Kangra District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Kangra District

Physical aspects

North-easternmost District of the Jullundur Division, Punjab, lying between 31 degree 21' and 32 degree 59' N. and 75 degree 37' and 78 degree 42' E., with an estimated area of 9,978 square miles. It is bounded on the north-west by Chamba State ; on the north by Kash mlr territory ; on the east by Tibet ; on the south-east by Bashahr State ; on the south by the Kotgarh villages of Simla District, and by the States of Kumharsain, Sangri, Suket, Mandl, and Bilaspur; on the south-west by the District of Hoshiarpur ; and on the west by Gurdas- pur. It stretches eastwards from the plains of the Bari and Jullundur Doabs across the Himalayan ranges to the borders of Tibet, and com- prises two distinct tracts which lie on either side of the Outer Hima- layas and present very diverse natural features. Of these two tracts the western block, which constitutes Kangra proper, is described in this article.

This portion, which lies south of the Dhaola asoects Dhar range of the Outer Himalayas, consists of an irregular triangle, whose base lies upon the Hoshiar- pur border, while the Native States of Chamba and Mand! constrict its upper portion to a narrow neck, known as Bangahal, at one point less than 10 miles in width. Beyond this, the eastern block expands once more like an hour-glass, and embraces the Kulu subdivision, which comprises the tahals of Kulu and Saraj and the mid-Himalayan cantons of Lahul and Spiti, each of which merits separate description. Of the total estimated area of 9,978 square miles, 2,939 are in Kangra proper. This is the more important part of the District as regards population and cultivation, and comprises two wide and fertile valleys.

The Kangra valley lies between the Dhaola Dhar and the long irregular mass of lower hills which run, almost parallel to the Dhaola Dhar, from north-west to south-south-east. The second valley runs between these hills and the Sola Singhi range, and thus lies parallel to the Kangra valley. On the north-west the District includes the outlying spurs which form the northern continuation of the Sola Singhi, running down to the banks of the Beas and Chakki, and it also embraces the western slopes of that range to the south. The Kangra valley is famous for its beauty, the charm lying not so much in the rich cultivation and perpetual verdure of the valley itself as in the con- stant yet ever-changing view of the Dhaola Dhar, whose snowy peaks rise sheer above the valley, sometimes to 13,000 feet, and present a different phase of beauty at each turn in the road.

The of Bangahal forms the connecting link between Kangra proper and Kulu, and is divided by the Dhaola Dhar into two parts : to the north Bara or Greater Bangahal, and to the south Chhota or Lesser Bangahal.

Although the general trend of the three main ranges which enclose the valleys of Kangra proper is from north-west to south-east-by-south, its one great river, the Beas, flows through this part of the District from east to west. Entering the centre of its eastern border at the southern head of the Kangra valley, it runs past Sujinpur Tlra in a narrow gorge through the central mass of hills, flowing westwards with a southerly trend as far as Nadaun.

Thence it turns sharply to the north-west, flowing through the valley past Dera Gopipur ; and gradually winding westward, it passes between the northern slopes of the Sola Singhi range and the hills forming its continuation to the north. The remainder of the District is singularly devoid of great streams. The Kangra valley is drained by several torrents into the Beas, the principal of these flowing in deep gorges through the central hills.

All three fades of the stratified rocks of the Himalayas are to be found. To the north, in Spiti, the Tibetan zone is represented by a series of beds extending in age from Cambrian to Cretaceous ; this is separated from the central zone by the granite range between Spiti and Kulu. The rocks of the central zone consist of slates, conglomerate, and limestone, representing the infra-Blaini and overlying systems of the Simla area. Still farther to the south the third or sub-Himalayan zone consists of shales and sandstones (Sirmur series) of Lower Tertiary age, and sandstones and conglomerates belonging to the Upper Tertiary Siwalik series. The slate or quartz-mica-schist of the central zone is fissile, and of considerable value for roofing purposes; it is quarried at and round Kanhiara. Gypsum occurs in large quantity in Lower Spiti .

The main valley is the chief Siwalik tract in the Province, but its flora is unfortunately little known. An important feature is the exis- tence of considerable forests of the chir (Pinus longifolia), at compara- tively low elevations. Kulu (or the upper valley of the Beas) has a rich temperate flora at the higher elevations; in the lower valleys and

1 Medlicott, 'The Sub-Himalayan Ranges between the Ganges and Ravi,' Memoirs, Geological Survey of Iiulia, vol. iii, part ii; Stoliczka, 'Sections across the North- West Himalayas; Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vol. v, part i ; Hay den, ' Geology of Spiti,' Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vol. xxxvi, part i. in Outer Saraj (on the right bank of the Sutlej) the vegetation is largely sub-tropical, with a considerable western element, including Clematis orientalis, a wild olive, &c. The flora of British Lahul, the Chandra - Bhaga or Chenab valley, and Spiti, are entirely Tibetan.

The forests of Kangra District used to abound in game of all descriptions ; and of the larger animals, leopards, bears, hyenas, wolves, and various kinds of deer are still fairly common. Tigers visit the District occasionally, but are not indigenous to these hills. The ibex is found in Lahul, Spiti, Kulu, and Bara Bangahal ; and the musk deer in Kulu and on the slopes of the Dhaola Dhar. The wild hog is common in many forests in the lower ranges. Of smaller quadrupeds, the badger, porcupine, pangolin, and otter are commonly found. Different species of wild cat, the flying squirrel, hare, and marmot abound in the hills.

