Kanara, South

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Kanara, South

Physical aspects

The more northerly of the two Districts on the west coast of the Madras Presidency, lying between 12 degree 7' and 13 degree 59' N. and 74 degree 34' and 75 degree 45' E., with an area of 4,021 square miles.

The vernacular name Kannada ('the black country') really refers to the black soil of the Kanarese-speaking country in the Southern Deccan. Though a historical misnomer as applied to the western seaboard, it yet marks its long subjection to the Kanarese princes who held sway over the Western Ghats. The District is bounded on the north by the Bombay Presidency; on the east by Mysore and Coorg; on the south by Coorg and Malabar; and on the west by the Arabian Sea.

The scarp or watershed of

the Western Ghats forms a natural frontier on the

east. Approaching in the extreme north within 6

miles of the sea, the main line of this range soon swerves abruptly

eastward round the Kollur valley. Through this passes a road leading

to the Honnar Magane, a small tract above the Ghats belonging to

South Kanara, but separated from it by Mysore territory. South of

the valley rises the prominent sugar-loaf peak of Kodachadri, 4,411

feet ; and thence, a precipitous cliff-like barrier with an average eleva-

tion of over 2,000 feet, the Ghats run south-east to the Kudremukh,

the highest peak in the District, 6,215 fee* above sea-level. From

this point they sweep east and south round the Uppinangadi taluk

to join the broken ranges of the Coorg and Malabar hills on the

southern boundary of the District. South of the Kudremukh their

character entirely changes.

To the north few passes or prominent

heights break the clearly defined watershed. On the south, deep

valleys pierce the main line, flanked by massive heights such as Bal-

lalrayandurga (4,940 feet) and Subrahmanya hill (5,626), while a pro-

fusion of forest-clad spurs and parallel ranges makes the scenery as

varied and picturesque as any in the Presidency. West of the Ghats

a broken laterite plateau slopes gradually towards the sea. The general

aspect of the District has been well described as a flatness uniform

but infinitely diversified. Much of the level surface is bare and tree-

less, and strewn with denuded granite boulders; but numerous miniature

hill ranges, well wooded save where stripped for firewood near the

coast, and bold isolated crags rising abruptly from the plain, prevent

monotony.

Local tradition states that South Kanara was part of the realm wrested by the mythic Parasu Rama from the sea, and modern geology seems to confirm the view that it is an ancient sea-bed. Water is at any rate the element to which the District owes its dis- tinctive characteristics. The monsoons have furrowed innumerable valleys in the laterite downs, and fertilized them with rich soil washed down by the streams. Valley opens upon valley in picturesque and diversified similarity, all converging at last into the main valleys through which the larger rivers of the District run. Along the back- water which these rivers form at the coast are found large level stretches of fertile rice and garden land. From the sea, indeed, the coast-line presents an endless stretch of coco-nut palms, broken only by some river mouth or fort-crowned promontory where the main level of the plateau runs sheer into the sea.

The rivers of the District, though numerous, are of no great length. Raging torrents in the monsoon, owing to the enormous volume of water they have to" carry off, in the hot season they shrink to shal- low channels in the centres of their beds. Rapid in their early course, they expand at the coast into shallow tidal lagoons. In the extreme south a number of rivers rising in the Malabar and Coorg hills form a succession of backwaters giving water communication with Malabar. At Kasaragod the Chandragiri (Payaswani) flows into the sea past an old fort of the same name. The Netravati, with its affluent the KumSradhari, and the Gurpilr river, which have a common back- water and outlet at Mangalore, drain the greater part of the Mangalore and Uppinangadi taluks.

The SwamanadI and the Sft&nadl drain most of the Udipi taluk and have a common outlet at the port of Hang&rkatta. A picturesque and important backwater studded with fertile islands is formed to the north of Coondapoor town by a number of rivers draining much of the Coondapoor taluk.

The geology of South Kanara has not yet been worked out. It is probable that in the main it consists of Archaean gneisses of the older sub-groups, possibly with representatives of the upper thinner-bedded more varied schists (Mercfira schists) and plutonic igneous rocks where the District touches Mysore and Coorg. Laterite and ordinary coastal alluvium are common in the low-lying parts.

