Kohinoor/ Koh-i-Noor

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A backgrounder

Anmol Jain, Sep 19, 2022: The Times of India

MUSSOORIE: The demise of Queen Elizabeth II and the subsequent talks of the Kohinoor to be inherited by Camilla, the Queen consort, have reminded Mussoorie residents of the connection of the town with the famous diamond, which for centuries has been the pride of royalty and envy of many.

Historical accounts indicate that as a young boy, Duleep Singh -- the inheritor of the world's largest diamond and the last Sikh ruler of Punjab -- was kept in this hill town by the British for his education before he was taken to England to 'personally hand over' the diamond to Queen Victoria.

"Before he was taken to England in 1854, the young Sikh maharaja was brought to Mussoorie in 1852 and kept here for two years. He stayed at Whytbank castle in Barlowgunj which has long since been demolished and replaced by a five-star hotel," says local historian Gopal Bhardwaj.

Records indicate that the young prince was put in the care of Dr John Login, an army surgeon, and his wife Lena Login. The purpose of bringing the young prince to the hill town was to keep him away from Punjab and also to groom him before being taken to England.

At Mussoorie, the young maharaja engaged in a host of activities and showed keen interest in cricket and a cricket ground was especially made for him at Manor house, where St George's College is located today.

Later, in 1854 Dalhousie arranged for Singh to be taken to England, where he was shown the diamond and after examining it for a few minutes, he presented it to Queen Victoria.

"As the inheritor of the most sought-after diamond in the world, Duleep Singh was worked on so well by his English guardian to hand over the Kohinoor diamond that Dr Login was conferred a knighthood by the queen," says noted author and Mussoorie resident Bill Aitken.

A history

World-famous diamond Kohinoor inspires new and bloody history, Dec 24, 2016: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Kohinoor was probably first discovered during Mughal rule in India.

The Kohinoor is said to be cursed.

It has not been worn since death of Queen Victoria in 1901.

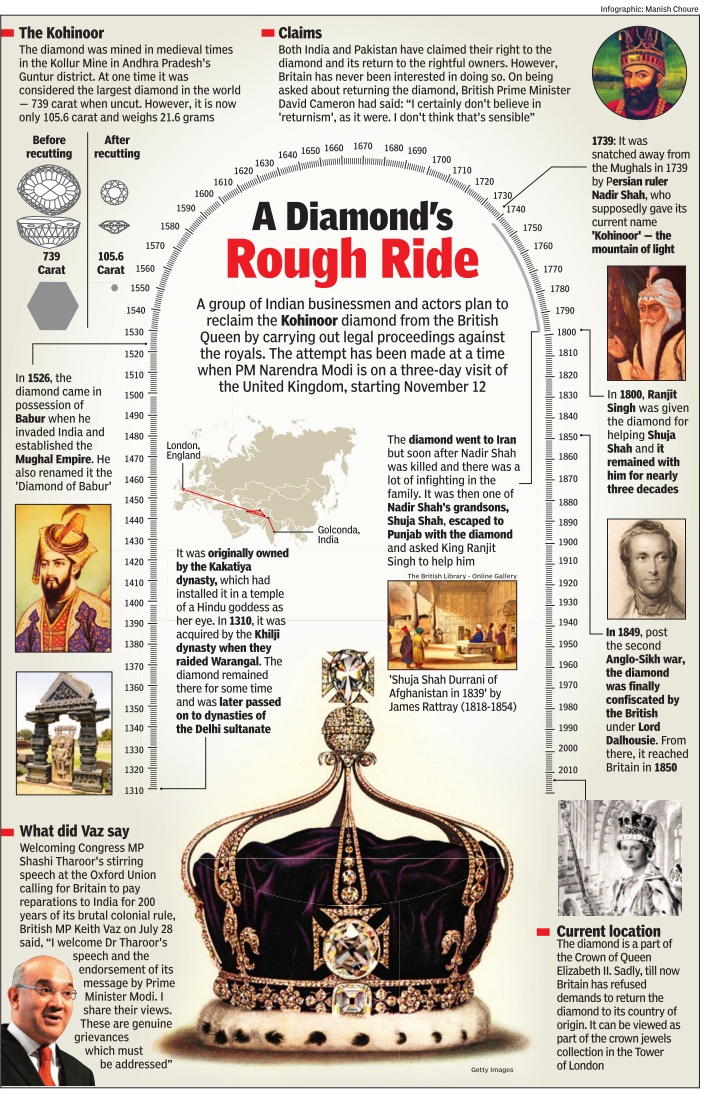

The Kohinoor was mined in medieval times in the Kollur mine in Andhra Pradesh's Guntur district.The Kohinoor was mined in medieval times in the Kollur mine in Andhra Pradesh's Guntur district.

