Muhammad Ali Jinnah

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A lean phase

The Times of India, Jun 28 2015

Excerpted from `Midnight's Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India's Partition and Asia' with permission from Penguin India

Before he rose to forge Pakistan, the Muslim League leader suffered a humiliating fall from grace, writes Nisid Hajari in a new book

In the summer of 1916, the man who would go on to found Pakistan, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, ran up against one of India's most stubborn communal prejudices. His good friend Sir Dinshaw Petit had invited him to escape Bombay's suffocating heat and spend several weeks in cool Darjeeling. Sir Dinshaw was a Parsi, and heir to a textile fortune. More importantly , he had a 16-year-old daughter -a sinuous beauty named Rattanbai, or “Ruttie.“ Jinnah would have been hardpressed to ignore her presence. She wore gossamer-thin saris that clung to her body and had a ready , flirtatious laugh. One prim memsahib described her as “a complete minx.“

Ruttie

Like many Indians, Jinnah had been married young to someone of his parents' choosing, a 14-year-old Gujarati village girl named Emibai. A year later she had died while he was away studying in London. He told friends that he hadn't kissed a woman since then (although, hearing that particular tale, the irrepressible poetess Sarojini Naidu trilled, “Liar, liar, liar!“). Jinnah left no record of what transpired between him and Ruttie amid the emerald tea plantations of Darjeeling, but clearly a romance blossomed.

When they returned to Bombay at the end of the summer, Jinnah asked Sir Dinshaw how he felt about intermarriage.The Parsi didn't realize what his Muslim friend was angling at. A capital idea, Petit declared -just the thing to help break down the foolish barriers that divided Indians from one another. Jinnah's next question horrified him, though. The nearly 40-year-old Muslim marrying his teenage daughter? The idea was “absurd!“ Sir Dinshaw not only refused but took out a restraining order against Jinnah.

Jinnah was not to be discouraged, however, either personally or politically .He and Ruttie continued to correspond secretly . Like many of the youth in her circle she was enthralled by the romance of the nationalist movement, and that winter she eagerly followed the news coming out of the graceful Mughal city of Lucknow, capital of the United Provinces, where Jinnah had helped arrange for the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress to hold their annual sessions simultaneously. For the first time the two parties agreed on a common set of demands to make of the British -what became known as the “Lucknow Pact.“ Jinnah won for Muslims a guaranteed percentage of seats in any future legislature, among other safeguards that would ensure they were not perpetually outvoted by the Hindu majority .

The Lucknow Pact raised Jinnah's political stock sky-high; he seemed a shoo-in to become president not just of the League, but perhaps even the much larger Congress one day . A few months later, soon after Ruttie had turned 18, she and Jinnah scandalized Bombay's Parsi community by eloping. They quickly became one of the city's most glamorous couples, cruising down Marine Drive in Jinnah's convertible at sunset each night, her hair loose in the wind.

Then Jinnah threw it all away . Just as his political career was reaching its zenith, the spotlight shifted to another Gujarati lawyer, born just 30 miles from Jinnah's ancestral village. In 1915 a 45-yearold Mahatma Gandhi had returned to India from South Africa, where he had lived for the past two decades, and where his efforts to organize South Africa's Indian immigrant community had made him a celebrity .

Gandhi dubbed his strategy satyag raha -literally , “soul force“ -and he now proposed replicating his methods in India. Jinnah balked. He did not challenge the principle behind satyagraha -the idea that Indians should peacefully refuse to cooperate with their British overlords.“I say I am fully convinced of non-cooper ation,“ Jinnah declared at a contentious Congress meeting in September 1920. But he did not believe that the Indian masses were educated or disciplined enough to ensure their protests remained nonviolent. He thought Congress leaders needed to prepare their followers first. “Will you not give me time for this?“ he asked the crowd at the meeting, plaintively .

Not all of Jinnah's motivations were so high-minded, of course. He was unquestionably a snob: later, when tens of thousands of Muslims turned out at ral lies to see him, he would recoil from shaking hands with his own supporters. He also found Gandhi's appeal to the largely Hindu masses dangerously crude. At his evening prayer meetings, the Mahatma would frame his political arguments using parables from Hindu fables; he described his vision for independent India as a “Ram Rajya“ -a mythical state of ideal government under the god Ram. All the chanting and meditating that accompanied Gandhi's sermons seemed to Jinnah like theatrics.

