Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Sources of this article include:

From the archives of “The Times of India”: 2011

The Times of India, Sep 23, 2011

Contents |

A timeline

Born : 5th Jan, 1941

Nicknamed : Tiger Ninth and last Nawab of Pataudi

School : Welham Boys (Dehradun), Lockers Park Prep School (Hertfordshire)

College : Winchester College, Balliol College, Oxford

December 13, 1961 : Makes debut against England in Delhi, scores 13.

January 10, 1962 : Scores maiden century in his third Test, 113 against England in Chennai.

March 23, 1962 : Leads India in his fourth Test, in Barbados, thus becoming Test cricket’s youngest captain at the age of 21.

February 12-13, 1964 : Scores career-best 203 not out against England in Delhi.

February-March 1968 : Leads India to their first overseas Test victory in Dunedin. India go on to win an away series for the first time, beating New Zealand 3-1.

January 23, 1975 : Plays his final Test match, scoring 9 in each innings against West Indies in Mumbai.

1964 : Arjuna Award

1967 : Padma Shri

A profile

He was an astute leader of men. Pataudi was thrust into captaincy mid-series against West Indies in 1962 when only five Tests old and 21 years of age after then-skipper Nari Contractor was struck in his head by a Charlie Grif fith delivery that nearly killed him Pataudi captained India for the next eight years. Under him, India won its first Test series abroad, a 3-1 against New Zealand in 1967-68

Equally importantly, under his tutelage, the famous Indian spin quartet earned their spurs and honed their craft, although the larg er rewards came to his successor Ajit Wadekar. “He was a bowler' captain. And he was always cool under pressure,” recalls fellow Test cricketer Abbas Ali Baig.

It was at Pataudi’s insistence that the gifted Gundappa Vish wanath got an early break in Tests A terrific fielder in the outfield, he was one of the first skippers who emphasized the importance of field ing and worked on improving it Under him, Indian cricket took its first steps towards the modern age

The Nawab, whose father too played Test cricket, albeit for Eng land, led India to nine victories in 40 Tests. In today's context, such an achievement might appear mod est. But as Mihir Bose writes in A History of Indian Cricket, “To a na tion that for 20 years regarded a draw as a victory, and whose crick et had a certain predictability, he brought the prospect of victory, of ten unexpected victories, and his captaincy had an element of dar ing, at times maddeningly unpre dictable, so that even when India failed the impression was of hav ing attempted the impossible.”

Contribution in cricket

The Times of India, Sep 23, 2011

EAS Prasanna

MAK turned Indian cricket around

He was an excellent gentleman and an exceptional human being. On the field, he was the one who turned Indian c r i cke t around. It seemed like a Mumbai team earlier but he gave it an all-India look. I remember he took over in 1961-62 from Nari Contractor and turned things around. He ensured a fair deal for everyone and made people more confi dent about themselves and their abilities. Surely, he was one of the best captains India ever had. He was also the one who made the world realize that Indians could field.

As far as I can remember, he fielded in all positions. He lost one eye but still was amazing in the field. I could never make out how he managed to be so good despite seeing with only one eye. He showed us the way to field. He handled me superbly. He un derstood me as a person and a play er. He also understood what an off spinner can bring to the team and used my skills well. He was an inspiration. He will be sorely missed. (As told to Satish Viswanathan)