Many precious stones have a blood-soaked history, but a new book reveals the world's most famous diamond the Kohinoor surpasses them all, with a litany of horrors that rivals "Game of Thrones".

The Kohinoor ("Mountain of Light"), now part of the British Crown Jewels, has witnessed the birth and the fall of empires across the Indian subcontinent, and remains the subject of a bitter ownership battle between Britain and India.

"It is an unbelievably violent story... Almost everyone who owns the diamond or touches it comes to a horribly sticky end," says British historian William Dalrymple, who co-authored "Kohinoor: The Story of the World's Most Infamous Diamond" with journalist Anita Anand. "We get poisonings, bludgeonings, someone gets their head beaten with bricks, lots of torture, one person blinded by a hot needle. There is a rich variety of horrors in this book," Dalrymple tells AFP in an interview.

In one particularly gruesome incident the book relates, molten lead is poured into the crown of a Persian prince to make him reveal the location of the diamond. Today the diamond, which historians say was probably first discovered in India during the reign of the Mughal dynasty, is on public display in the Tower of London, part of the crown of the late Queen Mother.

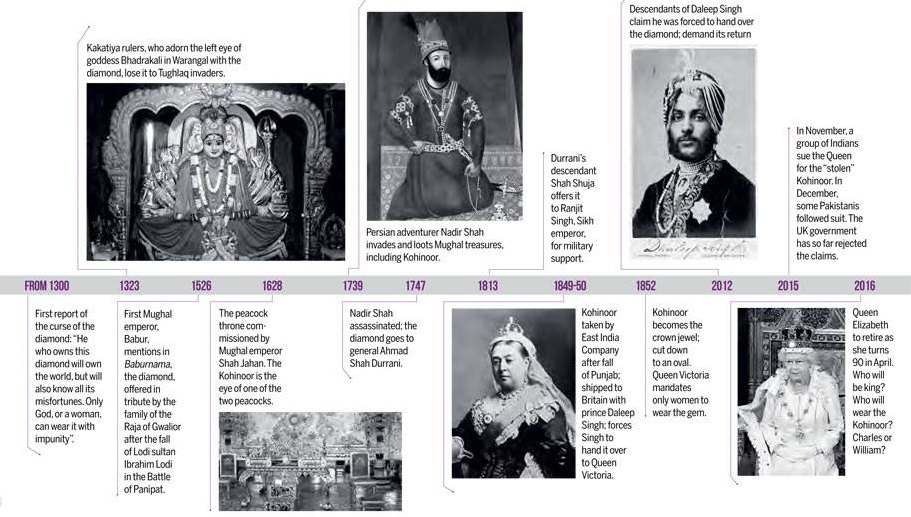

The first record of the Kohinoor dates back to around 1750, following Persian ruler Nader Shah's invasion of the Mughal capital Delhi. Shah plundered the city, taking treasures such as the mythical Peacock Throne, embellished with precious stones including the Kohinoor. "The Peacock Throne was the most lavish piece of furniture ever made. It cost four times the cost of the Taj Mahal and had all the better gems gathered by the Mughals from across India over generations," Dalrymple says.

The diamond itself was not particularly renowned at the time — the Mughals preferred coloured stones such as rubies to clear gems. Ironically given the diplomatic headaches it has since caused, it only won fame after it was acquired by the British.

"People only know about the Kohinoor because the British made so much fuss of it," says Dalrymple. India has tried in vain to get the stone back since winning independence in 1947, and the subject is frequently brought up when officials from the two countries meet. Iran, Pakistan and even the Afghan Taliban have also claimed the Kohinoor in the past, making it a political hot potato for the British government. Over the course of the century that followed the Mughals' downfall, the Kohinoor was used variously as a paperweight by a Muslim religious scholar and affixed to a glittering armband worn by a Sikh king.