The bird-life of both hill and plain is richly represented ; and, though game is not very abundant, many species are found. These include several varieties of pheasant, among them the monal and argus, the white-crested pheasant, and the red jungle-fowl which is common in the lower valleys. Of partridges many species are found, from the common grey partridge of the plains to the snow partridge of the Upper Himalayas. Quail and snipe sometimes visit the District in considerable numbers. Ducks, geese, and other water- birds are seen upon the Beas at the beginning and end of summer. Fishing is not carried on to any great extent. Thirty-six fisheries are leased to contractors, mostly on the Beas, only a few being in the lower parts of the hill torrents.

The mean temperature at Kangra town is returned as 53 in winter, 70 in spring, 8o° in summer, and 68° in autumn. The temperature of the southern portion of Kangra proper is much higher than this, while that of the inhabited parts of the Dhaola Dhar is about 8° lower. Endemic diseases include fever and goitre. The widespread cultivation of rice, by which the whole Kangra valley is converted into a swamp, has a very prejudicial effect upon health.

The rainfall varies remarkably in different parts. The average annual fall exceeds 70 inches ; along the side of the Dhaola Dhar it amounts to over 100 ; while 10 miles off it falls to about 70, and in the southern parts to about 50. Bara Bangahal, which is on the north side of the Dhaola Dhar, has a climate of its own. The clouds exhaust themselves on the south side of the great range ; and two or three weeks of mist and drizzle represent the monsoon. The rainfall in Kulu is similarly much less than that of Kangra proper, averaging from 30 to 40 inches, while Lfihul and Spiti are almost rainless.

A disastrous earthquake occurred on April 4, 1905. About 20,000

human beings perished, the loss of life being heaviest in the Kangra

and Palampur tahsils. The station of Dharmsala and the town of

Kangra were destroyed. The fort and temples at Kangra received

irreparable damage, and many other buildings of archaeological interest

were more or less injured.

History

The hills of Kangra proper have formed for many centuries the dominions of numerous petty princes, all of whom traced their descent from the ancient Katoch (Rajput) kings of Jullundur. According to the mythical chronology of the Maha- 8

bharata, this dynasty first established itself in the country between the

Sutlej and the Beas 1,500 years before the Christian era. In the

seventh century a.d., Hiuen Tsiang, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim,

found the Jullundur monarchy still undivided. At some later period,

perhaps that of the Muhammadan invasion, the Katoch princes were

driven into the hills, where Kangra already existed as one of their chief

fortresses; and their restricted dominions appear afterwards to have

fallen asunder into several minor principalities. Of these, Nurpur, Siba,

Goler, Bangahal, and Kangra are included in Kangra proper. In spite

of constant invasions, the little Hindu kingdoms, secure within their

Himalayan glens, long held out against the aggressive Muhammadan

power. In 1009 the riches of the Nagarkot temple attracted the

attention of Mahmfld of Ghazni, who defeated the Hindu princes at

Peshawar, seized the fort of Kangra, and plundered the shrine of an

immense booty in gold, silver, and jewels.

But thirty-five years later

the mountaineers rose against the Muhammadan garrison, besieged and

retook the fort, with the assistance of the Raja of Delhi, and set up

a facsimile of the image which Mahmud had carried away. From this

time Kangra does not reappear in general history till 1360, when the

emperor Flroz Tughlak again led a force against it. The Raja gave in

his submission, and was permitted to retain his dominions ; but the

Muhammadans once more plundered the temple, and dispatched the

famous image to Mecca, where it was cast upon the high road to be

trodden under the feet of the faithful.

Two hundred years later, in 1556, Akbar commanded in person an

expedition into the hills, and succeeded in permanently occupying the

fort of Kangra. The fruitful valley became an imperial demesne, and

only the barren hills remained in the possession of the native chiefs.

In the graphic language of Akbar's famous minister, Todar Mai, * he

cut off the meat and left the bones.' Yet the remoteness of the

imperial capital and the natural strength of the mountain fastnesses

encouraged the Rajput princes to rebel ; and it was not until after the

imperial forces had been twice repulsed that the fort of Kangra was

starved into surrender to an army commanded by prince Khurram in

person (1620). On the last occasion twenty-two chieftains promised

obedience and tribute, and agreed to send hostages to Agra. At one

time Jahanglr intended to build a summer residence in the valley, and

the site of the proposed palace is still pointed out in the lands of the

village of Gargari. Probably the superior attractions of Kashmir, which

the emperor shortly afterwards visited, led to the abandonment of his

design.

At the accession of Shah Jahan the hill Rajas had quietly settled down into the position of tributaries, and the commands of the emperor were received and executed with ready obedience. Letters patent (sanads) are still extant, issued between the reigns of Akbar and Aurangzeb, appointing individuals to various judicial and revenue offices, such as that of kdzl, kanungo, or chaudhri. In some instances the present representatives of the family continue to enjoy privileges and powers conferred on their ancestors by the Mughal emperors, the honorary appellation being retained even where the duties have become obsolete.