As might be expected from the heavy rainfall (145 inches), the flora of the District is exceedingly varied. The forests are both evergreen and deciduous, and the more important timber trees are mentioned under Forests below. Of fruit trees, the coco and areca palms and the jack and mango are the most important. There are, however, few good grafted mango-trees, except in Mangalore town. The palmyra palm is found everywhere, and the cashew-tree is very common, especially near the coast. The bamboo grows luxuriantly. Consider- able stretches of sandy soil along the coast have been planted with the casuarina. The betel vine, yams of various kinds, and plantains are raised in gardens, and turmeric and chillies as occasional crops. Flowers of numberless kinds grow in profusion, and in the monsoon every hollow and wall sprouts with ferns and creepers.

The fauna is varied. Leopards are found wherever there is cover, and annually destroy large numbers of cattle. The tiger is less common. On the Ghats bison (gaur) and sambar attract sportsmen, and the black bear is also found, while elephants are fairly numerous in the extensive forests of the Uppinangadi taluk. Deer and monkeys do considerable damage to cultivation near the Ghats. The jackal is ubiquitous.

The handsome Malabar squirrel (Sciurus indicus) is common in the forests, and flying foxes have established several flourishing colonies. Among rarer animals are the flying squirrel, lemur, porcupine, and pangolin. Many species of snakes exist, and the python and the hamadryad (Ophiophagus elaps) grow to an immense size. Crocodiles and otters are found in the larger streams. There is good fishing in the rivers, mahseer being numerous; but dynamiting, poisoning, and netting by the natives have done much to spoil it.

The climate is characterized by excessive humidity, and is relaxing and debilitating to Europeans and people of sedentary habits. The annual temperature at Mangalore averages 8i°. The heat is greatest in the inland parts of the District during the months of March, April, and May. Malarial fever is rife during the hot season and the breaks in the monsoon wherever there is thick jungle. From November to March a chilly land wind blows at night which, though it keeps the temperature low, is unhealthy and reputed especially dangerous to horses.

The annual rainfall averages 145 inches. It is smallest on the coast line, ranging from 127 inches at Hosdrug in the south to 141 inches at Ceondapoor in the north. The farther inland one goes the greater is the amount, Karkala close to the Ghats having an average of 189 inches. In 1897 the enormous fall of 239 inches was recorded at this station. Of the total amount, more than 80 per cent, is received during the four months from June to September in the south-west monsoon. The rains may be said never to fail, and the District has only once known famine. Floods, however, are rare, as the rivers have usually cut themselves very deep channels.

History

Little is known of the early history of South Kanara. Inscriptions show that it was included in the kingdom of the Pallavas of Kanchi, the modern Conjeeveram in Chingleput District, whose earliest capital appears to have been Vatapi or Badami, in the Bijapur District of Bombay. Its next rulers seem to have been the early Kadamba kings of Banavasi, the Banaousir of the Greek geographer Ptolemy (second century a.d.), in North Kanara District. About the sixth century they were overthrown by the early Chalukyas, who had established themselves at Badami, the old Pallava capital.

In the middle of the eighth century these were expelled by

the later Kadamba king Mayuravarma, who is said to have introduced

Brahmans for the first time into the District. His successors seem to

have ruled the country as feudatories of the RSshtrakutas of Malkhed

in the present Nizam's Dominions, and of the Western Chalukyas of

Kalyani in the same State. About the twelfth century the District was

overrun by the Hoysala Ballalas of Dorasamudra, the modern Halebld

in Mysore. But there were frequent contests between them and the

Yadavas of Deogiri, the modern Daulatabad in the Nizam's Domi-

nions, until in the fourteenth century they were both overthrown by the

Delhi Muhammadans, practically securing the independence of the

local chiefs.