It only passed into British hands in the middle of the nineteenth century, when Britain gained control of the Sikh empire of Punjab, now split between Pakistan and India. Sikh king Ranjit Singh had taken it from an Afghan ruler who had sought sanctuary in India and after he died in 1839 war broke out between the Sikhs and the British. Singh's 10-year-old heir handed over the diamond to the British as part of the peace treaty that ended the war and the gem was subsequently displayed at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London — acquiring immediate celebrity status. "It became, for the Victorians, a symbol of the conquest of India, just as today, for post-colonial Indians, it is a symbol of the colonial looting of India," Dalrymple says.

The Kohinoor, which is said to be cursed, has not been worn by a British monarch since the death of Queen Victoria in 1901. It last emerged from its glass case in the Tower of London for the funeral of the Queen Mother, when it was placed on her coffin.

Dalrymple: Kohinoor not gifted; Britons, Ranjit took it by force

The Times of India, May 01 2016

Kohinoor was no gift. British took it by force, and so did Ranjit Singh

Shah Shuja Durrani's autobiography is clear on how Ranjit Singh tortured his son to make him give up the diamond, writes William Dalrymple

Earlier this month Solicitor General Ranjit Kumar told the Supreme Court that the Kohi noor was given freely to the British in the mid-19th cen tury by Maharaja Ranjit Singh, and had been “neither stolen nor forcibly taken by British rulers“.

This was by any standards a strikingly unhistorical statement, all the odder because the facts of the case are not really in dispute. In truth, Ranjit Singh jealously guarded both his kingdom and his state jewels, and spent much of his adult life successfully keeping both from the grasping appetites of the militarised East India Company . By forming an alliance with the Company , but maintaining the most magnificent and up-to-date indigenous army of its day , he made sure that no Briton could enter the lands of the Khalsa without an invita tion. Distinguished visitors like Emily Eden were al lowed to see the Maharajah wearing the great jewel on his arm during state banquets, but when he died, he left the Kohinoor in his will not to the Company , nor to the British, nor even to Queen Victoria, but to the Jagannath temple at Puri.

The British got their hands on the jewel only a decade later, after taking advantage of the Sikh divisions and general anarchy which engulfed the Punjab following Ranjit's death. They finally defeated the Khalsa during a series of notably bloody battles in the Second Anglo-Sikh War of 1849. On March 29, 1849, the Kingdom of the Punjab was formally annexed by the Company, and the Last Treaty of Lahore was signed, officially ceding the Kohinoor to the Queen and the Maharaja's other assets to the Company .

Article III of the treaty read: “The gem called the Koh-i-Noor, which was taken from Shah Sooja ool-Moolk by Maharajah Runjeet Singh, shall be surrendered by the Maharajah of Lahore to the Queen of England.“ On December 7, 1849, in the presence of the Board of Administration for the affairs of the Punjab, Duleep Singh, the tenyear-old son of Ranjit Singh, was compelled to hand over the great diamond. So who should now own the Kohi noor? The case is often made in India that as the Kohinoor was taken by the British at the point of a bayonet, the British must therefore give it back. Yet the reality is more muddy. While the Kohinoor certainly originated in India, most probably in the Kollur mines of Golconda, Persia, Afghanistan and Pakistan also have good claims on the jewel, as it was owned at different times by Nadir Shah of Persia, Ahmed Shah Durrani of Afghanistan, and Ranjit Singh of Lahore. All three countries have at different times claimed the jewel and issued legal action in attempt to get it back.

Moreover, as the third article of the Treaty of Lahore hints, Ranjit Singh also took the jewel by force, just as the British did. In the same way that British sources tend to gloss over the violence inherent in their seizure of the stone, so Sikh ones do likewise. Yet the autobiography of its previous owner Shah Shuja Durrani, which I found in Kabul when I was working on my last book, Return of a King, is explicit about what happened.