Heights

The Times of India, Sep 23, 2011

By Abbas Ali Baig

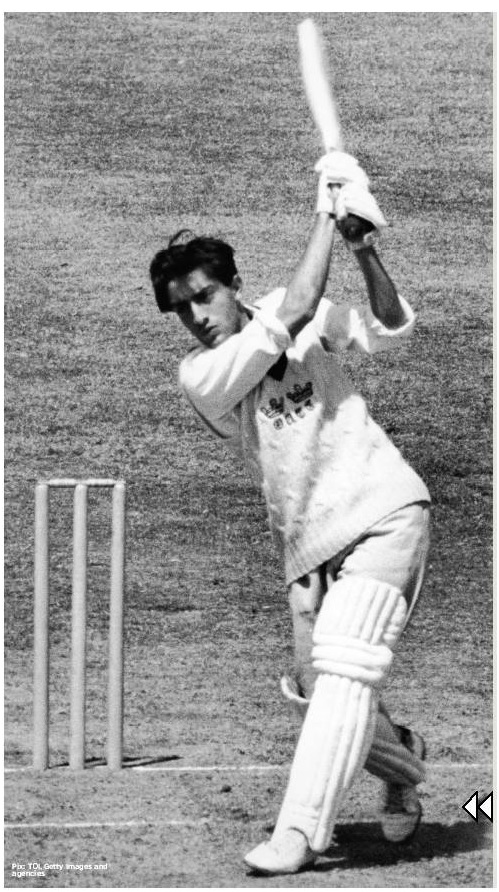

In the early 1960s, Tiger and I played together at Oxford, and our friendship was cemented over the past five decades. He was always full of life. It was painful to see him in the ICU. As a batsman, he was special. He could convert a good length ball into a half-volley and smack it out of the ground. Despite the nagging eye injury he suffered in a car accident, his reflexes were sharp enough to negotiate anything that bowlers could hurl at him. One recalls his magnificent 148 against England at Leeds that came in adverse conditions. God knows what heights he would have reached with two good eyes. He was an instinctive leader to begin at Oxford and in his early years as a Test captain. But in time, he became a much more thinking captain. Under him, the spin quartet blossomed.

He was a major star. His personality — a combination of style, background and ability — made him special. (As told to Avijit Ghosh)

His authority and elegance

By Ajit Wadekar

Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi, whom we referred to as “Pat”, was the first Indian team captain I played under, and also the last. He was also instrumental in me getting into the national team. It was he who suggested my name to Madhav Mantri and insisted that I be given a chance. Later, we became teammates and very good friends. Tiger brought about a phenomenal change to the Indian team's approach on the field. I think it was because he had spent his young days in England and had no complex against white skin. It was his authority and elegance that percolated down the team and made other players believe in themselves. Pat never felt inferior.

He was also one of the greatest batsmen that Indian cricket has seen. There was a unique character about his genius. He could pick any bat and even at times a left-hander's batting gloves and go out and perform with amazing ease.

It was a total surprise when the time came for me to take over from him. It was at the Cricket Club of India and we were playing a league match. Later, when Pat was having a glass of beer I asked him if he would have me in the team for the West Indies tour (1971). He replied, “But if you become the captain please ensure that you include me.” (As told to Vinay Nayudu)

Country before self

The Times of India, Sep 23, 2011

By Bishan Singh Bedi

There is an important reason why Tiger Pataudi stands head and shoulders above every other Indian cricket captain. He was the first man who brought into the dressing room a sense of ‘Indian-ness’, a feeling of belonging to, and playing for, a country. This is something which is hard to put in words, but everyone who played under him would sense it and be on their toes. Before him, the Indian cricket team used to be a mere, loose congregation of people from Bombay or Chennai or Punjab. Under him, players first learnt to put country above self. It’s an intangible but priceless contribution.

Significantly, he achieved this by being an ‘outsider’. His upbringing ensured that he always stood apart from those around him. Yet, he was humble to the core. He never wore nationalism on his sleeve. Not for him the usual manipulation, intrigue, favouritism or parochialism. Under him, the cricket team became one of the first national institutions to run on merit, and merit alone. Given the ground realities, it was also a battle Tiger could not always win.

This sense of rising as one for the nation entailed imbibing some other qualities. For one, Tiger hated over-the-top celebrations. A groundbreaking knock, which would leave everyone else breathless, would be followed by a mere nod. He wanted us to treat success like it was a part of life, not a rare occasion which needs to be marked by wild revelry.

He would also, as captain, be willing to risk defeat while chasing victory, again a very un-Indian trait in times when a draw was like a win for us.

Tiger had his ways of making sure everyone understood which page he was on. He had a very balanced head. He would never panic, scream or shout. Everyone who crossed the threshold into the dressing room would be accorded enormous respect.

