Kurmi

Contents |

See also

Members of the community may kindly advise us if one or more of the belowmentioned pages can be merged with another page. This information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook

community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully

acknowledged in your name.

Kurmi

A 1916 account

This section was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Kurmi

In 1911 i the Kurmis numbered about 300,000 persons in the Central Provinces, of whom half belonged to the Chhattlsgarh Division and a third to the Jubbulpore Division ; the Districts in which they were most numerous being Saugor, Damoh, Jubbulpore, Hoshangabad, Raipur, Bilaspur and Drug. The name is considered to be derived from the Sanskrit krishi, cultivation, or from kunna, the tortoise incarnation of Vishnu, whether because it is the totem of the caste or because, as suggested by one writer, the Kurmi supports the population of India as the tortoise supports the earth.

It is true that many Kurmis say they belong to the Kashyap gotra, Kashyap being the name of a Rishi, which seems to have been derived from kachJiap, the tortoise ; but many other castes also say they belong to the Kashyap gotra or worship the tortoise, and if this has any connection with the name of the caste it is probable that the caste-name suggested the go^ra-name and not the reverse. It is highly improbable that a large occu- pational caste should be named after an animal, and the metaphorical similitude can safely be rejected. The name seems therefore either to come from krisJii, cultivation, or from some other unknown source.

Functionai char acter

There seems little reason to doubt that the Kurmis, like ^j^^ Kunbis, are a functional caste. In Bihar they show of the ' _ ' ^ caste. traces of Aryan blood, and are a fine-looking race. But in Chota Nagpur Sir H. Risley states : " Short, sturdy and of very dark complexion, the Kurmis closely resemble in feature the Dravidian tribes around them.

It is difficult to distinguish a Kurmi from a Bhumij or Santal, and the Santals will take cooked food from them." ^ In the Central Provinces they are fairly dark in complexion and of moderate height, and no doubt of very mixed blood. Where the Kurmis and Kunbis meet the castes sometimes amalgamate, and there is little doubt that various groups of Kurmis settling in the Maratha country have become Kunbis, and Kunbis migrating to northern India have become Kurmis. Each caste has certain subdivisions whose names belong to the other. It has been seen in the article on Kunbi that this caste is of very diverse origin, having assimilated large bodies of persons 1 'J'rihes and Castes 0/ Bengal, a.x\.. Kurmi.

/from several other castes, and is probably to a considerable fextent recruited from the local non-Aryan tribes ; if then the iKurmis mix so readily with the Kunbis,the presumption is that rthey are of a similar mixed origin, as otherwise they should jconsider themselves superior. Mr. Crooke gives several names of subcastes showing the diverse constitution of the Kurmis. Thus three, Gaharwar, Jadon and Chandel are the names of Rajput clans ; the Kori subcaste must be a branch of the low weaver caste of that name ; and in the Central Provinces the names of such subcastes as the Agaria or iron-workers, the Lonhare or salt-refiners, and the Khaira or catechu-collectors indicate that these Kurmis are derived from low Hindu castes or the aboriginal tribes.

The caste has a large number of subdivisions. The 3- Sub- Usrete belonged to Bundelkhand, where this name is found in several castes ; they are also known as Havelia, because

they live in the rich level tract of the Jubbulpore Haveli, covered like a chessboard with large embanked wheat-fields. The name Haveli seems to have signified a palace or head-

quarters of a ruler, and hence was applied to the tract surrounding it, which was usually of special fertility, and

provided for the maintenance of the chief's establishment and household troops. Thus in Jubbulpore, Mandla and Betul we find the forts of the old Gond rulers dominating an expanse of rich plain -country.

The Usrete Kurmis abstain from meat and liquor, and may be considered as one of the highest subcastes. Their name may be derived from a-sreshtha, or not the best, and its significance would be that formerly they were considered to be of mixed origin, like most castes in Bundelkhand. The group of Sreshtha or best-born Kurmis has now, however, died out if it ever existed, and the Usretes have succeeded in establishing themselves in its place.

The Chandnahes of Jubbulpore or Chandnahus of Chhattlsgarh are another large subdivision. The name may be derived from the village Chandnoha in Bundelkhand, but the Chandnahus of Chhattlsgarh say that three or four centuries ago a Rajput general of the Raja of Ratanpur had been so successful in war that the king allowed him to appear in Durbar in his uniform with his forehead marked with sandalwood, as a special honour.

When he died his son continued to do the same, and on the king's attention being drawn to it he forbade him. But the son did not obey, and hence the king ordered the sandalwood to be rubbed from his forehead in open Durbar. But when this was done the mark miraculously reappeared through the agency of the goddess Devi, whose favourite he was. Three times the king had the mark rubbed out and three times it came again. So he was allowed to wear it thereafter, and was called Chandan Singh from chandan, sandalwood ; and his descendants are the Chandnahu Kurmis. Another derivation is from Chandra, the moon. In Jubbul- pore these Chandnahes sometimes kill a pig under the palan-

quin of a newly married bride. In Bilaspur they are prosperous and capable cultivators, but are generally reputed to be stingy, and therefore are not very popular. Here they are divided into the Ekbahinyas and Dobahinyas, or those who wear glass bangles on one or both arms respect- ively.

The Chandraha Kurmis of Raipur are probably a branch of the Chandnahus. They sprinkle with water the wood with which they are about to cook their food in order to purify it, and will eat food only in the chauka or sanctified place in the house. At harvest when they must take meals in the fields, one of them prepares a patch of ground, clean- ing and watering it, and there cooks food for them all. The Singrore Kurmis derive their name from Singror, a place near Allahabad. Singror is said to have once been a very important town, and the Lodhis and other castes have subdivisions of this name. The Desha Kurmis are a group of the Mungeli tahsll of Bilaspur. Desh means one's native country, but in this case the name probably refers to Bundel- khand. Mr. Gordon states ^ that they do not rear poultry and avoid residing in villages in which their neighbours keep poultry. The Santore Kurmis are a group found in several Districts, who grow ja^-hemp,^ and are hence looked down upon by the remainder of the caste. In Raipur the Manwa Kurmis will also do this ; Mana is a word sometimes applied to a loom, and the Manwa Kurmis may be so called because they grow hemp and weave sacking from the fibres.

The ' Indian Folk Tales, p. 8. Lorha for a discussion of the Hindus' 2 Crolalaria juncea. See article on prejudice against tiiis crop.

Pdtaria are an inferior group in Bilaspur, who are similarly despised because they grow hemp and will take their food in the fields in patris or leaf-plates. The Gohbaiyan are considered to be an illegitimate group ; the name is said to signify ' holding the arm.' The Bahargaiyan, or ' those who live outside the town,' are another subcaste to which, children born out of wedlock are relegated. The Palkiha subcaste of jubbulpore are said to be so named because their ancestors were in the service of a certain Raja and spread his bedding for him ; hence they are somewhat looked down on by the others. The name may really be derived from palal, a kind of vegetable, and they may originally have been despised for gi-owing this vegetable, and thus placing themselves on a level with the gardening castes.

The Masuria take their name from the niasnr or lentil, a common cold-weather crop in the northern Districts, which is, however, grown by all Kurmis and other cultivators ; and the Agaria or iron-workers, the Kharia or catechu-makers, and the Lonhare or salt-makers, have already been mentioned. There' are also numerous local or territorial subcastes, as the Chaurasia or those living in a Chaurasi ^ estate of eighty -four villages, the Pardeshi or foreigners, the Bundelkhandi or those who came from Bundelkhand, the Kanaujias from Oudh, the Gaur from northern India, and the Marathe and Telenge or Marathas and Telugus ; these are probably Kunbis who have been taken into the. caste. The Gabel are a small subcaste in Sakti State, who now prefer to drop the name Kurmi and call themselves simply Gabel. The reason apparently is that the other Kurmis about them sow j'«/z-hemp, and as they have ceased doing this they try to separate themselves and rank above the rest. But they call the bastard group of their community Rakhaut Kurmis, and other people speak of all of them as Gabel Kurmis, so that there is no doubt that they belong to the caste.