What is almost never acknowledged, though, is that Jinnah worried less about Hindus than about the danger of inflaming religious passions among Muslims.At the time mullahs across the subcontinent were threatening to launch a jihad if the British, who had defeated the Ottomans in World War I, deposed the Turkish Sultan -the caliph, or leader, of the world's Sunnis. Led by a pair of fiery brothers, Mohammed and Shaukat Ali, this “Khilafat“ movement had attracted an unsavory mob of supporters. The acerbic Bengali writer Nirad C. Chaudhuri remembers Khilafat volunteers as “recruited from the lowest Muslim riffraff...brandishing their whips at people.“

Jinnah had no sympathy for these rough-edged Muslims, or for their fanatic cause. He feared that their rage would inevitably turn from the British to Hindus. Gandhi, on the other hand, threw his support behind the Khilafat movement: in turn Muslim votes gave him the slight majority in Congress he needed to launch his satyagraha. Years later Gandhi recalled Jinnah telling him that he had “ruined politics in India by dragging up a lot of unwholesome elements in Indian life and giving them political prominence, that it was a crime to mix up politics and religion the way he had done.“

Nowadays most Indian accounts put down Jinnah's opposition to Gandhi to jealousy . At a follow-up Congress meeting in December 1920, they often note, Jinnah drew jeers by referring to “Mister“ Gandhi in his speech, rather than the more respectful “Mahatma.“ In fact, although he did slip once or twice more, Jinnah did switch to using “Mahatma.“ What he absolutely refused to do was refer to Khilafat leader Mohammed Ali as “Maulana,“ a term reserved for distinguished Islamic scholars. Jinnah was not about to encourage what he saw as religious demagoguery . “If you will not allow me the liberty to ... speak of a man in the language which I think is right, I say you are denying me the liberty which you are asking for,“ he vainly protested. The crowd's howls chased him off the stage.

The humiliating scene marked the beginning of Jinnah's long slide into irrelevance as a national political figure.Under Gandhi's influence a new, less august crowd dominated Congress meetings -middle-class and lower-middle-class men and women, clad in saris and kurtas and sitting on the ground cross-legged rather than in chairs. Jinnah still got upset when his bearer laid out the wrong cufflinks for him. He no longer fit in.

Jinnah did not disappear from the political scene, but as Gandhi's Congress grew larger and larger, the League leader was pushed further and further to the margins. He became what he had never wanted to be -a purely Muslim politician, reduced to petitioning for concessions for his community . By the end of the 1920s, the League had begun to break up into factions, and Jinnah's influence had become negligible.

This was not the illustrious nationalist hero with whom the impressionable Ruttie had fallen in love. After giving birth to a daughter, Dina, in August 1919, Ruttie had plunged into a half-baked mysticism, taking up crystals and seances. She may have begun using drugs like opium to combat a painful intestinal ailment. The differences in the couple's ages and temperaments became too obvious to ignore.“She drove me mad,“ Jinnah told one friend. “She was a child and I should never have married her.“ In early 1928, Ruttie moved into a suite at Bombay's Taj Mahal Hotel, leaving Jinnah home with eight-year-old Dina. That spring, visiting Paris with her mother, Ruttie fell into an unexplained coma and almost died.

While she recovered, their relationship did not. Two months later, on February 19, 1929, Ruttie fell unconscious in her room at the Taj Hotel. She died the next day , on her 29th birthday .

Most accounts say only that the circumstances of Ruttie's demise were “mysterious.“ But her daughter Dina put it more bluntly: “My mother committed suicide,“ she told Jinnah's first biographer. The embarrassed author left that nugget out of his hagiography . Still, even at the time rumors about the death were rife. Jinnah never wanted to be reminded of his private tragedy , which had become so humiliatingly public. He packed away Ruttie's jades and silks and volumes of Oscar Wilde in boxes and rarely mentioned her again.

