Mysore State: Economy, 1909

This article was written between 1907- 1909 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

From Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1907 – 1909

Mysore State (Maisūr): 1909

Contents |

Famines

Failure of the rains for three seasons in succession brought about the famine of 1876-8, and, in general, failure of the rains in any part is the main cause of famine. Those parts which receive the least rainfall are therefore the most liable to suffer: namely, Chitaldroog District, and the northern parts of Tumkūr, Bangalore, and Kolār Districts.

Rāgi is the staple food of all the labouring classes, and if this crop fails there is widespread distress. A remedial measure is the raising of crops of jola on the dry beds of tanks, but this is only a partial palliative. If the rāgi season has passed, horse-gram is more extensively sown for human food, but this will not mature without some rain.

Rāgi used formerly to be stored in underground pits, where it would keep good for ten years, to be brought out for consumption in times of scarcity. But the inducements now presented by high prices elsewhere and cheap means of transport have interfered with the replenishment of such stores, and consequently there is less resource of that kind to fall back upon. Rice, which is the main irrigated crop, is not much eaten except by Brāhmans, but always commands a ready sale for export.

The information about famines due to drought previous to that mentioned above is very scanty, but dreadful famines followed the devastations of the Marāthā armies and the wars with Mysore at the end of the eighteenth century. During the invasion of Lord Cornwallis, when, as Buchanan-Hamilton says, the country was attacked on all sides and penetrated in every direction by hostile armies, or by defending armies little less destructive, one-half at least of the inhabitants perished of absolute want.

In the last century periods of scarcity occurred in 1824, 1831, and 1833. The ten years following 1851 were a time of great trial, when year after year the sparse and ill-timed rainfall kept the agricultural classes in constant dread of actual want. Two or three seasons ensued which were prosperous, but in 1866 famine was again present in Chitaldroog and the north-eastern parts of the State.

Bad, however, as these seasons were, and critical as was the condition of the country, the misfortune which was to come put them completely in the shade. The failure of rain in the years 1875-7 brought about a famine such as was never known before.

The beginning of the calamity was the partial failure of the rains in 1875, the fall being from one-third to two-thirds of the average. Much of the food-crop was lost ; but owing to the usual large stocks in the State, only temporary or occasional distress was caused, for the price of grain did [S. 227] not rise to double the ordinary rates. In 1876 the rainfall was again very short, and barely a third of the ordinary harvest was reaped.

Matters were aggravated by the fact that crops had failed in the adjacent Districts of Madras and Bombay ; and by the middle of December famine had begun. From then till March matters grew worse. The only railway, from Madras to Bangalore, brought in daily 500 tons of food (enough to support 900,000 people), yet the prices of food ranged during those months at four to five times the ordinary rates. In April and May, 1877, the usual spring showers fell, and hope revived.

But as the month of June wore on and July came, it was apparent that the early rains were going to fail again, for the third year in succession. Panic and mortality spread among the people ; famine increased and became sore in the land. In May 100,000 starving paupers were being fed in relief kitchens, but by August the numbers rose to 227,000, besides 60,000 employed on the railway to Mysore city. It became evident that the utmost exertions of the local officers were unequal to cope with the growing distress. The Viceroy, Lord Lytton, visited Mysore, and appointed Mr. (now Sir) Charles Elliott as Famine Commissioner, with a large staff of European assistants.

Relief works were now concentrated, and gratuitous relief was confined to those whose condition was too low to expect any work from them at all. Bountiful rains in September and October caused the cloud to lift, and the pressure of famine began to abate. During the eight months of extreme famine no crops were reaped ; the price of grain ranged from three to six times the ordinary rates, and for the common people there were no means of earning wages outside the relief works.

Even in 1877-8 the yield of the harvest was less than half the crop of an ordinary year. From November, 1877, throughout 1878, prices stood at nearly three times the rate of ordinary years. The mortality in this famine has been estimated at 1¼ millions in a population of 5 1/3 millions. Taking the ordinary mortality at 24 per 1,000 per annum, this was raised to nearly fivefold, while a mean annual birth-rate of 36 per 1,000 was reduced to one-half.

The principal protective measures thus far successfully taken have been the extension of railways, so as to admit of the import and distribution of food-grains to all parts, and the extension of irrigation and other facilities for increasing cultivation. Plans for suitable relief works are also kept in readiness to be put into operation at the first appearance of necessity arising from scarcity.

Adminsitration

His Highness the Mahārājā is the head of the State, having been invested with full powers on attaining his majority in 1902. In his name, and subject to his sanction, the administration is carried on by the Dīwān or prime minister, who is assisted by two Councillors. The Chief Court is the highest tribunal [S. 228] of justice, and is composed of a bench of three Judges, headed by the Chief Judge. There is a secretariat staff for the transaction of official business, and Commissioners and other departmental officers at the head of the various branches of the administration, with a Comptroller for finance and treasury affairs.

The dynastic capital is at Mysore city, but the administrative head-quarters are at Bangalore. The Mahārājā resides for part of the year at each of these places, but the higher offices of the State are located at Bangalore. The Representative Assembly meets once a year at Mysore at the time of the Dasara festival, when the Dīwān delivers his annual statement of the condition of the finances and the measures of the State, after which suggestions by the members are considered.