During the period of Muhammadan ascendancy the hill princes appear on the whole to have been treated liberally. They still enjoyed a considerable share of power, and ruled unmolested over the extensive tracts which remained to them. They built forts, waged war upon each other, and wielded the functions of petty sovereigns. On the demise of a chief, his successor paid the fees of investiture, and received a confirmation of his title, with an honorary dress from Agra or Delhi. The loyalty of the hill Rajas appears to have won the favour and confidence of their conquerors, and they were frequently deputed on hazardous expeditions, and appointed to places of high trust in the service of the empire.

Thus in the time of Shah Jahan (1646), Jagat Chand, Raja of Nurpur, at the head of 14,000 Rajputs, raised in his own country, conducted a most difficult but successful enterprise against the Uzbeks of Balkh and Badakhshan. Again, in the early part of the reign of Aurangzeb (1661), Raja Mandhata, grandson of Jagat Chand, was deputed to the charge of Bamian and Ghorband on the western frontier of the Mughal empire, eight days' journey beyond the city of Kabul. Twenty years later he was a second time appointed to this honourable post, and created a mansabddr of 2,000 horse. In later days (1758), Raja Ghamand Chand of Kangra was appointed governor of the Jullundur Dc&b and the hill country between the Sutlej and the Ravi.

In 1752 the Katoch principalities nominally formed part of the territories ceded to Ahmad Shah Durrani by the declining Delhi court. But the native chieftains, emboldened by the prevailing anarchy, resumed their practical independence, and left little to the Durrani monarch or the deputy who still held the isolated fort of Kangra for the Mughal empire.

In 1774 the Sikh chieftain, Jai Singh, obtained the fort by stratagem, but relinquished it in 1785 to Sansar Chand, the legitimate Rajput prince of Kangra, to whom the State was thus restored about two centuries after its occupation by Akbar. This prince, by his vigorous measures, made himself supreme throughout the whole Katoch country, and levied tribute from his fellow chieftains in all the neighbouring States. Every year, on fixed occasions, these princes were obliged to attend his court, and to accompany him with their contingents wherever he undertook a military expedition. For twenty years he reigned supreme throughout these hills, and raised his name to a height of renown never attained by any ancestor of his race. He found himself unable, however, to cope with the Sikhs, and two descents upon the Sikh possessions in the plains, in 1803 and 1804, were repelled by Ran jit Singh.

In 1805 Sansar Chand attacked the hill State of Bilaspur (Kahlur), which called in the dangerous aid of the Gurkhas, already masters of the wide tract between the Gogra and the Sutlej. The Gurkhas responded by crossing the latter river and attacking the Katochs at Mahal Mori, in May, 1806. The invaders gained a complete victory, overran a large part of the hill country of Kangra, and kept up a constant warfare with the Rajput chieftains who still retained the remainder. The people fled as refugees to the plains, while the minor princes aggravated the general disorder by acts of anarchy on their own account The horrors of the Gurkha invasion still burn in the memories of the people. The country ran with blood, not a blade of cultivation was to be seen, and grass grew and tigers whelped in the streets of the deserted towns.

At length, after three years of anarchy, Sansar Chand determined to invoke the assistance of the Sikhs. Ranjit Singh, always ready to seize upon every opportunity for aggression, entered Kangra and gave battle to the Gurkhas in August, 1809. After a long and furious contest, the Maharaja was successful, and the Gurkhas abandoned their conquests beyond the Sutlej. Ranjit Singh at first guaranteed to Sansar Chand the posses- sion of all his dominions except the fort of Kangra and 66 villages, allotted for the support of the garrison ; but he gradually made encroachments upon all the hill chieftains. Sansar Chand died in 1824, an obsequious tributary of Lahore. His son, Anrudh Chand, succeeded him, but after a reign of four years abandoned his throne, and retired to Hardwar, rather than submit to a demand from Ranjit Singh for the hand of his sister in marriage to a son of the Sikh minister Dhian Singh. Immediately after Anrudh's flight in 1828, Ranjit Singh attached the whole of his territory, and the last portion of the once powerful Kangra State came finally into the possession of the Sikhs.

Kangra passed to the British at the end of the first Sikh War in 1846, but the commandant of the fort held out for some time on his own account. When the Multan insurrection broke out in April, 1848, emissaries from the plains incited the hill chieftains to revolt ; and at the end of August in. the same year, Ram Singh, a Pathania Rajput, collected a band of adventurers and threw himself into the fort of Shahpur.

Shortly afterwards, the Katoch chief rebelled in the eastern

extremity of the District, and was soon followed by the Rajas of Jaswan

and Datarpur, and the Sikh priest, Bedi Bikrama Singh. The revolt,

however, was speedily suppressed ; and after the victory of Gujrtt, the

insurgent chiefs received sentence of banishment to Almora, while

Kangra subsided quietly into a British District. After the outbreak

of the Mutiny in 1857, some disturbances took place in the Kulu

subdivision ; but the vigorous measures of precaution adopted by the

local authorities, and the summary execution of the six ringleaders and

imprisonment of others on the occasion of the first overt act of rebel-

lion, effectually subdued any tendency to lawlessness. The disarming

of the native troops in the forts of Kangra and NQrpur was effected

quietly and without opposition. Nothing has since occurred to disturb

the peace of the District.