It is said that formerly they were pack-carriers, but have now abandoned this calling in favour of cultivation. Each subcaste has a number of exogamous divisions and 4- Exo- 1 • r n r^ 1 ganious these present a large variety of all t)'pes, borne groups have groups. ' There are several Chaurasis, a grant of an estate of this special size being common under native rule.

the names of Brahman saints as Sandil, Bharadvvaj, Kausil and Kashyap ; others are called after Rajput septs, as Chauhan, Rathor, Panwar and Solanki ; other names are of villages, as Khairagarhi from Khairagarh, Pandariha from Pandaria, Bhadaria, and Harkotia from Harkoti ; others are titular, as Sondeha, gold-bodied, Sonkharchi, spender of gold, Bimba Lohir, stick-carrier, Banhpagar, one wearing a thread on the arm, Bhandari, a store-keeper, Kumaria, a potter, and Shikaria, a hunter ; and a large number are totemistic, named after plants, animals or natural objects, as Sadaphal, a fruit ; Kathail from knth or catechu ; Dhorha, from dhor, cattle ; Kansia, the kdns grass ; Karaiya, a frying-pan ; Sarang, a peacock ; Samundha, the ocean ; Sindia, the date- palm tree ; Dudhua from dudh, milk, and so on. Some sections are subdivided ; thus the Tidha section, supposed to be named after a village, is divided into three subsections named Ghurepake, a mound of cowdung, Dwarparke, door- jamb, and Jangi, a warrior, which are themselves exogamous.

Similarly the Chaudhri section, named after the title of the caste headman, is divided into four subsections, two, Majhga- wan and Bamuria, named after villages, and two, Purwa Thok and Pascham Thok, signifying the eastern and western groups. Presumably when sections get so large as to bar the marriage of persons not really related to each other at all, relief is obtained by subdividing them in this manner. A list of the sections of certain subcastes so far as they have been obtained is given at the end of the article. 5. Mar- Marriage is prohibited between members of the same R'Ifroth" "' section and between first and second cousins on the mother's side. But the Chandnahe Kurmis permit the wedding of a brother's daughter to a sister's son. Most Kurmis forbid a man to marry his wife's sister during her lifetime.

The Chhattlsgarh Kurmis have the practice of exchanging girls between two families. There is usually no objection to marriage on account of religious differences within the pale of Hinduism, but the difficulty of a union between a member of a Vaishnava sect who abstains from flesh and liquor, and a partner who does not, is felt and expressed in the following saying : Betrothal,

Vaishnava purtisit avaishna7)a nciri Unt beil ki jot bichdri^ or ' A Vaishnava husband with a non-Vaishnava wife is like a camel yoked with a bullock.' Muliammadans and Christians are not retained in the caste. Girls arc usually wedded between nine and eleven, but well-to-do Kurmis, like other agriculturists, sometimes marry their daughters when only a few months old. The people say that when a Kurmi gets rich he will do three things : marry his daughters very young and with great display, build a fine house, and buy the best bullocks he can afford. The second and third methods of spending his money are very sensible, whatever may be thought of the first. No penalty is imposed for allowing a girl to exceed the age of puberty before marriage. Boys are married between nine and fifteen years, but the tend- ency is towards the postponement of the ceremony. The boy's father goes and asks for a bride and says to the girl's father, ' I have placed my son with you,' that is, given him in adoption ; if the match be acceptable the girl's father replies,

' Yes, I will give my daughter to collect cowdung for you ' ; to which the boy's father responds, ' I will hold her as the apple of my eye.' Then the girl's father sends the barber and the Brahman to the boy's house, carrying a rupee and a cocoanut. The boy's relatives return the visit and perform the ' God bharfm,' or ' Filling the lap of the girl,' They take some sweetmeats, a rupee and a cocoanut, and place them in the girl's lap, this being meant to induce fertility. The ceremony of betrothal succeeds, when the couple are seated together on a wooden plank and touch the feet of the guests and are blessed by them.

The auspi- cious date of the wedding is fixed by the Brahman and intimation is given to the boy's family through the lagan or formal invitation, which is sent on a paper coloured yellow with powdered rice and turmeric. A bride-price is paid, which in the case of well-to-do families may amount to as much as Rs. lOO to Rs. 400. Before the wedding the women of the family go out 6. The •and fetch new earth for making the stoves on which the '"^'J'^g^- '^ sned or marriage feast will be cooked. When about to dig they pavilion, worship the earth by sprinkling water over it and offering

flowers and rice. The marriage-shed is made of the wood of the sdleh tree,^ because this wood is considered to be alive. If a pole of sdleh is cut and planted in the ground it takes root and sprouts, though otherwise the wood is quite useless. The wood of the kekar tree has similar properties and may also be used. The shed is covered with leaves of the mango or jdniun ^ trees, because these trees are evergreen and hence typify perpetual life. The marriage-post in the centre of the shed is called Magrohan or Kham ; the women go and worship it at the carpenter's house ; two pice, a piece of turmeric and an areca-nut are buried below it in the earth and a new thread and a toran or string of mango-leaves is wound round it.

Oil and turmeric are also rubbed on the marriage-post at the same time as on the bride and bridegroom. In Saugor the marriage-post is often a four-sided wooden frame or a pillar with four pieces of wood suspended from it. The larger the marriage- shed is made the greater honour accrues to the host, even though the guests may be insufficient to fill it. In towns it has often to be made in the street and is an obstacle to traffic.

There may be eight or ten posts besides the centre one. 7. The Another preliminary ceremony is the family sacrament marriage- ^^ ^y^^ Meher or marriagc-cakcs. Small balls of wheat-flour are kneaded and fried in an earthen pan with sesamum oil by the -eldest woman of the family. No metal vessel may be used to hold the water, flour or oil required for these cakes, probably because earthen vessels were employed before metal ones and are therefore considered more sacred. In measuring the ingredients a quarter of a measure is always taken in excess, such as a seer ^ and a quarter for a seer of wheat, to foreshadow the perpetual increase of the family. When made the cakes are offered to the Kul Deo or house- hold god.

The god is worshipped and the bride and bride- groom then first partake of the cakes and after them all members of the family and relatives. Married daughters and daughters-in-law may eat of the cakes, but not widows, who are probably too impure to join in a sacred sacrament. Every person admitted to partake of the marriage-cakes is held to belong to the family, so that all other members of ' Hoswellia scrrala. ^ Eugenia jamholana. ^ 2 lbs.

it have to observe impurity for ten days after a birth or death has occurred in his house and shave their heads for a death. When the family is so large that this becomes irksome it is cut down by not inviting persons beyond seven degrees of relationship to the Meher sacrament. This exclusion has sometimes led to bitter quarrels and actions for defamation. It seems likely that the Meher may be a kind of substitute for the sacrificial meal, at which all the members of the clan ate the body of the totem or divine animal, and some similar significance perhaps once attached to the wedding-cake in England, pieces of which are sent to relatives unable to be present at the wedding. Before the wedding the women of each party go and 8. Customs anoint the village gods with oil and turmeric, worshippins' ^' ^^5 fc> fc> _ ^ » ri b wedding. them, and then similarly anoint the bride and bridegroom at their respective houses for three days.

The bridegroom's head is shaved except for his scalp-lock ; he wears a silver necklet on his neck, puts lamp-black on his eyes, and is dressed in new yellow and white clothes. Thus attired he goes round and worships all the village gods and visits the houses of his relatives and friends, who mark his fore- head with rice and turmeric and give him a silver piece. A list of the money thus received is made and similar presents are returned to the donors when they have weddings. The bridegroom goes to the wedding either in a litter or on a horse, and must not look behind him. After being received at the bride's village and conducted to his lodging, he proceeds to the bride's house and strikes a grass mat hung before the house seven times with a reed- stick. On entering the bride's house the bridegroom is taken to worship her family gods, the men of the party usually remaining outside.

Then, as he goes through the room, one of the women who has tied a long thread round her toe gets behind him and measures his height with the thread without his seeing. She breaks off the thread at his height and doubling it once or twice sews it round the top of the bride's skirt, and they think that as long as the bride wears this thread she will be able to make her husband do as she likes. If the girls wish to have a joke they take one of the bridegroom's shoes which he has left

outside the house, wrap it up in a piece of cloth, and place it on a shelf or in a cupboard, where the family god would be kept, with two lamps burning before it. Then they say to the bridegroom, ' Come and worship our household god' ; and if he goes and does reverence to it they unwrap the cloth and show him his own shoe and laugh at him.

