Kerala: Society, demography

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Migrant population

As in 2019

Shenoy Karun, May 2, 2019: The Times of India

From: Shenoy Karun, May 2, 2019: The Times of India

In parts of Kerala, Nirahua is bigger star than Mammootty

Migrants From Bengal, Bihar And Odisha Are Powering The Economy, But They’re Also Changing Social, Cultural Dynamics

Outside a tiny ticket window at a movie theatre in Perumbavoor, the crowd makes a beeline for cheap tickets, selling at Rs 40 each. But the crowd has come not to watch Mammootty but Nirahua. In swathes of Kerala of late, Bhojpuri, Bangla and Odia films are as ubiquitous as are conversations conducted in Hindi in malls, restaurants and auto-rickshaws.

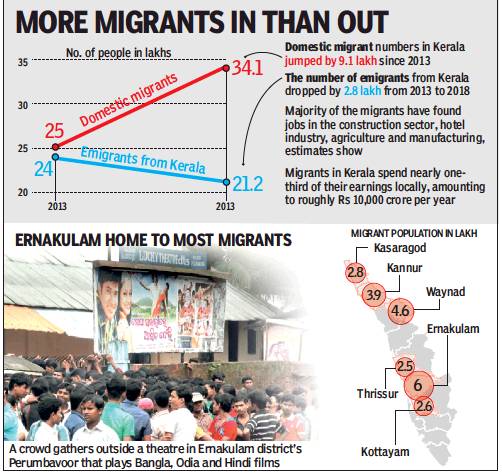

As the sheen on Kerala’s Gulf dream continues to fade, the state finds itself caught in another wave of migration. While the number of Malayali emigrants has continued to decline in the past few years, the number of workers from other states pouring into Kerala has increased manifold. A look at the data lifts the lid on this mass manpower movement that is likely to have far reaching implications for Kerala’s society and labour force.

The Kerala Migration Survey 2018, by the Centre for Development Studies in January, found the number of emigrants from Kerala had dropped from 24 lakh in 2013 to 21.2 lakh in 2018. This comes even as the state government-owned Gulati Institute of Finance and Taxation (GIFT), estimates that domestic migrant numbers in Kerala have jumped from 25 lakh in 2013 to 34.1 lakh in 2018. D Narayana, director of GIFT, said the number of migrants from other states in Kerala has been growing annually by an estimated 1.8 lakh on average since 2013. In contrast, the Kerala Migration Survey found that the number of emigrants has fallen by over 3 lakh between 2013 and 2018. According to a 2018 state government report, the highest number of migrants in Kerala are in Ernakulam district (6 lakh), followed by Wayanad (4.6 lakh), Kannur (3.9 lakh), Kasaragod (2.8 lakh), Kottayam (2.6 lakh) and Thrissur (2.5 lakh). While 18% of the migrants in Kerala are skilled labourers, 69% are unskilled labourers. Majority of the migrants have found jobs in the construction sector, hotel industry, agriculture and manufacturing. Today, migrants are major drivers of the economy in Perumbavoor, a small town located at the banks of Periyar in-Ernakulam district. In fact, there is an entire market now called ‘Bhai Bazaar’ in Perumbavoor where migrants sell wares of all kinds on Sundays. Kerala finance minister Thomas Isaac said that high inflow of migrants from other states and the return of Malayali emigrants is bound to have an impact on the entire state’s economy. The large number of migrants in Kerala has put the state on the brink of change. Ali KM, chairman of the standing committee for welfare, Perumbavoor Municipal Corporation, says, “First, it was the buses running between Perumbavoor and nearby towns like Kochi or Angamaly that started displaying signs in Hindi. Then came the grocery shops with placards in Bengali and Hindi. But I think the assimilation of migrants in Kerala was complete when cultural milestones were touched, somewhere in the early 2000s, when local theatres started showing Bangla, Bollywood and Odia movies and restaurants started dishing out cuisines from these states.”

Near the high court building in Kochi, 47-year-old Ansar Ahmed runs a tyre repair shop. He hails from Majouli Chowk Masjid in Bihar’s Vaishali district.

“I was working as a tailor in Nepal when some of my friends in Mumbai were hired by a local supermarket owner from Kochi. I came here 24 years ago and ran a small tailoring shop for eight years making embroidery on clothes for wholesalers. Then they started using computer-aided design and I found myself jobless in 2008. I went back to Bihar, learned how to repair tyres from my brother-in-law and started a shop here in 2011,” Ahmed said. As luck would have it, Ahmed met a local woman named Rahiyanath, also a tailor, and they eventually married. “My children can speak Hindi and Malyalam with equal finesse. I helped my brother and his family and some of his relatives settle in Kochi. They also run tyre repair shops here,” he said. Some like Humayun Kabir, who has spent a decade in Kerala after migrating from West Bengal, have taken up two jobs to earn more. Kabir works in the construction industry in Perumbavoor throughout the week but sells beedis made in Murshidabad, Bengal, at Bhai Bazaar on Sundays. A few metres from Kabir’s stall, Yuraij Yousuf sells clothes at throwaway prices. From Monday to Saturday, Yousuf repairs computers.

In 2013, workers from West Bengal made up 20% of all migrant labourers in Kerala followed by Bihar (18.1%), Assam (17.3%), Uttar Pradesh (14.8%) and Odisha (6.7%), according to GIFT.

Benoy Peter, executive director at Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development, said between 1961 and 1991, workers from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka made up most of the migrant bluecollar workers. “Migration from other states picked up in the 1990s as people found jobs in the timber industry hubs like Perumbavoor. Around the same time, Supreme Court banned forest-based plywood industry in Assam. Workers from Assam migrated to Perumbavoor to work in plywood manufacturing. Even today, the experts in plywood manufacturing here are all from Assam,” Peter said.

“The migrants not only help run the economy, they also spend nearly one-third of their income locally. That amounts to roughly Rs 10,000 crore every year,” he added. Peter says that it’s common for Malayali children to be studying alongside students from states like West Bengal, UP, Bihar and stray Hindi or Bengali words can often be heard in classrooms. Driving the labour migration to Kerala is the lure of higher daily wages, says Peter. Local wages in Kerala are more than double that in other states. Take this: Agricultural labourers in Kerala make Rs 648 a day on average while nonagricultural labourers can get up to Rs 615 daily, according to data released by the Labour Bureau of Government of India in 2016. The average daily wage rate for agricultural labourers is Rs 245 in West Bengal, Rs 230 in Assam, Rs 216 in UP, Rs 210 in Bihar and Rs 207 in Odisha. The average daily wage rate for nonagricultural labourers is also well below Rs 300 in all these states.

Remittances sent back by migrant workers in Kerala have allowed families back home to send children to school and build ‘pucca houses’ among other things. According to Peter, many migrant labourers have worked in Kerala for a few decades and returned to “retire” in their native states. Peter says that during a trip to West Bengal in 2017, he came across several people who had worked in Kerala at some point in their lives and were familiar with remote places in Ernakulamdistrict like Allapra, Pulluvazhi or Malamuri, all of them near Perumbavoor.