The administrative divisions of the State are eight in number, called Districts, with an average area of 3,679 square miles, and an average population of 692,425. They are Bangalore, Kolār, Tumkūr, Mysore, Hassan, Kadūr, Shimoga, and Chitaldroog. Each of these is named after its head-quarters, except Kadūr District, the head-quarters of which are at Chikmugalūr. Mysore is the largest District and Hassan the smallest.

The chief officer in charge of a District is the Deputy-Commissioner, who is assisted by a staff of Assistant Commissioners. The subdivisions of a District are tāluks, altogether 69 in number, averaging eight or nine to each District1, with an average area of 427 square miles. These are formed into convenient groups of two, three, or four, which are distributed, under the authority of the Deputy-Commissioner, among the various Assistants and himself in such a way as to facilitate the dispatch of business and train the junior officers for administrative duties.

1 Kadūr has only five, while Mysore has fourteen, and Kolār ten.

The officer in charge of a tāluk is the amaldār, assisted by a sheristadār, who has charge of the treasury and acts as his deputy in case of need. Large tāluks have a portion divided off into a sub-tāluk under the charge of a deputy-amaldār, but with no separate treasury. A tāluk is composed of hobalis or hoblis, the average number being six to ten. In each of these is a shekdār, or revenue inspector.

The headman of a village is the pātel, a gauda or principal farmer, who is assisted in revenue collections by the shānbhog, a Brāhman accountant. These offices are hereditary, and form part of the village corporation of twelve, called ayagār in Kanarese and bāra balūti in Marāthī. The other members of this ancient institution are the Kammar or blacksmith, the Badagi or carpenter, the Agasa or washerman, the Panchāngi or Joyisa, an astrologer and calendar maker, the Nāyinda or barber, the Mādiga or cobbler and leather-dresser, the Kumbar or potter, the Talāri or watchman, and the Nirganti or distributor [S. 229] of water for irrigation.

The dozen is made up in some parts by including the Akkasāle or goldsmith ; in other parts his place is taken by the poet, who is also the schoolmaster. The respective duties of these village officials are definitely fixed ; and their services are remunerated either by the grant of rent-free lands, or by contributions, on a certain scale, of grain, straw, &c., at harvest time.

The Excise Commissioner is also Inspector-General of Registration. The number of sub-registry offices in 1904 was So, of which 59 were special, or with paid establishments, the remainder being in charge of tāluk revenue officers. The number of documents registered from 1881 to 1890 averaged 21,747; from 1891 to 1900, 46,251; and in 1904 the number was 57,637.

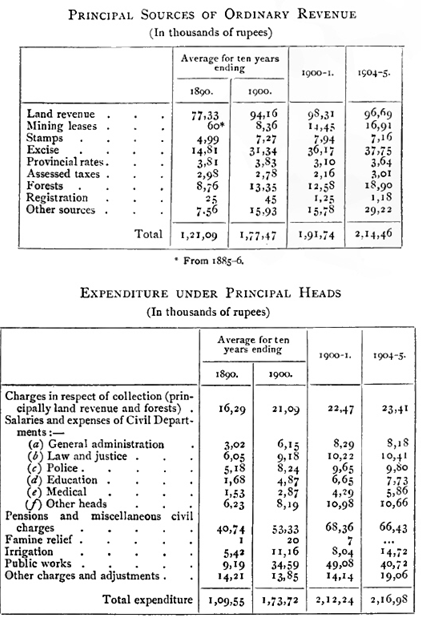

In addition to the local audits, the State accounts have been examined at various times by auditors deputed by the Government Finance The revenue under all heads has risen.

The increase under land is due to extension of cultivation. Since 1885 mining leases and the royalty on gold-production have added a new item to the revenue. The increase under excise is due mainly to an improved system of control, but also to a larger consumption arising from higher wages and the influx to the Gold Fields, and from the employment on railways, public works, and coffee plantations of classes with drinking habits. The decrease under land customs and assessed taxes is due to these duties having been transferred to municipalities wherever they exist.

The only customs retained by the State are on areca-nuts, the bulk of which are the produce of Kadūr and Shimoga Districts. An increase under forests took place owing to a revival of the market for sandal-wood, and to a greater supply of sleepers for railways. Subsequently the war between China and Japan temporarily crippled one of the principal sandal-wood [S. 231] markets, and not only did the demand for railway sleepers cease with the completion of the lines, but coal began to be substituted for wood as fuel for the engines. Since 1902 a substantial return has been received from the Cauvery Power installation for supplying electricity to the gold-mines.

Industries, handicrafts. textiles

For cotton-weaving the loom is placed over a kind of well or hole, large enough to contain the lower portion of the machinery, which is worked on the pedal principle with the toes, the weaver sitting with his legs in a hole. The combs are supported by ropes attached to beams in the roof, working over pulleys, and stretching down into the well to the toes of the weaver. In his right hand is the shuttle, which contains the thread, and which, passed rapidly through the spaces created by the combs, forms the pattern.

The principal comb is held in the left hand. As the cloth is manufactured, it is wound on the beam by slightly easing the rope on the right hand and turning round the lever. In addition to cotton stuffs used for clothing, the [S. 219] principal fabrics made are tape for bedsteads, carpets or rugs, tent cloth, cordage, &c. Steps have recently been taken to introduce the fly-shuttle ; and six weaving-schools for instruction in its use have been established at Hole-Narsipur, Dod-Ballāpur, Chiknāyakanhalli, Molakālmuru, and other places, with carpentry and drawing classes attached.