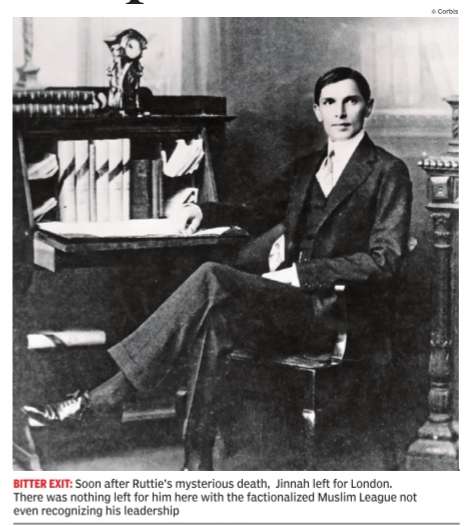

There was nothing left for Jinnah in India. In its two decades of existence, the Muslim League had accumulated fewer than 2,000 members, most of whom did not pay their dues. Creditors tried to seize what little furniture remained at League headquarters to sell at auction. Parts of the factionalized party did not even recognize Jinnah's leadership.

In 1931 Jinnah moved to London with Dina and his spinster sister Fatima. He refused to answer questions about when-or if--he would return to India. “I seem,“ he told an Indian journalist over lunch at Simpson's, with startling candor, “to have reached a dead end.“

In Indian political discourse

As in 2022

Adrija Roychowdhury, February 3, 2022: The Indian Express

Jinnah has surfaced in Indian political discourse several times in the past, especially at the time of elections. To the votaries of Hindutva, Jinnah has always stood as the man who must be blamed for the partition of the country along communal lines 75 years ago.

In their speeches, BJP leaders have often attacked their political opponents calling them “supporters” of Jinnah. Last year, BJP national president J P Nadda accused Samajwadi Party leader Akhilesh Yadav of preferring Jinnah over Patel, the nation’s first home minister and the leader who is credited with uniting India politically after independence.

While the references to “Jinnah” have often been used as political code for alleged “Muslim appeasement” by the BJP’s opponents and a dog whistle for polarisation along communal lines, the founder of Pakistan who died in 1948 has also caused controversy within the BJP, and led to setbacks for leaders such as former Deputy Prime Minister L K Advani.

L K Advani (2005)

In June 2005, Advani paid an emotional visit to Karachi, his place of birth in undivided India. At Jinnah’s mausoleum in the city, Advani, who was then 78, praised the founder of Pakistan, calling him a “great man”.

Advani’s visit to the mausoleum was the most high-profile by an Indian leader until then, and given his position as Deputy Prime Minister until just a year ago and the man who made the biggest contribution to the BJP’s adoption of Hindutva as its political identity, it was covered extensively in the media.

Advani wrote in the register at the mausoleum: “There are many people who leave an inerasable stamp on history, but there are very few who actually create history. Quaid-e-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah was one such rare individual.

“In his early years, Sarojini Naidu, a leading luminary of India’s freedom struggle, described Mr Jinnah as an ‘ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’. His address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on August 11, 1947, is really a classic, a forceful espousal of a secular state in which, while every citizen would be free to practise his own religion, the state shall make no distinction between one citizen and another on grounds of faith. My respectful homage to this great man,” added Advani.

Advani’s warm comments on Jinnah were ironic given that in 1947, he had been named as an accused in a murder conspiracy case against Jinnah. News reports of the time recorded that throughout his visit in Pakistan, Advani was asked to comment on the case, which he laughed away.

But his comments came as a rude shock to the BJP, which was still to recover from the unexpected defeat in the Lok Sabha elections of 2004. The R S S was explicit in disagreeing with Advani’s praise of Jinnah.

While Advani refused to withdraw his statements, he offered to resign as party president after his return to India. However, he withdrew his resignation a few days later, even though his relationship with the R S S remained strained.

Less than seven months after he withdrew his resignation though, Advani stepped down from the post, and Rajnath Singh became BJP president.

Jaswant Singh (2009)

Jinnah became a point of controversy for the saffron party once again in 2009 after Jaswant Singh’s book, ‘Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence’, appeared. Singh had been a very important member of Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s government, and earlier served as India’s minister for finance, external affairs, and defence.

Jaswant Singh provided an alternative reading of the Quaid-e-Azam, which was different from the mainstream political narrative in India. He mentioned Jinnah as being as “ambassador for Hindu-Muslim unity”, even though, like Advani, he cited someone else for this description.

