Linguistic Survey Of India, 1927: Introduction

This article has been extracted from |

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, paragraphs might have got rearranged or omitted and/ or footnotes might have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these errors might like to correct (and/ or update) them in a Part II of this article. Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book. Thirdly, it might not have complete paragraphs. These are excerpts obtained through an Internet search.

Introduction

The languages of India have from the earliest times been an object of internet to Previous enquiries into those that spoke them,but their serious study by foreigners Indian languages.is not more than three hundred years old.Even the great Albiruni.

Albirlini in the account of the India. of his da.y (sbout 1030 A.D.) spoke only of SaID:Ikrit, then a dead language. and its difficulties. Regarding the living forms -of speech'- he merely said,! "Further, .the language is divided into a. neglected vernacular one, only in use among the common people, and a classical one, only in use among the upper and educa.ted classes, which is much cultivated." Amir Khusrau,a Turk by origin, but bom in Ind.ia, gives us (1317A.D.) more detailed information.' He says:-

As I was born in hind I may be allowed to say a word respecting the languages.There is at this time in every province a languages peculiar to itself ,and not borrowed from any sindi[i.e sindhi] lahori[Panjabi],kashmiri,the language of dugar[dogra of jammu],Dhur samundar[kanarese of maysore] tilang [telugu] Gujarat mabar [tamil of the coromandel coast] gaur [northern Bengali] benga audh [estern hindi]delhi and its environs [western hindi] these are all languages of hind,which more ancient time have been applied in every way to the comman purpose of life.

Eles where he speaks of hindi meaning by this term the languages of hind or india i.e probably Sanskrit and not what we now a days call by that name. If you ponder the matter well ,you will not find the hindi languages inferior to the parsi [Persian it is inferior to the Arabic ,which is the chief of all languages Arabic in speech Has a separate province and no other languages can combine with it.The parsi is deficient in its vocabulary ,and can not be tasted without Arabic condiments as the latter is pure and the former mixed you might say that one was the soul,and the other the body.with the former nothing can enter into combination but with late every kind of thing.it is not proper to place the cornelian of yemen on level with the pearl of dari.

The language of hind is like the Arabic ,in as much as neither admits of combination If there is grammar and syntax in Arabic there is not one latter Less of them in the hindi.if you ask whether there are the sciences of expositions and rhetoric i answer that the hindi is in no way deficients in these respects.whoever possesesses these three languages in his store,will know that i speak without error or exaggeration.

Here we learn much more than what we are told by Albiro.ni. The latter writes as

if one a.ndthe Same spoken la.ngll1Lv<>e was current over the whole of I ndia, though, no

doubt, he knew better. The other gives a fairly complete list or seven Indo-Aryan

'Ianguages with two dialects, and of thl"OO of the principal Dravidian formfl of speech.

Although he was not a. foreigne r, I may quote in thui connexion the words of Abu'l fasl in the • Ain-i-Akbarl ' .. upon the sa.me subject, for, while he W808 an Indian born a.nd bred, he did not look a.t matters from~ a Hindo. point of view;-

Here we have a somewhat fuller catalogue, though some important names,-----e .g. Tamil,-are omitted; but we see th8.t they are bare lists and nothing more, 8.nd I know of no early oriental account of the languages themselves, either as a whole, or taken individually.'

So far as I am aware, the earliest notice of the modern Indian languages that appeared. in Europe was in Edward Terry's 'Voyage to the East Indies,' published in 1666 A.D. He there informs us'" that • the Vulgar Tongue of the Countrey of Indostan hath great Affinity with the Persian and Arabian Tongues, but is pleasanter and easier to pronounce, It is a fluent language, expressing many things in a few words.3 They write and read like us, viz., from the Left to the Right Hand.' Some of the English merchants of those days could certainly speak Hindostani with fluency,4 and Thomas Coryate, when presented to the Great Mogul by Sir Thomas Roe, is said to have addressed that potentate in a Persian speech. So, Fryer5 (1673) in his ` New Account of East India. and Persia.' says regarding India. '

The langunge at Court is Persi4n. that commonly spoken is Indostan (for which they have no propel• chamcter, the written language being called BanYall). which is a. mixture of Per8ial~ aud Sclavonian, a.s a.reaU the dialects of India..'

Before Terry and Fryer, there had been descriptions of Na",o-a.ri. the principal written chamcterof Northern India. Thecelebrated. traveller Pietro Della Vallas describes it (1623) as 'ana.ncientcham.cter . kuown to the learned, and used.by the Brahmans, who, to distinguish it from the other vulgar characters, call it Nagheri.' Again, Father Heinrich Roth, who was a. member of the Jesuits' College at Agrn from 1653 to 1668, met Athanasius Kircher at Rome in 1664, and there gave him scveral specimens of the same character which the latter published in 1667 ill h.is 'China I llustmta..' One of these was the Patenl08tel• in Latin tmnslitera.ted.into Nigari. We shall see that formauyyears thiswa.s taken to be s,specimen ofactua.l Sa.nskrit.an languages

1.Before turning to European accounts of Indian languages i may mention legend concerning another and earlier linguistic survey currents among the afghan whose languages Pashto is admitted to be in harmonious .it is said that king Solomon went forth his grand vizier asaf to Collect specimens of all the languagues spokenon the earth .the official returned with his task accomplished.

In full darbar he recited passages in every tongue till he came to Pashto.here he halted and produced a pot in which he rattled a stone.that said he is the nearest approach that i can make To the languages of the afghans .it is plain that even Solomon with all his wisdom had not at the time succeeded in anticipating the methods of professor Daniel jones and of the International phonetic association.

2.Quoted from ogilby asia see below .much of what follows will Also be found scattered through the different volumes of the survey or in other writings of mine.the various statements are here combined into one general view.

3.Hindostani had this undeserved reputation for many generations.There is a story one of the First English judge of The Calcutta high court.in sentencing a man death he is said to have dwelt at length in English on the enormityof the offence the unhappy feelings of the criminals parents and his certain fate in the next worl unless he repented.when he had fineshed he instructed the court interpreterto translate to the prisoner what he said this worthy Translation consisted of the six words jao ,oadzat,phasi ka kuk Hua “go rascal,you are ordered to be hanged,

The judge is said thereupon to have expressed his admiration at the wonderful conciseness of the Indian languages.

4. Hobson jobson s.v hindostanee gives the following anecdote of tom coryate taken from terry. The occur woman a laundress belonging to that shemylord embassador house who had such a freedom and liberty of speech that she would some time scould brawl and rail from the sun rising to the sun set one day he undertook her in her and by eight of the clock he so silenced her,that she had not one word more to speak.

5.Also from hobson johson

6.viaggi 57.quatation taken from dalgados glossario luso asiatico s.v Devangarico.

to fill his bulky work with an immense amount of various and curious information. He was acquainted (pp. 129•134) with the South Indian method of writillg on palm-leaves by pressing in grooves with an iron stylus, which is the origin of the circular shape of the letters of the modern Oriya and other southern alphabets.