But if he has been to one or two weddings and knows the joke he just gives it a kick. The bride's younger brother steals the bridegroom's other shoe and hides it, and will not give it back without a present of a rupee or two.

The bride and bridegroom are seated on wooden seats, and while the Brahman recites texts, they make the following promises. The bridegroom covenants to live with his Avife and her children, to support them and tell her all his concerns, consult her, make her a partner of his religious worship and almsgiving, and be with her on the night following the termination of her monthly impurity. The bride promises to remain faithful to her husband, to obey his wishes and orders, to perform her household duties as well as she can, and not to go anywhere without his permission.

The last promise of the bridegroom has refer- ence to the general rule among Hindus that a man should always sleep with his wife on the night following the termination of her menses because at this time she is most likely to conceive and the prospect of a child being born must not be lost. The Shastras lay it down that a man should not visit his wife before going into battle, this being no doubt an instance of the common custom of abstinence from conjugal intercourse prior to some import-

ant business or undertaking ; but it is stated that if on such an occasion she should have just completed a period of impurity and have bathed and should desire him to come in to her, he should do so, even with his armour on, because by refusing, in the event of his being killed in battle, the chance of a child being born would be finally lost. To Hindu ideas the neglect to produce life is a sin of the same character, though in a minor degree, as that of destroying life ; and it is to be feared that it will be some time before this ingrained superstition gives way to any considerations of prudential restraint. Some people say that for a man

not to visit his wife at this time is as great a sin as murder. The binding- ceremony of the marriage is the walking 9. walking seven times round the marriage-post in the direction of the """""^ ^'^^ 111 sacred sun. Ihe post probably represents the sun and the walk post, of the bridal couple round it may be an imitation of the movement of the planets round the sun. The reverence paid to the marriage-post has already been noticed.

During the procession the bride leads and the bridegroom puts his left hand on her left shoulder. The household pounding-slab is near the post and on it are placed seven little heaps of rice, turmeric, areca-nut, and a small winnowing-fan. Each time the bride passes the slab the bridegroom catches her right foot and with it makes her brush one of the little heaps off the slab. These seven heaps represent the seven Rishis or saints who are the seven large stars of the constellation of the Great Bear. After the wedding the bride and bridegroom resume jq other their seats and the parents of the bride wash their feet in a ^ere- brass tray, marking their foreheads with rice and turmeric. They put some silver in the tray, and other relations and friends do the same.

The presents thus collected go to the bridegroom. The Chandnahu Kurmis then have a ceremony known as palkachdr. The bride's father provides a bed on which a mattress and quilt are laid and the bride and bride- groom are seated on it, while their brother and sister sprinkle parched rice round them. This is supposed to typify the consummation of the marriage, but the ceremony is purely formal as the bridal couple are children. The bridegroom is given two lamps and he has to mix their flames, probably to symbolise the mixing of the spirits of his wife and him- self. He requires a present of a rupee or two before he consents to do so. During the wedding the bride is bathed in the same water as the bridegroom, the joint use of the sacred element being perhaps another symbolic mark of their union. At the feasts the bride eats rice and milk with her husband from one dish, once at her own house and once after she goes to her husband's house. Subsequently she never cats with her husband but always after him. She also sits and eats at the wedding-feasts with her husband's VOL. IV F

II. Poly- gamy, widow- marriage and divorce. relations. This is perhaps meant to mark her admission into her husband's clan. After the wedding the Brahmans on either side recite Sanskrit verses, praising their respective families and displaying their own learning. The competition often becomes bitter and would end in a quarrel, but that the elders of the party interfere and stop it.

The expenses of an ordinary wedding on the bridegroom's side may be Rs. lOO in addition to the bride-price, and on the bride's Rs. 200. The bride goes home for a day or two with the bridegroom's party in Chhattlsgarh but not in the northern Districts, as women accompany the wedding pro- cession in the former but not in the latter locality. If she is too small to go, her shoes and marriage-crown are sent to represent her. When she attains maturity the chauk or gauna ceremony is performed, her husband going to fetch her with a few friends. At this time her parents give her clothes, food and ornaments in a basket called jhanpi or tipara specially prepared for the occasion. A girl who becomes pregnant by a man of the caste before marriage is wedded to him by the rite used for widows.

If the man is an outsider she is expelled from the com- munity. Women are much valued for the sake of their labour in the fields, and the transgressions of a wife are viewed with a lenient eye. In Damoh it is said that a man readily condones his wife's adultery with another Kurmi, and if it becomes known and she is put out of caste, he will give the penalty feasts himself for her admission. If she is detected in a liaison with an outsider she is usually discarded, but the offence may be condoned should the man be a Brahman. And one instance is mentioned of a malguzar's wife who had gone wrong with a Gond, and was forgiven and taken back by her husband and the caste. But the leniency was misplaced as she subsequently eloped with an Ahlr.

Polygamy is usual with those who can afford to pay for several wives, as a wife's labour is more efficient and she is a more profitable investment than a hired servant. An instance is on record of a blind Kurmi in Jubbulpore, who had nine wives. A man who is faithful to one wife, and does not visit her on fast-days, is called a Brahmachari or saint and it is thought that he will go to heaven. The

remarriage of widows is permitted and is usual. The widow goes to a well on some night in the dark fortnight, and leaving her old clothes there puts on new ones which are given to her by the barber's wife. She then fills a pitcher with water and takes it to her new husband's house. He meets her on the threshold and lifts it from her head, and she goes into the house and puts bangles on her wrists. The following saying shows that the second marriage of widows is looked upon as quite natural and normal by the cultivating castes : "If the clouds are like partridge feathers it will rain, and if a widow puts lamp-black on her eyes she will marry again ; these things are certain." -^ A bachelor marrying a widow must first go through the ceremony with a ring which he thereafter wears on his finger, and if it is lost he must perform a funeral ceremony as if a wife had died.

If a widower marries a girl she must wear round her neck an image of his first wife. A girl who is twice married by going round the sacred post is called Chandelia and is most unlucky. She is considered as bad or worse than a widow, and the people sometimes make her live outside the village and forbid her to show them her face. Divorce is open to either party, to a wife on account of the impotency or ill-treatment of her husband, and to a husband for the bad character, ill-health or quarrelsome disposition of his wife. A deed of divorce is executed and delivered before the caste committee.

During her periodical impurity, which lasts for four or five 12. im- days, a woman should not sleep on a cot. She must not walk ^vonien°^ across the shadow of any man not her husband, because it is thought that if she does so her next child will be like that man. Formerly she did not see her husband's face for all these days, but this rule was too irksome and has been abandoned. She should eat the same kind of food for the whole period, and therefore must take nothing special on one day which she cannot get on other days. At this time she will let her hair hang loose, taking out all the cotton strings by which it is tied up." These strings, being cotton, have become ^ Elliot, Hoshangabad Settlaneiit - The custom is pointed out by Mr. Report, p. 115. A. K. Smith, C.S.

impure, and must be thrown away. But if there is no other woman to do the household work and she has to do it her- self, she will keep her hair tied up for convenience, and only throw away the strings on the last day when she bathes. All cotton things are rendered impure by her at this time, and any cloth or other article which she touches must be washed before it can be touched by anybody else ; but

woollen cloth, being sacred, is not rendered impure, and she

can sleep on a woollen blanket without its thereby becoming a defilement to other persons. When bathing at the end of the period a woman should see no other face but her husband's; but as her husband is usually not present, she wears a ring with a tiny mirror and looks at her own face in this as a

substitute. If a woman desires to procure a miscarriage she eats a raw papaya fruit, and drinks a mixture of ginger, sugar, bamboo leaves and milk boiled together. She then has her abdomen well rubbed by a professional masseuse, who comes at a time when she can escape observation. After a pro-

longed course of this treatment it is said that a miscarriage

is obtained. It would seem that the rubbing is the only treatment which is directly effective. The papaya, which is a very digestible fruit, can hardly be of assistance, but may be eaten from some magical idea of its resemblance to a foetus.

The mixture drunk is perhaps designed to be a tonic to the stomach against the painful effects of the massage.