Jaswant also presented Jinnah as more of a pragmatic politician than a religious radical. In a television interview given before the book’s release, he claimed that “Jinnah was demonized by India while it was actually India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s belief in a centralized polity that led to partition.”

Soon after the book was released, Singh was expelled from the BJP. The party president at the time, Rajnath Singh, stated that “the party fully dissociates itself from the contents of the book”.

The R S S had already distanced itself from the book even before its release. There were incidents of some Hindu radicals burning copies of the book, and it was banned in Gujarat, where Narendra Modi was Chief Minister at the time.

Aligarh Muslim University (2018)

In May 2018, the BJP MP from Aligarh, Satish Gautam, wrote a letter to AMU Vice-Chancellor Tariq Mansoor objecting to the display of Jinnah’s portrait in the university’s student union office. Violence broke out on campus as students objected to the protests held by the right wing group Hindu Yuva Vahini demanding the removal of Jinnah’s portrait.

Later, AMU spokesperson Shafey Kidwai said the portrait had been hanging in the university’s students’ union office for decades. Jinnah, he noted, was a founding member of the university court, and was granted lifetime membership of the student union. As per the university’s tradition, portraits of all lifetime members are placed on the walls of the student union office by rotation.

“He was granted membership before the demand of Pakistan had been raised by the Muslim League,” Kidwai said, adding that no national leader had raised an objection to his portrait in the university including Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Dr Rajendra Prasad.

The controversy over Jinnah’s portrait resurfaced in the run-up to the Bihar Assembly elections of 2020. The BJP attacked the Congress for fielding former AMU student Maskoor Usmani as its candidate from Jale in Madhubani, calling the latter a “Jinnah supporter”.

“Congress and Mahagathbandhan have to clarify if they too support Jinnah,” BJP leader and Union minister Giriraj Singh had said. The Congress defended Usmani’s candidature, stating that he had nothing to do with Jinnah’s ideology.

Akhilesh Yadav (2021)

In October 2021, Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh Yadav triggered controversy after he took Jinnah’s name in the same breath as that of Patel, Gandhi, and Nehru as fighters for India’s independence.

“Sardar Patel, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and (Muhammad Ali) Jinnah studied in the same institute. They became barristers and fought for India’s freedom,” Akhilesh said at a public rally in UP’s Hardoi.

The BJP was quick to attack Akhilesh. “The Samajwadi Party chief yesterday compared Jinnah to Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. This is shameful. It’s the Talibani mentality that believes in dividing. Sardar Patel united the country,” said Chief Minister Adityanath, according to news agency ANI.

BJP spokesperson Rakesh Tripathi said: “The country considers Muhammad Ali Jinnah as the villain of the partition. Calling Jinnah the hero of freedom is the politics of Muslim appeasement.”

Reacting to the criticisms from the BJP, Akhilesh advised his detractors to read the history books on Jinnah again.

Patriotism towards India

When Jinnah agreed to a united India

Saurabh Banerjee, August 22, 2021: The Times of India

As tributes go, Stanley Wolpert’s praise for Mohammad Ali Jinnah was gushing. ‘Few individuals,’ wrote Wolpert in his biography of Jinnah, ‘significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three.’ Except, in June 1946, Jinnah agreed to a plan which would neither have modified the map, nor created a nation-state.

The Muslim League had largely been an elitist party but all that changed in 1940. The other change that year was Jinnah’s increasingly shrill pitch for the creation of Pakistan. On March 25, 1940, at the end of the Lahore session of the League, Jinnah gave a press conference. ‘The declaration of our goal,’ he said, ‘which we have definitely laid down, of the division of India, is in my opinion a landmark in the future history of the Mussalmans of India…. I thoroughly believe that the idea of one united India is a dream.’

Later that year, he told the Delhi Muslim Students’ Federation: ‘The Hindus must give up their dream of a Hindu raj and agree to divide India into Hindu homeland and Muslim homeland. Today we are prepared to take only one-fourth of India and leave three-fourth to them. Pakistan was our goal today, for which the Muslims of India will live for and if necessary die for. It is not a counter for bargaining.’

But in 1946, the same Jinnah was willing to accept a united India — minus Pakistan. How did that happen?