He then goes As to what 00"08I'Il8 the LaDguage of the Itulo" ...... , it"""ly diffem in general froro the Moon and Paasing over works such as HenriellS van &heedetot Drakenstein's • Hortus IndiCllS Malaba.ricus' (1678):and Thomas Hyde's work on chess, the • Historia ShahiludH' (1694), both of which conf&i.ned. specimens of the Niga.ri alphabet .... we next come to And.reas Yiiller'ecolIectionof versiollso£ tohe Lorn's Prayer, written under the pseudonym of Thomas Ludekene and published in Berlin in 1680.1 Ita full title is Oratio Orationu1n. S.8. Oratw,li8.Domi"icM Pers1{JneS praeter autMnUcam {ere centtm~, eiigue longe enlendatiu8 quam t.lfltehac, et e prQbali88imisA140ribu8 potius qua1H prioribEIs Col;ectionilJfls. ;amque Bi"Uv.ljj ge"uim"s Lit/guii Btl/iCAa~, ockoque tNagnom Parume:r .d eroe ad EdiliOttltn (I BarninlO Eagio trad,tae editoeque a Thoma Ludekenio, Solq. Marcl. Berolifli, ex OfficiflO Ruftgiat/a. Anno 1680. The "&rnimus Hagius mentioned herein as the engraver is another pseudonym of Muller himself. In this collection Roth's Paternoster W88 reprinted. as being actually Sanskrit, and not 1:1. mere tl1Ulsliteration of the Latin original.

the Elector at Bedin in 1697, aud died in that city iu 1730. This remarkable scholar. amid his manifold activities, was I:t. profound student of oriental lore, e.s it was then understood. and carried on a. copious correepondence with most of the learned men of Europe. This correspondence 1'"88 published in 1740246 o.t Leipzig in three closely printed Latin volumes, lilld is still oht:.a.Wahle in the book-lJUt,rket. In the year 1'7140 Wilkins wrote to him asking for help in the preparation of Cho.ffiberlayne's • 8ylloge.' This request incited I6Croze to write a. long communication' to Cho.mberlayne dealing with the general question of the study of languages, and vindicating comparative philology from the charge of inutility.

He then proceeds briefly to describ6 the inter-relationship of the varioU.II languages known to him. and, coming to India, /Jays, • I have, however, little to offer oonceming the alphabets of t his country, except that they are derived from t hat called Hanscrit: the source of t he ohlest forms of which is the [Semitio] alphabet of Persia or Assyria, and which is ustld by the Brachmans. From these Brachmans the other Indi&n tribes have imbibed their 8uperstitioUli, and it was o.mongst them that Xaca,' who laid the bonds of mise religions on the peaples of the East. was himself brought up. Thus, the order of the alphabet is the aa.me iIomongst the Bradulla.ns, the people of Malaba.r, the Singhalese, Siamese.

Jo.vans, and even t he language of Bali" which is the sacred. tongue of I.aos, Pegu,

Cambodia, and Siam." With a passing reference to the letters written to Ziegenoolg.

of the Danish Mission at Tranquebar, who was I.aCrot.e's chief souree of information

regarding the languages of southern India, we come to the latter's voluminous correspondence

with TheophilUli Siegfried Buyer, then residing in l'he most learued men of Europe, - including Bayer,-were invited to join it, and it WlUI filially put on a penruwent footing by Peter II. The first two volumes of the 'l'rnnsa.etions,

relating to the year 1726, were published in 1728, and are now very rum, nearly

the whole issue having been destroyed in a fire which consumed. the Academy. in 1741.

In 1727, Daniel Messerschmidt, who had been deputed by

Peter the Great to explore Siberia, returned.to Petrograd

.and, among other curiosities, brought with him I\ll iD8cription and a. Chin,*, printed

book. These were made over to Bayer, and he describes them in the third and fourth

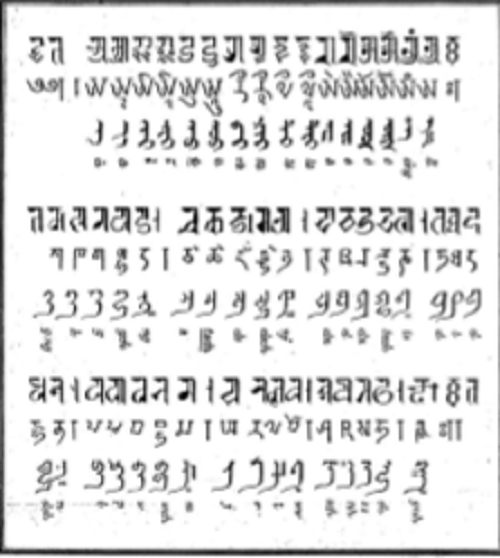

volumes of the Transactions. The iD8Cription consisted of two short lines, each in !\

dilferent form of the Tibetancharacl:.er. It•is reproduced.hcre.

Bayer, with the aid of the book to be subsequently described a.nd of his knowledge of Ml\nchu, deciphered thlli as ' Ong ma ni p6 dme ck'tun chi,' bllt was unable. to discover its moo.niug. Messerschmidt, he aa.ys, told him. that it WlUil one of the comme-nest pra.yers (If the Tunguts (i.l!!. Tibe~j and meant' GOO. have mercy on us.' This decipherment ot the well-known Buddhist formula Om, mati. padmi, hum, though its translation was in- correct, IlUtorks the first at.ep in a. new stage of the study of Indian languages in Europe. For the next few years European IIChol.a.ra attMked. the la.nguages of northern India. 'throughChineaeand'l'ibetan:

The other curiosity brought back by Messerschmidt.---a. book consisting of eight l eaves,- had been printed in China, and ma.y be looked upon. 88 the Rosetta. stoue of these explorers. It gave in pamllellines an entire syllabary of the 'l'ibetau IAnt8ha alphabet witb a. tmnslitemtion into ordinaq Tibetan, and into a. form of Manchu which Ba.yer called Mongolian. A facsimile of the first page I\lld eo half' u. given on the plate opposite.

1. The Ep La cri 16. 2. The Ep lacr i 23 iii,28 3. Pronouneed like the lines to a page abut three lines contain the complete of simple letter i have followed bayer in giving a page and a half on the plate.

Bayer'e flret procedure W88 to eetablieh .80 far as W&8 possible the Tibetan charactel'll. This waa an easy task. for the la.nguage was already partly known to him. and he had other Tibetan studentB and books athieoolD.lllllolld. Then, with the aid ofthielWld other apecimene. be established the Manchu tranellteration. and finally from these two. he was able to make a very fair attempt at transliterating the LAnt6ha., which is a kind of ornamental Niga.ri.. In the plate I h&ve given the tflUUliiterntion tlxed by him a.ud used for deciphering the Om. maltt padmi. hum of the inecription. It will hE' observed that the transcription is by no means fa.ultleu, though it is wonderful for 80 early an attempt.' Having thus made out the LAnt&ba. alphabet, Bayer sent a copy of it to Bcbultze, the missionary at Tranquebar. and Wall gmti6.ed to learn that tho lettel'8 could be rood by the Bmbmans of norlhern India!

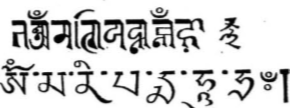

Schultze. hiPl8elf, to judge from the epeciwene he gives. ca.nnot at that time have known Sanskrit, or. indeed, much of any Indo-Arya.n language. He epelle the name • Beuares • ~ or ~ and talkBof "f11R:r. ~. He, however. describes three s,lphnbete s,nd gives epecimene of t hem • .........fhe Ni.g&ri. the • Balabandu,' and the • AkAr Na.ga.rl.'

They had evidently been sent to Bayer juet &8 they had been writteu down for Schultze, who could not. read them. By' Bal&bandu ' he meant Manlthi, but the three alphabets are all merely Nagarl written by different bande. Schultze 80180 gives inetructioll9 for .pronunciation. Some of tbem may be quoted' :- i breue,lingna.adderleramincliuata. ( longum, lingua ad einietmm mota. a breue. recto ex ore protruditur.