On arrival in Lahore, to which he had been invited by Ranjit on his fall from power, Shuja was separated from his harem, put under house arrest and told to hand over the diamond: “The ladies of our harem were accommodated in another mansion, to which we had, most vexatiously, no access,“ wrote Shuja in his Memoirs.“Food and water rations were reduced or arbitrarily cut off.“

Slowly, Ranjit increased the pres sure. At the lowest ebb of his fortunes, Shuja was put in a cage, and according to his own account, his eldest son, Timur Shah, was tortured in front of him until he agreed to part with his most valuable possession. On June , 1813, Ranjit Singh was received by Shuja “with much dignity, and both being seated, a solemn silence ensued for nearly an hour. Ranjit then, getting impatient, whispered to one of his attendants to remind the Shah of the object of his coming. No answer was returned, but the Shah with his eyes made a signal to a eunuch, who retired, and brought in a small roll, which he set down on the carpet at an equal distance between the chiefs. Ranjit Singh desired his eunuch to unfold the roll, and when the diamond was recognized, the Sikh immediately retired with his prize in his hand.“

India's greatest diamonds -the Darya Nur, the Hope diamond, the Noor al-Ayn, the Orlov and Pitt-Regent diamond -all have exceptionally blood histories, with long litanies of betrayals, blindings, thefts, torture, assassination and murder associated with them. My personal view is that looking into the distant past, and attempting to right wrongs with claims for compensation and restitution, while understandable, is little more than a recipe for conflict and division.History everywhere is full of horrors and where should the accounts stop?

Should the British sue Norway for Viking raids and Italy for the gold looted by the Romans? Should the Sri Lankan governments sue India for the destruction of the cities of Polonnoruwa and Anuradhapura by the Cholas in 993, when they invaded Sri Lanka, sacked all the towns, plundered the stupas and destroyed all the temples? According the Culavamsa chronicle: The Cholas violently destroyed here and there all the monasteries, Like blood-sucking yakkhas they took all the treasures of Lanka.They took away all valuables in the treasure house of the King, They plundered what there was to plunder in vihara and the town.The golden image of the Master [Buddha], The two jewels which had been set as eyes in the Prince of Sages, All these they took.They deprived the Island of Lanka of her valuables, Leaving the splendid town in a state as if it had been plundered by yakkhas. Rather than lawsuits, I think money and time would be better spent on proper education in history for all concerned. History is more complex and muddled than most people realise. How many Indians are aware, for example, of the bloody punitive raids the Chola navy made on the cities of Java and Indonesia when the coastal ports were looted and burned down? The British in particular need to learn what they did to pre-Colonial peoples across the world. For the same empire which led to the huge enrichment of Britain, conversely, led to the impoverishment of much of the rest of the non-European world. India and China, which until then had dominated global manufacturing, were two of the biggest losers in this story, along with hundreds of thousands of enslaved sub-Saharan Africans sent off to work in the Plantations. Yet, astonishingly , most British people are by and large completely unaware of the many horrors of their imperial history as it does not appear on any history curriculum taught in British schools.

We cannot change what has happened in the past, but we can try to understand and to learn from past errors and to make sure the worst of them are not repeated. For as Edmund Burke, the greatest scourge of the East India Company rightly put it, “those who fail to learn from history are destined always to repeat it."

Anand & Dalrymple: About Kohinoor

Jason Overdorf , The Kohinoor did seem to leave havoc in its wake “India Today” 15/12/2016

Much that is known about the Kohinoor is myth, rumour or conjecture. The world's most infamous diamond, as authors William Dalrymple and Anita Anand describe it, is believed to come accompanied with a curse that condemns its owner to an early and often grisly demise. Before the Earl of Dalhousie extorted it from the Sikh Maharaja Duleep Singh and it made its way to Queen Victoria in 1851, it's thought to have numbered among the favourite baubles of Mughal emperor Babur. It's believed to have been plucked from the eye of a temple idol in Southern India by marauding Turks. And it's sometimes thought to be the legendary Syamantaka-a gem brought to earth when the sun god Surya removed it from a chain around his neck to bestow it on the Yadava king of Dwarka. Many think it's the largest or most valuable or at least the most beautiful diamond in the world. Yet many of those 'facts' are outright falsehoods, and few of the other stories that surround the Kohinoor can be verified, Anand and Dalrymple learned, even as they uncovered newly translated sources that deepen the sense of magic and bloody intrigue behind the diamond that once represented history's greatest conquest and now stands for its most infamous theft. In separate interviews excerpted below, they spoke with India Today's Jason Overdorf about their discoveries.

