.A. Ayer's Mumbai-based son Brigadier A. Thyagarajan (retired) rubbishes the speculation that his father had anything to do with the embezzlement of the INA treasure. My father came back to Mumbai after his fact-finding mission and started from scratch," he told india today. "He had no treasure. He had a large family of seven children to look after. When he died in 1980, he had a small bank balance with savings from his pension, he didn't own any property and lived in a rented apartment till his demise."

Netaji's grand-nephew and Trinamool Congress MP Sugata Bose says he is aware of Rama Murti being treated with suspicion by the Shah Nawaz Committee but dismisses reports linking Ayer to the missing treasure as "speculative". "I would be careful about making charges about anyone without credible evidence," he says.

J. Murti's son Anand J. Murti, who runs a chain of restaurants in Tokyo, is baffled by the allegations in the files. "What I remember being told is that when Netaji's cremated ashes and his molten luggage were brought to Tokyo by the Japanese military and received by Rama, he handed the luggage to Ayer and (Habibur) Rahman and took the ashes to a Buddhist temple in hiding from the Allied occupation forces."

That part of the INA treasure had been secretly transferred to Delhi in a secret operation was revealed only in the 1970s. In 1978, Subramanian Swamy, then a Janata Party MP, made a sensational public claim that the INA treasure had been embezzled by Prime Minister Nehru. In a letter written to Prime Minister Morarji Desai, he demanded an inquiry into the disappearance of the treasure and its covert transfer to India. Desai made a statement in Parliament later that year that part of the treasure had indeed been transferred to India. A secret report submitted to Desai's PMO by the MEA summed up all the facts of the case, beginning from Netaji's final journey to the arrival of part of the treasure to India. It included the role of Chettur, the whistleblower in the case, and the questionable conduct of Ayer and Rama Murti. The Morarji Desai government, however, did not order an inquiry. The INA treasure case was quickly forgotten. None of the key players are alive today, although some of their descendants still nurse the hope of reclaiming the fortune.

One of the last claimants to the INA treasure died in 2012. Ramalinga Nadar, the son of Rangoon-based businessman V.K. Chelliah Nadar, had petitioned the government for the Rs 42 crore and 2,800 gold coins which his father had deposited in the Azad Hind Bank in Rangoon in 1944. "In 2011, RBI officials told the Nadars they had nothing to do with the INA treasure and treated the matter as closed," says his son-in-law KKP Kamaraj.

Prime Minister Modi's promise of declassification has breathed life into an issue buried by successive governments. "Declassification of all government files is a must to dispel all the theories about Subhas Chandra Bose and clear mysteries like the disappearance of the INA Treasure," Netaji's grand-nephew and Bose family spokesperson Chandra Bose told India Today. The question remains as it has for over half a century- whether the government can handle the truth.

Treasure trove of secrets

Netaji was a somewhat late entrant into India's pantheon of freedom fighters. His portrait was unveiled in Parliament in 1978, possibly because it marred the Gandhian narrative of a non-violent freedom struggle. Over 2,000 INA soldiers who died fighting the British in Burma and the North-east were also sidestepped by history books. Over the years, the Bose legend has not only attracted admirers such as the LTTE's late chief Velupillai Prabhakaran but also a deluge of conspiracy theories. Bose was believed to have escaped to China and the Soviet Union, later returning to India where he lived as a 'baba' in Faizabad, UP, until his death in 1985. These theories were founded in his real-life escapades: Bose disguised as a Pathan to escape into Afghanistan, an Italian businessman to travel through Russia and finally hopped from a German submarine to a Japanese submarine in the Indian Ocean. The theories would have fizzled out but for the government's refusal to declassify the Netaji files.

"The fact that the files have not been declassified, when they should have been in the 1960s and 1970s, has only added to the Bose mystery," says Wajahat Habibullah. During his five-year stint as India's first chief information commissioner, Habibullah handled multiple requests for declassification of the Netaji files, all of which were turned down by the government.