All this time he was conducting &Q active correepondence with LaCroze, in which not

only doee the Chinese book find due mention. but we moot one of the earliest n.ttempts

at genuine comparative philology in the modern IJCllSe of the term,-----a oompa.rieon of the

1irst fOllr numernl8 in eight different languagee.4 During the next ten yeal'8, the two

frieude now and then refer to Indian 1a.nguagee, and to the last La.Croze maintains the

eorreetnese of his thoory of the Semitio origin of the Indian Alphabet.

All this time,-indeed since the 16th ,centwy,-Southern India had been tbe IlCene of the aotivities of DaniBh and J esuit mwionaries. Schultze hall hoon already referred to more than onoo, and if I do not do more than mention t he names of such men as . Beschi, the Englishman Thomas Estevilo (Stephena) of Goa.. or (of the Danish .Mission at Tmnqnebar) Fliobricius and Ziegeubalg, it is ooly because theso great schola.rs are not properly connected with the subject under consideratioo,- tho history of the geueml study of In4ian langullcae8. They wrote grammars and dictiona ries or translated the .scriptures each in or into one or more South Indian Iangua.:",'e8, but they had no connexion ,with the study of Indian languages as a whole.'

Somewhat different is the case of the Roman Catholic Missionaries of Northern India. The Ca.puchin Missionary Cassiano Beliga.tti wrote a treatise on the Nig&d alph.a.bet, entitled. • Alphabetum Bnmunhanicum sev Industa.num Universitatis KaQ{ ' (Rome, 1771). The book it6elf would not deserve mention here were it not accompanied by a preface from the pen of Johaunes Chrilltophoros Amadutius containing a. very complete summary,

with copiousreferencestoauthoritie6,of the then existing 'knowledge regarding Indian languages. It correctly describes Sanskrit (written 13in'1~li"1') as the language of the learned, and next describes the "CIT ifill'!' or' Beka. Bon.' (i.e., IJhd,lW. IJoli ) or common tongue which is found in the' University of Ka.&l. or Benarl!s.' He adds that diffcrent regioD8 and different languages have their own a.lpha.bets, and among the la.llgU~ he enumerates (1) l3engalensis, (2) Tourutiooua [i .e., Maithili], (3) Nepa,lellsis, (4) Marathica., (5) Pegun.uu. [i.e., Burmese or Mon}, (6) Singalaea, (7) '1'elugica., and (8) Tamnlica.. This book is of further interest because t.he Nagari null Kaithl chara.ctersare set up in moveabletype.-the first to beused,I helieve, for t his purposcinEurope.

Btll the linguistic lea.rning of the 18th century, and forms

_8. link between the old philology and the new.

A consideration ?f this early stage of the enquiry into the languages of India. will scientific study. Such study could not, indeed ha.ve been expected in those days. necessary materials, though increasing gradually from decade to decade, were throughout too scanty-for it to have been possible. Nevertheless the period was marked by a steady advance in kuowledge beyond the older belief that all languages were derived from Hebrew. In the early years of the 1 '1th century the existence in India of Sanskrit, the sacred.litemry language, became known, and from this, as a sort of corollary. there arose the belief that besides it there was in addition one general colloquial form of speech used by the vulgar over 'the whole continent.

A further development of this belief was the etirious error that that colioquial language was Malay, a kind of lingua franca, before which the indigenous speech was disappearing. It took many -decades to wipe out this misapprehension and its COnsequences. The existence of more than onc spoken language waathenextdiscovery. Thiswnsfirstaasociatedwithcollectionsofa.lphabets.apparently as mere curiosities and without any reference to the la.ng~"'e8 for which they were mriployed. But the knowledge thus •gained of diverse alphabets led to a suspicion of the existence of diverse tongues. and this. in its turn, led to the making of colloctions of versions of the Lord's Prayer. at first full of blunders, but becoming more and more complete and more and more accurate as tbe years went on. These collections invited comparisons of their contents. and suggested the first beginnings of comparative philology It is at this stage that the great names of LaCroze and Bayer come into prominence.

They began to make rudimentary classifications of languages based on comparisons of the numerals and simihu words. and succeeded in tracing the connexion between the alphabets of Tibet and India, a fact which was destined in later days to have a far-reaching importance. They got into communication with the great pioneer missionaries of Southern India. and, with their help, enriched the mass of materials available for study. In fact. as- is shown by Amadutius's preface to Beligatti's 'Alphabetum Brammhauicum'. it wason their researches that all subsequent investigations of the period were founded; and it was by following their methods tI:iat Iwarus Abel and Adelung were able to make the great advance in scientific exploration that is associated with their names.

At the end of the period we find that Europe had a fairly clear idea of the names and general characters of the principal Indian languages,and that it.s scholars had begun to compa.re one, with another. The old philology thus on i4 deathbed gave birth to the new. 'I'be materials for classification had been collected a.nd set in order, but no geneml el.a.ssification had yet boon attempted.

- Modern comparativtl philology d.atea from the introduction of Sanskrit as a serious

object of study. and from the consequent recognition of the existence of an Indo-European family ,,?flanguagesbySirWilliam Jones in 1786. In his thin! Annual Discourse to the Asiatic Society [of Bengal]. deliveredinthatyear.hesaid':-

Here we have sPCCUlatiOIlB not only a.s to the modern vernaculars of India. (which Ilrc mainly erroneou8), but also as to tho connexion of Sanskrit with the languages of Europe: "'£hese latter speculations were converted into a scientific ccrtainty by the Jahours of Franz Bopp. whose first work,-Uebt:r das ConjugaliOlI8- system ckr SlIfltilkriUpracile in IT ergleichung mu jenem del' -griuhiachen, lateinischen, perriscktm wid gerf1kmisclu,. Spraclu.-appea.red in 1816, to be followed by hi8 epoch-making Comparative Gramma r, publi8hed in 1833 aDd the following years, Mld traIlBmted into Engli8h by E. B, Eastwick in 1865. The history of general Indo-European philology does not oonOOrn UlJ here. and therefore, in order to carry this particular branch of learning down to our own t imes, I do no more than mention t he names of Bopp's greo.t successors,-Grimm, Pott. Schleiche_r, Whitney, Brugmann. ])elbru.ck, )'Ieillet, and Jespersen.

Returning to inquiries into the modern langua.gus of India" we have soon t hat hero too the problem was originally laid down by Sir William Jonea, but u.ccompanied by speeulatioTIswhich subsequent resoorch has shown to be unfounded 90 far Wi! t he Indo. Aryan languages are concerned. Dravidian languages, a8 \.10 distinct group, were then unknown. but if he had• said about them what he did e rroneously say about Hindi, he would Dot have been far from what are now believed to have been the actual facts.

The whole discussion is too long to quote, but it is very interesting

rt>-B.dlng, especially as it is the first attempt at a systematic survey of the langruiges of

India. In this connexion, it is well to remember that its date is 1816, and that ita

authors were Carey, Marshman. and Ward. The In.ngua..:.<res considered are as follows (I

give the original spelling) :-Sungskrit, Bengalee, Hindee, KaBhmeera, Doguta [i.e.

- pogrl], Wuch [i.e. Lahnda], Sindh, Southern Sindh, Kutch, Goojurat.ee. Kunkuna.;

Pllnjn.bee or Shikh, Bika.ne~r, Mamwar. Juya-poora, Ooduya-poof8., Harutee, Maluwa, Bruj, Bunde~khund, Mahratta._Magudba or South Ba.har, North KashulI' [i.e. Awttdhil,. Mythilce, Nepal, Assa~. Ol'issa. Ol' Ootko.d, Telinga., Kurnat&, Puahtoo or Aflghan,_ Bulochee, Khassee; Burm!Ul.