In the first half of the fourteenth century the District passed under the Hindu kings of Vijayanagar. About this time Ibn Batuta, the Muhammadan traveller, passed through it, and has left an interesting, though somewhat exaggerated, description of what he saw. During the next century the Portuguese made their first settlements on the west coast, and Vasco da Gama himself landed in 1498 on one of the islands off Udipi. After the battle of Talikota in 1565, in which the last Vijayanagar king was defeated by the united Muham- madans of the Deccan, the local Jain chiefs achieved independence. But in the beginning of the next century almost all of them were subdued by the Lingayat ruler, Venkatappa Naik, of Ikkeri, now a vil- lage in the Shimoga District of Mysore.

During the next century and

a half the Ikkeri chieftains, who had meanwhile removed their capital

to Bednur, the present Nagar in Mysore, continued masters of the

country, though most of the old Jain and Brahman chiefs seem to have

retained local independence.

British connexion with the District begins about 1737, when the factors at Tellicherry, taking advantage of a hostile move by the Bednur Raja, obtained commercial advantages, including a monopoly of all pepper and cardamoms in certain tracts. Haidar All, the Muhammadan usurper of the Mysore throne, after his conquest of Bednur in 1763 took Mangalore and made it the base of his naval operations. The place was captured by the English in 1768, but, on Haidar's approach a few months later, was evacuated. On the out- break of war with Haidar again in 1780, General Mathews, Com- mander-in-Chief of Bombay, landed opposite Coondapoor and took it. On his subsequent march north to Bednur, he also took Hosangadi and the Haidargarh fort.

Bednur itself next fell, but the arrival of a large relieving force under Tipu, Haidar's son, forced Mathews to capitulate. Tipu then besieged Mangalore, which surrendered after a protracted struggle. During this war, Tipu, suspecting that the native Christians of the District were secretly aiding the English, deported large numbers of them to Mysore and forcibly converted them to Isl£m. During the final war with Tipu, which ended in his death at the fall of Seringapatam in 1 799, the District suffered severely from the depredations of the Coorgs. By the Partition Treaty of the same year it fell to the British. To the country thus acquired. was added in 1834, on the annexation of Coorg, the portion of that province which had been ceded to the Coorg Raja in 1799. In 1862 the country north of the Coondapoor taluk was transferred to the Bombay Presidency, leaving the District as it now stands to the administration of Madras.

The chief objects of archaeological interest in South Kanara are its Jain remains, which are among the most remarkable in the Presidency. The most noteworthy are found at Karkala, Mudbidri, and Yenur, in a part of the District long ruled by Jain chiefs, of whom the most important were the Bhairarasa Wodeyars of Karkala. Under this family, which migrated from above the Ghats, building in stone is supposed to have been introduced into this part of the west coast Fergusson states that the architecture of the Jain temples has no resemblance to the Dravidian or other South Indian styles, but finds its nearest affinity in Nepal and Tibet. There is no doubt that it is largely a reproduction of the architectural forms in wood used in the country from early times. The remains are of three kinds. The first are the bettas y or walled enclosures containing colossal statues. There is one of these statues at Karkala and another at Yenur.

The former is the larger, being 41 feet 5 inches high, and is also the more striking, as it stands on the top of a rocky hill overlooking a picturesque lake. They both have the traditional forms and lineaments of Buddha, but are named after Gomata Raya, a forgotten and perhaps mythical Jain king. They are monolithic ; and the method of their construction, whether they were hewn out of some boulder which stood on their sites, or whether they were sculptured elsewhere and removed to their present positions, is a mystery. A still larger statue, also said to be of Gomata Raya, at Sravana Belgola in Mysore is the only other example known. An inscription on the Karkala statue states that it was erected in a.d. 1 43 1. The second class of Jain remains are the bastfs or temples. These are found all over the District, the most famous group being at Mudbidri, where there are eighteen of them. With plain but digni- fied exteriors, clearly showing their adaptation from styles suited to work in wood, and greatly resembling the architecture common in Nepal in the reverse slope of the eaves above the veranda, nothing can exceed the richness and variety with which the interior is carved.

The

largest basfi at'Madbidri is three-storeyed, resembling somewhat the

pagodas of the Farther East, and contains about 1,000 pillars, those of

the interior being all carved in the most varied and exuberant manner.

The last variety of Jain antiquities are the stambhas or pillars.

