Miniature painting: Pakistan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Miniature painting

Miniature Aesthetics

By Amra Ali

To what extents have contemporary miniaturists been able to expand on the issues and aesthetics of their medium? Have they been able to synthesise from a language of the past to uncover new meanings in the present? These are some of the questions that should be asked of these artists and their art. To understand the progression of miniature after it became such a hot commodity internationally, it is necessary to know what has been demanded of the medium, first, by the artist and second, but of no less importance, by the art market. Who and where is this market? To what extent is the ‘work’ that is called miniature the product of market demand?

There is, of course, the prime example of Shazia Sikander, who made it big in the international art circuit. The mere name of MOMMA New York and big museums in the West that embraced Shazia’s work opened new avenues for other miniaturists from the National College of Art, Lahore. It has to be more than just being at the right place at the right time for these successes, because the exponents of what has been called the ‘Neo miniature’ school, like Imran Qureshi, Nusra Latif, Tazeen Qayyum and Aisha Khalid and others, seem to have addressed audiences not only internationally, but have found a following among younger graduates at home: some who have cashed in on the formula of the miniature aesthetics for sales alone; others, who are using it as a tool to comment on the socio-politics as it relates to this region.

Despite the fame and sudden popularity of Pakistani art due to the international interest in the miniature, which has often overshadowed multiple concerns within it, there are other dimensions to miniature, such as a subtle commentary on Western rules of aesthetics through constructing frameworks that chose to question these ‘established’ norms. The vocabulary that started brewing since Zahoor Al Akhlaq began his dialogue with the miniature suddenly exploded probably because there was a space needed for the Pakistani artists to look within, and to find a language that was situated in the present, but took its inspiration from the traditional aesthetics from their own cultural past. Writers have criticised these artists as having created a false perception, by unnecessarily drawing from a time period in history that is dead, claiming that the only reason for revisiting the Mughal Ateliers has been to gain entry into the international art market that chooses to slot Pakistani artists into that of the ‘other’ or the ‘exotic’; hence keeping it contained within the parameters defined by the West and denied it access or entry into the mainstream.

Back home, galleries in Karachi continue to exhibit the work of a growing number of miniature graduates, as more institutions integrate this genre into their curricula. Karachi remains the economic and cultural hub where new entrants gain their first exposure to a growing community of collectors and writers on art. Recently, Chawkandi Art Gallery in Karachi exhibited the work of two miniaturists from the NCA, Asif and Sobia Ahmed.

Asif’s vocabulary takes reference from the Kangra School in a very strict allegiance to the original framework of the art form. Not only does he insists on the importance of technique and skill, but makes a point of choosing to remain well within the traditional boundaries of original miniature. There are two schools of practice of the miniature originating from Lahore, one of the old school approaches of adhering strictly to the original and the other more experimental of artists like Imran Qureshi, whose vocabulary expands to deconstruct/reconstruct the original, and incorporates installation, sound and 4-D space. Although Asif’s work and approach can be located somewhere close to the

first, he makes an interesting point that he would prefer to continue to perfect his technique and wait for a change or transformation to happen spontaneously over time; he does not believe in approaching social or political issues, as that, he says, has also become an expectation and a formula for Neo-miniaturists.

His current body of work deals with the theme of love. Reference to cupid, some times a rose, strings, and rain drops drawn in the Kangra style, are the main imagery around which his compositions are arranged. The god Krishna emerges as another repeated visual element. The haashia or the frame remains consistently uniform, serving its presence as a rule to be followed, rather than an element that could be explored beyond its original structure. This is where one can see the deficiency within miniature today: the primary purpose of the artist has been to paint a picture with the main emphasis on skill rather than on a conceptual dialogue. The past and the present may coexist in a harmonious arrangement of colour and form, but whether or not they should be doing something beyond, is an important question to the artist. What is his point of view? This is the point that seems to separate the more innovative and the ‘copyists’, although Asif’s cautious and slow approach could prove to be an asset in being able to discover something more original and his own. There is, of course, the danger of him relying totally on his craftsmanship and skill that he seems to have mastered already, in producing paintings that will sell well to decorate drawing rooms, and only that!

Sobia Ahmed, who also shows at the same exhibition, uses the imagery of a girl, a cat, crows, leaves, trees and roots. Her narrative is more fluid compared to Asif’s and her frame merges, sometimes dissolves, with the rest of the page. An intentional way of addressing the frame, Sobia’s approach can be read as a more playful and humorous response to traditional miniature. There is something more than the sacredness of miniature which makes this body of work more appealing, because there is an awkward ambiguity that suggests that the artist is engaged on more than just surface decoration. It is this ambiguity that can help explore new dimensions to this art form, be it for the local, Diaspora or the international audience.