Silk fabrics of stout texture and excellent designs are made, chiefly by Patvegars and Khattrīs, in Bangalore and Molakālmuru. Women of the wealthier classes are often richly attired in silk cloths on ceremonial or festival occasions. These, with or without gold and silver or gilt lace borders, are largely manufactured at Bangalore ; the silk and wire used for the purpose are also produced in the State. Sericulture is extensively carried on in the Closepet, Kānkānhalli, Māgadi, Chik-Ballāpur,

Tirumakūdal-Narsipur, and other tāluks ; but Bangalore is the centre of the silk trade, where raw silk is prepared on a considerable scale for the loom and dyed. There has recently been established here, by the late Mr. J. N. Tata of Bombay, an experimental silk farm under Japanese management for improved systems of silkworm rearing, so as to eliminate disease in the worms by microscopic examination of the seed, and for better reeling. Near Yelahanka is also an improved farm belonging to Mr. Partridge for the scientific rearing of silkworms.

The carpets of Bangalore are well-known for their durable quality, and for having the same pattern on both sides. The old patterns are bold in design and colouring. The pile carpets and rugs made in the Central jail from Persian and Turkish designs are probably superior to any other in India. Sir George Birdwood says1 :—

'The stone slab from Koyundjik (palace of Sennacherib), and the door-sill from Khorsabad (palace of Sargon), are palpably copied from carpets, the first of the style of the carpets of Bangalore, and they were probably coloured like carpets.

These South Indian carpets, the Masulipatam, derived from the Abbasi-Persian, and the Bangalore, without any trace of the Saracenic or any other modern influence, are both, relatively to their special applications, the noblest designed of any denomination of carpets now made, while the Bangalore carpets are unapproachable by the commercial carpets of any time and place.'

1 In his splendid book, called The Termless Antiquity, Historical Continuity, and Integral Identity of the Oriental Manufacture of Sumptuary Carpets, prepared for the Austro-Hungarian Government.

Carpets are less used now, and the industry has declined.

Gold circular or crescent-shaped ornaments worn by women on the hair are called rāgate, kyādige, and jede bile. Ornamental silver pins with a bunch of chauri hair for stuffing the chignon or plait are known as chauri kuppe. Ear-rings for the upper rim are named bāvali ; those for the large hole in the lobe, vōle or vāle.

A pear-shaped drop worn on the forehead is called padaka. Necklaces include addike and [S. 220] gundina sara. Bracelets are termed kankani; armlets, vanki, nāga-murige, tohi tāyiti, bandi, and bājuband. A zone is dābu. Anklets of silver are luli, ruli, and kālsarpani; little bells for them, worn by children, are kālu gejje. Silver toe-rings are called pilli.

Silver chains worn by men round the waist are known as udidhāra. The silver shrine containing the lingam worn by Lingāyats is karadige. Small silver money-boxes attached to the girdle are named tāyiti, while an egg-shaped silver chunām box is sunna kāyi.

Iron is widely diffused, and is obtained both from ore and from black iron-sand. The principal places where iron is smelted are in the Māgadi, Chiknāyakanhalli, Malavalli, Heggadadevankote, and Arsikere tāluks, in the southern and central parts of Chitaldroog District, and in the eastern parts of Shimoga and Kadūr Districts. A steam iron foundry has been established at Bangalore under European management.

There are native iron-works at Goribidnūr and Chik-Ballāpur. Sugar-cane mills are made and repaired at Channarāyapatna. The local iron is used for making agricultural tools, ploughshares, tires for cart-wheels, farriery shoes, and so forth. But local manufacture has been driven from the field by the cheaper and better imported articles from

Europe, turned out on a large scale with the aid of machinery. Steel of a very high quality can be made ; but the methods used are primitive, and it cannot therefore compete with the highly finished European products of the present day, though it is preferred by the natives for the edge of cutting tools. Steel is made especially in the Heggadadevankote, Malavalli, and Maddagiri tāluks. Steel wire is drawn at Channapatna for strings of musical instruments, the quality of which makes them sought after throughout Southern India.

The manufacture of brass and copper water and drinking vessels is to a great extent in the hands of the Bhogārs, who are Jains, some of the chief seats of the industry being at Sravana Belgola and Sitakal. Brass is also used for making lamp-stands, musical instruments, and images of the gods ; and bell-metal for the bells and gongs used in temples and in religious services, and by mendicants. Hassan and Tumkūr Districts produce the largest number of these articles.

The potter, as a member of the village corporation, is found in all parts, with his wheel and his mounds of clay.

The principal articles made are pots for drawing or holding water, large urns for storing grain, pipe tiles, and so forth. For sculpture, potstone or soapstone is the common material; and of this superior cooking vessels are made, besides images of the gods, and various ornamental articles. In the higher departments of sculpture, such as statuary and monumental and decorative carving, Mysore holds a high place. The Jain statue of Gomata at Sravana Belgola, 57 feet high, standing on the summit of a hill which rises to 400 feet, is one of the most remarkable works of native [S. 221] art in India.