Though not peculiar to Jain architecture, the most graceful examples

are found in connexion with the temples of that faith. The finest is at

Haleangadi near Karkala. It is 50 feet from base to capital, the shaft

being monolithic and 33 feet in length, and the whole gracefully pro-

portioned and beautifully adorned. Barkur, once the Jain capital of

the region destroyed by Lingayat fanatics in the seventeenth century,

probably excelled the rest of the District in the number and beauty of

its buildings ; but these are now a mere heap of ruins.

Serpent stones in groves and on platforms round the sacred fig- trees are numerous, bearing witness to the tree and serpent worship imposed by the influence of Jainism and Vaishnavism on the primitive demon and ancestor worship of the country. The Hindu temples are as a rule mean and unpretentious buildings, though many of them, such as that to Krishna at Udipi and the shrines at Subrahmanya, Kollur, Sankaranarayana, and Koteshwar, are of great antiquity and sanctity. Forts are numerous, especially along the sea-coast, but of little impor- tance archaeologically. That at Bekal is the largest, and was formerly a stronghold of the Bednur kings.

Population

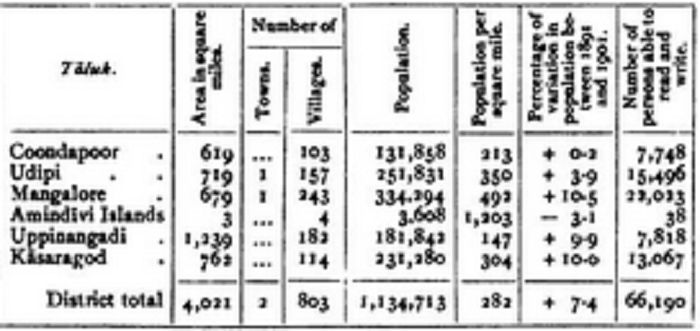

South Kanara is divided into the five taluks of Coondapoor, Kasa- ragod, Mangalore, Udipi, and Uppinangadi, and includes also the Amindlvi Islands in the Indian Ocean. The head- op ' quarters of the taluks (except of Uppinangadi, which is at Puttur) are at the places from which they are respectively named. The headman of the Amindlvis lives on the Amini island. Statistics of these areas, according to the Census of 1901, are shown in the table on the next page.

Much of South Kanara is hill and forest ; and the density of the population is accordingly little above the average for the Presidency as a whole, fertile and free from famine though the District is. In the Uppinangadi taluk y which lies close under the Ghats, there are only 147 persons to the square mile. This is, however, on the main road to Mysore and Coorg, and the opportunities for trade thus afforded have caused the population here to increase faster than in the District as a whole.

The population of South Kanara in 187 1 was 918,362; in 1881,

959,514; in 1891, 1,056,081 ; and in 1901, 1,134,713. It will be seen

that the growth, though steady, is not remarkable. In the decade

ending 1901 the rate of increase was about equal to the average for the

Presidency, and during the last thirty years it has amounted to 24 per

cent There is considerable temporary emigration of labourers every year

to the coffee estates of Coorg and Mysore, the total loss to the District

in 1 90 1 on the movement between it and these two areas being 14,000

and 40,000 persons respectively. On the other hand, South Kanara

obtains very few immigrants from elsewhere.

In 190 1 less than 2 persons in every 100 found within it had been born outside. As in the case of Malabar, this is largely due to its geographical isolation, and to the fact that the ways and customs of its people and its agricultural tenures differ much from those of neighbouring areas. The people are fonder of living in their own separate homesteads than in streets, and the District consequently has a smaller urban population than any other except Kuraool and the Nilgiris, and includes only two towns. These are the municipality of Mangalore (population, 44,108), the District head-quarters, and the town of Udipi (8,041). Both are growing places. There are few villages of the kind usual on the east coast, the people living in scattered habitations.