Every government since Nehru's has told politicians, researchers and journalists that the contents of over 150 secret 'Netaji Files' are so sen- sitive that their revelations would create law and order problems, especially in West Bengal. Worse, they would "spoil India's relations with friendly foreign nations". The Modi government in 2014 deleted the law and order fallout of the revelations but maintained the official line. Responding to a query from Trinamool Congress MP Sukhendu Sekhar Roy, Minister of State for Home Affairs Haribhai Parthibhai Chaudhary said, in a written reply in the Rajya Sabha on December 17, 2014, declassification was "not desirable from the point of view of India's relations with other countries". Five Netaji files locked in the PMO are so secret that even their names have not been disclosed under the Right to Information Act.

What terrible state secrets sit in those files locked in the PMO? Secrets, which in the words of Roy, made Rajnath Singh go from an espouser of the truth to someone who "sat in the Lok Sabha, silently nodding his head while I asked for declassification".

"How can Netaji's death in an air crash be blamed on foreign countries?" Roy asks. "There are clearly some other reasons which both the BJP and Congress want to cover up."

Two of them, the Shah Nawaz Committee in 1956 and the Khosla Commission in 1974 said Netaji died in a plane crash. Their findings were rejected by then Prime Minister Morarji Desai in 1978. The Justice (M.K.) Mukherjee Commission's suggestion that Netaji had faked his death and had escaped to the Soviet Union was rejected by the UPA government in 2006.

Often, the inquiries have fuelled speculation. BJP leader Subramanian Swamy picks out the testimony of Shyam Lal Jain, Nehru's stenographer who deposed before the Khosla Commission in 1970. Jain swore he had typed out a letter which Nehru then sent to Stalin in 1945 in which he admitted knowing of Bose's captivity.

"The plane crash was a ruse. Netaji sought asylum in the Soviet Union where he was imprisoned and later killed by Stalin," Swamy claims. Bose family members, including Anita Bose-Pfaff, want reports lying with the Centre and state governments to be declassified. "A special investigative team with representatives from the PMO, foreign ministry, IB, CBI and historians need to research those papers and reveal to the public the story of Subhas Bose," says Chandra Kumar Bose. If the current revelations are anything to go by, the Netaji files could bring the curtains down on India's longest running political mystery.

Revelations

These explosive revelations are contained in 37-odd files which the PMO has refused to declassify for over a decade. The government line, that no public interest was served by declassification, now strains credulity: declassified papers in the National Archives show that the Nehru government initiated snooping on the Bose family and it lasted for two decades from 1947 to 1968.

On April 13, Surya Kumar Bose, Netaji's grandnephew met Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Berlin just three days after an INDIA TODAY exposé revealed this snooping.

On January 29, 1945, Indian residents of Rangoon, the capital of Japanese- occupied-Burma, held a grand week-long ceremony. It was the 48th birthday of Netaji, the head of the provisional government of the Azad Hind. Netaji was weighted against gold, "somewhat to his distaste", Hugh Toye notes in his biography.

The Springing Tiger: The Indian National Army and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. Over Rs.2 crore worth of donations were collected that week including more than 80 kg of gold. Netaji had raised the largest war chest by any Indian leader in the 20th century. But by 1945, this was to no avail as the Japanese army and the INA crumpled in the face of a resurgent Allied thrust into Burma. Netaji retreated to Bangkok on April 24, 1945, carrying with him the treasury of the provisional government. There are conflicting accounts on how much gold he took. Dinanath, chairman of the Azad Hind Bank interrogated by British intelligence soon after the war, said Netaji left with 63.5 kg of gold.

On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers. The 40,000-strong INA also surrendered to the Allied forces in Burma, their officers marched off to the Red Fort to face trial for treason.

On August 18, Netaji, along with his aide Habibur Rahman, boarded a Japanese bomber in Saigon bound for Manchuria, where he would attempt to enter the Soviet Union.