Few Districts are richer in antiquities than Kangra, The inscription* at Pathyar is assigned to the third century B.C., and that at Kan- hiara to the second century a. d. It is impossible to fix the date of the famous fort at Kangra Town. A temple in it was plundered by Mahmftd of Ghazni in 1009, and an imperfectly legible rock-inscrip- tion, formerly outside one of the gates of the fort and now in the Lahore Museum, is assigned to a period at least 400 years earlier. The small temple of Indreswara at Kangra dates from about the ninth century. The beautiful shrine of Baijnath at Kiragrama was formerly attributed to the same period, but recent investigations point to a date three or four centuries later. The present temple of Bajreswari Devi at Bhawan, a suburb of Kangra, is a modern structure, but it conceals the remains of an earlier building, supposed to date from 1440. It has acquired a repute, to which it is not entitled, as the successor of the temple that was sacked by Mahmud. Remains found at Kangra prove that it was once a considerable Jain centre. The fort at Nurpur, built in the sixteenth and seventeenth cen- turies, contains a curious wooden temple; and in 1886 a temple of much earlier date, with sculptures unlike anything hitherto found in the Punjab, was unearthed.

At Masrur, in the Dehra tahsil, are some rock-temples of uncertain date. In the Kulu valley, the princi- pal objects of antiquarian interest are the temples of Bajaura. One of them, probably the older of the two, has been partially freed from the debris and boulders in which it was buried. The other, which shows traces of Buddhist workmanship, and dates from the eleventh century, is decorated with carvings of great beauty. The fort and temples of Kangra town received irreparable damage in the earthquake of 1905.

Population

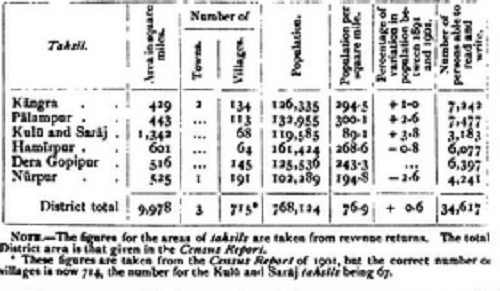

The population of the District at the last four enumerations was : (1868) 743.882, (1881) 730,845, ( 18 91) 763,030. And (1901)768,124, dwelling in 3 towns and 715 villages. It is divided into the seven tahftls of Kangra, Nurpur, HamIr- pur, Dera Gopipur, Palampur, Kulu, and Saraj ; of which the first five are in Kangra proper, the two last forming the Kulfl subdivision. The head-quarters of these are at the places from which each is named, except in the case of Kulu and Saraj, whose head-quarters are at Sultanpur and Banjar respectively. The towns are the munici- palities of Dharmsala, the head-quarters of the District, Kangra, and Nurpur.

The following table shows the chief statistics of population in 1901

In Kingra proper Hindus number 608,252, or 94 per cent of the

total; Muhammadans, 38,685, or 6 per cent; and Sikhs, 1,199.

Owing to the vast tracts of uncultivable hill-side, the density of the

population is only 77 persons per square mile, varying from 300 in

the Palampur tah&l to 65.4 in Kulu ; but if the cultivated area alone

be considered, the density is 834, almost the highest in the Province.

The people speak a great variety of dialects of the group of languages

classed together as PahSrf, or the language of the hills.

The distinguishing feature in the population is the enormous pre- ponderance of the Hindu over the Muhammadan element, the latter being represented only by isolated colonies of immigrants, while the mass of the people have preserved their ancient faith in a manner wholly unknown in the plains. This circumstance lends a peculiar interest to the study of the Hindu tribes — their castes, divisions, and customs.

The Brahmans (109,000) number nearly one-seventh of the total population. Almost without exception, they profess themselves to belong to the great Saraswat family, but recognize an infinity of internal subdivisions. The first distinction to be drawn is that between Br&h- mans who follow, and Brfthmans who abstain from, agriculture. Those who have restricted themselves to the legitimate pursuits of the caste are considered to be pure Brahmans ; while the others are no longer held in the same reverence by the people at large.

The Rajputs number even more than the Brahmans, 154,000 people returning this honourable name. The Katoch Rajas boast the bluest blood in India, and their prejudices and caste restrictions are those of a thousand years ago. The Katoch clan is a small one, numbering only 4,000. The Rathis (51,000) constitute the higher of the two great agricultural classes of the valley, and are found chiefly in the Nurpur and Hamlrpur tahsUs. The other is the Ghirths (120,000), who are Sudras by status. In all level and irrigated tracts, wherever the soil is fertile and produce exuberant, the Ghirths abound; while in the poorer uplands, where the crops are scanty and the soil demands severe labour to compensate the husbandman, the Rathis predominate. It is as rare to find a Rathi in the valleys as to meet a Ghirth in the more secluded hills. Each class holds possession of its peculiar domain, and the different habits and associations created by the different localities have impressed upon each caste a peculiar physio- gnomy and character. The Rathis generally are a robust and handsome race; their features are regular and well-defined, their colour usually fair, and their limbs athletic, as if exercised and invigorated by the stubborn soil upon which their lot is thrown.