The decorative sculpture of the Halebīd and Belūr temples Mr. Fergusson considers to be 'the most marvellous exhibitions of human labour to be found even in the patient East,' and such as he believes never was bestowed on any surface of equal extent in any building in the world. The erection of the new palace at Mysore is affording an opportunity of reviving the artistic skill of the sculptors.

Mysore is famous for its ornamental sandal-wood carving. This is done by a class called Gūdigar, who are settled in Shimoga District, chiefly at Sorab. The designs with which they entirely cover the boxes, desks, and other articles made are of an extremely involved and elaborate pattern, consisting for the most part of intricate interlacing foliage and scroll-work, completely enveloping medallions containing the representation of some Hindu deity or subject of mythology, and here and there relieved by the introduction of animal forms.

The details, though in themselves often highly incongruous, are grouped and blended with a skill that seems to be instinctive in the East, and form an exceedingly rich and appropriate ornamentation, decidedly Oriental in style, which leaves not the smallest portion of the surface of the wood untouched.

The material is hard, and the minuteness of the work demands the utmost care and patience. Hence the carving of a desk or cabinet involves a labour of many months, and the artists are said to lose their eyesight at a comparatively early age. A number are being employed on work for the new palace at Mysore.

Many old Hindu houses contain beautiful specimens of ornamental wood-carving in the frames of doors, and in pillars and beams. The art of inlaying ebony and rosewood with ivory, which seems to have been cultivated by the Muhammadans, and of which the doors of the mausoleum at Seringapatam are good examples, has lately been revived at Mysore, and many useful and ornamental articles, such as tables, desks, album covers, &c., are now made there of this work. Similar inlaying is also met with in choice musical instruments, especially the vīna or lute.

Coffee-works at Bangalore, owned by a Madras firm, peel, size, and sort coffee berries in preparation for the European market. During the cleaning season, December to March, about 1,000 hands have been employed, and 1,500 tons of coffee, the produce of Mysore, Coorg, the Nīlgiris, Shevaroys, &c., once passed through the works. The present depression in coffee has reduced these figures to about a fourth. The factory is also engaged in compounding artificial manures for coffee plantations.

There are other similar coffee-works at Hunsūr, as well as saw-mills. A Madras firm has a cotton-ginning factory at Dāvangere. A sugar factory has been established at Goribidnūr, and a brick and tile factory at Bangalore, for machine-made bricks and tiles, fire-bricks, drain pipes, &c. Mention has already been made of the iron foundry at Bangalore, and of the silk farm. [S. 222]

The Mysore Spinning and Manufacturing Company at Bangalore was established in 1883, and is under the management of a Bombay Pārsī firm. The nominal capital is Rs. 4,50,000. The mill contains 187 looms and 15,624 spindles, and employs 600 hands. The Bangalore Woollen, Cotton, and Silk Mills Company at Bangalore was established in 1888, and has a capital of Rs. 4,00,000. It contains 14,160 spindles for cotton, and 26 looms and 780 spindles for woollens. The number of hands employed varies from 500 to 600. In 1903-4 the out-turn was 173,000 lb. of grey goods; 52,000 dozen of other goods; and 1,555.000 lb. of yarn.

Oil-mills are at work in Bangalore. Oil-pressing from the various oilseeds grown in the country is the special calling of the class called Gānigas, who are found in all parts of the State. The number of private native mills was returned as 2,712 in 1904. Concessions for the distillation of the valuable sandal-wood oil are granted by the State.

Tanneries on a considerable scale are managed by Muhammadans in Bangalore, where hides are well cured and prepared for export to European markets.

The only breweries are situated in the Civil and Military Station of Bangalore. Three supply the various beer taverns at Bangalore and the Kolār Gold Fields with what is called 'country beer.' The fourth makes a superior beer for the soldiers' canteens in barracks.

Land management and revenue system

The general system of land tenure is ryotvāri, under which small separate holdings are held direct from government. There is also a certain number of inām tenures, which are wholly or partially revenue free. In 1904 there were 965,440 ryotvāri holdings, with an average area of 7.11 acres, and an average assessment of Rs. 9-6-1. The inām holdings numbered 84,548, with an average area of 20.8 acres, and an average assessment of Rs. 6-5-0. A special class are the leaseholders of gold-mines, whose holdings numbered 44, with an average area in each estate of 912.5 acres, assessed at an average of Rs. 439-6-7.

The sum payable by the cultivator, which is revenue rather than rent, is determined mainly by the class of soil and kind of cultivation. After the revenue survey, the settlement of this point is effected on the following system. Nine classes of soil are recognized, and all the land is divided into 'dry,' 'wet,' and 'garden' land. In the two latter, in addition to soil classification, the water-supply is taken into consideration, and its degree of permanency or otherwise regulates the class to which it is referred.

In the case of gardens irrigated by wells, in addition to the classification of soil, the area of land under each, and the distance of the garden from the village, as affecting the cost of manuring, &c., are carefully ascertained. Villages are grouped according to their respective advantages of climate, markets, communications, and the agricultural skill and actual condition of the cultivators.

The maximum rates for each class of cultivation are then determined by reference to the nature and effects of past management of the tāluk for twenty years, and by examination and comparison of the annual settlements of previous years. These having been fixed, the inferior rates are at once deduced from the relative values laid down in the classification scales.