Pregnancy

As regards pregnancy Mr. Marten writes as follows : ^ " A rk«^ woman in pregnancy is in a state of taboo and is peculiarly liable to the influence of magic and in some respects danger- ous to others. She is exempt from the observance of fasts, is allowed any food she fancies, and is fed with sweets and all sorts of rich food, especially in the fifth month. She should not visit her neighbour's houses nor sleep in any open place. Her clothes are kept separate from others. She is subject to a large number of restrictions in her ordinary life with a view of avoiding everything that might prejudice or retard her delivery. She should eschew all red clothes or red things of any sort, such as suggest blood, till the third or 1 Central Provinces Census Report (191 1), p. 153.

fourth month, when conception is certain. She will be care- ful not to touch the dress of any woman who has had a mis- carriage. She will not cross running water, as it might cause premature delivery, nor go near a she-buffalo or a mare lest delivery be retarded, since a mare is twelve months in foal. If she does by chance approach these animals she must propitiate them by offerings of grain. Nor in some cases will she light a lamp, for fear the flame in some way may hurt the child. She should not finish any sowing, pre- viously begun, during pregnancy, nor should her husband thatch the house or repair his axe. An eclipse is particularly dangerous to the unborn child and she must not leave the house during its continuance, but must sit still with a stone pestle in her lap and anoint her womb with cowdung. Under no circumstances must she touch any cutting instrument as it might cause her child to be born mutilated. " During the fifth month of pregnancy the family gods are worshipped to avoid generally any difficulties in her labour. Towards the end of that month and sometimes in the seventh month she rubs her body with a preparation of gram-flour, castor-oil and turmeric, bathes herself, and is clothed with new garments and seated on a wooden stool in a space freshly cleaned and spread with cowdung. Her lap is then filled with sweets called pakwdn made of cocoanut.

A similar ceremony called Boha Jewan is sometimes performed in the seventh or eighth month, when a new sari is given to her and grain is thrown into her lap. Another special rite is the Pansavaji ceremony, performed to remove all defects in the child, give it a male form, increase its size and beauty, give it wisdom and avert the influence of evil spirits." Pregnant women sometimes have a craving for eating earth.

14. Earth-

They eat the earth which has been mixed with wheat ^-'^""S- on the threshing-floor, or the ashes of cowdung cakes which have been used for cooking. They consider it as a sort of medicine which will prevent them from vomiting. Children also sometimes get the taste for eating earth, licking it up from the floor, or taking pieces of lime-plaster from the walls. Possibly they may be attracted by the saltish taste, but the result is that they get ill and their stomachs are distended. The Panwar women of Balaghat eat red and

15. Cus- toms at birth. 16. Treat- ment of mother and child. white clay in order that their children may be born with red and white complexions. During the period of labour the barber's wife watches over the case, but as delivery approaches hands it over to a recognised midwife, usually the Basorin or Chamarin, who remains in the lying-in room till about the tenth day after delivery. " If delivery is retarded," Mr. Marten continues,^ " pressure and massage are used, but coffee and other herbal decoctions are given, and various means, mostly depending on sympathetic magic, are employed to avert the adverse spirits and hasten and ease the labour.

She may be given water to drink in which the feet of her husband ^ or her mother-in-law or a young unmarried girl have been dipped, or she is shown the sivastik or some other lucky sign, or the cJiakra-vyuha, a spiral figure showing the arrangement of the armies of the Pandavas and Kauravas which resembles the intestines with the exit at the lower end." The menstrual blood of the mother during child-birth is efficacious as a charm for fertility. The Nain or Basorin will sometimes try and dip her big toe into it and go to her house.

There she will wash her toe and give the water to a barren woman, who by drinking it will transfer to herself the fertility of the woman whose blood it is. The women of the family are in the lying-in room and they watch her carefully, while some of the men stand about outside. If they see the midwife coming out they examine her, and if they find any blood exclaim, ' You have eaten of our salt and will you play us this trick ' ; and they force her back into the room where the blood is washed off. All the stained clothes are washed in the birth-room, and the water as well as that in which the mother and child are bathed is poured into a hole dug inside the room, so that none of it may be used as a charm.

The great object of the treatment after birth is to pre- vent the mother and child from catching cold. They appear to confuse the symptoms of pneumonia and infantile lockjaw in a disease called sanpdt, to the prevention of which their efforts are directed. A sigii or stove is kept alight under the bed, and in this the seeds of ajwdiii or coriander are • C.P. Census Repri {i^ii), \x 153. ^ Or his big toe.

burnt. The mother eats the seeds, and the child is waved over the stove in the smoke of the burning ajivdin. Raw asafoetida is put in the woman's ears wrapped in cotton- wool, and she eats a little half-cooked. A freshly-dried piece of cowdung is also picked up from the ground and half-burnt and put in water, and some of this water is given to her to drink, the process being repeated every day

for a month. Other details of the treatment of the mother and child after birth are given in the articles on Mehtar and

Kunbi.

For the first five days after birth the child is given a little honey and calf's urine mixed. If the child coughs it is given bans-lochan, which is said to be some kind of silicate found in bamboos. The mother does not suckle the child for three days, and for that period she is not washed and nobody goes near her, at least in Mandla. On the third day after the birth of a girl, or the fourth after that of a boy, the mother is washed and the child is then suckled by her for the first time, at an auspicious moment pointed out by the astrologer.

Generally speaking the whole treat- ment of child-birth is directed towards the avoidance of various imaginary magical dangers, while the real sanitary precautions and other assistance which should be given to the mother are not only totally neglected, but the treatment employed greatly aggravates the ordinary risks which a woman has to take, especially in the middle and higher castes. When a boy is born the father's younger brother or one 17. cere- of his friends lets off a gun and beats a brass plate to pro- "1°"'^- '^ . =^f'^r birth.

claim the event. The women often announce the birth of a boy by saying that it is a one-eyed girl.

This is in case any enemy should hear the mention of the boy's birth, and the envy felt by him should injure the child. On the sixth day after the birth the Chhathi ceremony is performed and the mother is given ordinary food to eat, as described in the article on Kunbi. The twelfth day is known as Barhon or Chauk. On this day the father is shaved for the first time after the child's birth. The mother bathes and cugs the nails of her hands and feet ; if she is living by a river she throws them into it, otherwise on to the roof of the house. The father and mother sit in the chauk or space marked out

for worship with cowdung and flour ; the woman is on the man's left side, a woman being known as Bamangi or the left limb, either because the left limb is weak or because woman is supposed to have been made from man's left side, as in Genesis. The household god is brought into the chauk and they worship it. The Bua or husband's sister brings presents to the mother known as b/iariz, for filling her lap : silver or gold bangles if she can afford them, a coat and cap for the boy ; dates, rice and a breast-cloth for the mother ; for the father a rupee and a cocoanut. These things are placed in the mother's lap as a charm to sustain her fertility. The father gives his sister back double the value of the presents if he can afford it.

He gives her husband a head-cloth and shoulder-cloth ; he waves two or three pice round his wife's head and gives them to the barber's wife. The latter and the midwife take the clothes worn by the mother at child-birth, and the father gives them each a new cloth if he can afford it. The part of the navel- string which falls off the child's body is believed to have the power of rendering a barren woman fertile, and is also intimately connected with the child's destiny.

It is there- fore carefully preserved and buried in some auspicious place, as by the bank of a river. In the sixth month the Pasni ceremony is performed, when" the child is given grain for the first time, consisting of rice and milk. Brahmans or religious mendicants are invited and fed. The child's hair and nails are cut for the first time on the Shivratri or Akti festival following the birth, and are wrapped up in a ball of dough and thrown into a sacred river.