This list is irulhuctive in. two points. In the flNt placc it shows that; the Dravidian laoguagea-Tam.il, Telugu, Ka.na.reao, and so forth-were not yet recognized 8.8 asepe.m.t.e family. That had to await the acute discernment of Hodgson. Here they Me looked upon &8 being just u.s much Sanskritio 8.8 Bengali or Hindi. The other point is that no distinction ha.s been made between la.nguage 'and di&lcct. We ftud great languagea,-like Burmese, Bengali, or P8.fQ,to-side by side with forms of speech like J aipuri and Ramuti, which are hardly separate dia.leets- certa.inly lese 90 than the dialect of Somer& etandtba.t ofDevonshire. This is due to the fact that, at least in Northern India." there is no word exactly corre8ponding to our 'language,'• a.s distinct from' dialect.' All that the a.verage Indian recognizes i8 diaJect. Unleu taught by BuropE'au methods, he has no word for denoting a. group of cognate dialect. under one general hE'ad. He haa numerous (hundreds of) dialect names, just as we talk of the Somersetshire and Yorkshire dialeets, but no word parallel to our general term, 'English.' With Carey's report, further inquiry into the general relationship of the Aryan languages of India seems to have been dropped for a considemble period. The latelyformed Asiatic Society in Ca.lcutl;& was too busy with the study of Sanskrit and Persian to trouble much about the modern vernaculars. Practical gmmmars of the more imporlant languages were, it i8 truc, compiled in plenty, but there was at first no co-ordina.

(Vol. V.) 0. Comparative Vocabula.ry of some of the la.nguages spoken in Burma, a.nd three years Ia.ter D. J : Leyden. in the tenth volume, wrote on the Language and Literature of the Indo-Chinese No.tioDs. Ago.in, in 1837. in Volume VI of the Journo.l of tho Asilltio Society of Bengal, we 'have a. comparison of the Indo-Chinese languages by Nathan Brown, who was a lso the author of other pa.peN connected with the same subject which later appea.red in the Journal of the American Orienta.I Society.

In 1828 (Asia.tio B.aea.rohes, Vol. XVI) we first meet one name that overshadows all the rest,-that of Brian H oughton Hodgson,-as the a uthor of o.n article on the Language, Literature, and Religion of the Bauddhas of Nopi.l and Bhot (Tibet). This was followed by & long series of papeN on the zoology and ethnology of Nepal, hut, nineteen years afterwards, in 184.7 (Journa.l A. S. B. Vol. XVI).

he resumes bis philological enquiries, with & Comparative VocabuIa.ry of the Sub-Himalayan dialecta. Then followed a number of important papers, still clo.ssics, and 8till [ull of varied o.nd accurate inform&tiou regarding neo.rly every non~Aryan language of Indio. and the ueighbouring countries. Spa.ce will not allow me to give even & dry ea.ta.logue of the subjects which he adorned. Suffice it to 8&y here that he g&ve comparative vOC&bu~ laries of nearly all the Indo-Chinese languages 8poken in Ind..ia and the neighbouring coWltries, and of the MtlQ4i IUld of the Dravidian forms of 8peech_ These he compared with many lo.nguo.goo of Central Asia in the 8e8.roh of one common origin for the whole. So far as I a.m-a.wa.re. he was the finJt EnglishlUlWl to use the term • Dravid..ian' for thelanguages of Central and Southern India, but be included. under that term not only the Dravidian Janguage8 proper, but also those of au o.ltogether different fa.mily,-tbe MW).4i. It iii true that he fa.iJ.ed to Jl8ta,blish his fa.vourite theory of a. common origin fflt' aU the la!lgua.ges explored by him • .....:.that is A. matter still under inquiry, IlDd DIi 1< w:h iob the (>p~0U8 of 8O no1&1"8 are still divided,-but this hardly diminishes the value of his wri t.ings. which. contain "tlUl88 of evidence on the aboriginal llWlgWlg6B of India. that baa never been superseded. I ts h&U•marks a.re the wide extent of a.rea covered. ~l6t\rnesa cf arrangement, and.&oouracy of treatment. Hodgson's laB!; paper on Indian languages, on the languages of the broken tribes of Nepa.l. appeared in 1858. in the twentyseventh volume of the Jow-no.l of the Society with which he was so intimatelyoollneeted.

SO that his liter&ry !\Ctirity covered justthirty years. l'en years later, in 1868. there

HIl~_. appeared Hunter's" Comparative Dictionary of the l&n~es

of India and High Asia". which. with some additions, summarized the reeults of

Hodgson's linguistio collootions. and presented them in a form convenient to the atudent

The, earliest fruit of Hodgson's researches wa.s Miu: Millier'a Letter to the Chevalier

Bunsen, p ublished. in IBM. In this Minier established, for

the fir"llttime,tbeexWtence of the MUJ;I:!Ji' fa.milyof languagee:

fl8anind.ependentbodyofspeech,a.pa-ttfmmthe D ravidiaD,

Nld gave itana.me. Twoyoo.l'lllater, in 1856,appeared what has ever since been

the foundation of resea.rch into the tongues of Sollthern India, Bishop Caldwell's ' Com-

Cakt_Il. Dravld1&n Lan.. parative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian F amily

aap&. of Languages.' Here, for the first time, a. group of Indian

languages W8.8 treated fl8 a whole by a scholar who waH practically familiar with its elementsandatthesa.

metimea trainedpbilologist.

The Indo-Chinese Ia.nguages also continued to receive study. The indefatigable Indo-Ott. ........ Lan,auagea. Logan published euay after ellsa.y in the" Journal of the Lopn Indian Archipelago," in which the languages of Burma. and A.JJsa.m were compared and a.na.lysed.

Logan wanted the philological tra-ining possessed by Caldwell, tmd hence his work has not retained the a&me authority M that of t he great bishop, but he made many shrewd suggestions as to the relationship existing between the languages with wh ich he d.6alt , a.nd these have been confirmed, or rediscovel-OO (for his writings a.re hardly known at the present day), by subsequent inquiret"ll. •PorOOs's posthumous 'Compamtive Grammar of the Languages of F:tuther India' (1881) is but 8. tantalizing fragment, and it fell to the I.ate prof6880r Ernst Kuhn to att.ack seriously one branch of the question and. to put t he philology .... r tile languages of Further India upon a sound footing. His B ritrage zur Spt'achenkmukHinUriHdietu in the ' Silizu.ngsberichte• of the Royal Bavarian Academy of Sciences (1889) has baen the ~rting point for a number of, younger studon.ts ~ho are writing at the p resent day, amongst whom special attention must he drawn to Pater AIUtro-Aalatfu.A1UItrlo. W. Schmid.t'shrilliant work on 'Die Mon-Khmer-Volker' (1906). Ptl.t6r .schmidt has here proved not only t hat the Mou~Khmer languugos form flo link between the M~4i languages of India proper and tho l&ngua.ges of Indonesia, ---grouping the first two; with Khasi and some other minor forms of speech.

under the one name of the' Austroasia.tic' languages.-bui; has gone much further. He has shown that the languages ofIndonesi&, Melanesia, and Polynesia also (orm•a group which he terms the' Austronesic.' The IndOJle8lan languages thus form & link between the AustTOOsiatic and the Austronesic Ia.nguages, the whole forming one groo.t linguiBtic rn.mily,-caJ.led the'Auatric'-extending from the bills of CentmlIndiato Ea.sterIsland,off thecoost of South America, and covering a wider dorea even than that of the Il;do-European tongues. Indo-Aryan languages also received attention in the Bengal Asiatic Society. The

us, though mention must be made of the wonderful pioneer work done in this direction by Ma.jor Robert Leech. We owe to his indefatigablediligence and accurate observation quite an extraordinary number of vocabularies and grammars of• hitherto untouched. Iauguages. Between 1838 a.nd 1843 he ga.ve us gmmma.rs of Brahlil, Bal.Oebi, PaiIjibi, Palli}to, Bund6li and Kashmiri, besides vooabula.ries of Ormnp, Pashai, Laghmini, KhOwir, TiI•ahi, and Diri. For some of those hiB work is still our only authority, for the IB.nguages lire now either extinct or spoken in tmcts not since visited by British officers. For others, his work was superseded only at the end of the nineteenth century.