Of measures intended to improve the position of the cultivators and to relieve them from indebtedness, one of the principal has [S. 215] been the collection of revenue in instalments at such times as enable the cultivator to sell his crop first. There is also the recent Cooperative Societies Regulation.

Taking the natural divisions of east and west, the average rate per acre in the former in 1904 was Rs. 1-7-3, the maximum and minimum being Rs. 2-1-11 and R. 0-10-8; in the latter, the average was Rs. 1-13-1, the maximum and minimum being Rs. 1-14-1 and Rs. 1-12-5. The batai system, or payment of revenue by division of the crop, which formerly prevailed, has been entirely replaced by cash rates.

The daily wages for skilled labour vary in different parts from 6 annas to Rs. 1-8, and for unskilled labour from 2 annas to 8 annas. While the latter has remained at about the same figure as regards the minimum, with a tendency to rise, the former has increased in the last twenty years from 50 to 100 per cent. Payment in kind is becoming less common, probably owing to the influence of railways, mining and other industries, and large public works, the labourer being less tied down to single localities, and having greater facilities to travel at a cheap rate.

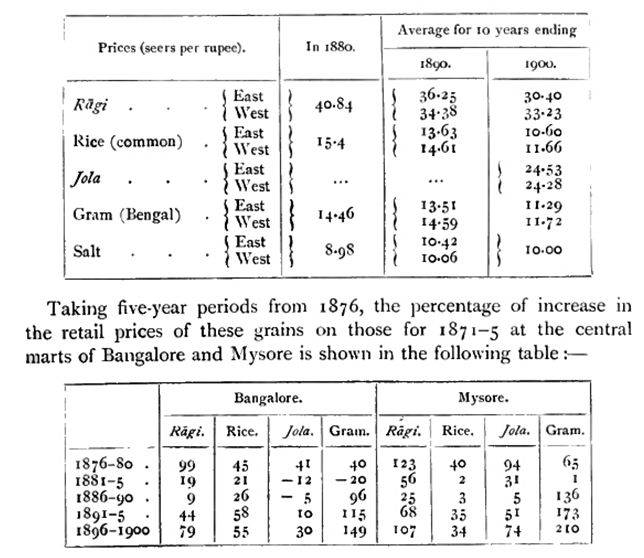

The following table relating to the staple food-grains and salt shows that there has been a general rise in prices, except in the case of salt, which is cheaper :—

The initial increase was due to the famine of 1876-8. A great drop succeeded till 1895, owing at first to good seasons and diminished population, and later to freer means of communication also. In the last period prices have been rising, owing probably both to short crops locally and to the demand from famine-stricken parts elsewhere, especially in Western India.

The general condition of the people has been steadily improving since the middle of the last century, and has made special progress in the past thirty years, as shown by the rise in both wages and prices, and in the standard of living. A moderate assessment has relieved the cultivators, while the easy means of communication provided by roads and railways, together with freer postal facilities, have stimulated the enterprise of traders and benefited all classes.

The prosecution of extensive public works has given labourers and artisans ready employment, and public servants have had exceptional opportunities of rising to good positions. On the other hand, there have been bad seasons in certain years, and in 1876-8 a great famine. Coffee-planting has been almost ruined by the fall in prices.

Cardamoms have suffered from the same cause, and areca-nuts have been injured on a large scale by disease. Plague has also in recent years interfered greatly with the well-being of the people. But education and medical aid are now brought to the doors of all classes, and in important centres the population are better housed, better clothed, and better fed than in the generations past.

The land tenures in the State are sarkār or State, and inām. The former are held under ryotwāri or individual tenure, on payment [S. 232] of kandāyam or a fixed money assessment, settled for thirty years. Kandāyam lands are held direct from the State on annual leases, but the assessment is not as a rule altered or raised during the period for which it is fixed.

The ordinary rates of assessment apply to the whole extent of the ryot's holding, and not to the area actually cultivated, as he has rights to a certain extent over included waste. Remission of assessment is not given in individual cases ; but when there is general loss of crop in a locality and consequent distress, remission may be granted as a measure of relief.

In the case of private estates, such as inām and kāyamgutta villages, and large farms of Government lands cultivated by payakaris or under-tenants, the land is held on the following tenures :

vāram, or equal division of produce between landlord and tenant, the former paying the assessment on the land to the State ;

mukkuppe, under which two-thirds of the produce goes to the cultivator, and one-third to the landlord, who pays the assessment ;

arakandāya or chaturbhāga, under which the landlord gets one-fourth and the cultivator three-fourths of the produce, each paying half the assessment ;

wolakandāya, in which the tenant pays a fixed money-rate to the landlord, which may either be equal to or more than the assessment.

An hereditary right of occupation is attached to all kandāyam lands. As long as the ryot pays the State dues he has no fear of displacement, and virtually possesses an absolute tenant-right as distinct from that of proprietorship. When the State finds it necessary to resume the land for public purposes, he always receives compensation, fixed either by mutual agreement or under the Land Acquisition Act. No legislation has been passed to check the acquisition of land by non-agricultural classes.