Miniatures, Modern

Modern miniatures

By Rumana Husain

In Amna Hashmi’s miniature paintings, details of fragile flowers, water droplets, wings of elves and fairies shimmer gently, bewitchingly, with delicate, pastel pigments going from light to dark in three out of her six paintings (gouache on wasli). The seventh miniature (tagged as number one) was missing from the recent show, apparently sold and gone before it had even reached the gallery. Some probable and mostly fantastical figures boogie from one painting to the next, proving the artist’s love for myths and legends. She is storytelling, elucidating on the magic and fear evoked by ‘The Moon’ — the title for her show — and has the following to say:

“…the moon has always been there, ordinary yet beautiful, a thing of wonder to whomever beholds it. And with time, many ideas have become attached to it. These paintings seek to capture the various stories that always crop up in one’s head, of ghosts and djinns, assassins crawling through the darkness, and minstrels singing songs, fairies playing in the gardens.”

Hashmi — a Bachelors degree holder from National College of Arts (NCA), Lahore (class of 2005), was showing her works at Chawkandi Art, Karachi, from July 23 for a week, together with two other colleagues: Abdul Rahim and Amjad Ali Talpur, also graduates of the same college.

Compositions from ‘The Moon’ series in the three dark (Prussian blue) works: ‘The Wolf’s Howl’, ‘Ambush — The ghosts’, and ‘Ambush — Assassins’ have strong compositions but fewer elements. The lighter coloured, minutely detailed works, ‘Ambush — The King’s Men’ (priced at a staggering Rs. 85,000) and ‘Fairies’ Hour’, have all the trappings of exquisite children’s book illustrations similar to illustrators like Arthur Rackham, Anne Yvonne Gilbert, Mabel Lucie Attwell, etc. of the Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or Hans Christian Andersen’s The Tinder Box, The Wild Swans, etc. or the Grimm’s Fairy Tales, including Rapunzel, Hansel and Gretel and many more. As we know, all these wonderful tales were produced in the second half of the nineteenth century — the golden age of children’s literature in England and the United States. First-rate writers teamed with first-rate illustrators to produce these books. The industrial revolution led to advances in printing and books became colourful and affordable.

However, the obvious influence of earlier as well as contemporary foreign illustrators on Hashmi, including perhaps Iranian as well as Japanese illustrators, (Japan’s massive output of Manga comics, which accounts for an overwhelming forty percent of everything published each year in that country has become a global phenomenon), one is left wondering why she has chosen these themes that are alien and has not utilised her exceptional and excellent skills in developing a body of work using characters and elements from ‘our’ part of the world. Portraying, say the Tilism-e-Hoshruba, the grand epic consisting of seven volumes (with one chronicle of the Dastan of the legendary hero Amir Hamza, which itself runs into forty-six daftars) Hashmi could find a wealth of themes for her miniatures. Those stories are also replete with fearless princes, who, with the help of ayyars — tricksters —fought evil kings; encountered and vanquished fiends, magicians and djinns and also courted beautiful princesses, miraculous enchantresses or parizads. The Hazar Aur Eik Ratein too, with its wealth of narratives including Aladdin, Ali Baba, Sindbad, etc. told by the witty Scheherazade, could engage the artist, challenging her to come up with innovative and contemporary interpretations of those stories for her miniatures. The other, more pertinent question is whether she is a painter or a children’s book illustrator?

Similar to Hashmi, who has participated in group shows since last year, Amjad Ali Talpur has also shown his works in group-exhibitions in Karachi and Islamabad. In the exhibition at Chawkandi, he showed thirteen miniatures, each one priced at Rs. 25,000. He has a restrained colour palette, and each work is approximately 4” x 5” in size — almost all portraits in profile — that are made up with one inch by one inch tiles that have a somewhat raised body of their own. Some of the tiles are placed slightly askew like in a board puzzle. No wonder then that the title of this series is ‘Game is over’, providing a pun on the turbaned (in the style of the Moghul kings’ costumes) and helmeted (armoured, military costume) men in history who belong to this region, and whose time has been up a long time ago.

But is it?

Talpur’s miniatures, in the style of the ‘badshahnama’, are quite well executed but nevertheless repetitive and lackluster. A series like this one could perhaps challenge the ingenuity of the artist if, while retaining the emphasis on portraiture, an evolving account could also be manifested.

‘Neem Rang’ — the title for the works of the third artist, Abdul Rahim, who hails from Gilgit, personifies worship and pain in the form of man, angel, yogis, a starving Gautama Buddha — seeking divinity by negating one’s self.

Rahim has done a variety of jobs and free-lance works, such as working as an illustrator for an NGO for mountain women’s development, or as assistant set designer for a five-star hotel in Islamabad, as painter and sculptor working with army aviation, as armour and costume designer for Anarkali — a music video directed by Shoaib Mansoor, and a props designer for yet another music video, Na re na, directed by Saqib Malik. Since the last one year, he is teaching at the Central Institute of Arts and Crafts (CIAC), Karachi.