Habibur Rahman recounted the last hours of Netaji before the Shah Nawaz Committee in 1956. Netaji had been injured in the plane crash and died in a Japanese army hospital six hours after the crash. Also destroyed in the aircraft were two leather attachés, each 18 inches long, packed with INA gold. Japanese armymen posted at the airbase gathered around 11 kg of the remnants of the treasure, sealed them in a petrol can and transported it to the Imperial Japanese Army headquarters in Tokyo. A second box held the remains of Netaji's body that had been cremated in a local crematorium in Taiwan.

Where was the rest of Netaji's war chest? It beggared belief that over 63.5 kg of treasure could have turned into an 11 kg lump of charred jewellery.

An 18-page secret note, prepared for the Morarji Desai government in 1978, quotes Netaji's personal valet Kundan Singh as saying that the treasure was in "four steel cases". A leader of the IIL in Bangkok, Pandit Raghunath Sharma, said that Netaji took with him gold and valuables worth over Rs.1 crore. There was clearly much more of the treasure than the two leather suitcases burnt in the airplane crash. One man who knew this was S.A. Ayer, a former journalist-turned-publicity minister in the Azad Hind government. Ayer was with Netaji during his last few days. On August 22, 1945, he flew from Saigon to Tokyo and joined M. Rama Murti, former president of the IIL in Tokyo, to receive two boxes from the Japanese army. Murti kept the treasure.

On August 25, 1946, Lt-Colonel John Figgess, a military counterintelligence officer posted in the headquarters of the Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia, submitted a report to his superior Lord Louis Mountbatten. Figgess concluded that Netaji had indeed died in the plane crash in Formosa (now Taiwan).

On December 4, 1947, Sir Benegal Rama Rau, the first head of the Indian liaison mission in Tokyo, made a startling allegation. In a letter written to the MEA, Rau alleged that Murti had embezzled IIL funds and misappropriated the valuables carried by Netaji. The formal reply that the president of the Indian Association in Tokyo got from the mission was that the Indian government could not interest itself in the INA funds. The government became interested in the INA treasure only four years later, in May 1951, when diplomat, K.K. Chettur, headed the Indian liaison mission in Tokyo-India was yet to establish full-fledged diplomatic relations with Japan.

Chettur noted with dismay the return of Ayer. He was now a director of publicity with the government of Bombay state. Now, seven years later, Ayer was going back to Tokyo on what he claimed was a holiday but actually with a secret agenda.

Cable exchange

In a series of back-and-forth cables to the foreign office in New Delhi, Chettur also made the first mention of a phrase "INA treasure". Ayer told Chettur in Tokyo that he had been entrusted twin tasks by the government of India: to verify whether the ashes kept in the Renkoji temple were those of Netaji and to retrieve the gold jewellery that had been recovered from the crashed aircraft. In a secret dispatch to the MEA, Chettur said that local Indians were "seething with anger at the return of Ayer and his association with these two brothers (the Murthys)" because "both Ramamurthy and Ayer had something to do with the mysterious disappearance of the gold and jewellery collected by Netaji".

But Ayer had already pulled a rabbit out of his hat. He informed Chettur that part of the INA treasure had survived and had been in Rama Murti's custody since 1945. In October 1951, the Indian embassy collected the remnants of the INA treasure from Rama Murti's residence. Ambassador Chettur still disbelieved the Ayer-Rama Murti story. Chettur believed that Ayer had come to Tokyo to "divide the loot and salve his and Shri Ram Murthy's conscience by handing over a small quantity to the government, in the hope that by doing so, he would also succeed in drawing a red herring across the trail".

In one of his final communications to New Delhi on June 22, 1951, Chettur offered to probe the disappearance of the "Netaji collections".