In the Malnād or hill country towards the Western Ghāts the holdings of the ryots are called vargs. A varg consists of all the fields held by one vargdār or farmer1 ; and these are seldom located together, but are generally found scattered in different villages, and sometimes in different tāluks. Attached to each varg are tracts of land called hankalu and hādya, for which no separate assessment is paid. Hankalu lands are set apart for grazing purposes, but have sometimes been used for 'dry' cultivation.

Those attached to 'wet' fields are called tattina hankalu. Hādya are lands covered with low brushwood and small trees, which supply firewood or leaves for manuring the fields of the varg. Tracts of forest preserved for the sake of the wild pepper vines, bagni-palms, and certain gum-trees that grow in them, are called kāns, for which a cess is paid. [S. 233]

1 These terms often appear as warg and wargdār in official papers.

Lands for coffee cultivation have been granted from State jungles, chiefly in the Western Ghāts region. The plot applied for was sold by public auction. If the jungle was to be cleared, notice was given, to allow of officials removing or disposing of 'reserved' trees. Besides coffee nothing may be grown on the land, except shade trees for the coffee. Within five years a minimum of 500 coffee-trees to the acre must be planted.

On the coffee-trees coming into bearing an excise duty, called hālat, of 4 annas per maund, was formerly levied on the produce, in lieu of land rent. But from 1885 an acreage assessment was substituted—either R. 1 per acre, with a guarantee for thirty years on the terms of the survey settlement, or a permanent assessment of Rs. 1½ per acre, on the terms of the Madras Coffee Land rules. Nearly all the large planters have adopted the latter conditions. But the great fall in the prices of coffee in recent years, owing to the competition of Brazil, has reduced this previously flourishing industry to a very depressed condition.

Lands have been offered since 1904 for rubber cultivation, in plots of 50 acres, selected with the consent of the Forest department, to be held free of assessment for the first five years, and subject to the assessment fixed by the survey settlement in the sixth year and after. The work of planting must be commenced within one year from the date of the grant ; and in stocking the area with rubber plants, trees may not be felled without permission.

Lands for cardamom cultivation are granted from the jungles on the eastern slopes of the Western Ghāts, where the plant grows wild. Tracts of not less than 5 or more than 200 acres, when applied for, are put up to auction, and may be secured on a twenty years' lease on terms similar to those for coffee lands. Not less than 500 cardamom plants per acre must be planted within five years, and nothing else may be cultivated on the ground. Trees, except of the 'reserved' kinds, may be felled to promote the growth of the cardamoms.

The tenure called kāyamgutta literally means a 'permanent village settlement' It owes its origin probably to depopulated villages being rented out by the State on a fixed but very moderate lease, on the understanding that the renter would restore them to a prosperous condition. But in the early part of last century even flourishing villages were granted to court favourites on this tenure, and some of the most valuable lands are thus held. Shrāya lands are waste or jungle tracts granted at a progressive rent, in order to bring them under cultivation.

They are free of assessment for the first year, and the demand increases afterwards yearly from one-quarter to full rates in the fourth or fifth year. For the planting of timber, fruit, and fuel trees, unassessed waste land, or assessed 'dry' land, if unoccupied for ten years consecutively, [S. 234] is granted free of assessment for eight years, then rising by a quarter rate to full assessment in the twelfth year.

The conditions on which inām tenures are held vary considerably. Some are free of all demands, while in others the usual assessment is reduced. The grants differ also in origin, according as they were made to Brāhmans, for religious and charitable purposes, to village servants, for the maintenance or construction of tanks and wells, or otherwise.

Licences for exploring for minerals, on areas approved by Government, are granted on deposit of a fee of Rs. 10, to run for one year. No private or occupied lands may be explored without the consent of the owner, occupier, or possessor. Prospecting licences for minerals may be obtained for one year, on a minimum deposit of Rs. 100, and a rent of Rs. 50 per square mile or portion of a square mile. The licensee may select, within the year, a block for mining, not exceeding one square mile, in the licensed area.

Mining leases limited to one square mile, of rectangular shape, are granted for thirty years, on deposit of Rs. 1,000 as security, and furnishing satisfactory evidence that a sum of £10,000 will be raised within two years for carrying on mining operations on the block of land applied for.

The cost of survey and demarcation is paid by the applicant, and mining operations must start within one year. An annual rent of R. 1 per acre is payable to the State on the mining block, together with all local cesses and taxes ; and in each year in which a net profit is made, a royalty of 5 per cent. is levied on the gross value of gold and silver produced. If the net profits exceed £25,000, an additional royalty is payable of 5 per cent. on the net profits above that sum. But in the case of a registered company, the royalty may be paid on divisible instead of net profits.

The land revenue assessment is fixed by the Revenue Survey department on the method already described (p. 214, above). The system resembles that followed in Bombay, which was preferred to that of Madras. The former was chosen because all the steps in survey, classification, and settlement are under the direction of one responsible head, and made to fit into one another.

The present revenue survey was introduced in 1863, and the settlement was completed in 1901. The settlements made under it are current for thirty years. The previous survey, made at the beginning of the nineteenth century, was necessarily very imperfect; and after the lapse of fifty years the records had become extremely defective, advantage having been taken of the insurrection in 1830 to destroy the survey papers in many cases.