The War had ended. The last great imperialist, Winston Churchill, had been swept out of office in a Labour landslide. It was clear that Britain would have to leave India. So, Clement Attlee, then the British PM, cleared a three-member Cabinet Mission to visit India and try and hammer out a solution. Maybe it was already too late, but this would be the last attempt at an orderly withdrawal. Secretary of State for India, Lord Freddie Pethick-Lawrence, was the nominal head of this mission. But the heavyweight was Sir Stafford Cripps, whose earlier mission to find a solution in 1942 had come to nothing. This time round Cripps was determined to go down in history as the person who had finally found the Answer to the ‘India Question’. To balance out these two public-school socialists, Attlee picked as the third member, the First Lord of the Admiralty, AV Alexander, a working-class Labour leader and a Chelsea supporter who loved beer and poetry.

The mission left Britain on March 19, 1946. This would be Cripps’ third visit to India. For Pethick-Lawrence, it would be the second. For years, he had written a weekly column for Annie Beasant’s ‘New India’. His wife, a suffragette, was a member of the India Conciliation Group, set up on Gandhi’s advice after the Second Round Table Conference. Cripps’ stepmother, too, was a member of this group. To the optimist, it might have seemed a solution was in the offing.

For Britain one thing was very clear. India should remain united. Because to divide India would be to divide its armed forces. How would one do that, without a very weak Pakistani army which would not be able to defend its western frontier?

By April 10, the mission had drawn up its plans. There would be two schemes. Scheme B would be the choice of the last resort, if there was absolutely no way of getting Indian players to accept Scheme A.

Broadly, Scheme A was a plan for a loose federation of Hindu-majority, Muslim-majority and princely states. It would be a three-tier system of government. At the top would be a small central ‘union’ government, which would look after communications, defence and foreign affairs. There would be equal representation of Hindus and Muslims at the centre. At the bottom would be the individual provinces. In the middle would be a grouping of provinces with a large degree of autonomy and power to secede from the union in the future. One group was to comprise Sindh, Punjab, Balochistan and the North-West Frontier Province. Another, Bengal and Assam. And the third was the rest of India. Scheme B was to divide India into ‘Hindustan’ and a truncated Pakistan, a plan which Britain wanted to avoid at all cost.

The mission spent about three and a half months in India. Pethick-Lawrence managed to faint in the summer heat when the mercury touched 46 degrees Celsius, and then apologised for his ‘terrible weakness’. Cripps came down with colitis and spent some days in hospital. Alexander struck up a friendship with viceroy and governor general, the one-eyed Archibald Wavell, and bonded over poetry and piano. Hectic meetings took place in the summer heat and Wavell suspected Pethick-Lawrence and Cripps were being soft on Congress. In fact, he was appalled when Gandhi asked for water during a meeting, Pethick-Lawrence himself got up to fetch water, and when he was taking some time to return, Cripps went out to get water for Gandhi.

And then in May, they all escaped to Simla where Cripps, Pethick-Lawrence, Alexander and Wavell met the Indian politicians separately in batches. Gandhi, too, reached Simla in a special train. The stage was set for hard negotiations.

But there was far too much animosity between the League and the Congress. At the opening session, Jinnah refused to shake hands with Abdul Kalam Azad, calling him a ‘stooge’ of the Hindus. By May 12, Pethick-Lawrence declared the Simla session closed. Little progress had been made.

But the mission issued a statement. They declared the creation of a constituent assembly of elected representatives from 11 provinces who would frame a new constitution. They also outlined Scheme A, which explicitly opposed the creation of Pakistan, and made it clear that Pakistan, if created, would be a truncated version of Punjab and Bengal. The ball was now in the court of Jinnah and Congress.

On June 6, 1946, Jinnah agreed to Scheme A. This was his best bet, even though it would lead to speculation that Pakistan had, after all, been a bargaining chip for him, never mind what he had told students in November 1940. While this would not give him Pakistan now, it would not leave him with a ‘moth-eaten’ state to inherit. Besides, there was always the provision to leave the union in the future. He couldn’t have known that he would be dead in two years’ time.

Initially, Gandhi seemed willing to go along with this scheme. It would, he said, ‘convert this land of sorrow into one without sorrow and suffering’. But then Congress changed tack and refused to play ball. What did it have to lose? Jinnah could get his truncated lands, and India would be a strong, united country, with a powerful Centre, have its own constitution, its own secular philosophy. After that both sides hardened their stance. On August 16, Jinnah gave his call for Direct Action. One riot led to another, and then by mid-August 1947, two countries were born.