On the other hand, the Ghirth is dark and coarse-featured, his body is stunted and sickly, and goitre is fearfully prevalent among his race. The Rathis are atten- tive and careful agriculturists ; their women take little or no part in the labours of the field. The Ghirths predominate in the valleys of Palam, Kangra, and Rihlu. They are found again in the Hal Dun or Harlpur valley, and are scattered elsewhere in every part of the Dis- trict, generally possessing the richest lands and the most open spots in the hills. They are a most hard-working race. »

Among the religious orders in the hills, the most remarkable are the Gosains (1,000), who are found principally in the neighbourhood of Nadaun and Jawala Mukhi, but are also scattered in small numbers throughout the District. Many of them are capitalists and traders in the hills, and they are an enterprising and sagacious tribe. By the rules of their caste retail trade is interdicted, and their dealings are exclusively wholesale. Thus they possess almost a monopoly of the trade in opium, which they buy up in Kulu and carry down to the plains of the Punjab. They speculate also in charas> shawl-wool, and cloth. Their transactions extend as far as Hyderabad in the Deccan, and, indeed, over the whole of India.

Among the hill tribes the most prominent are the Gaddis (9,000). Some have wandered down into the valleys which skirt the base of the Dhaola Dhar, but the great majority live on the heights above. They are found from an elevation of 3,500 or 4,000 feet up to 7,000 feet, above which altitude there is little or no cultivation. They preserve a tradition of descent from refugees from the Punjab plains, stating that their ancestors fled from the open country to escape the horrors of the Musalman invasions, and took refuge in these ranges, which were at that period almost uninhabited. The term Gaddi is a generic name, under which are included Brahmans and Khattris, with a few Rajputs, Rathis, and Thakurs. The majority, however, are Khattris. Besides the Gosains, the commercial castes are the Khattris (7,000) and Suds (6,000). Of the menial castes, the Chamars (leather-workers) are the most numerous (57,000). About 77 per cent, of the population are returned as agricultural.

The Church Missionary Society has a station at Kangra town, founded in 1854, with a branch establishment at Dharmsala; and there is also a station of the Moravian Mission at Kyelang in Lahul, founded in 1857, and one of the American United Presbyterian Mission in Saraj. The District in 1901 contained 203 native Christians.

Agriculture

In the Kangra tahsil the subsoil rests on beds of large boulders which have been washed down from the main ranges, and the upper stratum, consisting of disintegrated granite mixed. , with detritus from later formations, is exceedingly fertile. In the neighbourhood of the secondary ranges the soil, though of excellent quality, is less rich, being composed of stiff marls mixed with sand, which form a light fertile mould, easily broken up and free from stones. A third variety of soil is found wherever the Tertiary formation appears : it is a cold reddish clay of small fertility, containing a quality of loose water-worn pebbles ; there are few trees in this soil, and its products are limited to gram and the poorer kinds of pulse, while in Jhe first two descriptions the hill-sides are well forested and every kind of crop can be grown.

The cultivated area is divided into

fields generally unenclosed, but in some parts surrounded by hedges or

stone walls. In the Kangra valley, where rice cultivation prevails, the

fields descend in successive terraces levelled and embanked, and where

the slope of the land is rapid they are often no bigger than a billiard

table ; in the west of the Dera and Nurpur tahsls, where the country is

less broken, the fields are larger in size, and the broad sipping fields,

red soil, and thick green hedges are charmingly suggestive of a Devon-

shire landscape. In many parts, and notably in the Kangra valley,

wide areas bear a double harvest.

In Kulu proper the elevation is the chief factor in determining the nature of the crops sown, few villages lying as low as 3,000 feet and some as high as 9,000. In both Kangra and Kulu proper the sowing time varies with the elevation, the spring crop being sown from September to December and the autumn crop from April to July. The whole of Lahul and Spiti is covered with snow from December to the end of April, and sowings begin as soon as the land is clear. For the District as a whole the autumn crop is the more important, occupying 53 per cent, of the area cropped in 1903-4.

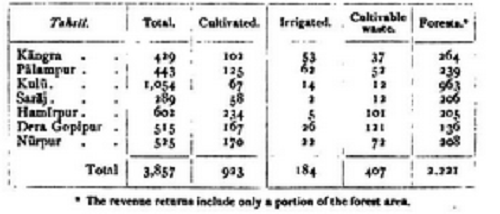

The land is held, not as in the plains by more or less organized village communities, but by individual holders whose rights originated in a grant by a Raja of a right of tenancy in the royal domains. In Kulu only forest and cultivable and cultivated lands have been measured, amounting to 1,342 square miles.