In 1700 the Mysore king Chikka Deva Rājā acknowledged one-sixth to be the lawful share of the crop to be paid to him, but added [S. 235] a number of vexatious petty taxes to enhance the amount indirectly. In Bednūr (Shimoga District) Sivappa Naik's shist, fixed in 1660, was one-third of the gross produce.

This continued for thirty-nine years, after which various additions were made, chiefly to raise funds for buying off the enemy. After the overthrow of Tipū Sultān, during the eleven years of Pūrnaiya's administration (1800-10), the highest land revenue was equivalent to 94 lakhs in 1809, and the average was 83 lakhs. During the twenty-one years of the Rājā's administration which followed (1811-31), the highest was 90 lakhs, and the average 79 lakhs.

In the first year of British administration (1831-2), the land revenue was set down as 48 lakhs, but included in this were 83 different cesses, besides 198 taxes unconnected with it. The general average assessment was usually one-third of the gross produce. In 1881-2 the total revenue was 107 lakhs, of which the land yielded 71 lakhs. In 1903-4 the total revenue had risen to 214 lakhs, and the land revenue to 98 lakhs.

Minerals

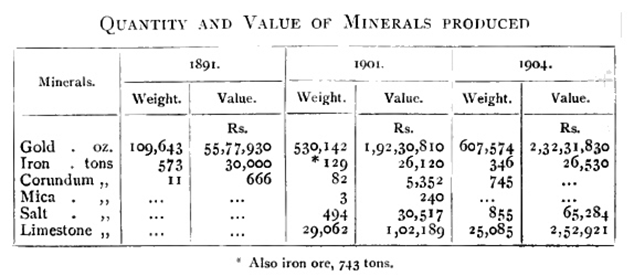

Gold is the only mineral raised from mines. These were being worked by thirteen companies in 1904, of which five paid dividends, [S. 218] three produced gold but paid no dividend, and the rest were non-producers. All but three, which are included in the non-producing class, belong to the Kolār Gold Fields.

The ore is treated by milling and amalgamation, and the tailings by cyanide. Steam power has been replaced since June, 1902, by electric power, generated at the Cauvery Falls, 92 miles distant. The number of persons employed in the industry in 1903 was 27,355. Of these, 76 per cent. were Hindus, 18 per cent. Christians, and 6 per cent. Muhammadans.

The great majority of the Hindus were Holeyas, the others being mostly Wokkaligas, Tigalas, and Woddas. The Christians consisted of 17 per cent. Europeans, 22 per cent. Eurasians, and 61 per cent. natives. The amount paid in wages was 70.3 lakhs, which gives an average earning of Rs. 257 per head per annum. The five dividend-paying companies are the Mysore, Champion Reef, Ooregum, Nundydroog, and Bālāghāt.

The nominal capital of all the companies was £2,958,500, and the paid-up capital £2,683,000. All the gold produced is dispatched to England. Minerals as yet unworked in the State include a small quantity of asbestos. Iron is smelted in several places. Some manganese has lately been exported from Shimoga District.

Occupations

The occupations of the people have been returned under eight main classes. Of these the most important are : pasture and agriculture, which support 68 per cent. of the population ; preparation and supply of material substances, 11 per cent. ; and unskilled labour not agricultural, 9 per cent. Actual workers number 1,875,371 (males 1,485,313, females 390,058), and dependents number 3,664,028 (males 1,311,711, females 2,352,317).

Railways

The system of railways radiates from Bangalore, and there is no District without a railway running through some part of it. The Bangalore branch of the Madras Railway, standard gauge, runs for 55½ miles in the State, east from Bangalore city to Bowringpet, then south-east to the main line at Jalārpet. From Bowringpet the Kolār Gold Fields branch, 10 miles in length, on the same gauge, runs first east and then south to the end of the Mysore Minefield.

The Southern Mahratta Railway, metre gauge, runs southwest through Mysore to Nanjangūd, and north-west through Harihar [S. 224] towards Poona, for 312 miles in the State. From Yesvantpur a branch, 51 miles in the State, runs north through Hindupur to Guntakal on the Madras Railway.

From Birūr a branch, 38 miles long, runs north-west to Shimoga. Surveys have been made to extend the line from Nanjangūd south-east to Erode on the Madras Railway, and also for a 2½ feet gauge line to the west coast, either from Arsikere to Mangalore, 86 miles in the State, or from Mysore to Tellicherry, 58 miles in the State.

The Southern Mahratta Railway Company has proposed a metre-gauge line from Mārikuppam in Kolār District to Dodbele station in Bangalore District, in order to provide direct communication between the Gold Fields and the port of Marmagao ; and the survey for it is being made. A light railway on the 2½ feet gauge, from Bangalore north to Chik-Ballāpur, 36 miles, is projected by a private company.

The total length of line open in 1891 was 367 miles, of which 55½ were standard gauge, and the rest metre gauge. In 1904 the total was 466½ miles, the addition being all metre gauge. The Kolār Gold Fields branch is worked by the Madras Railway; the remaining Mysore State lines by the Southern Mahratta Railway on short-term agreements. For the Mysore-Harihar line the Southern Mahratta Railway Company raised a loan on a guarantee of 4 per cent. interest by the Mysore State, which also pays to the company one-fourth of the surplus profits.