Of the total population in 1901 Hindus numbered 914,163, or 81

per cent; Musalmans, 126,853, or 11 per cent.; Christians, 84,103,

or 7 per cent. ; and Jains, 9,582, or 1 per cent. Musalmans are propor-

tionately more numerous than in any Districts except Malabar, Madras

City, and Kuraool ; and most of them are Mappillas, who are described

in the article on Malabar. Excluding the exceptional cases of Madras

City and the Nilgiris, Christians form a higher percentage of the people

than in any District except Tinnevelly. They have increased at the

rate of 45 per cent, during the last twenty years. Jains are more

numerous than in any other District of Madras.

South Kanara is a polyglot District Tulu, Malayalam, Kanarese, and Konkani are all largely spoken, being the vernaculars respectively of 44, 19, 19, and 13 per cent of the population. Tulu is the language of the centre of the District, and is used more than any other tongue in the Mangalore, Udipi, and Uppinangadi taluks ; but in Mangalore a fifth of the people speak Konkani, a dialect of MarathI, and in Udipi nearly a fourth speak Kanarese. In the Amindlvi Islands and in Kasaragod, which latter adjoins Malabar, Malay&lam is the prevailing vernacular. Most of those who are literate are literate in Kanarese. It is the official language of the District, and its rival, Tulu, has no written character, though it has occasionally been printed in Kanarese type.

The District contains proportionately more Bralimans than any other in Madras, the caste numbering 110,000, or 12 per cent, of the Hindu population. The Hindus are made up of many elements, and the castes are in need of more careful study than they have yet received. They include 16,000 Telugus (9,000 of whom are Devanga or Sale weavers) ; 82,000 members of Malay&lam castes (most of whom are found in the Kasaragod taluk) ; 140,000 people of MarathI or Konkani- speaking communities; and 672,000 who talk Kanarese or Tulu.

The three largest castes in the District are the Billavas (143,000), the Bants (118,000), and the Holeyas (118,000). The first two of these hardly occur elsewhere. They are respectively the toddy-drawers and the landholders of the community. The Holeyas are nearly all agricultural labourers by occupation.

Except the three Agencies in the north of the Presidency and South Arcot, South Kanara is more exclusively agricultural than any other District As many as three-fourths of its people live by the land. Toddy-drawers are also proportionately more numerous than usual, though it must be remembered that many toddy-drawers by caste are agriculturists or field-labourers by occupation, while weavers and leather-workers form a smaller percentage of the people than is normally the case.

Out of the 84,103 Christians in the District in 1901, 83,779 were

natives, more than 76,000 being Roman Catholics. Tradition avers

that St Thomas the Apostle visited the west coast in the first century.

The present Roman Catholic community dates from the conquest

of Mangalore by the Portuguese in 1526. Refugees from the Goanese

territory driven out by Maratha incursions, and settlers encouraged

by the Bednur kings, swelled the results of local conversion, so that

by Tipu's time the native Christian community was estimated at

80,000 souls. But after the siege of Mangalore in 1784 Tipu deported

great numbers of them, estimated at from 30,000 to 60,000, to Seringa-

patam, seized their property, and destroyed their churches. Many of

them perished on the road and others were forcibly converted.

On the fall of Seringapatam the survivors returned, and the community was soon again in a prosperous condition. The jurisdiction of Goa continued until 1837, when part of the community placed themselves under the Carmelite Vicar Apostolic of Verapoli in Travancore. After further vicissitudes the Jesuits took the place of the Carmelites in 1878. Mangalore is now the seat of a Roman Catholic bishopric.

The only Protestant mission is the German Evangelical Mission of Basel, established at Mangalore in 1834. Its converts now number 5,913, mainly drawn from the poorest classes of the people, who find employment in the various industrial enterprises of the mission.

Agriculture

The agricultural methods of South Kanara are conditioned by its climate and geological peculiarities. As already mentioned, the District is a laterite plateau on a granite bed, bounded by the . Ghats, and worn and furrowed into countless valleys by the action of the monsoons. Much of the level plateau above the valleys produces nothing but thatching-grass or stunted scrub ; but the numerous hollows are the scene of rich and varied cultivation, and the slopes above the fields are well wooded save where denuded to supply the fuel markets of Mangalore and other large towns.