Overdorf: With William working on the early history of the Kohinoor and Anita covering its fate after the British finally defeated the Sikh empire in 1849, there's not a great deal of obvious crossover in this collaboration. How did you work together?

Anand: Right from the start, we were constantly pinging each other, saying, "William, I found this, this is amazing." And then he would say, "Look what I've just found from the Persian archive. Look at this translation." In that way, we were terribly in each other's business. Although there are two distinct halves, there are fingerprints of each of us on both.

Overdorf: The book is a bit of a historical detective story. What was the most surprising or interesting discovery that you made?

Dalrymple: There is, in fact, not a single reference to a diamond that is to a hundred per cent certainty the Kohinoor before 1750, which is very late. What's happened is that, retrospectively, because the Kohinoor's so famous, people assume that when a large diamond turns up in a Mughal source or another source that it must be the Kohinoor. We just don't know how the Mughals got the Kohinoor or where it came from. The probability is that it came from a Golconda mine; that seems almost certain, but you can't trace a diamond with crystallography. The strong possibility is that it's the stone referred to by Babur in the Baburnama, which Humayun took to Persia. All we know for certain, and the first reference to it is translated for the first time in this book, is that around 1740 Persian historian Muhammad Kazim Marvi says, "I saw the Kohinoor. It was at the head of one of the peacocks in the Peacock Throne." He saw it in Herat. All the great Mughal experts have known this, but I certainly hadn't.

Anand: I'm a journalist, not a historian, so I go looking for eyewitnesses. A European called John Martin Honigberger, who was there after the death of [Sikh Emperor] Ranjit Singh, was my eyewitness. He wrote about the committing of sati by the queens of Ranjit Singh. At first you hear his deep discomfort at the way in which these queens are burnt alive on the pyre of their husband, and then he sort of mentions in passing that these seven slave girls of Ranjit Singh are also burnt to death-but they're not even named. When you write such things, you just feel a little wiped out from the horror of it.

Overdorf: What was the most striking moment for you in the diamond's history?

Dalrymple: I think there are two incidents, just for the sheer mayhem that this diamond can cause wherever it goes. One is the story of Shah Rukh, the grandson of Nader Shah, who it turned out didn't have the Kohinoor, being tortured to surrender it. He has paste put on his head, and then they pour molten lead on him. It's just like the end of Daenerys Targaryen's brother in the first season of Game of Thrones. Then there's an extraordinary moment when the Medea takes the stone over to England in Anita's half of the book, and cholera breaks out on the ship. It's like another of my favorite movies, Werner Herzog's Nosferatu, when the plague ship arrives in Amsterdam and rats pour off it. The diamond does seem to leave havoc in its wake.

Overdorf: The book covers a great deal of Indian history. What makes the Kohinoor an effective lens through which to view the rise and fall of empires?

Anand: That's the kind of thing I'm interested in anyway: looking at one person and how history radiates out from that one person. With the Kohinoor, it is this pivotal point with history teetering around it. It is a stone that is surrounded by stories of blood, intrigue and murder. It has divided empires. It has pitted empires against each other. And even now if the Kohinoor is mentioned, you will have extraordinarily hot passions running. The British may have cut it to almost half of its size but it still retains all of its power.

Overdorf: Shashi Tharoor re-energised the debate over the question of its possible return to India last year. How do you feel about that question lying in the backdrop to the book?

Dalrymple: It becomes a symbol for colonial loot, a touchstone for the whole question of what do you do about colonial history. Do you try and right the wrongs of the past, or do you just say that history is bloody? There's no question that Ranjit Singh got the Kohinoor by torturing Shah Shuja's son. Shah Shuja's ancestor got it on the bloody night of Nader Shah's assassination. Nader Shah got it by defeating the Mughals. So the diamond, whether or not you believe in the existence of a curse, certainly has the ability to create discord and discontent and division wherever it goes. It could potentially be a major issue in British-Indian relations in the future.

Overdorf: As your book makes clear, India isn't the only country with a claim to the jewel, either.