It was in Bombay that the comparative study of the Indo-Aryan languages W88 resumed thirty-seven years after the publication of Carey's Report. We find tbe evidence of this in the fourth volume of the J ournal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. In the number for January 1853 Sir ThoD'UUI E rskine Peny, then ChiefJnsticeof Bombay and President of the Society, published his paper' On the Geographical Distribution of the principa.l Languages of India.' He divided the langua."noes of India. iuto two great cl.asses,- 'the 1u.nguage of the intruding Arians, or Banskritoid', in t he North, and the language of '" civilizOO. race in the South of lndm, represented by its most cultivated branch, the 'l'amil.' The fonner he reckoned 811 seven in number, ole., Hindi, Kashmiri, Bengali, Gujariti, Mari.~hi, Koilkaq.i, and Oriy'" with ten dialects. PanjAbi, Lahndi. (called by him MnltAni), Sindhi. snd llirw4rl he looked upon as all diaJecta of Hindi. MaitbiU he classed S8 So dialect of Bengali. Since he wrote, it will be soon that many of the forms of speech that he looked upon as dialects have been raised to the dignity of being rec0gnized as independent languages.

Tbe &uthet>n Iangua.ges he called • Twaniau or Thmiloid.' He did not 800m to-be aware of• the term -. Dravidian' which was first used simultaneously in 1856 both by Hodgson and by Caldwell. Perry mention~ Telugu, Ka.na.rese~ Tamil, Ma.layilam, Tulu, Md (with 1.10 query) G01.l4i. He gavo brief- descriptive accounts. of the geneml charactmistics of each wl~ae, and carefully indico.ted the habitat of each, the whole being illustrated by an excellent language map. It will be observed tha.t be altogether ignored the Indo-Chinese languages, and that be made no mention of the

- Munda. lan~, which w~re not identified hy Max Milller till the following year.

While Perry confined himseU to the geogmpbical distribution of the Indian languages, another Bomoo.y scholar Was studying the interal'tion between Indo-Ary8oD. and Dmvidian langoages. The same volume of the Journal of the Bombay Branch of the R. A. S.

contains J. Stevenson's Oompan:dioe lTocaIJulary of the B~

SatUlCf'i.t VOC4bles of the Vernacular Languages of If/du..

Rere the important question of the borrowing of Dravidian wo~ by the different Itido~

Aryan laligua",~ &udof its ethnicalsignifiea.nce is treated. for the first time, and with gl-eat

ucumen. ,It was iuevifable that, at that stage of linguistic science, many of Stevenson's

comparisons should be mista.ken, hnt, ijtill the article reoiains a solid contribution to the

geneml .linguistic science of India..

On the other side of India, in IB67, John Bea.mes, a yOWlg Indian Civilian of barely

ten years' service, attl1l.Cted attention by the publication of a.

little summary of what was then known about all the lang•

~ of the country in his "Outlines of Indian Philology.' .Five y6l.l>rs later: appeared the

first volume of his well-known' 'Comparative.GrammlU• of the Aryan Lau,guages of

-India.' The sa.me year witnessed the publication of Dr.

Roornle's first essa.ys in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal on the same subject, which were followed in 181:0 by his • Grammar of Eastem Hindi compared with t he other Gau<J,rn.n Languages.' These two excellent works, each a masterpiece in its own way, have since been the twin foundation of all researches into the origin and 'mutual relationship of, the lan~aes of the Indo-Aryan family of speech All this time, for many decades, grammars and vocabularies of individual fOl'ms of Indian speech had. been issuing in considerable numbers. For the better known ltmguages, such as HindustAni, Mari.thi, or Benga.li, they came out in scores, and it must be coufessed that most of them wel'C but bbou r wasted.

Each writer copied his predecessor, according to his capa.city, corrected a few mistakes or not, introduced a. few more or not, alld proclaim.ed a new gospel which was not -new. Now and then a. work of striking merit, i\uch as Molesworth's Marathi Dicti01lll!ry, Trumpp's Silldhi or Kellogg's Hindi Grammar, appeared, but most of the rest were sorry stuff and were hardly wanted. The less-known lauguages, though equally important, were studiously left alone. Carey wrote his Pafijabi grammar in 1812, and, except for a brief sketch by Leeeh~ it was forty years before anyone again attempted to describe in a. formal manner t he language of the Sikkhs, But, if this was the cas.e with languages' whose speakers were numbered by millions, the sta.te of affairs regarding the scores of minor languages spoken by thousands, the languages of the hill-t ribes of Centml India, of the Tibeto-Burmans of Eastern Bengal and Assam, was much worse. An enthusiast wrote a grammar or compiled a vocabubry here and there. Government ~lICOUraged its officers to make more, and a few did BO,-excellent works in their way.

In 1874, Sir George Campbell, then Lie.l1tenant-Governor of Bengal, Pl°inted a set of vocabularies compiled by local officials, but, with this exception, very little was done, Even with the help of foreigners the work ha.rdly progr-essed. The first serious grammar of Pa.t;.bto,-the language of Buulall in.,.eltlgatlous. Afghanistan,-was written by a R\tssia.n-Dorn-and 'up to quite lately, although nnmerous elementary grammars have boon written by Englishmen, all the scientific study of this form of speech was carried On by French or Germans. Similarly, we owe the only existing gmmmar and vocabulary of Newiri, the plincipal language of Nepal, to another Russian.

Examples of t his kind might be multiplied. hut. even with outside help, the tota l result W88 that our knowledge of these minor lang1l&o<>e8, It knowledge most important for the purposes of administmtion l:loS welt '8& in the interests of science, was scanty, unevenly distributed, and UIlcqual. In fact, so late as the year 1878 no one had as yet made even a cata.logue .:of aU the languages spoken in India., and the estimates of their number varied. between 50 or 60 and 250. Dr. Oust made a bra.ve attempt to put together such an inventory in that year, but his" Modern Languages of the East Indies" in spite of all the industriolllill learning and &.Cumen of its author, was confessedly a compilation of existing materials, and these materials were equally confessedly imperfect. It was a tentative work, and was primarily inteuded to stimulate enquiry, not to close the subject.

Dr. Cust's work succeeded. It did stimulate enquiry. For the first time Government, as well as Ellropean schola.rs, were enabled. to see what little had been done aud how milch remained to be done. People talked. about it and wrote about it. It was Vlen.na Cong ....... ouess. finally diBcussed at the Orienta~ Conguss held at Vienna in 1886, of which Dr. Oust was himself a. member; and the assembled scholars passed a resolution urging upon the Government of India to undertake' a delibemte systematic survey of the Ia.ugua",<P68 of India. n The proposal was favourably received, but the adoption of a detailed scheme was delayed. at first on financial grounds. In the year 1894 the matter came within the region of practical politics, and the prelimi.nary details came under discussion. The first question to be settled. wtu!