The soil is as a rule a laterite loam, which is especially rich in the lower stretches of the valleys, where the best rice land is found. Large stretches of level ground occur along the coast, where the soil is generally of a sandy character but contains much fertilizing alluvial matter. To the north of the Chandragiri river this land grows excellent rice crops and bears a very heavy rent. South of that stream the soil is thinner and suited only to the commoner kinds of rice ; but tobacco and vegetables are grown in considerable quantities, especially by the Mappillas.

Every valley has one or more water channels running through its centre or down either side. The best rice-fields lie as a rule on a level with these channels, which feed them during the whole of the first-crop season by small openings in their embankments that can be shut or opened as needed. After the first crop of rice has been harvested, dams are thrown across these channels at intervals ; and by this means the level of the water is maintained, and a second, and even a third, crop of rice can be grown by direct flow from the channel, water being let into the plots as required. Very often a permanent dam is main- tained above the cultivation, to divert part of the water down the side channels.

In the land immediately above these side channels a second

crop of rice is grown by bailing either with picottahs, or, when the level

admits, with hand-scoops (kaidambt) suspended from a cross-bar, or with

a basket swung with ropes by two men. These lands are locally termed

majaL Still higher up the slopes of the valley are other rice-fields,

known as bettu, cut laboriously in terraces out of the hill-sides. These

give only one crop of rice and, except. where fed by some small jungle

stream, are entirely dependent on the rainfall; consequently their

cultivation is somewhat precarious. The areca gardens are mostly

situated in the sheltered nooks of the valleys in the more hilly parts of

the District and in the recesses of the lower spurs and offshoots of the

Ghats, where the two essentials of shade and a perennial water-supply

occur in combination.

The finest coco-nut gardens are found in the

sandy level stretches adjoining the coast, especially along the fringes

of the numerous backwaters.

A considerable quantity of black gram, horse-gram, and green gram

is grown on the level land near the coast as a second crop, and on

majal lands elsewhere if sufficient moisture is available. Sugar-cane

is grown here and there beside the backwaters. Pepper has never

recovered from the measures taken by Tipu to suppress its cultivation.

In the south of the Kasaragod taluk, kumrt, or shifting cultivation,

is still carried on in the jungles.

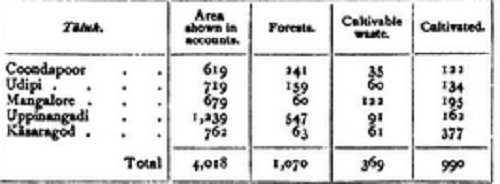

The District is essentially ryotwari, such indms as exist being merely assignments of land revenue. Statistics of the various taluks for 1903-4 are appended, areas being in square miles : —

More than a fourth of the District consists of forest, nearly one-half

is hilly and rocky land not available for cultivation, and the area

actually cropped is less than a fifth of the total. Rice is by for the

most important staple, the area under it (counting twice over that

cropped twice) being 760 square miles. The garden area, 82 square

miles, consists almost entirely of coco-nut and areca-nut plantations.

These three crops practically monopolize the cultivation.

For agricultural purposes the ryots divide the year into three seasons, to correspond with the times of the three rice crops. These are Kartika or Yenel (May-October), Suggi (October-January), and Kolake (January-April). It is doubtful if any District in the Presi- dency shows such a round of orderly and careful cultivation, and the increased out-turn from any theoretical improvements that might be made would probably be more than counterbalanced by the enhanced cost of cultivation. The choice and rotation of crops, the properties of various soils, the selection of seed and of seed-beds, the number of ploughings, the amount of manure, the distribution of water, the regulation of all these, and the countless other details of high farming, if based on no book knowledge, have been minutely adapted by centuries of experience and tradition to every variety of holding.

In the jungles which almost everywhere adjoin the cultivation the ryot finds an unfailing supply of manure for his fields, of timber for his agricultural implements, which he fashions at little expense to himself, and of fuel for domestic use. Consequently he has availed himself but little of the Land Improvements Loans Act. Under the name of kutnaki, holders of kadint wargs, or holdings formed before 1866, enjoy these privileges to the exclusion of others within 100 yards of the cultivation. No figures are available to show the extension of tillage.