The area for which details are available from the revenue records

of 1903-4 is 3,857 square miles, as shown below: —

Wheat is the chief crop of the spring harvest, covering 342 square miles ; barley covered 97 square miles, and gram only 42. Maize and rice are the mainstay of the autumn harvest, covering 223 and 164 square miles respectively. Pulses covered 100 square miles. Of the millets, mandal, Italian millet, and china are the most important There were 6,039 acres under cotton. The tea industry is an impor- tant one in Kangra, 15 square miles being under tea. There are 34 gardens owned by Europeans, and the total output is estimated at over a million pounds of tea annually l . Potatoes, introduced shortly after annexation, are now largely cultivated in the higher hills ; and the fields round the Gaddi peasants' houses, which formerly produced maize, wheat, or barley hardly sufficient to feed the families which owned them, now yield a very lucrative harvest of potatoes. In Kulti proper poppy is an important crop, covering 2,102 acres. The climate of Kulu is eminently suited for the production of all kinds of European fruits and vegetables, and several European planters do a large trade in pears and apples. In Lahul barley, wheat, peas, and buckwheat are the principal crops, and in Spiti barley.

1 This was written before the earthquake of 1905, which had disastrous effects on the tea industry. The chief improvements in agriculture have been the introduction of tea and the potato. The cultivated area increased by about 5 per cent during the ten years ending 1900, owing to the efforts of indivi- duals who have broken up waste land near their holdings ; but there is no scope for any considerable increase. Loans from Government are not greatly in demand, the total amount advanced under the Agricul- turists' Loans Act during the five years ending 1903-4 being only Rs. 208.

The indigenous breed of cattle is small but strong, and attempts to improve it by the importation of bulls from Hissar have not been satisfactory, the latter being quite unsuited to the climate, and unfitted to mate with the small hill cows. A few bulls of the Dhanni breed have recently been imported from Jhelum District, and it is hoped that they will prove more suitable. The Gujars are the only people who make a trade of selling milk and ghi, and who keep herds of buffaloes ; of these, some have a fixed abode in the District and pasture their cattle in the adjoining waste, while others move with their herds, spending the summer on the high ranges, and the winter in the woody parts of the low hills. Buffalo herds are not allowed to enter the Kulu subdivision. The cattle of Lahul are a cross between the Tibetan yak and the Himalayan breed of cattle.

Sheep and goats form in Kangra

proper the chief support of the pastoral tribe of the Gaddis, who move

with their flocks, wintering in the forests in the low hills, retreating in

the spring before the heat up the sides of the snowy range, and crossing

and getting behind it to avoid the heavy rains in the summer. I^arge

flocks are also kept in the Kulu and Saraj iahslls. There are few

ponies in the District and not many mules ; the ponies of Kangra and

KulQ proper are poor, but those of Lahul and Spiti are known for their

hardiness and sureness of foot. One pony stallion is maintained by

the District board.

Of the total area cultivated in 1903-4, 184 square miles, or nearly 20 per cent., were classed as irrigated. Irrigation is effected entirely by means of channels from the hill streams which lead the water along the hill-sides, often by tortuous channels constructed and maintained with considerable difficulty, and distribute it over the fields. One of these cuts, from the Gaj stream, attains almost the dimensions of a canal, and the channels from the Beas are also important Most of these works were engineered by the people themselves, and supply only the fields of the villages by which they were constructed ; but a few, for the most part constructed by the Rajas, water wider areas, and an organized staff for their maintenance is kept up by the people without any assistance from Government. In Lahul and Spiti culti- vation is impossible without irrigation, and glacier streams are the chief source.

Forests

The forests are of great importance, comprising little short of a quarter of the uncultivated area. Under the Forest department are 87 square miles of ' reserved,' 2,809 of protected, and 296 of unclassed forests, divided into the two Forest divisions of Kangra and Kulfl, each under a Deputy-Conservator. About 4 square miles of unclassed forests are under the Deputy- Commissioner. Several varieties of bamboo cover the lower hills, the bamboo forests occupying an area of 14,000 acres. The produce exported from the Government forests in Kangra proper is mainly chil (Pinus longifolia) and bamboo, while deodar is the chief product of Kulu. In 1903-4 the forest revenue was 28 lakhs.

Minerals

Valuable metal ores are known to exist both in Kangra proper and in Kulu ; but, owing chiefly to the want of means of carriage, of fuel, and of labour, they are practically unworked. Iron was smelted for some years in the Kangra hills, and in 1882 there were eight mines yielding 90 maunds of iron a year; but working ceased entirely in 1897. Ores of lead, copper, and antimony have been found, and in Kulu silver and crystal, while gold in small quantities is sometimes washed from the sands of the Beds and Parbati ; coal, or rather lignite, is also produced, but in insignificant quantities. A lease of the old Shigri mines in Lahul has recently been granted for the purpose of working stibnite and galena. With this exception, the only minerals at present worked are slates and sandstone for building ; the Kangra Valley Slate Company sells 700,000 slates annually, and three other quarries produce together about 83,000, the total value exceeding Rs. 50,000. Several hot mineral springs near Jawala Mukhi are impregnated with iodide of potassium and common salt. Hot springs occur at several places in Kulu, the most important being at Manikarn in the Parbati valley, and at Bashist near the source of the Beas.

Trade and communication

The District possesses no factories except for the manufacture of tea, and there are but few hand industries. The cotton woven in the villages holds its own against the competition of European stuffs, but the industry is seriously handi- capped by the small quantity of cotton grown locally. Nurpur used to be a seat of the manufacture of pashniina shawls, but the industry has long been declining; silver ornaments and tinsel printed cloths are made at Kangra. Baskets are made in the villages of Kangra proper and Kulu, and blankets in Kulu, Lahul, and Spiti.