Provinces of Madras and Burma and the States of Hyderabad and Mysore from its operations, so that these would cover, from the West to the East, Baluchistan, the NorthWest Frontier, Kashmir, the Punjab, the Bombay Presidency, Rajputana and Central India, tbe Central Provinces and Berar, the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, Bihar .and Orissa, Bengal, and Assam, • then containing a popUlation of about 224,000,000 Ollt of tho 294,000,000 of our Indian Empire Tben, 80S to the nature of the Survey.

After some disclllilsion it was decided tbat it was primarily to be a collection of specimens, a standard passage was to be selected for purposes of comparison, and t his was to he transla.ted into every known dialect and sub-dialect spoken in the area covered by the operations. As this specimen would necessarily be in every case a translaioll and would, therefore, run the risk of being unidiomatic, a second specimen was also to be called for in each case, not a translation, but a piece of folklol•e or some other passa.",<>e in narrative prose or versl:l, selected UIl the spot and ta.ken down from the moutb of Ihe speaker.

Subsequently a third specimen was added . to the scheme- a standard li.lt of word and test sentences originally drawn up for the Bengal Asiatic Society in 18661 by Sir George Campbell a.nd already widely used. in India. It was obviously desirable that, for purposes of comparison, this. list should be retained in its entirety, and 80 it was done, but a few extra. words were added. The foundation of the Survey is thus these three speeimens;-thestandard translation, the passage loca.llyselected, and thelistof words and sentences. It was then determined that; the first specimen should be a version

of the Parable of the Prodigal Son, with slight verbal alteration to avoid Indian PI~judices, a. JlIlS8f'g'O which luw been previous!,. Wted tuld is admirably suited (or sucb pur- -.' This h&ving been dooided. I WltlJ entrusted with the task of collecting the specimens Rnd of editing them for the presti. With this object, the varioU6 local officer6 were infltruCted to render me the necessary ltIJsistance, and [ should be ungrateful (lid I uot cordially cxpress my gratitude for the sy.mpathetic and Wlgmdging help accorded by my brethren in the service of the Indian Governments and by many othcr6, EurOpeallS and Indi&ns,missioJl8lries&ndlAymen. Before getting the specimens, we had to find out what it was tha.t we WWlted spooi-

under survey. Forms were BOut out to ea.ch district officer and political agellt with 8. request tha.t he would fill in •the I16me of every langwige spoken in his chtt.rge, together with the estimated number of speakers of ee.ch. The fonns came b6.ck by degrees, and. their contents, I inust confess, rathel• appo.lled me. The total number of languages reported from the •survey a.rea WM 231 and of dialoots 774. Examination fortwlu.tely abowed that some few namCII were returned over and over again from different provincC6, and also that it W&II probable tha.t in many CIl.SeS the same form of speech W8B reported under different names.

I may say that, now that the process of elimination has been completed, the number of laogun.ges spoken in that portion of the Indian Empire subjected to the Survey amounta to 179, a.nd. the nnmber of di.a.lecta to 544, all of which u.re descrilled in tJ..tese volumes. For the whole Indian Empire, the Census of 1921 give.. 188 langua.,<>ea, • the total number of di.a.lects being unknown. 'I'he preparation of these lists was no easy moohanica.l process,- the sort of thing t ba.tcouldbedoneby aninteUigent clerk. I pass over the difficulties encountered in

hundreds of returns from different sources will know its laborious character, und those who have not can imagine it. But great difficulty wa.s often ex.perienced in prop~ riDg the local returns that formed the materials on which I had to work. Each officer k.n ew IIIobout the Dl3in language of his district, and, if he had been there some time, btld probably a working acqusinb\oce with it. But over and over again no one with any educlIIotioli knew a.nything about the little hole-in-the-oorner fo rms of speech which were discovered &II soon 8B search was instituted. Let me give• one example. In one of the Himalayan districts. of which the main language W8.II Arya n, a small colony was diaIlOVt:;\ red which originally hailed. from Tibet, and which retained its own language.

No o fficml kuew it, .and intercourse with them was conducted t hrough the medium of a. I ingua franca. The district officer en~red the name of t his language in his return. This ll8.llle W&II not Olle word, or two words. It was & solemn procession of weird mOllosy lla. bles wandering right a.croes &. }l&.,"'6. I could make nothing of it, oor could my Tibetanknowing

friends. It should be remembered tlut.t; it was & foreign expression written down in English let~rs as it sounded to the untrained. ear of a person entirely untItOquainted with it. All my endeo.vours to identify the name failed. At 1a.at I wrote to the distriot officer and asked bim to make further inquiries. In reply it was expla.ined tba.t investigation had. shown that the mOIlO6yUabio procession was not the name of any la.ngullo"'C, but W811 thc local method. of expressing in broken Tibetan' I don't understand what you are driving a.t.'

Another difficulty was the finding of thc local name of a dialect. J WIt as ~{. ~l LLD&uage•nomenat&ture. ~~:~~ so~~en:!e~:; I:t.;!nh:i~~:: s!~::!\:;:~! has boon speakiug anything with a name attached to it. He can always put a. name to the dialect spoken by somebody nfty miles off, but, - as for his own dialect,- ' 0, that bas no name. It is simply correct language.' It thus happens tha.t most dialect names a.re not those given by the speakers, but th066 given by their neighbours, and are not always complimentary. For instance, there is a. well-knowll form of speech iu the south ofthePunjabcalled.'Jangali,'from its being spoken in the 'Jungle,' or uninigated country bordering on B ikaner. But' JQngali, ' also moolls 'boorish' all(l local inqlLiries failed to find a single person 'who "dmitted that he spoke that langlUlb"C. • 0 yes, we know J angali very well,- you will find it a little further on,- not here.' You go a little fnrther on and get the same reply, and pursue .roar ",iIloO'-the-wisp till he hnds you in the Rajplltaua. desert. where there is no one to speak any lnngua!.~ at all. '.rlu~e ilIustmtions show the difficultieseucountered by local offiOOl1lin identifying dialects and naming t hem.

Fromthe loco.l listsreceived,asdescribedabove, provincial lists wel'C compiledanll printed. These did not profess to be accurate catalogues of the tongues of India. They claimed only to represent the then existitlg knowledge or the state of affuirs as reported by olllcen! witilloca.l experience, who did not pretend t.() be philolog ical expe'is. As snch, they formed the basis of the Snrvey operations . . When the lists were printed, the dialects were divided into twoma.irlclasses,distingnishedbya difference of type, viz., (l) those which were vernaculars of the localities from which they were reported, and (2) those wbich were spoken by fore igners ill each locality. The latter were once for nil- excluded, and atte,\tion was thenceforth devoted only to the former Each district officer was uow &8ked to provide a set of the three specimens of each Collectl.OD ot.peoillIea.. language locally vernacuht.r in his district. Careful in.struotions were given for the preparation of these specimens.

It will be remembered that the first was to be a. trnnsla.tion of the Parable of the Prodigal Son. It WM recognized that in many, nay, in m08t cases, the t ranslators would llot know English, and in order to l;ll>Sist them a volume of a ll the k nown versions of the pamble in Indian languages was compiled 'with the help of the British and Foreign Bible Society, of local missionaries, and of oue or two Government officers who were speciaJly interested in the Survol' This collectioq, which was published in 1897, under tile name of 'Sper:imen Translations in variomIndia.nlangua.ges,'oontAinedsixty-fivc versiollB. and, though prima.rily intended. as 8. tool to aid the execution of the sche:ne, aroused some temporary interest a.mong the dolars of Europe. For the ~urvey, i.t Wll~ anticipated that whoever might have to prepare a specimen, even if he did not know English, would find in this hook at 1688t one version from which he could mal..tl a tnmsla.tion ; and. this. in fact, was bOrne out by subsequent experience.