Anand: I am as interested as everybody else to see what happens next. India wants it back, Pakistan wants it back, Iran has asked for it back, the Taliban has asked for it back. Whatever legal moves will be made, William and I have done a lot of the casework, if you like. Do I think the British will give it back? They have said many times, "Not on your nelly," which is a peculiar British expression that means "No way." They don't want to set a precedent for giving things back. Once they give the Kohinoor back, then the Greeks are going to immediately want their Elgin marbles back and any number of claimants will want other artefacts back. The museums of Great Britain will empty.

Legal position, government's stand: India

1956: Koh-i-noor, not a stolen object: Government

The Times of India, Apr 20 2016

`Nehru said no ground to claim Kohinoor back'

The government pointed out that the solicitor general's statement in court that the Kohinoor could not be categorised as a stolen object merely reflected the position that governments have consistently taken since 1956 when Jawaharlal Nehru was the PM.“Pandit Nehru went on record saying there was no ground to claim this art treasure back. He also added that efforts to get the Kohinoor back would lead to difficulties,“ the statement said.

In fact, the ministry quoted Nehru as having said, “To exploit our good relations with some country to obtain free gifts from it of valuable articles does not seem to be desirable. On the other hand, it does seem to be desirable that foreign museums should have Indian objects of art.“ The ministry also claimed that ever since Narendra Modi took over as the PM, several significant pieces of India's history -a 10th century statue of Goddess Durga from Germany , an over 900-year-old sculpture Parrot Lady from Canada, and antique statues of Hindu deities from Australian art galleries -were brought back.“None of these gestures affected India's relations with Canada, Germany or Australia,“ the ministry said.

The Akali Dal on Tuesday contested the government's take on Kohinoor and called for immediate review of its submission made before the Supreme Court on Monday. “What the government has said in the affidavit to the court is far from the truth as it is not possible for a 10-year-old Duleep Singh to have given it or gifted it, that too to the enemy , unless he was tricked or coerced into it by traitors in his advisory council,“ said SAD MP and spokesperson Prem Singh Chandumajra.

Koh-i-noor, not stolen: Centre to SC

The Times of India, Apr 19 2016

Kohinoor was gifted, not stolen, says Centre to SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra

India's hopes of getting the Kohinoor back may have ended as the Centre categorically told the Supreme Court on Monday that the famous diamond could not be viewed as a “stolen“ item, spirited away by avaricious colonial rulers.

The Centre's stand will disappoint many who believe the British tricked Sikh ruler Duleep Singh into parting with the Kohinoor that historically belonged to India and should legitimately be brought back.

A bench of Chief Justice T S Thakur and Justice U U Lalit, however, said though the Centre indicated the futility of entertaining a PIL seeking a direction to facilitate return of “stolen“ precious items from India, it could not simply dismiss the plea as it could im pede future efforts to reclaim precious items and artefacts.

“If we were to dismiss the petition, it could stand in the way of the government's future efforts. The countries possessing items taken from India could well cite the Supreme Court's order to reject claims for return of the treasure items in future,“ the bench said. Solicitor general Ranjit Kumar said he would take instructions from the ministry of external affairs on this issue and file an affidavit in six weeks specifying the government's stand on return of Kohinoor and other precious items taken out of the country . Responding to a PIL filed by NGO `All India Human Rights and Social Justice Front' seeking a direction to the Front' seeking a direction to the Centre to bring back the diamond and other precious artefacts taken by the British during colonial rule, the SG narrated a brief history of Kohinoor from the time it was found in the Kollur mines in present day Guntur, Andhra Pradesh.

“It changed hands several times till Shah Shuja of Afghanistan gave it to Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1813. After his death, his successor Duleep Singh gave it to the British as compensation for the AngloSikh war. The East India Company gifted it to Queen Victoria in 1849 and since then it has been in possession of the British royalty ,“ he said.

“India's first PM Jawaharlal Nehru in 1956 had written a letter to the British government. A number of times, the matter was raised in LS. But Kohinoor cannot be categorised as an item stolen and taken out of the country ,“ the SG said. Indicating the futility of the exercise, the SG told the SC that seeking return of the precious stone was fraught as there could be similar demands from other countries.

The bench was not impressed.“India was colonised and ruled by several foreign powers. Is there a case where India has looted other countries and brought back treasures from there?“ it said, asking the SG to keep all dimensions in mind and take specific instructions from various ministries before filing the affidavit.