Rahim’s compositions are separated strictly into sections — mostly two planes, with a vertical or horizontal division: one being the celestial; the extraterrestrial space which man aims to go to for eternity, in which a large sphere depicting either the sun or the moon dominates the space. The other is the earth; the ground, the soil, the dirt from which man emerges and in which he has to return before embarking on the next journey. The artist’s vocabulary is limited to a brooding, reflective man in most of the miniatures, with grids, cubes, clouds, water lilies and other plants sharing these spaces. In ‘Untitled’ and ‘Pain’ his skilful rendering of the male nude is evident. Works such as ‘Transformation’, in which a yogi is shown sitting on the edge of a cliff, with lilies floating in a linear pattern in the background and some of the pink-coloured petals are airborne, connecting the meditative man with a tiny sphere up there, somewhere, interesting stories are building up. In the absence of the artist’s statement, I can only conclude that Rahim practices yoga himself, and transcending the inner-self, harmonising one’s being with what is around, are personal experiences that he is attempting to express through his works. On the whole, while his works are appealing at a conceptual level, the execution in some of the paintings is want of more attention to detail to hold a viewer’s interest as well as fascination for the theme, which he is just beginning to explore.

Miniatures, Neo

Neo miniatures

By Amra Ali

Contemporary Miniature continues to evolve its vocabulary in order to find new locations of viewpoint and accessibility. It has for long sought to move away from its traditional framework to embrace contemporary ideological and structural realities, and found its ultimate location in an embrace within the global hierarchies of art making.

The bond with tradition translates into the use of the age old wasli used in the Mughal Ateliers. Rich embellishment in gold, decorative and intricate patterning and meticulous attention to detailing are some of the elements that affirm a continued engagement with a past. Yet, the distance covered is a move beyond the mere reclaiming of the past; it asserts a specific cultural baggage that enables it to enter the global network of art while returning to what may be a question of identity or of fragmented identities.

The decorative poses problems in terms of interpretation. Interpretation from within, which sees Miniature being used to gain accessibility outside Pakistan for its obvious, exotic appeal. That it reinforces the Western bias to categorise the ethnic and box it. Yet, the evolving directions within this genre provide room to access issues of identity, to question the very structures that provide it with prestige and exposure within an international market. It questions stereotypes through its stereotypical ‘look’.

The repetitive appearance of the military camouflage in the works of Imran Qureshi and Aisha Khaild shapes a narrative that attacks the hierarchies of racism and neo-imperialism post 9/11. If it uses technical expertise to seduce, one need only look beyond the pigment to find jarring voices of dissent and protest that question the new frameworks of exploitation and growing misinterpretation.

Imran Qureshi recently showed select works at the Canvas Gallery, Karachi. The works were part of a larger show held recently in Hong Kong, and at the Modern Art Oxford, UK. Entitled ‘Enlightened moderation’, the original show comprises of an installation of painted motif in blue that travels from the walls onto pillars and beyond the walls. We saw the emergence of this idea at Imran’s work in the inaugural show of the National Gallery in Islamabad earlier this summer. At the Singapore Biennale in 2006, Imran’s work, in situ, involved the painting of a wall outside a mosque, down its water pipes. His patent blue washes symbolising water and pattering of leaves made connections both within the spiritual context of purification, as well as a larger statement on the polluted waters of the world. These are issues that diffuse national and cultural boundaries, because the participants are the people of a global world.

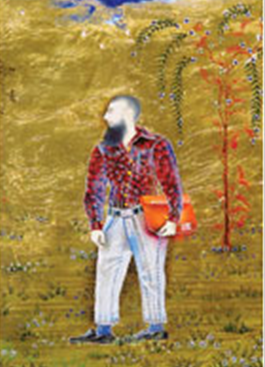

In the recent show in Karachi, viewers got to see a slice of the works that travelled outside Pakistan. Through images of bearded men in shalwars that end above the ankle, there is a continuing narrative through caricature, as well as a more serious look into prevailing confrontations between the religious right and the ‘enlightened moderates’. It is a grim reminder of the current climate of national crisis and the pivotal role of Pakistan in America’s war against fundamentalism. It gives a human face to the ruptured and caricatured identities of ordinary people caught in someone else’s war.

His lyrical line and a very subtle voice engage the viewer into a conversation that emerges from our shared life experiences.

The works simultaneously reinforce the meticulous detailing and aesthetic sensibilities of traditional Miniature painting. Could it be that the artist too remains at the risk of getting seduced by the perfection and beauty of his own line and technical expertise? The work of art is a piece of beauty, decoration and prestige (gold leaf), playing a layered role as it relocates the old in the new.

Finally, the paintings priced as high as Rs700,000/-, are far beyond the reach of but a few seriously rich buyers. With the entry of many miniaturists and other Pakistani artists in the international circuit of galleries, agents and biennials, it will affect the local markets and slowly restructure that way we address issues of art and aesthetics. It may also prompt many artists to wake up to unaccustomed rules in order to adjust to new frameworks of success. Whether that may be a heavy price to pay in the pursuit of original ideas or not, remains an open question. As for miniature, it can play a pivotal role in addressing issues of inequality and imbalance of power and carve new directions for its practitioners, both at home and abroad.

Along with the works, this exhibition saw the launching of publications on Imran Qureshi and Aisha Khalid, a sumptuous collection of their portfolio images and essays by Virginia Whiles priced at Rs3,000/-each.