The'second specimen, which was to be locrilly selected, pl"e8euted. no simil.a.r difficult. iea, but inst.nroti.ons were given that all specimens were to be wrilten (CI) in .. the ve.rnacular character (if there was one) and (b) in the Roman character with a. word for word interlinear tranala.tion. The seoond specimen was also to be furnished. with a froo translation into good English. As to the style of translation into the vernacular, local officers were told that the language of literature was always to be avoided. What was to be &imed at was the acquisition of specimens in the home language of each translator. whether it was looked upon 88 vulgar patois or not: For the third specimen, the standanl list of words and sentences, blank books of forma were suppliec:l, which needed. only to be filled up.

As each provincial list of langt.tages was completed, the circulars calling [or specimens were issued.. 'I'be latter began to arrive in 1897. and moat of tbem were received by the end of 1900. though a. few belated. IllpecimeDS continued. to come at irregular intervals during the snooeed.ing yean. The editing and collating of the specimens began in 1898. The first rough work W88 done in India, but in 1899 I rel;urned to EIlgland, where for some years I had the efficient aid of my Assista.nt Dr .• now Prof68lJOr, Konowof Christiania.

The editing of the lllpecimens has been an interestmg work. but it involved BOrne BdJ.ttq of the .peolm..... unexpected difficulti6ll. Before anything could be printed. a general scheme of classification had. to be decided upon, Mld that on a very imperfect knowledge of the materials. As t he work went on disoover~ea . were made which rendered revisions of the Cl&asificatiOll necessary; and sometimes these were made too late, 80 that the materials ha.ve not a.lways been arranged as. with further knowledge, I should like them to be a rranged now.

This was especia.lly the case in regard to the Indo-Chinese languages, in which my Assistant and myself were often walkulg on ground which' hitherto had. boou uutrodden, aud had to deal with languages for which no gra.nuna.rs or diotionaries existed. Rere mistakes in cla.ssificatiOll were inevitable; but I am glad that I C&Il think that 1l0lle of first class importan~ were made. and that., on the whole, though I might now group a. few indi vidual differently from the lD&IlIler in ,,:hich they have been grouped in the published volumes of the Survey, my present knowledge would not lead. me to make auy lIIubstantial a lterntiOll.

I ba.ve never counted the total number of specimens received. They amount to several thousands, and it stands to reason tha.t it was not possible to print them &11. The . surpluso.ge W&8 deliberately estimated for. It was calcul~ that t he specimens would vary iii value. Several would be received of each dialect. Some would be prepared carefully. others ignorantly. others carelessly. Many of them ;vould Come from the mouths of uneducated people, hardly able to gn:u;p the idea of what. was required.

A mass from which •to select was therefore a. desideratum, and t his. in most cases. was secured It is only in the case of a few 1e88-~nown dialecte of the Himalaya and of the Ass&m frontier that lIIingle specimens were obtained. These were. in all eaeea. fonus of lllpeech which had never been. recorded. in writing before, and mistakes in recording them were to w expecWd. 'I'hanks to the eonJ;tant sympathy and ungrudging aid given by OUl" frontier offiooN,-the most enthusiastic among my helpers;- many doubtful points were cleared. up by correspond.enoo, and I hope that in after yean; it will be found that these specimens are not very wrong. Absolutely accurate w& cannot expect them to be. To give an example of the difficulties experienced. I may mention that the corrootion of one spooimen was dela.yed for over six months by a. faJ.1 of snow in the Hindilkush.

which prevented the Politica.l Agent Bot Chitral obtaining the semcea of the only getat&ble bilingual speaker of one of the Pi.mir dia.lects. Again. in the C880 of one of the Kifir languages or the Hindukush. no one who spoke it could at first be got hold of. At lellgth, a.fter a long search, a shepherd of the desired nationality W88 enticed from his native fastness to Chitral. He was exceptionally stupid. probably very much frightened, aud knew only his native language. A Bashgal Shekh was found who knew a little of it, and who a lso knew Chitrili, with his aid the tm.nslation of the Parable was IIl.I:\de through Bashgaliand Chitrili. Much accuracy could not be expected from the result; but" with care and the tlS8istAuce of the local offiners, a. version was ultimately made, which, though it contained some JlR8Iil'8C8 that I have been unable to all&lyae completely, has very satis£actorily complied with the somewhat stringent philological testa to which it h&8 boon subjected.

I'his was by no means an isolated example. 'I'here were scores of 1a.llg~ for which no one could be found who knew anyone of them and at the lIame time English. It might be thought, for ins~nce, that our officials would be familiar with most of the laugua.gee spoken in the neighbourhood of the port of Chlttagong. Yet there is au iu.si:anoo on record of a c rimin&l C&86 which was tried in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. One of the witnesses was a woman who knew only the Khami la.nguagc. This was translated into Mra, which was then translated into Arakanese, which was 8.o"&in translated into the local dialect of Bengali, from which version the It:agistrate recorded the qww.ruply refracted evidence in English. This makes no reflection on the officer conoorned. There are pArts of India which 806m to have had. each a special Tower of Babel of ita own. l!'rom the little Province of A8Sa.lll, with its population of _only about six Il-lld 8. half millions, - or a. million less than that of Loudoll,- eighty-oue Indian. Jaugtmges were returned at the Census of 1911, aud it CQnta.inal others that were not 8pooifica.lly returned. Mezzofunti hirolfOlf, who spoke fifty.-eight languages, would have boon puzzled here.

As each dialect Wllo8 examined, a specimen or spooimellB of it were so lected for publication a.nd made ready for the press. From the specimens a sketch of the grammatical and other peculiarities was prepared, and ",Cerence was made to any point worth noting about the speakers. Dialects were theu grouped into languages, and for each language 8. somewhat elaborate introduction was provided, sketching the habitat aud number of speakers; distinguishing the dialects !Lud comparing their charnctcrilltic8 ; giving, when known, tho ancient history of the language, and dellning its rolationship to other members of the same family; describing briedy the lIalient point.'l (If the litera~ ture, when there was one; supplying a bibliography as full as we were a.ble to make it; and concluding with & sketeh of the grammar. The results are to be found in Lhe volumes of the Survey. to which this is an Introductiou.

Throughout the whole series of opera.tions, one thing has boon steadily borne inlD80me order or other, and this necessitated grouping, a.nd grouping nece&8ita.ted the adoption •of theories as to relationf;hip.t So much could not be helped; but beyond this every efJ'orthas been made to preveut the Survey becoming an encycloprodia of Indian philological scicnce. 'l.ihat will. we may hope. follow when scholars more competent than the present writer ha.ve had time to digest the immense mass of ordered facts now placed at their . disposal. Indeed, a beginning hasalrea.dy been made.

Referencchas already been made to Pater Schmidt's discoveries regarding the Austric languages, and it. has been a legitimate IIOUrce of gratifi~tion to me to observe the froo use of the Survey which' has heen made by Monsieur Jules Bloch in his researches into llaritlii, by Professor Turner and Professor Buniti Kumar Chatterji in their important studies in GujartiU and Eengali, and by Dr. Paul Tedesco in his luminous essays on the history of Aryan languages. • One interesting result of Pater Schmidt's inquiries may here be added, as it has a. directconnexion with the Survey.