The principal exports to the plains consist of rice, tea, potatoes, spices, opium, blankets, pashmlna, wool, gha , honey, and beeswax, in return for which are imported wheat, maize, gram and other pulses, cotton, tobacco, kerosene oil, and piece-goods. The chief centres of the Kangra trade in the plains are Hoshiarpur, Jullundur, Amritsar, and Pathankot. There is a considerable foreign trade with Ladakh and Yarkand through Sultanpur in Kulu, the exports being cotton piece-goods, indigo, skins, opium, metals, manufactured silk, sugar, and tea, and the imports ponies, borax, charas, raw silk, and wool. The principal centres of internal trade are Kangra, Palampur, Sujanpur Tira, Jawala Mukhi, and Nurpur.

No railway traverses the District, though one from Pathankot to Palampur was contemplated. The principal roads are the Kangra valley cart-road, which connects Palampur and Pathankot, with a branch to Dharmsala, and the road from Dharmsala, via Kangra, to Hoshiarpur and Jullundur. The former is partly metalled and a mail tonga runs daily. A road runs from Palampur to Sultanpur in Kulu over the Dulchi pass (7,000 feet), which is open summer and winter, going on to Simla. Another road runs through Kulu, and, crossing the Rohtang pass (13,000 feet) into Lahul, forms the main route to Leh and Yarkand. Ladakh is reached from Lahul over the Bara Lacha (16,250 feet). The usual route to Spiti is through Lahul and over the Kan- zam pass. The total length of metalled roads is 56 miles, and of un- metalled roads 1,073 miles. Of these, all the metalled and 353 miles of the un metalled roads are under the Public Works department, and the rest under the District board.

Famine is unknown, the abundance of the rainfall always assuring a sufficient harvest for the wants of the people, and the District was classed by the Irrigation Commission of 1903 as secure. The area of crops matured in the famine year 1899-1900 amounted to 69 per cent, of the normal.

Administration

The District is in charge of a Deputy-Commissioner, aided by three Assistant or Extra-Assistant Commissioners, of whom one is in charge of the Kulu subdivision and one in charge of the District treasury. Kangra proper is divided into the five tahsils of Kangra, Nurpur, Hamirpur, Dera Gopipur, and Palampur, each under a tahsildar and a naib-tahsildar ; the Kulu Subdivision, consisting of the Kulu tahsll under a tahsildar and a naib- tahsildar^ the Saraj tahsll under a naib-tahsllddr ; and the mountainous tracts of Lahul and Spiti, which are administered by local officials termed respectively the thakur and nono. The thakur of Lahul has the powers of a second-class magistrate and can decide small civil suits ; the nono of Spiti deals with all classes of criminal cases, but can punish only with fine. The criminal administration of Spiti is conducted under the Spiti Regulation I of 1873. Two officers of the Forest department are stationed in the District.

The Deputy-Commissioner as District Magistrate is responsible for the criminal justice of the District, under the supervision of the Sessions Judge of the Hoshiarpur Sessions Division. The subdivisional officer of Kulu hears appeals from the tahsllddr of Kulu, the naib-tahslldar of Saraj, the thdkur of Lahul, and the notw of Spiti. Civil judicial work in Kangra proper is under a District Judge, under the Divisional Judge of the Hoshiarpur Civil Division. In Kulu the subdivisional officer generally exercises the powers of a District Judge, and the Deputy- Commissioner of Kangra, if a senior official, is appointed Divisional Judge of Kulu. The only Munsif sits at Kangra, while there are seven honorary magistrates, including the Rajas of Lambagraon, Nadaun, and Kutlehr in Kangra proper. The District is remarkably free from serious crime. Civil suits are chiefly brought to settle questions of inheritance involving the rights inter se of widows, daughters, and distant agnatic relatives.

The revenue history and conditions differ radically from those of the Punjab proper. The hill states, now combined in Kangra District, were merely a number of independent manors. Each Raja enjoyed full proprietary rights, and was a landlord in the ordinary sense of the word, leasing his land at will to individual tenants on separate pattas or leases. This fact explains the two prominent characteristics of the revenue system, its variety and its continuity. Just as, on the one hand, the intimate local knowledge of the Raja and his agent enabled them to impose a rent fixed or fluctuating, in cash or kind, according to the resources and the needs of each estate, so, on the other hand, the conquerors, Mughal and Sikh, imposed their tribute on the several Rajas, leaving them to devise the source and the method of collection. The Mughals, it is true, reserved certain areas as imperial demesnes, and here they introduced chaudhris who were responsible both for the collection of the revenue and for the continued cultivation of the soil. They made no change, however, either in assessments or in methods of collection.

The Rajas depended on their' land-agents (called variously

kardar y hakim, amin, or palsara), and these in turn had under them

the kotwals, who were responsible for eight or ten villages apiece. The

village accountant, or kdyat y the keeper of the granary (kotiala),with

constables, messengers, and forest watchers, made up the revenue

staff. Every form of assessment was to be found, from the division

of the actual produce on the threshing-floor to permanent cash assess-

ments.