The capital outlay on all the lines owned by the Mysore State up to 1904 is 2.3 crores, of which 1.6 crores was incurred on the Mysore-Harihar line. The number of passengers carried in 1903-4 was 2½ millions. The total expenditure was 7.7 lakhs, and the net earnings 7 lakhs. The Kolār Gold Fields and the Bangalore-Hindupur lines were the only two that showed a surplus, after deducting 4 per cent. for interest on the capital outlay.

The railways were expressly designed to serve as a protection against times of scarcity; and since the great famine of 1876-8, when the only railway was the Bangalore branch of the Madras Railway as far as the cantonment, the pressure of severe distress has been averted. Prices have no doubt tended to become equalized. It is not known that any change in the language or customs of the people has arisen from the extension of railways.

Roads and highways

Trunk roads run through all the District head-quarters to the frontiers of the State, connecting the east coast and adjoining British Districts by way of the Mysore table-land with the west coast. In 1856 there were 1,597 miles of road in the State. Besides the construction of new roads, improvements in the alignment of old ones, provision of bridges across rivers, and other measures to ensure free transit have since been continuously carried out. A good system of local roads radiates from each District head-quarters to all parts of the [S. 225] District.

The previously almost inaccessible Malnād tracts in the west were the last to benefit, but these were generally opened up by about 1870. Much attention has also been paid to improving the ghāt roads through the passes in the mountains to the west. As railways have extended, feeder roads have been made in those parts where none existed.

The old style of carts had a solid wooden wheel. They are known as Wodda carts, and are still employed at quarries for the transport of stone. But for general purposes they have long been superseded by carts with spoked wheels, but without springs. These take a load of over half a ton, and are drawn by a pair of bullocks. In the western parts a broad wain, drawn by several pairs of bullocks, is used for harvesting purposes.

In 1891 there were 1,730 miles of Provincial roads and 3,113 miles of District or Local fund roads. In 1904 the figures were 1,927 miles of Provincial roads, costing for upkeep an average of Rs. 199 per mile ; and 3,502 miles of District or Local fund roads, maintained at an average cost of Rs. 72½ per mile.

A steam tramway is proposed for 18 miles from Shimoga for the transport of the manganese ores that are being collected there.

Owing to either rocky or shallow beds, none of the Mysore rivers is navigable, nor are there any other waterways for such use.

Trade and exports

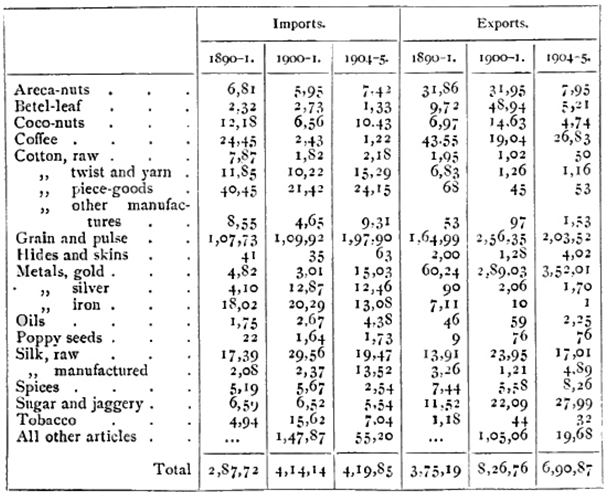

The extension of railways and the opening out of roads have greatly increased the facilities for trade. So far as the figures can be relied on, the value of exports is about double that of imports. The most valuable imports are grain and pulse, articles of iron and steel, raw silk, piece-goods, tobacco, and cotton thread.

The chief exports, next to gold, are grain and pulse, betel-leaf, areca-nuts, raw silk, sugar and jaggery, coffee, and coco-nuts, chiefly the dried kernels. Among imports, tobacco trebled during the ten years ending 1901. Among exports, while gold increased nearly 100 per cent., coffee fell 44 per cent. The export of sugar and jaggery and of coco-nuts (dry and fresh) doubled, while that of betel-leaf quadrupled.

The principal Hindu trading classes of the country are Banajigas, Komatis, and Nagartas ; after whom come the Tamil Mudalyārs and Musalmāns. The traffic in grain is not entirely in the hands of traders, for the ryots themselves are in the habit of clubbing together and sending off one or two of their number to deal in grain at any convenient market or fair.

Apart from the railway, the common mode of carriage and transport is by country carts, the ordinary load of which exceeds half a ton, drawn by bullocks which go 18 to 20 miles a day. But in remote forest tracts and the hills, droves of pack-bullocks and asses are still used, the carriers being generally Lambānis or Korachas. [S. 223]

Trade outside the State, excepting for gold and coffee, which are sent to England, is chiefly confined to the surrounding British Districts. Gold goes via Bombay, coffee generally by way of Mangalore or Marmagao, the producers in both cases being, with hardly an exception, Europeans. The principal trading centres in the State are noted under their respective Districts. A Bangalore Trades Association has been formed, chiefly among the European shopkeepers in the Civil and Military Station.

The following table gives statistics of the total value (in thousands of rupees) of imports and exports. The total value of the rail-borne trade alone is given as—in 1890-1, imports 2.5 crores, exports 2.8 crores ; in 1900-1, imports 3.8 crores, exports 3.4 crores. Details are not available.