When I made my debut under him in Kolkata in 1966, I wasn’t even in the main squad! Yet he made sure I would play. He told me I would do well, but sternly pointed out that I would be there on merit. It should have scared me, but I felt a strange confidence.

He lived a full life, and remained a prankster throughout. He had a contagious personality. He has no peers. (As told to Partha Bhaduri)

Tiger donated his good eye

Pataudi expressed desire about a week before death

Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi conquered world cricket's most fearsome bowlers with one good eye. He is no more but the eye will continue to live, because the legendary cricketer had decided to donate it. Dr Sumit Ray, vicechairman, critical care medicine at Sir Ganga Ram hospital, where Pataudi breathed his last, confirmed this.

He said that the left eye of the legendary cricketer was retrieved within hours after his death — with the family's consent — and has now been preserved in the hospital's eye bank. Pataudi's right eye was damaged permanently in a car accident when he was 20 years old.

“Pataudi had expressed his desire to donate the eye about a week ago when he was fully conscious. On Thursday morning, his wife Sharmila Tagore informed us about it. Accordingly, the family's consent was taken and after his death the organ was retrieved,” said Ray.

He added that no decision has been taken yet on who the beneficiary would be. “His eye was fully functional and it can be transplanted,” said another doctor. The 70-year-old cricketer was diagnosed with a debilitating lung infection — idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis — at Sir Ganga Ram hospital few months ago. No reason could be cited for the disease, which is irreversible in nature.

The Nawab’s Court: Bhopal

Atul Sethi | TNN

The Times of India, Oct 9, 2011

Pataudi’s uneasy ties with Bhopal, his mother’s hometown, had a lot to do with the legal battles he was mired in

Besides being the erstwhile nawab of Pataudi – a title he inherited from his father – he also got the legacy of the royal family of Bhopal – through his mother Sajida, the daughter of Hamidullah Khan, the last nawab of Bhopal. A legacy that over the past few years has been embroiled in messy legal battles that do not seem to be ending even after the dashing cricketer’s death. A large part of the litigation has involved Pataudi, his two sisters and their families. Sources say that a few years back, Pataudi is believed to have become so fed up of his property issues with his sisters that he wanted to have nothing to do with Bhopal. “He told us that he has nowhere to stay in Bhopal now. He wanted to finish off from the city,” says a source close to the family.

Despite his legal tangles, the erstwhile Nawab was quite fond of the city of his ancestors. Old timers recall his efforts to boost hockey and starting a cricket tournament in his father’s name where the likes of Sunil Gavaskar and ML Jaisimha came to play. He also briefly shifted to the city from New Delhi when he got son Saif admitted in the local Bal Bhavan school. Then, there was his love for Bhopali dishes like rizala as well as his penchant for playing bridge here. Rajdeep Singh, Pataudi’s bridge partner, recalls him as a decent player, whose “famous dry wit and laidback humour was often on display during the sessions.” He also liked to catch up on local banter. Anwar Mohammad Khan, his close associate for the past 25 years recalls going to the railway station once to pick him up.“Due to some confusion, I couldn’t meet him. But he simply hailed an auto and arrived at his palace, merrily chatting with the thrilled autowallah.”

After Pataudi’s death, there is still a bit of ambiguity on the family’s plans in Bhopal. The Pataudi children have had an on-off relationship with the city, even sometimes being accused of choosing to remain outsiders even though their family’s connections with the city runs deep. A few years back though, Pataudi nominated daughter Saba as his successor in managing the Auqaf-e-shahi, the charitable waqf trust set up by the Bhopal royal family. Royalty watchers feel that this was a prudent move. “As mutawalli, Saba would ensure continuity of the role of the Pataudi family in Bhopal,” says Syed Akhtar Husain, author of “Royal Journey of Bhopal.”

Many are now also hoping his other two children, especially Saif, take an active interest in consolidating the family’s interests in the city. A maulvi at the massive Taj-ul-masajid mosque echoes what many in the old city feel. “Saif miyan bade aadmi hain. Agar woh Bhopal se aur nazdeeki se jurein, toh shahi parivaar ke kaafi masle hal ho sakte hain (Saif is an important man. If he associates closely with Bhopal, many of the erstwhile royal family’s affairs can be tackled).”