Wolpert’s superman, MA Jinnah, a Khoja Shia by birth, a London lawyer in Saville Row suits puffing away at his Craven A cigarettes, a man who had seduced the young daughter of his Parsi businessman friend and then married her, a man who built his politics around Islam but loved his ham sandwiches, a man who once talked of Hindu-Muslim unity, thus ended up being the father of a Sunni nation-state.

Sources: Jinnah: His Successes, Failures And Role In History by Ishtiaq Ahmed, Keeping The Jewel In The Crown by Walter Reid, Liberty Or Death by Patrick French

Saurabh Banerjee is Associate Editor, The Times of India.

Sudheendra Kulkarni’s argument

Sudheendra Kulkarni, Nov 2, 2021: The Times of India

Nearly 75 years after India’s Partition, Mohammed Ali Jinnah (1876-1948), the architect of Pakistan, never seems to fade away from our country’s political discourse. Was he one of the nayaks (leaders) of India’s freedom struggle or only its khalnayak (villain)? Or was he both?

There is no place for the first or the third answer in today’s highly polarised social and political atmosphere, where Muslims and Pakistanis have been made the ‘other’. With nuance and uncomfortable facts having been banished from the reading of history, any contention that Jinnah was once an ardent Indian patriot invites the charge of being a ‘deshdrohi’ (anti-national).

Even LK Advani, the second-tallest leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party in the pre-Modi era, had to pay a heavy price for speaking the truth. During his visit to Pakistan in 2005, Advani went to Jinnah’s mausoleum in Karachi and wrote the following words in the visitor’s book: “There are many people who leave an irreversible stamp on history. But there are few who actually create history. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah was one such rare individual.”

Sarojini Naidu, a leading luminary of the freedom struggle, described Jinnah as an ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity. His address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on August 11, 1947 is really a classic and a forceful espousal of a secular state in which every citizen would be free to follow his own religion. The State shall make no distinction between the citizens on the grounds of faith. My respectful homage to this great man."

Every word in this tribute is factually true. Yet, Advani was forced by his own party and ideological parivar to resign as president of the BJP.

Now, it is the turn of Akhilesh Yadav, president of the Samajwadi Party, to be pilloried for a remark he made on Jinnah on Sunday. At his party’s rally in Uttar Pradesh, he said, “Sardar Patel, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Jinnah studied at the same institute and became barristers. They fought for India's freedom.”

He is factually correct. But, in BJP’s historiography, it is unacceptable. BJP leaders have slammed him as “Akhilesh Ali Jinnah” for “eulogising a person who divided India”. Some even accused the SP chief of having a “Talibani mindset”!

But let’s examine the main points about the history of Partition.

Was India’s Partition a monumental tragedy? Indeed, it was. Was Jinnah culpable for it? Of course, he was. He bears principal responsibility for it, although many other personalities, parties and factors also contributed to India’s division at the very moment when it gained freedom from British rule. However, to attribute this complex historical development to the “evil designs” of one individual — and that too for the purpose of communal polarisation of a state heading to a crucial assembly election — is a vile attempt at falsification of history.

Jinnah is one of the most misunderstood leaders of India’s freedom struggle. This is true in both India and Pakistan — and for opposite reasons. Most Hindus in India regard him as the villain who was responsible for India’s division.

What they disregard, as much out of ignorance as out of prejudice, is that Jinnah tried his utmost to prevent Partition. While strenuously fighting for Muslim rights, and for a fair and honourable share of power for them in a post-British constitutional framework, he sought almost until the very end, that these demands be met within a united India. He also strove for Hindu-Muslim unity with sincerity and conviction, more so in the early part of his political life (until the mid-1930s).

Never a religious fanatic, Jinnah presented the vision of a tolerant, plural, non-theocratic and democratic Pakistan after Partition became a reality. Jinnah is misunderstood in Pakistan because his vision for the nation challenges those who sought to Islamise it right from its inception.

After his death, within 13 months of Pakistan's birth, his enlightened vision left little influence both on the country’s internal nation-building process and its relationship with India. Since Jinnah’s successors wanted to make anti-Indianism the raison d’etre of the newly established Muslim nation, amity between the two neighbours — something Jinnah deeply desired — became a casualty.