The MUI)qala.ugll8.ges, as we know, belong to Chota Nagpur and the centre of India. It is also a w.miliar fact that the languages spoken in the Himala.ya, far to the north of these }fUl;Jqii. la.ug~o-es, are Tibcto-Burmall in clw.mcter. But eveu here the Survey shows us that there is a line of peeulitu• forms of speech, extending from Darjiling to the Panjab, that show evident trnces ofapreviously existing lallguage of the lIuQQ8, family, which has been overlaid, ~o to speak , by the Tibeto-Burman of the la.ter immigmnts.

There is thus evidence to s how the existence, at some very ancient time, of a common language of which traces are still visible from Ktlnawar in the Panjab down t.hl"Ough Further lndhl and ".cross the Pacific Ocean ItS far as Easter Island and New Zealand. Philology is 110t to be .confolWdcd with Ethnology, and here we may leave these interesting facts in the hands of ethnologists for furlhet• cKamination.

In the course of the Survey. it has sometinles been difficult to decide where a given 'Language'and'dlr.leot' • ~~:~,O!r ~7!ali:C~0i:o~k:;h~~0;e~uia: i;;~:e:;les~!:~- In practice it has been foun(1 that it is sometimes impossible to decide the question in a manner which will gain universal acceptance. The two words' language' and ' dialect' are. in this respect, like' monntain' and' hill.' One has no hesit.ation in sayillg that, •.Uy, Everest is a mountain, and Holborn Hill, a. hill, but between these two the dividing line cannot be accurately drawn. Moreover we often talk of the' Darjiling Hills' which are over 7,500 feet high, while everyone calls Snowdon, with its poor 3,500 feet, 's mOUllwin. 'Language' and 'dialect' are often used in the su.me loose way.

I n common use we may say that. as a geneml rule, different dialects of the same language aresufficientiy alike to be reasonably well understood by alt.whose native tonglle is that IMlgmtge, whilediJIerent languages are so Ulllike that special study is needed to ellable one to lmderstand a language that is not his own. 'l.'hig is the explanation of the Century Dictionary,~ but the writer adds that 'this is not an essential difference.' and nowhere isthis proviso more needed than in considering the Aryan languages of Northern India. There, mutual intelligibility cannot a lways be the deciding factor, for the consideration is obscured by the fa.ct that between Benga.l and the Panjab every individual

who has IOOeived the very slightest education is bilingua.l. In his own home, I\nd ill his

own immediate surroundings he speaks a local idiom, but in his intercourse with

stmn",<>ers he employs or understands some form of tlut.t grea.t lingua. frauca.,-Hindi or

HindOst!.ni.. Moreover, over the whole of this vast &n»,-including even Rajputana,

Central India., a.ud Guja.rat,-the great mass of the vocabnla.ry, including ncarly &Il the

words in common use. is. a.llowing for v&rio.tions of pronunciation, the SAme. It is thus

cominonly said. and believed. that throughout the Gtmgetic V&lley. hetween Bengal

u.nd the Panju.b, there is one language. aud one only, Hindi. with numerous loca.l dialects

From one point of view this is correct, and e&nnot be denied. Hindi or RindUswni is

everywhere the ll\llguage of administration, and is the one medium of instruction in the

rumiscboolti. The people, as I wwesaid, being biJ.ingtu.i,littieornoinconvenienoo is

caused in practice by the employment of the ll88umption, a.nd no one in their senses

would wish to complicate administration by the introduotion of a. confusion of tongues.

And yet, when these numerous 8O-C&1led dialool:.e of this' Hindi' are examined by the philologist, a.nd when he attempts to group and classify, he is at once confronted by ra.dical differences of idiom and construction. Some of these dialects are as nna.lytie&J as English.-othel'8 &re 80S synthetic as German. Some htloVe the simplest grnmma.r, with everyword•rolationshipindicated, not by declension or conjugation, but by the use of help-words; while others have gramma.I"8 more complicated tJum that of wtin, with verbs that change their forms not only in agreement with the subject. but even with the object.

To look upon 11011 these a.s dialecj;s of " single Ia.nguage is as phitologie&lly impossible, us it would be, say. to describe Germa.n M u. dia.lect. of English ; and helice, in the Linguistic Survey, they Mve been sorted out. llccording to their grnmmatical systems. into three groups. each of which is given the-dignity of a lauglUl{;6,- Bihari. Eastern Hindi, and Western Hindi. This division has not escaped criticism. For instance the writer of the Report on the Census of the United Provinces [or 1921 88.ys' that • the difference bet.ween speaking to a villager of Gora.khpllr [where the ia.ngna..:.o-e is Bihari] and to a jungleman of Jhansi [where the la.nguage is Western Hindi] is precisely the difference hetwcen speaking to a peasant. of Devon a.nd to a crofter of Aberdeen. If you are intelligible to the one you cu.n with }Utience Il'lUke yourself intelligible to t.he otber.' I myself ha.ve never had. an opportun~ty of pel'8Oll!\lly compariug the dialects of Devon and of Aberdeen, bnt I would 5u",<rgest that the true point of difference has been here missed. The question U! not whether an educated third person can master the two dialects, but whether & Devon pea.sant suddeuly transported to Aberdeeu would be a.ble to communicate with the surrounding crofters. . I [ea.r that a considemble amount of patielll:e would ha.ve to be exercised in such & case before interoommunication could be e8tablished. and even then it would be helped out by idioms borrowed from the Ia.nguage of Uucle Toby's Army in Fla.nders.

'l'his brings WI back to the proviso stated. by the writer in tke Century Dictiona.ry. to which I have a.lready drawn attention. The ditIerentla.tion of & langua.,ao doea not Ilec.::ess&rily depend on non•intercommunicability with another form of spooch. There a.re o.lso oth.cr powerfnl factors to be considered. if we are to look at the subject from a lICientific point of view. First a.nd fommost. there is what I have already l-eferred to,gr& mmatic&l st~ctnre. Our peasant of Gomkhpur mayor may not be intelligible 'ltepon.Ch&pterIX,§'.

to the junglema.!l of Jhausi, but that does not do away with the fact that his language is highly synthetic. with & verb the conjugation of which is more ooropl icakd than that of Latin. The Jh.ansi jungleman, on the contra.ry U8C8 8. tongue with hanily any synthetic grammar at all. HiB verb has but one real tense, and two part.iciples. All the other relations of time nre indicnted by the combination of these participles with help-words. The vocabulary of the two fonns of speech may be very 8iooi l&r, but the whole grammatical structure of the one is radically diJferent from that of the other. It i8 impoSsible, from the point of view of science, to group them together as dialects of a common language.

'l'here i8 another factor which exercises influence in thi8 differentiation. Iti8 natior.ality. It is 8tLid that; some Engliah peasa.nta would ill Holland find little difficulty in making themselves undenitood. or in understanding what people ~y. Yet no one would deny that Dutch and English are distinct languages; and this factor ' is all the stronger when each nationality has €!eveloped an independent literature. There is an excellent illustration of this in ABS8.mc8e. Thi8 form of spooch is now admitted. to be an independent language.-yet if merely ita gr&mmatical form and its vocabulary are ooll8idered.. it would not be denied that it is a dialect of Bengali.

It is certainly as closely related in these respects to the sta.ndard form of that language as is the dialect of Bengali spokcn in Chittagong. Yet ita claim to be considered as an independent language i8 incontestable. Not only is it the Apeech of an independent nation. with a history of its own. but it has & fine literature differing from that of Bungal both in its standa.rd of speech, a.nd in its natwoe and content. Here. therefore. we bl\.ve an example of a language differentia.ted from its neighbours not by mutual .un.intdligibili.t.y but by nationlLlity and literature.