That may be wishful thinking. But well-wishers of Tiger miyan – as Pataudi was fondly called in Bhopal – would be hoping his successors put the past behind them and end the family’s long tryst with city courts.

A questionnaire

The Times of India, Sep 23, 2011

How did you get the nickname Tiger?

It was given to me by my parents when I was very young. It was perhaps my propensity to crawl around a bit too fast... People think I got the name in cricket but that is not true. The name was given to me much before I even set eye on the bat or the ball.

When you were 11, your mother sent you off to study in Winchester where you were the only Indian at that time. Was that intimidating or fun?

It wasn’t fun to begin with because in the 1950s the British had just left India. They still thought they had some proprietary interest in India or that they might return some day. But in those days if you were a good sportsman it made a big difference. Cricket was the main sport at least in public schools.

In 1961, you became the captain of Oxford cricket team and also signed for Sussex. Why Sussex?

I played for them in 1957 when I was in school. Our school coach was also from Sussex and since I was living in Sussex too, it made more sense. Apart from that Sussex had tremendous Indian presence with Ranjit and Duleep having played there.

And then that tremendous car accident when you lost your eye?

It wasn’t a very bad accident. Somebody just drove into us. It was just that a splinter went into my eye. It was pure bad luck. I lost my eye but didn’t lose sight of my ambition.

How easy or difficult was it to get back and pick up the game?

Very difficult. Try playing any game with one eye or even pouring a glass of water. You have to get used to it. Of course, whatever ambition you have personally, has to be brought down a bit. Had I been 28, I would perhaps have given up, but at 21 I wanted to fight the handicap.

And you did that in style. By the end of 1961 you were playing for India while still in Oxford?

It’s always a great feeling to play for the country. I actually had to leave college because of the eye problem. Back in India, people didn’t realize that I had had a serious accident so they said you are selected to play for India. I said fine, I will give it a try.

By 1962 you had become the captain of the Indian team. The youngest ever that India had. Were you thrilled, surprised or shaken?

Well it actually happened by default. The captain Nari Contractor was supposed to carry on for a few more years. But he had a serious accident so I had to jump into the fray. I must say that a lot of senior players did help me, though one or two were not very happy.

What do you remember most from your eight-year stint as captain?

I think the most enjoyable aspect of this was when India beat New Zealand in New Zealand. We had never been to New Zealand before. Most of us didn’t know where it was. It was the first time that we beat a team abroad. That gave us special pleasure. We used to win some and lose some. Nothing much has changed in Indian cricket.

Many feel that your greatest contribution was in nurturing the famous spin quartet. Did that just happen or was that a deliberate strategy?

It didn’t happen just like that. We found ourselves with three big spinners at the same time. We did not have a pace attack and they spearheaded our bowling... You give people with talent a role and they find their feet. The spinners did us proud.

In 1965 you met Sharmila Tagore. Do you remember your first meeting?

In fact she had come to Delhi. I was not there, she gave a call to my house. When I came back from England I came to know that she had called, so I went to Bombay and thought I should contact her. But I thought I had better think of something or she would think who this guy was. So I said I had got a few things for her from England. She seemed very interested and asked me to come immediately. That was it and then we went out for dinner.

You actually got a refrigerator for her from England?

Yes I thought that’s something she would be interested in.

Did you bowl her over?

I don’t think it was immediate. She batted quite well for a long time. Finally perseverance got through.

You are also a practical prankster. There was an amazing joke that you played on Prasanna and Chandra.

That was Madhavrao Scindia’s effort. It was in Gwalior. But yes, Prasanna was ‘shot’ by dacoits. He acted as if he collapsed. We put him in a van and took him away. It became very serious when both Chandra and Vishwanath started crying. We had to actually pacify them, we asked them if they wanted a brandy. They said, “No, coffee”. And that was at 4 in the morning. I remember Madhavrao Scindia saying “Where will I get them coffee at 4 in the morning”. We had lots of fun.