There is a mountain of evidence to show that Jinnah was an Indian patriot for the longest period in his political life, until the final phase of the freedom movement when his politics took a communal turn. Briefly, here are some irrefutable facts.

a) Jinnah’s political guru, at the beginning of his public life, was Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a widely respected Congress leader. In his superb biography Jinnah: A Life, Pakistani scholar Yasser Latif Hamdani tells us that he wanted to be remembered as the “Muslim Gokhale, a voice of reason and moderation”.

b) Jinnah joined the Congress in 1906, whereas he joined the Muslim League only in 1913. Unbelievable though it may seem today, he remained an active member of both parties until 1921.

c) Jinnah, a rising star in Mumbai’s (then Bombay) legal fraternity, was the defence lawyer for Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak in 1908, when the British sent the latter to Burma for a six-year prison term on sedition charges.

d) In 1916 in Lucknow, he was instrumental in forging a historic partnership between the Congress and the Muslim League, which came to be known as Tilak-Jinnah Pact. Had its spirit survived, there would have been no Partition.

e) Addressing a meeting in Bombay in November 1917, Jinnah said: “My message to the Mussalmans is to join hands with your Hindu brethren. My message to Hindus is to lift your backward brother up.”

f) Pakistan-born historian Ayesha Jalal, in her widely acclaimed book The Sole Spokesman – Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan, tells us some revealing things about Jinnah’s thought process in the final years of the freedom movement. Initially, he was not in favour of Pakistan as a nation separate from India. He did not even like the word ‘Pakistan’. His true intention was not to have the kind of Pakistan that ultimately got founded — “a shadow and a husk, a maimed, mutilated and moth-eaten Pakistan” he called it in dejection — but a variant of Hindustan-Pakistan Confederation, which he preferred to call India. Remarkably, all through the Partition debate, he referred to India as the “motherland” of both Muslims and Hindus.

g) Even after Jinnah promised and demanded, Pakistan as a separate and sovereign “Muslim nation” for Muslims in India, he was also prepared to accept, at different points of time between 1940 and 1947, various kinds of federal or confederal constitutional arrangements that would keep Pakistan within India. For instance, in June 1946, he accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan proposed by the British, which specifically ruled out the partition of India. In June 1947, Jinnah proposed that the constituent assemblies of India and Pakistan should meet in New Delhi to give concrete shape to this plan. This was the last chance to keep India united. And Jinnah was willing to accept it. It is only after the Congress rejected the Cabinet Mission Plan that the Muslim League also withdrew its acceptance.

i) Jinnah is undoubtedly guilty of resorting to reprehensible and communal muscle-flexing, such as when the Muslim League (whose president he was) gave a call for ‘Direct Action’ on August 16, 1946. It proved to be a “black day” in the history of India, with mob violence plunging Calcutta into a whirlpool of murder and terror. More than 5,000 people, mostly Hindus, were killed.

j) Jinnah had several close Hindu friends. He poured out his unhappiness and agony before one of them, Ramkrishna Dalmia, a prominent industrialist of those times. “Look here, I never wanted this damn Pakistan! It was forced upon me by Sardar Patel. And now they want me to eat the humble pie and raise my hands in defeat.”

k) In his address to the All India Muslim League Council meeting in Karachi in December 1947, he stated: “I tell you that I still consider myself to be an Indian. For the moment I have accepted the Governor-Generalship of Pakistan. But I am looking forward to a time when I will return to India and take my place as a citizen of my country.”

l) Jinnah’s heart was not in his Government House in Karachi but in the beautiful mansion he had built for himself at Malabar Hill in Bombay. He wanted to return to Bombay and live in that house. An authentic and fascinating account of this is given by Sri Prakasa, India’s first High Commissioner to Pakistan, in his memoirs Pakistan: Birth and Last Days.

m) On February 26, 1948, Paul Alling, the first US ambassador to Pakistan, met Jinnah, who was then the governor general of Pakistan. He asked him: “What kind of relations do you desire between India and Pakistan?” Jinnah’s reply — “I want Pakistan-India ties to be as close and cooperative as those between USA and Canada” — is something that the people and politicians in our two countries should honestly ponder over.

The writer served as an aide to former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and is the founder of the Forum for a New South Asia