The first comprehensive warning of foul play in the INA treasure followed just months later. It was a two-page secret note authored by R.D. Sathe on November 1, 1951. "INA Treasures and their handling by Messrs Iyer and Ramamurthi" summed up the story: considerable quantities of gold and treasures were given to the late Subhas Chandra Bose by Indians in the Far East as part of their war effort; all that was left of it was 11 kg of gold and 3 kg of gold mixed with molten iron and 300 grams of gold brought by Ayer from Saigon to Tokyo in 1945. Rama Murti had been questioned several times by Indian officials but had denied the existence of the treasure. Ayer's activities in Japan were suspicious, Sathe said. Sathe pointed at Ayer's movements from Saigon to Tokyo, an eyewitness who claimed to have seen the boxes in his room.

Sathe also flagged a relationship that had baffled most Indians in Japan. Rama Murti's proximity to British intelligence officer Lt-Col Figgess. He was now posted as a British liaison officer at General Douglas MacArthur's occupation headquarters in Tokyo.

What was the glue that held Colonel Figgess and his erstwhile INA foes together? Sathe's letter has one conjecture.

"Suspicion regarding the improper disposal of the treasure is thickened by the comparative affluence in 1946 of Mr Ramamurthy when all other Indian nationals in Tokyo were suffering the greatest hardships. Another fact which suggests that the treasures were improperly disposed of is the sudden blossoming out into an Oriental curio expert of Col Figges, the Military Attaché of the British Mission in Tokyo and the reported invitation extended by the Colonel to Ramamurthy to settle down in UK."

This note was signed by Jawaharlal Nehru on November 5, 1951. "PM has seen this note. This may be placed on the relevant file," then foreign secretary Subimal Dutt signed off on it.

Conclusive evidence that Netaji had died in the air crash could help silence government critics. This evidence came from Ayer. On September 26, 1951, Nehru wrote to Foreign Secretary Dutt that Ayer had met him with an inquiry report. Ayer, Nehru wrote, "was dead sure that there was no doubt at all about Shri Subhas Chandra Bose's death on the occasion".

It now turns out that Chettur's suspicions were correct. Ayer was on a covert mission for the government. In 1952, Nehru quoted from Ayer's report in Parliament affirming that Netaji had indeed died in an air crash in Taipei.

Secret operation

The INA treasure, or what was left of it, was secretly brought into India from Japan. It was inspected by Nehru who called it a "poor show". There was a brief debate within his cabinet on what to do with it. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the education minister, suggested the gold be given to Netaji's family. Nehru overruled the suggestion. The jewellery was sealed and consigned to the vaults of the National Museum in Delhi.

The following year, Ayer was appointed adviser, integrated publicity programme, for Nehru's Five Year Plan. The case was closed. Or was it?

The warnings from the Indian mission in Japan continued to pour in. In 1955, A.K. Dar, the ambassador in Tokyo, made another explosive accusation. In a four-page secret note sent to South Block, Dar again demanded a public inquiry which if it would not get back the treasure would at least determine who the likely culprits were and who did away with it.

In a November 1952 letter signed by B.N. Kaul, principal private secretary to the PM, Nehru directed the Central Board of Revenue not to refund Rs.28 lakh recovered from five INA special forces men who had landed on the Orissa coast in a Japanese submarine in 1944. They were arrested by the British and the money, meant for subversive operations in India, confiscated from them. Nehru's silence on the fate of the INA treasure is baffling, especially since the Shah Nawaz Committee set up by him to probe Netaji's disappearance in 1956 also recommended an inquiry into the fate of it. It was impossible to conclude what had happened to the treasure, the committee noted and called an inquiry into all the assets of Netaji's government. That the revelations within the 'INA Treasure' file is a ticking time bomb has been known to the government. In 2006, the government declassified one INA treasure file from the sensitive 'Not To Go Out' section of the PMO.

File 23(11)/56-57 now placed in the National Archives is, however, scrubbed of any references to the angry reports from diplomats Chettur, Sathe and Dar. The file only speaks of the 11 kg of gold that survived the air crash, now in the National Museum.