2018/ Kohinoor surrendered to British: ASI

Nidhi Bhardwaj, October 16, 2018: The Times of India

In April 2016, the government had told the Supreme Court that the Kohinoor diamond was neither “forcibly taken nor stolen” by the British. The government had stated that it was gifted to the East India Company by the successors of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who ruled Punjab at the time.

The Archeological Survey of India (ASI), however, has contradicted the government’s stand by stating in a recent RTI reply that the diamond was in fact “surrendered” by the Maharaja of Lahore to Queen Victoria of England. In its response to a PIL, the government had said that Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s kin had given the Kohinoor to the British as “voluntary compensation” to cover the expenses of the Anglo-Sikh War.

Activist Rohit Sabharwal had filed a RTI query seeking information showing the grounds on which the Kohinoor was transferred to the UK. “I had no clue who to approach with my RTI application, so I forward it to the Prime Minister’s office (PMO). It was the PMO that sent it to ASI. The RTI Act allows a public authority to transfer an application to another another authority which has the information sought,” said Sabharwal.

In the RTI query, he also asked if it was a gift to the UK by the Indian authorities or if there was any other reason for the transfer. The ASI replied, “As per the records, the Lahore Treaty held between Lord Dalhousie and Maharaja Duleep Singh in 1849, the Kohinoor diamond was surrendered by the Maharaja of Lahore to the Queen of England.”

The reply gives an extract of the treaty which reads, “The gem called Kohinoor which was taken from the Shah-Suja-Ul-Mulk by Maharaja Ranjeet Singh shall be surrendered by the Maharaja of Lahore to the Queen of England.” According to the reply, the treaty indicates that “the Kohinoor was not handed over to the British on the wishes of Duleep Singh. Moreover, Duleep Singh was a minor at the time of the treaty”.

“I recently met a British national who claimed that the Kohinoor was gifted to the queen. Since that day, I decided to go deep into the subject.” The chairman of the Maharaja Duleep Singh Memorial Trust, Kothi Bassian and poet Gurbhajan Singh Gill said this is exactly what they had been saying for many years – that the diamond was taken away by the British from Maharaja Duleep Singh when he was only nine.

SC: dismisses repatriation, different CJIs’ perceptions

Year-long proceeding in the Supreme Court on PILs seeking repatriation of the Kohinoor diamond from the UK exemplified how parameters of judicial scrutiny are directly linked to a judge's individual perception, which many feel is the reason for asymmetric judicial pronouncements in similar cases.

On April 8 in 2016, a bench headed by then CJI T S Thakur had asked the Centre to examine a PIL seeking recovery from the UK of all precious items taken by the British from India, including the famous Kohinoor, statues and artefacts. The then UK PM had made a statement that if the UK was to honour claims of other countries on artefacts, then its museums would soon become empty. On April 18 last year, the Centre had disappointed many who believed that the British tricked Sikh ruler Du leep Singh to part with the Kohinoor, which belonged to India and should legitimately be brought back, by saying the prized diamond could not be categorised as a “stolen“ item.

The bench headed by CJI Thakur had said it could not simply dismiss the petition as it could impede future efforts to reclaim these precious items and artefacts. “If we were to dismiss the petition, it could stand in the way of the government's future efforts. The countries possessing the items taken from India could well cite the SC's order to reject claims for return of the treasure items in future,“ it had said.

But Friday presented a contrasting scene. A bench headed by CJI J S Khehar expressed surprise over how these PILs ever came to be entertained.“This is quite surprising. How can any Indian court pass order on a property which was with the UK for centuries.These are all misconceived petitions. Can we pass an order asking the UK not to auction the diamond?“ he asked.

The bench said the Centre had filed an affidavit saying it would continue to explore ways and means for resolution of this issue through diplomatic process with the UK government. When a petitioner's counsel said the court should monitor the government's efforts to get the Kohinoor back, the bench curtly responded, “Diplomatic measures can never be under supervision of judiciary .“ The bench dismissed both petitions.

The British stand

As in 2023

NAOMI CANTON, June 3, 2023: The Times of India

A new exhibition at the Tower of London — backed by Buckingham Palace — about the crown jewels, which opened to directly follow the coronation of King Charles, states that the Kohinoor was “taken by” the East India Company and that Maharaja Duleep Singh was “compelled” to surrender it.