If a child is born during an eclipse they think that it will suffer from lung disease ; so a silver model of the moon is made immediately during the eclipse, and hung round the child's neck, and this is supposed to preserve it from harm. i8. Suck- A Hindu woman will normally suckle her child for two to three years after its birth, and even beyond this up to six years if it sleeps with her. But they think that the child becomes short of breath if suckled for so long, and advise the mother to wean it. And if she becomes pregnant again, when she has been three or four months in this condition, children

she will wean the child by putting nim leaves or some other bitter thing on her breasts. A Hindu should not visit his wife for the last six months of her pregnancy nor until the child has been fed with grain for the first time six months after its birth. During the former period such action is thought to be a sin, while during the latter it may have the effect of rendering the mother pregnant again too quickly, and hence may not allow her a sufficiently long period to suckle the first child. Twins, Mr. Marten states, are not usually considered to 19- Beliefs be inauspicious.^ "It is held that if they are of the same \^r^\^^_ sex they will survive, and if they are of a different sex one of them will die. Boy twins are called Rama and Lachh- man, a boy and a girl Mahadeo and Parvati, and two girls Ganga and Jamuni or Sita and Konda. They should always be kept separate so as to break the essential connection which exists between them and may cause any misfortune which happens to the one to extend to the other. Thus the mother always sleeps between them in bed and never carries both of them nor suckles both at the same time.

Again, among some castes in Chhattlsgarh, when the twins are of different sex, they are considered to be pap (sinful) and are called Papi and Papin, an allusion to the horror of a brother and sister sharing the same bed (the mother's womb)." Hindus think that if two people comb their hair with the same comb they will lose their affection for each other. Hence the hair of twins is combed with the same comb to weaken the tie which exists between them, and may cause the illness or death of either to follow on that of the other.

The dead are usually burnt with the head to the north. 20. Dis- Children whose ears have not been bored and adults who J^^^^J °\ the dead. die of smallpox or leprosy are buried, and members of poor families who cannot afford firewood. If a person has died by hanging or drowning or from the bite of a snake, his body is burnt without any rites, but in order that his soul may be saved, the Iiojii sacrifice is performed subsequently to the cremation. Those who live near the Nerbudda and Mahanadi sometimes throw the bodies of the dead into these rivers and think that this will make thep go to heaven. 1 C.P. Ceiistts Pc'/or/ (igi I), p. 15S.

The following account of a funeral ceremony among the middle and higher castes in Saugor is mainly furnished by Major W. D. Sutherland, I. M.S., with some additions from Mandla, and from material furnished by the Rev. E. M. Gordon : ^ " When a man is near his end, gifts to Brahmans are made by him, or by his son on his behalf These, if he is a rich man, consist of five cows with their calves, marked on the forehead and hoofs with turmeric, and with garlands of flowers round their necks. Ordinary people give the price of one calf, which is fictitiously taken at Rs. 3-4, Rs. 1-4, ten annas or five annas according to their means. By holding on to the tail of this calf the dead man will be able to swim across the dreadful river Vaitarni, the Hindu Styx. This calf is called Bachra Sankal or ' the chain-calf,' as it furnishes a chain across the river, and it may be given three times, once before the death and twice afterwards.

When near his end the dying man is taken down from his cot and laid on a woollen blanket spread on the ground, perhaps with the idea that he should at death be in contact with the earth and not suspended in mid-air as a man on a cot is held to be. In his mouth are placed a piece of gold, some leaves of the tulsi or basil plant, or Ganges water, or rice cooked in Jagannath's temple. The dying man keeps on rejDeating ' Ram, Ram, Sitaram.' " 21. Funeral As soon as death occurs the corpse is bathed, clothed and smeared with a mixture of powdered sandalwood, camphor and spices.

A bier is constructed of planks, or if this cannot be afforded the man's cot is turned upside down and the body is carried out for burial on it in this fashion, with the legs of the cot pointing upwards. Straw is laid on the bier, and the corpse, covered with fine white cloth, is tied securely on to it, the hands being crossed on the breast, with the thumbs and great toes tied together. When a married woman dies she is covered with a red cloth which reaches only to the neck, and her face is left open to the view of everybody, whether she went abroad unveiled in her life or not. It is considered a highly auspicious thing for a woman to die in the lifetime of her husband and children, and the corpse is sometimes dressed like a bride and ' ' In Indian Folk Tales. rites.

ornaments put on it. The corpse of a widow or girl is wrapped in a white cloth with the head covered. At the head of the funeral procession walks the son of the deceased, or other chief mourner, and in his hand he takes smouldering cowdung cakes in an earthen pot, from which the pyre will be kindled. This fire is brought from the hearth of the house by the barber, and he sometimes also carries it to the pyre. On the way the mourners change places so that each may assist in bearing the bier, and once they set the bier on the ground and leave two pice and some grain where it lay, before taking it up again.

After the funeral each person who has helped to carry it takes up a clod of earth and with it touches successively the place on his shoulder where the bier rested, his waist and his knee, afterwards dropping the clod on the ground. It is believed that by so doing he removes from his shoulder the weight of the corpse, which would otherwise press on it for some time. At the cremation-ground the corpse is taken from the 22. Burn- bier and placed on the pyre.

The cloth which covered it IJ^I^] ^ and that on which it lay are given to a sweeper, who is always present to receive this perquisite. To the corpse's mouth, eyes, ears, nostrils and throat is applied a mixture of barley-flour, butter, sesamum seeds and powdered sandal- wood. Logs of wood and cowdung cakes are then piled on the body and the pyre is fired* by the son, who first holds a burning stick to the mouth of the corpse as if to inform it that he is about to apply the fire.

The pyre of a man is fired at the head and of a woman at the foot. Rich people burn the corpse with sandalwood, and others have a little of this, and incense and sweet-smelling gum. Nowadays if the rain comes on and the pyre will not burn they use kerosine oil. When the body is half-consumed the son takes up a piece of wood and with it strikes the skull seven times, to break it and give exit to the soul. This, however, is not always done. The son then takes up on his right shoulder an earthen pot full of water, at the bottom of which is a small hole.

He walks round the pyre three times in

the direction of the sun's course and stands facing to the south, and dashes the pot on the ground, crying out in his grief, * Oh, my father.' While this is going on mantras or

sacred verses are recited by the officiating Brahman. When the corpse is partly consumed each member of the assembly throws the Pdnch lakariya (five pieces of wood or sprigs of basil) on to the pyre, making obeisance to the deceased and saying, ' Swarg ko jao,' or 'Ascend to heaven.' Or they may say, ' Go, become incarnate in some human being.' They stay by the corpse for i^ pahars or watches or some four hours, until either the skull is broken by the chief mourner or breaks of itself with a crack. Then they bathe and come home and after some hours again return to the corpse, to see that it is properly burnt. If the pyre should go out and a dog or other animal should get hold of the corpse when it is half-burnt, all the relatives are put out of caste, and have to give a feast to all the caste, costing for a rich family about Rs. 50 and for a poor one Rs. 10 to Rs. 15.

Then they return home and chew nim leaves, which are bitter and purifying, and spit them out of their mouth, thus severing their connection with the corpse. When the mourners have left the deceased's house the women of the family bathe, the bangles of the widow are broken, the vermilion on the parting of her hair and the glass ornament {tikli) on her forehead are removed, and she is clad in white clothing of coarse texture to show that henceforth she is only a widow. On the third day the mourners go again and collect the ashes and throw them into the nearest river. The bones are placed in a silken bag or an earthen pot or a leaf basket, and taken to the Ganges or Nerbudda within ten days if possible, or otherwise after a longer interval, being buried meantime. Some milk, salt and calf's urine are sprinkled over the place where the corpse was burnt. These will cool the place, and the soul of the dead will similarly be cooled, and a cow will probably come and lick up the salt, and this will sanctify the place and also the soul.

When the bones are to be taken to a sacred river they are tied up in a little piece of cloth and carried at the end of a stick by the chief mourner, who is usually accompanied by several caste-fellows. At night during the journey this stick is planted in the ground, so that the bones may not touch the earth.

Burial

Gravcs are always dug from north to south. Some people say that heaven is to the north, being situated in the

Himalayas, and others that in the Satyug or Golden Age the sun rose to the north. I'he digging of the grave only com- mences on the arrival of the funeral party, so there is of necessity a delay of several hours at the site, and all who attend a funeral are supposed to help in digging. It is considered to be meritorious to assist at a burial, and there is a saying that a man who has himself conducted a hundred funerals will become a Raja in his next birth. When the grave has been filled in and a mound raised to mark the spot, each person present makes five small balls of earth and places them in a heap at the head of the grave.