Ranjlt Singh was the first to interfere with the Rajas' system. He

appointed a nazim, or governor of the hill territory, who managed not

only the revenue, but the whole expenditure also. Under him were

kdrddrsy who either farmed the revenue of their parganas, or accepted

a nominal salary and made what they could. The ancient system,

however, has survived the misrule of the Sikhs. Every field in the

valley is clearly defined ; and the proportion of its produce payable to

Government is so firmly established that, even under the present cash

assessments, it forms the basis on which the land revenue is distributed

among individual cultivators.

The first act of the British officers was to apply the village system of

the plains to the Kangra valley. The tenants, with their private cul-

tivating rights, became the proprietary body, with joint revenue-paying

responsibilities. The waste, formerly regarded as the property of the

Rajas, became attached to the village communities as joint common

land. The people thus gained the income arising from the common

land, which had previously been claimed by the state.

A summary settlement was made in 1846 by John Lawrence, Com- missioner of the Jullundur Doab, and Lieutenant Lake, Assistant Com- missioner, based entirely on the Sikh rent-roll with a reduction of 10 per cent. The first regular settlement, made in 1849, reduced the demand on ' dry ' land by 1 2 per cent., maintaining the former assess- ment on ‘ wet’ land. A revised settlement, made in 1 866-7 1, had for its object the preparation of correct records-of-rights ; but the assess- ment was not revised until 1889-94, when an increase of 19 per cent, was announced. Rates varied from Rs. 1-5-4 to R. 0-14-7 per acre. The total demand in 1903-4, including cesses, was about 10-7 lakhs. The average size of a proprietary holding is 2 acres. There are a num- ber of large jdgfrs in the District, the chief of which are Lambagraon, Nadaun, and Dado Slba in Kangra proper, and wazlri Rilpi in Kulu.

A system of forced labour known as begat was in vogue in the Kangra hills until recently, and dates back from remote antiquity. All classes who cultivate the soil were bound to give, as a condition of the tenure, a portion of their labour for the exigencies of the state. Under former dynasties the people were regularly drafted and sent to work out their period of servitude wherever the ruler chose. So inveterate had the practice become that even artisans, and other classes unconnected with the soil, were obliged to devote a portion of their time to the public service. Under the British Government the custom was main- tained for the conveyance of travellers' luggage and the supply of grass and wood for their camps, but was practically abolished in Kangra proper in 1884, and in Kulu in 1896.

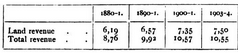

The collections of land revenue alone and of total revenue are shown below, in thousands of rupees : —

The District contains three municipalities, Dharmsala, Kangra, and Nurpur. Outside these, local affairs are managed by a District board, and by the local boards of Kangra, Nurpur, Dera Gopipur, Hamirpur, and Palampur, the areas under which correspond with the tahsils of the same names. The chief source of their income is the local rate, a cess of Rs. 8-5-4 per cent, on the land revenue in Kangra, of Rs. 10-6-8 in Kulu, and of Rs. 7-8-10 in the wazlri of Spiti. The expenditure in 1903-4 was Rs. 1,45,000, public works being the principal item.

The District is divided into 15 police stations, 13 in Kangra proper and 2 in Kulu ; and the police force numbers 412 men, with 901 village watchmen. The Superintendent usually has three inspectors under him. The jail at head-quarters contains accommodation for 150 prisoners. It has, however, been condemned as unsafe, and a new- one is in contemplation.

Kangra stands seventh among the twenty-eight Districts of the Province in respect of the literacy of its population. In 1901 the pro- portion of literate persons was 45 per cent. (84 males and 0-3 females). The number of pupils under instruction was 2,591 in 1880-1, 3,881 in 1890-1, 3,341 in 1900-1, and 3.852 in 1903-4. In the last year the District contained 6 secondary and 57 primary (public) schools for boys and 9 for girls, and 3 advanced and 20 elementary (private) schools, with 266 girls in the public and 38 in the private schools. The principal educational institution is the high school at Palampur, founded in 1868, and maintained by the District board. There are 5 middle schools for boys, of which 2 are Anglo-vernacular ; 3 of these are maintained by the District board and 2 are aided. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 35,000, of which Rs. 7,000 was derived from fees, Rs. 4,000 from Government grants, and Rs. 2,000 from subscriptions and endowments. Municipalities contributed Rs. 4,000, and the balance was paid out of District funds.

Besides the civil hospital at Dharmsala, the District has 8 out- lying dispensaries. In 1904, 739 in-patients and 101,159 out-patients were treated, and 1,769 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 19,000, of which Rs. 14,000 was met from District and Rs. 3,000 from municipal funds.

The number of successful vaccinations in 1903-4 was 40,825, repre- senting the high proportion of 53 per 1,000 of the population. Vaccina- tion is compulsory in Dharmsala.

[H. A. Rose, District Gazetteer of Kangra Proper (190$) ; A. Ander- son, Settlement Report of Kangra Proper (1897); A. H. Diack, Gazetteer of Kulu, Ldhul, and Spiti (1897), The Kulu Dialect of Hindi (1896), and Settlement Report of Kulu Subdivision (1898).]