The new permanent Crown Jewels exhibition at the Tower of London, which opened on May 26, features an “origins room” which for the first time tells the history of a number of items in the Royal Collection, including the 105. 6 carat diamond which it describes as a“symbol of conquest”. “The Kohinoor diamond has had many previous owners, including Mughal Emperors, Shahs of Iran, Emirs of Afghanistan, and Sikh Maharajas,” the label in the origins room states. “The 1849 Treaty of Lahore compelled 10-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh to surrender it to Queen Victoria, along with control of the Punjab. ”

A separate piece of new text about the Kohinoor on the Crown Jewels website states: “The East India Company took the jewel from deposed Maharaja Duleep Singh in 1849, as a condition of the Treaty of Lahore. ” The Crown Jewelsexhibition also features a film about the Kohinoor which “goes through its history using a graphic map. It shows where it was supposedly mined (the Golconda mines). . . . There is an image of Duleep Singh handing it over,” a spokesperson for Historic Royal Palaces said. Text overlay on the film states: “Taken by the East India Company. ” The label accompanying the Kohinoor, which is set in the Queen Mother’s Crown, has also changed. Now it describes it as a “symbol of conquest”.

“The Royal Collection Trust have approved the new wording,” the spokesperson told TOI. The transparency comes after Buckingham Palace announced that Queen Camilla would not be crowned with the Queen Mother Crown — set with the Kohinoor —at her coronation. She instead wore Queen Mary’s Crown.

Legal proceedings in UK

The Times of India, Nov 09 2015

The world famous Kohi-noor diamond

Elizabeth II may face legal challenge over Koh-i-noor

The 105-carat stone, believed to have been mined in India nearly 800 years ago, was presented to Queen Victoria during the Raj and is now set in a crown belonging to the Queen’s mother on public display in the Tower of London.

David de Souza, co-founder of the Indian leisure group Titos, is helping to fund the new legal action and has instructed British lawyers to begin high court proceedings.

The Koh-i-Noor, which means “mountain of light”, was once the largest cut diamond in the world and had been passed down from one ruling dynasty to another in India.

But after the British colonisation of the Punjab in 1849, the Marquess of Dalhousie, the British governor-general, arranged for it to be presented to Queen Victoria. The last Sikh ruler, Duleep Singh, a 13-year old boy, was made to travel to Britain in 1850 when he handed the gem to Queen Victoria.

Kohinoor's Kashmir connection

The Times of India, April 22, 2016

Advocating a diamond's human rights sounds as believable as 7-yearold Duleep Singh handing over the Kohinoor on his own rather than acceding to the domineering grownups around him.

Those adults included officials of the East India Company--victor of the First AngloSikh War--and a regency council stacked with machinating Sikh nobles. And on their agenda was war indemnities imposed on the Sikh Empire and its ruler, via the 1846 Treaty of Lahore. A subsequent Treaty of Amritsar was also signed to ensure the vanquished paid up and the Kohinoor, sent to Queen Victoria in 1850, was just part of the package. Among other items of the Sikh state on the block was “all the mountainous country with its dependencies situated to the eastward of the River Indus and the westward of the River Ravi including Chamba and excluding Lahul, being part of the territories ceded to the British government by the Lahore State according to the provisions of Article IV of the Treaty of Lahore, dated 9th March, 1846.“ That included Kashmir.

Serendipitously , the Dogra ruler of Jammu, Gulab Singh was only too willing to buy it.

Once he paid 75 lakh Nanakshahi rupees to the British, he officially became the Maharaja of J&K. Er go, the same treaties that saw the Kohinoor pass into Com pany hands and thence the British crown, also saw a Dogra become ruler of Kashmir. The “human rights“ and “social justice“ implications suddenly become clearer.If India ever challenges the British right to one coveted Kword, India's own right to the other coveted K-word--gained by the Instrument of Accession signed in 1947 by Gulab Singh's descendant--could also become shaky indeed. No wonder PM Jawaharlal Nehru warned way back in 1956 that trying to reclaim the Kohinoor “would lead to difficulties“. Hopefully the government won't fumble on this fact too.

See also

Kohinoor/ Koh-i-Noor