This custom is also known as PdncJi lakariya, and must therefore be an imitation of the placing of the five sticks on the pyre ; its original meaning in the latter case may have been that the mourners should assist the family by bringing a contribution of wood to the pyre. As adopted in burial it seems to have no special significance, but somewhat resembles the European custom of the mourners throwing a little dust into the grave.

Return

On the third day the pindas or sacrificial cakes are offered and this goes on till the tenth day. These cakes °^ '^'^ '°"'- are not eaten by the priest or Maha-Brahman, but are thrown into a river. On the evening of the third day the son goes, accompanied by a Brahman and a barber, and carrying a key to avert evil, to a pipal ^ tree, on whose branches he hangs two earthen pots : one containing water, which trickles out through a hole in the bottom, and the other a lamp. On each succeeding night the son replenishes the contents of these pots, which are intended to refresh the spirit of the deceased and to light it on its way to the lower world.

In some localities on the evening of the third day the ashes of the cooking-place are sifted, and laid out on a tray at night on the spot where the deceased died, or near the cooking- place. In the morning the layer of ashes is inspected, and if what appears to be a hand- or footprint is seen, it is held that the spirit of the deceased has visited the house. Some people look for handprints, some for footprints, and some for both, and the Nais look for the print of a cow's hoof, which when seen is held to prove that the deceased in con- sideration of his singular merits has been reborn a cow. If 1 Fiais R.

a woman has died in child-birth, or after the birth of a child and before the performance of the sixth-day ceremony of purification, her hands are tied with a cotton thread when she is buried, in order that her spirit may be unable to rise and trouble the living. It is believed that the souls of such women become evil spirits or Chiirels. Thorns are also placed over her grave for the same purpose. 25. Mourn- During the days of mourning the chief mourner sits '"^' apart and does no work. The others do their work but do not touch any one else, as they are impure. They leave their hair unkempt, do not worship the gods nor sleep on cots, and abjure betel, milk, butter, curds, meat, the wearing of shoes, new clothes and other luxuries. In these days the friends of the family come and comfort the mourners with conversation on the shortness and uncertainty of human life and kindred topics. During the period of mourning when the family go to bathe they march one behind the other in Indian file.

And on the last day all the people of the village accompany them, the men first and after they have returned the women, all marching one behind the other. They also come back in this manner from the actual funeral, and the idea is perhaps to prevent the dead man's spirit from follow- ing them. He would probably feel impelled to adopt the same formation and fall in behind the last of the line, and then some means is devised, such as spreading thorns in the path, for leaving him behind. 26. Shav- On the ninth, tenth or eleventh day the males of the family ing, and ]-^ave the front of the head from the crown, and the beard and presents to Brahmans. moustaches,shaved in token ofmourning.

The Maha-Brahman who receives the gifts for the dead is shaved with them. This must be done for an elder relation, but a man need not be shaved on the death of his wife, sister or children. The day is the end of mourning and is called Gauri Ganesh, Gauri being Parvati or the wife of Siva, and Ganesh the god of good fortune. On the occasion the family give to the Maha-Brahman ' a new cot and bedding with a cloth, an umbrella to shield the spirit from the sun's rays, a copper vessel full of water to quench its thirst, a brass lamp to guide it on its journey, and if the family is well-to-do a 1 He is also known as Katia or Kattaha Brahman and as Mahapatra.

horse and a cow. All these things are meant to be for the use of the dead man in the other world. It is also the Brahman's business to eat a quantity of cooked food, which will form the dead man's food. It is of great spiritual importance to the dead man's soul that the Brahman should finish the dish set before him, and if he does not do so the soul will fare badly. He takes advantage of this by stop- ping in the middle of the meal, saying that he has eaten all he is capable of and cannot go on, so that the relations have to give him large presents to induce him to finish the food.

These Maha-Brahmans are utterly despised and looked down on by all other Brahmans and by the community generally, and arc sometimes made to live outside the village. The regular priest, the Malai or Purohit, can accept no gifts from the time of the death to the end of the period pf mourning. Afterwards he also receives presents in money according to the means of his clients, which it is supposed will benefit the dead man's soul in the next world ; but no disgrace attaches to the acceptance of these. When the mourning is complete on the Gauri-Ganesh 27.

End of day all the relatives take their food at the chief mourner's mourning. house, and afterwards the pancJidyat invest him with a new turban provided by a relative. On the next bazar day the members of the panchdyat take him to the bazar and tell him to take up his regular occupation and earn his livelihood. Thereafter all his relatives and friends invite him to take food at their houses, probably to mark his accession to the position of head of the family. Three months, six months and twelve months after the 28. Anni- death presents are made to a Brahman, consisting of Sidha, [he^dead.° or butter, wheat and rice for a day's food. The anniversaries of the dead are celebrated during Pitripaksh or the dark fortnight of Kunwar (September-October).

If a man died on the third day of any fortnight in the year, his anniversary is celebrated on the third day of this fortnight and so on. On that day it is supposed that his spirit will visit his earthly house where his relatives reside. But the souls of women all return to their homes on the ninth day of the fortnight, and on the thirteenth day come the souls of all those who have met with a violent death, as by a fall, or have been killed by wild animals or snakes.

Beliefs in the hereafter

== Religion==. Village gods.

The spirits of such persons are supposed, on account of their untimely end, to entertain

a special grudge against the living. As regards the belief in the hereafter Mr. Gordon writes : ^ " That they have the idea of hell as a place of punishment may be gathered from the belief that when salt is spilt the one who does this will in Fatal or the infernal region have

to gather up each grain of salt with his eyelids. Salt is for this reason handed round with great care, and it is considered unlucky to receive it in the palm of the hand ; it is therefore invariably taken in a cloth or vessel. There is a belief that the spirit of the deceased hovers round familiar scenes and places, and on this account, whenever possible, a house in

which any one has died is destroyed or deserted.

After the spirit has wandered round restlessly for a certain time it is said that it will again become incarnate and take the form either of man or of one of the lower animals." In Mandla they think that the soul after death is arraigned and judged before Yama, and is then chained to a flaming pillar for a longer or shorter period according to its sins. The gifts made to Brahmans for the dead somewhat shorten the period. After that time it is born again with a good or bad body and human or animal according to its deserts.

The caste worship the principal Hindu deities. Either Bhagwan or Parmeshwar is usually referred to as the supreme deity, as we speak of God. Bhagwan appears to be Vishnu or the Sun, and Parmeshwar is Siva or Mahadeo. There are few temples to Vishnu in villages, but none are required as the sun is daily visible. Sunday or Raviwar is the day sacred to him, and some people fast in his honour on Sundays, eating only one meal without salt. A man salutes the sun after he gets up by joining his hands and looking towards it, again when he has washed his face, and a third time when he has bathed, by throwing a little water in the sun's direc- tion.

He must not spit in front of the sun nor perform the lower functions of the body in its sight. Others say that the sun and moon are the eyes of God, and the light of the sun is the effulgence of God, because by its light and heat all moving and immobile creatures sustain their life and all ^ Indian Folk Tales, p. 54.

corn and other products of the earth grow. In his incarna- tions of Rama and Krishna there are temples to Vishnu in large villages and towns. Khermata, the mother of the village, is the local form of Devi or the earth-goddess. She has a small hut and an image of Devi, either black or red. She is worshipped by a priest called Panda, who may be of any caste except the impure castes. The earth is worshipped in various ways. A man taking medicine for the first time in an illness sprinkles a few drops on the earth in its honour. Similarly for the first three or four times that a cow is milked after the birth of a calf the stream is allowed to fall on the ground.

A man who is travelling offers a little food to the earth before eating himself Devi is sometimes considered to be one of seven sisters, but of the others only two are known, Marhai Devi, the goddess of cholera, and Sitala Devi, the goddess of smallpox. When an epidemic of cholera breaks out the Panda performs the following ceremony to avert it. He takes a kid and a small pig or chicken, and some cloth, cakes, glass bangles, vermilion, an earthen lamp, and some country liquor, which is sprinkled all along the way from where he starts to where he stops. He proceeds in this manner to the boundary of the village at a place where there are cross-roads, and leaves all the things there. Sometimes the animals are sacrificed and eaten.