The declassification ball is now clearly in the government's court. "It is necessary for the people of India to know the truth," Netaji's grandnephew Surya Kumar Bose told INDIA TODAY. "Whether it is good or bad for Netaji, we don't know. But the truth must emerge."

The Times of India’s reports on Netaji

The Times of India, Sep 19 2015

Some 40,000 diehard India lovers men and women flung themselves into the jaws of death more than 70 years ago. About half of them died, many fighting in the trenches, several of starvation, others of malaria and diseases. The INA was on a near-impossible mission a 5,000-km march from Singapore to liberate their motherland from the British their inspiration Netaji. Subhas was on TOI's radar, as a fast-rising Congress leader & even as CEO of the Calcutta Corporation

THE CEO

Mr Bose stated that of 93 vacancies, 35 had been filled of which 25 were filled with Muslims“ | July 18, 1924 edition reporting his address as CEO defending the need to give due representation to all communities while making appointments

THE LEADER

“In the first place,“ Bose said, “we should realize the world today is a unified whole... fate of India is linked with that of the rest of the modern world.“

Making his disapproval of Fascism clear, he said: “Imperialism, in whichever form it may appear, is a menace... It may appear in the cloak of democracy as in Western Europe, or in the garb of Fascist dictatorship as in Central Europe. As lovers of freedom and peace, we have resolutely to set our face against it.“

Report on Bose's address at Kolkata's Sraddhananda Park (April 7, 1937)

THE MYSTERY

“Mr Bose suddenly disappears: Calcutta mystery“ “Mystery prevails in Calcutta at the sudden disappearance last night of Mr Subhas Chandra Bose from his room where he had been confined since his release from jail in the first week of December. The additional chief presidency magistrate...has issued a warrant for his arrest. For the last few days Mr Bose was observing strict silence and had not been seeing anybody and he had been spending time in religious practices. As desired by Mr Bose, no member of his family entered his room throughout Saturday, nor did he send for anyone on that day. Bo This caused Mr. Times of Indi l Newsp anxiety among members The ProQues t Historica of his family pg. 7 and on Sunday afternoon on entering his room, they could not find Mr Bose on his bed.“

January 27, 1941 edition

THE LIBERATION ARMY

“...An attempt in which Bose has probably taken a large part has been made to form an Indian force on military lines to assist the Japanese,“ says Sir Reginald Maxwell, the home member. “The statements of PoWs...Leave little doubt that the latter have attempted to force Indian PoWs to perform duties outside the sanction of international law...The force includes Indian personnel forcibly converted from their allegiance“

First mention of Bose's effort to raise an army Nov 11, 1943

DURING WWII

“Bose's army meeting its doom“ Story datelined Calcutta: “Bose's Azad Hindusthan Army is meeting its doom in Burma. When the Japanese were fighting around Imphal in March 1944, it was repeatedly stated by Japanese broadcasts that the Azad Hindustan Army with Bose at its head, was about to strike on Indian soil.First news of the intended formation of such an army came to India in 1942, when Bose was stated to have gone over to the Japanese, and stated to be broadcasting from Tokio Radio.“

Report May 11, 1945

Vignettes

Swadhin Bharat Hindu Hotel

January 24, 2023: The Times of India

On Monday, a “hotel” at Kolkata’s College Street served ‘puisaag-er chochchori’ (a Bengali dish prepared with a medley of vegetables and pui saag in a mustard gravy), to its customers for free. But, for this popular “pice hotel” located at Bhawani Dutta Lane, this complimentary dish was not just another offer to attract customers. Rather, it is now a tradition at Swadhin Bharat Hindu Hotel, which the three generations of owners of this 110-year-old eatery (95 years at its present address) have rigorously followed as a “small and humble tribute” to the legendary freedom fighter, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, on his birthday every year.

See also

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: Biography

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: Ideology

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: After-1945