Some of your friends say that Tiger Pataudi would have achieved a lot more had he been just a little less laidback. Do you accept this?

Well, I have accepted a lot from my friends. One is a product of one’s time. If I were a little laidback, I am prepared to accept it but how much more I could have achieved by running around, I am not so sure. I am very happy as I am.

What excites you now?

I will tell you what really excites me – the sight of a wild elephant. With the ears and the trunk stuck out and coming at you. That really terrifies me and excites me.

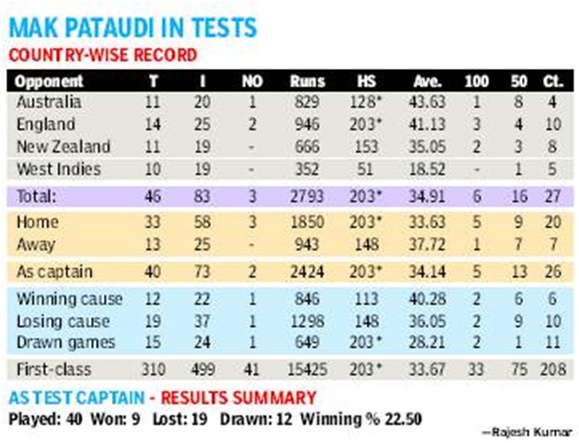

Over an international career spanning 15 years, Pataudi played 46 Tests, scoring 2,793 runs with six centuries at an average of 34.91 — all while batting with one good eye. A car accident in July 1961, six months before his Test debut, left him with a severely impaired right eye. But it didn’t stop him from being a regal middle-order batsman and a superb fielder. He also became India’s youngest cricket captain, at 21, after then skipper Nari Contractor was struck on his head by a Charlie Griffith delivery during a West Indies tour. He led India to its first Test series victory abroad — 3-1 against New Zealand in 1967-68 – and also nurtured the famed Indian spin quartet during the 40 Tests in which he led India.

Off the pitch, Pataudi’s aristocratic lineage and dashing looks ensured heartthrob status. His romance and marriage to film star Sharmila Tagore remains the biggest union of glamour and sports in modern India. Years later, Pataudi shot for ads with his son, actor Saif Ali Khan. Doting fans insisted he was still the bigger, better-looking star. For them, the Tiger was always burning bright.

India didn’t utilise Tiger’s services well: Chappell

[ From the archives of the Times of India]

Nitin Naik | TNN

It takes one natural leader to respect another. Hence, it was no surprise to see Ian Chappell pay rich tribute to the late Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi at the Raj Singh Dungarpur World Cricket Summit on Monday night. Chappell said: "Tiger's services could have been better utilised as an administrator. He had a wonderful knowledge of the game and had the ability to give more to cricket and life. I know he had some role to play in the IPL and was a match referee, but he could have been used more wisely given his vast experience as a player." “He was an interesting and thoughtful character and a charming personality who wouldn't say much. But whatever he said stayed in the mind for long," Chappell said.

He recounted Pataudi's aggressive knocks of 75 and 85 in the MCG Test of the 1967-68 Australia tour and revealed that Pataudi had played the game despite being only halffit. “He had a one-eye handicap and an injured leg. Throw in the inconsistent and overcast Melbourne weather and India's position of 25 for 5 and you can understand how grim the scenario was. He played both his knocks camping on his good leg, the back foot."

Chappell also recalled his extreme surprise at how during every rain break, Tiger walked to the middle with a new willow. When he inquired after the game at how he could play so well with different bats, Pataudi revealed he never carried bats in his kit bag. "He (Pataudi) told me that his bag for the tour included a sweater, a pair of socks, jockstraps and nothing else. The bat he picked up was always the one nearest to the dressing room," Chappell said. He had the gathering in splits when he recalled his ignorance about Tiger's family history. "My parents should have demanded a refund from the university where I studied as I asked Tiger what he did for a living. He just told me, 'Ian, I'm a prince.' Not getting the point, I repeatedly asked him what did he do between 9 and 5. He finally snapped and said, 'Ian, I'm a f*****g prince!"