While the Panda is doing this every one collects the sweepings of his house in a winnowing -fan and throws them outside the village boundary, at the same time ringing a bell continu- ously. The Panda must perform his ceremony at night and, if possible, on the day of the new moon. He is accompanied by a iQ.\v other low-caste persons called Gunias. A Gunia is one who can be possessed by a spirit in the temple of Khermata. When possessed he shakes his head up and down violently and foams at the mouth, and sometimes strikes his head on the ground.

Another favourite godling is Hardaul, who was the brother of Jujhar Singh, Rfija of Orchha, and was suspected by Jujhar Singh of loving the latter's wife, and poisoned in consequence by his orders. Hardaul has a platform and sometimes a hut with an image of a man on horseback carrying a spear in his hand. His shrine is outside the village, and two days before a marriage the VOL. IV G

women of the family visit his shrine and cook and eat their food there and invite him to the wedding. Clay horses are offered to him, and he is supposed to be able to keep off rain and storms during the ceremony. Hardaul is perhaps the deified Rajput horseman. Hanuman or Mahablr is repre- sented by an image of a monkey coloured with vermilion, with a club in his hand and a slain man beneath his feet. He is principally worshipped on Saturdays so that he may counteract the evil influences exercised by the planet Saturn on that day.

His image is painted with oil mixed with ver- milion and has a wreath of flowers of the cotton tree ; and g'uo-al or incense made of resin, sandalwood and other ingredients is burnt before him. He is the deified ape, and is the god of strength and swiftness, owing to the exploits performed by him during Rama's invasion of Ceylon. Dulha Deo is another godling whose shrine is in every village. He was a young bridegroom who was carried off by a tiger on his way to his wedding, or, according to another account, was turned into a stone pillar by a flash of lightning. Before the start- ing of a wedding procession the members go to Dulha Deo and offer a pair of shoes and a miniature post and marriage- crown. On their return they offer a cocoanut. Dulha Deo has a stone and platform to the east of the village, or occasionally an image of a man on horseback like Hardaul. Mirohia is the god of the field boundary. There is no sign of him, but every tenant, when he begins sowing and cutting the crops, offers a little curds and rice and a cocoanut and lays them on the boundary of the field, saying the name of Mirohia Deo. It is believed among agriculturists that if this godling is neglected he will flatten the corn by a wind, or cause the cart to break on its way to the threshing- floor. 31. Sowing The sowing of the Jawaras, corresponding to the the gardens of Adonis, takes place during the first nine days Jawaras ^ , I -rr - ^ r^7 • /o 1 or Gardens of the months of Kunwar and Chait (September and of Adonis. ]y[arch).

The former is a nine days' fast preceding the Dasahra festival, and it is supposed that the goddess Devi was during this time employed in fighting the buffalo- demon (Bhainsasur), whom she slew on the tenth day. The latter is a nine days' fast at the new year, preceding

the triumphant entry of Rama into Ajodhia on the tenth day on his return from Ceylon. The first period comes before the sowing of the spring crop of wheat and other grains, and the second is at the commencement of the harvest of the same crop. In some localities the Jawaras are also grown a third time in the rains, probably as a preparation for the juari sowings,^ as juari is planted in the baskets or ' gardens ' at this time. On the first day a small room is cleared and whitewashed, and is known as the dizvdla or temple. Some earth is brought from the fields and mixed with manure in a basket, and a male member of the family sows wheat in it, bathing before he does so.

The basket is kept in the diwdla and the same man attends on it through- out the nine days, fasting all day and eating only milk and fruit at night, A similar nine days' fast was observed by the Eleusinians before the sacramental eating of corn and the worship of the Corn Goddess, which constituted the Eleusinian mysteries." During the period of nine days, called the Naoratra, the plants are watered, and long stalks spring up. On the eighth day the hom or fire offering is performed, and the Gunias or devotees are possessed by Devi. On the evening of the ninth day the women, putting on their best clothes, walk out of the houses with the pots of grain on their heads, singing songs in praise of Devi. The men accompany them beating drums and cymbals. The devotees pierce their cheeks with long iron needles and walk in the procession.

High-caste women, who cannot go themselves, hire the barber's or waterman's wife to go for them. The pots are taken to a tank and thrown in, the stalks of grain being kept and distributed as a mark of amity. The wheat which is sown in Kunwar gives a forecast of the spring crops. A plant is pulled out, and the return of the crop will be the same number of times the seed as it has roots. The woman who gets to the tank first counts the number of plants in her pot, and this gives the price of wheat in rupees per mdiii} Sometimes marks of red rust appear on the plants, and this shows that the crop will suffer from rust.

The ceremony performed in Chait is said to be a sort of ^ Sorghiiiii vulgare, a large millet. History of Religion, p. 365. ^ Dr. Jevons, Introduction to the "^ A measure of 400 lbs.

harvest thanksgiving. On the ninth day of the autumn ceremony another celebration called ' Jhinjhia ' or ' Norta ' takes place in large villages. A number of young unmarried girls take earthen pots and, making holes in them and placing lamps inside, carry them on their heads through the village, singing and dancing. They receive presents from the villagers, with which they hold a feast. At this a small platform is erected and two earthen dolls, male and female, are placed on it ; rice and flowers are offered to them and their marriage is celebrated. 32. Rites The following observances in connection with the crops connected ^j.g practised by the agricultural castes in Chhattlsgarh : with the ^ -' ° . ^ crops. The agricultural year begins on Akti or the 3rd day of ^^^j;°^"^jj^°f Baisakh (April-May). On that day a cup made oi palds^ leaves and filled with rice is offered to Thakur Deo. In some villages the boys sow rice seeds before Thakur Deo's shrine with little toy ploughs. The cultivator then goes to his field, and covering his hand with wheat-flour and turmeric, stamps it five times on the plough.

The malguzar takes five handfuls of the seed consecrated to Thakur Deo and sows it, and each of the cultivators also sows a little. After this regular cultivation may begin on any day, though Monday and Friday are considered auspicious days for the commencement of sowing. On the Hareli, or festival of the fresh verdure, which falls on the i 5th day of Shrawan (July-August), balls of flour mixed with salt are given to the cattle. The plough and all the implements of agriculture are taken to a tank and washed, and are then set up in the courtyard of the house and plastered with cowdung. The plough is set facing towards the sun, and butter and sugar are offered to it. An earthen pot is whitewashed and human figures are drawn on it with charcoal, one upside down. It is then hung over the entrance to the house and is believed to avert the evil eye. All the holes in the cattle- sheds and courtyards are filled and levelled with gravel. While the rice is growing, holidays are observed on five Sundays and no work is done. Before harvest Thakur Deo must be propitiated with an offering of a white goat or a black fowl. Any one who begins to cut his crop before this ' Btitea froiidosa. ^4f^

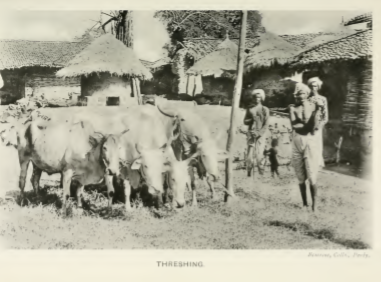

offering has been made to Thakur Deo is fined the price of a goat by the village community. Before threshing his corn each cultivator offers a separate sacrifice to Thakur Deo of a goat, a fowl or a broken cocoanut. Each evening,

on the conclusion of a day's threshing, a wisp of straw is rubbed on the forehead of each bullock, and a hair is then pulled from its tail, and the hairs and straw made into a bundle are tied to the pole of the threshing-floor. The cultivator prays, * O God of plenty ! enter here full and go

out empty.' Before leaving the threshing-floor for the night some straw is burnt and three circles are drawn with

the ashes, one round the heap of grain and the others

round the pole.

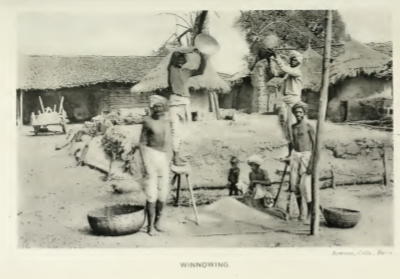

Outside the circles are drawn pictures of the sun, the moon, a lion and a monkey, or of a cart and a pair of bullocks. Next morning before sunrise the ashes are swept away by waving a winnowing-fan over them. This ceremony is called anj'afi chadJiana or placing lamp- black on the face of the threshing-floor to avert the evil eye, as women put it on their eyes. Before the grain is measured it must be stacked in the form of a trapezium with the shorter end to the south, and not in that of a square or oblong heap. The measurer stands facing the east, and having the shorter end of the heap on his left hand. On the larger side of the heap are laid the kalara or hook, a winnowing-fan, the datiri, a rope by which the bullocks are tied to the threshing-pole, one or three branches of the ber or wild plum tree, and the twisted bundle of straw and hair of the bullocks which had been tied to the pole.

On the top of the heap are placed five balls of cowdung, and the ho)n or fire sacrifice is offered to it. The first kdtJia ^ of rice measured is also laid by the heap. The measurer never quite empties his measure while the work is going on, as it is feared that if he does this the god of abundance will leave the threshing-floor. While measuring he should always wear a turban. It is considered unlucky for any one who has ridden on an elephant to enter the threshing-floor, but a person who has ridden on a tiger brings luck. Consequently the Gonds and Baigas, if they capture a young tiger and tame it, will take it round ' A measure containing 9 lb. 2 oz. of rice.

33- Agri- cultural supersti- tions.

the country, and the cultivators pay them a little to give their children a ride on it. To enter a threshing-floor with shod feet is also unlucky. Grain is not usually measured at noon but in the morning or evening. The cultivators think that each grain should bear a hundredfold, but they do not get this as Kuvera, the treasurer of the gods, or Bhainsasur, the buffalo demon who lives in the fields, takes it. Bhainsasur is worshipped when the rice is coming into ear, and if they think he is likely to be mischievous they give him a pig, but otherwise a smaller offering. When the standing corn in the fields is beaten down at night they think that Bhainsasur has been passing over it.

He also steals the crop while it is being cut and is lying on the ground. Once Bhainsasur was absent while the particular field in the village from which he stole his supply of grain was cut and the crop removed, and after- wards he was heard crying that all his provision for the year had been lost. Sometimes the oldest man in the house cuts the first five bundles of the crop, and they are afterwards left in the field for the birds to eat.

And at the end of harvest the last one or two sheaves are left standing in the field, and any one who likes can cut and carry them away. In some localities the last stalks are left standing in the field and are known as barJiona or the giver of increase. Then all the labourers rush together at this last patch of corn and tear it up by the roots ; everybody seizes as much as he can and keeps it, the master having no share in this patch. After the barhona has been torn up all the labourers fall on their faces to the ground and worship the field. In other places the barhona is left standing for the birds to eat.

This custom arises from the belief demonstrated by Sir J. G. Frazer in The Golden Bough that the corn-spirit takes refuge in the last patch of grain, and that when it is cut he flies away or his life is extinguished. And the idea is supported by the fact that the rats and other vermin, who have been living in the field, seek shelter in the last patch of corn, and when this is cut have to dart out in front of the reapers. In some countries it is thought, as shown by Sir J. G. Frazer, that the corn-spirit takes refuge in the body of one of these animals.

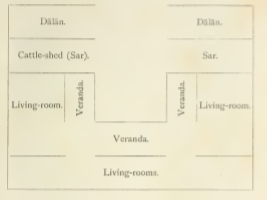

The house of a malguzar or good tenant stands in a 34- courtyard or angan 45 to 60 feet square and surrounded by a brick or mud wall. below :- The plan of a typical house is shown Dalan.

tobacco, maize or vegetables are grown. The interior is dark, for light is admitted only by the low door, and the smoke-stained ceiling contributes to the gloom. The floor is of beaten earth well plastered with cowdung, the plastering being repeated weekly. 35. Super- The following are some superstitious beliefs and customs stitions about houses. A house should face north or east and not about houses. south or wcst, as the south is the region of Yama, the god of death, who lives in Ceylon, and the west the quarter of the setting sun. A Muhammadan's house, on the other hand, should face south or west because Mecca lies to the south-west.

A house may have verandas front and back, or on the front and two sides, but not on all four sides. The front of a house should be lower than the back, this shape being known as gai-vinkh or cow-mouthed, and not higher than the back, which is singh-miikh or tiger-mouthed. The front and back doors should not be in a straight line, which would enable one to look right through the house. The angan or compound of a house should be a little longer than it is wide, no matter how little. Conversely the build- ing itself should be a little wider along the front than it is long from front to rear.

The kitchen should always be on the right side if there is a veranda, or else behind. When an astrologer is about to found a house he calculates the direction in which Shesh Nag, the snake on whom the world reposes, is holding his head at that time, and plants the first brick or stone to the left of that direction, because snakes and elephants do not turn to the left but always to the right. Consequently the house will be more secure and less likely to be shaken down by Shesh Nag's movements, which cause the phenomenon known to us as an earthquake. Below the foundation-stone or brick are buried a pice, an areca-nut and a grain of rice, and it is lucky if the stone be laid by a man who has been faithful to his wife. There should be no echo in a house, as an echo is considered to be the voice of evil spirits.

The main beam should be placed in position on a lucky day, and the carpenter breaks a cocoanut against it and receives a present. The width of the rooms along the front of a house should be five cubits each, and if there is a staircase it must have an uneven

number of steps. The door should be low so that a man must bend his head on entering and thus show respect to the household god. The floor of the verandas should be lower than that of the room inside ; the Hindus say that the compound should not see the veranda nor the veranda the house. But this rule has of course also the advantage of keeping the house-floor dry.

If the main beam of a house breaks it is a very bad omen, as also for a vulture or kite to perch on the roof; if this should happen seven days running the house will inevitably be left empty by sickness or other misfortune. A dog howling in front of the house is very unlucky, and if, as may occasionally happen, a dog should get on to the roof of the house and bark, the omen is of the worst kind. Neither the pipal nor banyan trees should be planted in the yard of a house, because the leavings of food might fall upon them, and this would be an insult to the deities who inhabit the sacred trees. Neither is it well to plant the 7il)n tree, because the ni7n is the tree of anchorites, and the frequent contemplation of it will take away from a man the desire of offspring and lead to the extinction of his family. Bananas should not be grown close to the house, because the sound of this fruit bursting the pod is said to be audible, and to hear it is most unlucky.

It is a good thing to have a giilar^ tree in the yard, but at a little distance from the house so that the leavings of food may not fall upon it ; this is the tree of the saint Dattatreya, and will cause wealth to increase in the house. A plant of the sacred tulsi or basil is usually kept in the yard, and every morning the householder pours a vessel of water over it as he bathes, and in the evening places a lamp beside it.

This holy plant sanctifies the air which passes over it to the house. No one should ever sit on the threshold of a house ; this is the seat of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, and to sit on it is disrespectful to her. A house should never be swept at twilight, because it is then that Lakshmi makes her rounds, and she would curse it and pass by. At this time a lamp should be lighted, no one should be allowed to sleep, and even if a man is sick he should sit up on his bed.

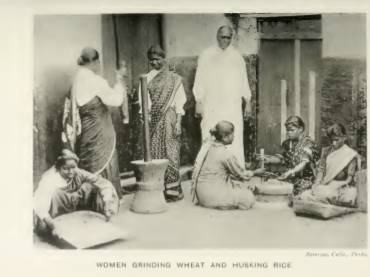

At this time the grinding-mill should not be turned nor grain be husked, but reverence should be paid to ancestors and to the household deities. No one must sit on the grinding-mill ; it is regarded as a mother because it gives out the flour by which the family is fed. No one must sit on cowdung cakes because they are the seat of Saturn, the Evil One, and their smell is called Samchar ke bds. No one must step on the chrdha or cooking-hearth nor jar it with his foot. At the midday meal, when food is freshly cooked, each man will take a little fire from the hearth and place it in front of him, and will throw a little of everything he eats on to the fire, and some ghi as an offering to Agni, the god of fire. And he will also walk round the hearth, taking water in his hand and then throwing it on the ground as an offering to Agni. A man should not sleep with his feet to the south, because a corpse is always laid in that direction. He should not sleep with his feet to the east, nor spit out water from his mouth in the direction of the east. 36. Furni- Of furniture there is very little.