The absence of a survey, the connivence of the village and

subordinate revenue officials, and the nature of the country have made

encroachments particularly easy; and land has been formally applied

for only where the prior right to it has been disputed, or to serve as

a nucleus for future encroachment. Cultivation has increased steadily

everywhere except immediately under the Ghfits, where the miseries

and depopulation caused by the disturbances of the eighteenth century

threw out of cultivation large tracts which have never recovered, owing

to the prevalence of malaria and the demand for labour elsewhere.

The chief drawback to agriculture in South Kanara is the want of a good indigenous breed of cattle. All the best draught and plough cattle have to be imported from Mysore,~and even where well tended they are apt to deteriorate. The ordinary village cattle, owing to exposure to the heavy rains, indiscriminate breeding, bad housing, and a regime of six months' plenty and six months' want, are miserably undersized and weakly. The climate is equally unfavourable to sheep and horses, the number of which is small and kept up only by importa- tion. A fair is held annually at Subrahmanya, to which about 50,000 head of cattle are brought from Mysore to meet local requirements.

The heavy rainfall and the rapid nature of the rivers do not admit of large irrigation reservoirs or permanent dams being formed, and as a result there are no Government irrigation works in the District. But the ryots have themselves most skilfully utilized the springs and streams by countless channels, feeders, and temporary dams. Along the coast, cultivation is largely assisted by shallow ponds scooped at little expense out of the sandy soil, and farther inland reservoirs of a more substantial nature are sometimes constructed at the valley heads. Many areca gardens are so supplied.

Forest

South Kanara is essentially a forest District. With the exception of the bare laterite plateaux and downs of the Kasaragod and Manga- lore taluks, and the spots where the hills near the coast have been stripped of their growth for timber, fuel, and manure, the country is everywhere richly wooded.

The whole

line of the Ghats with their spurs and offshoots presents an almost

unbroken stretch of virgin forest, which finds its richest and most

luxuriant development in the recesses of the Uppinangadi taluk, where

the most important and largest Reserves are found. The total forest

area in the District is 662 square miles, and 408 square miles of

'reserved' land are also controlled by the Forest department In

the early years of British administration the claims of Government to

the forests and their prospective importance were alike overlooked;

but the rights of the Crown began to be asserted from the year 1839

onwards, and during the last thirty years Reserves have been selected

and a system of conservation introduced.

The destructive system of shifting cultivation, locally known as kumri, has been prohibited since i860, except in a few small tracts where it is strictly regulated. Such regulation is a matter of the greatest importance to a District with an annual rainfall averaging over 140 inches, the seasonable distribution of which depends largely on the proper protection of its catchment area.

The most valuable timber trees are teak, poonspar (Calophyllum elatutn), black-wood (Dal) ventek (Lagerstroemta microcarpa) kiralbhog (Hopea parviflora) banapu (Terminalia tomentosa) and marva (T.pani- culata). But development must still be said to be in its infancy. In fact, the chief revenue is at present derived from items of minor produce, such as catechu, grazing fees, &c. The main obstacle is the want of good communications ; but once this is overcome, whether by a system of light railways or otherwise, the South Kanara forests should be of the greatest value.

A fine clay excellently adapted for pottery is found in several

localities, especially along the banks of the Netravati, which supplies

material for the Mangalore tile-works mentioned below. Gold and

garnets are known to occur in one or two places, but the mineral

resources of the District are as yet practically unexplored. The

ordinary laterite rock, which is easily cut and hardens on exposure,

forms the common building material.

Trade and communication

The only large manufactures in South Kanara are the results of European enterprise. Tile-making was introduced by the Basel Mission, and this body has now two factories at Mangalore and another at Malpe near Udipi. At Mangalore one other European firm and nine native merchants are engaged in the industry, and elsewhere in the District are two more native factories. The industry employs altogether about 1,000 hands.

The Basel Mission has also a large

weaving establishment at Mangalore, and some of its employes have

started small concerns elsewhere; but otherwise the weaving of the

District is of the ordinary kind. The same may be said with reference

to the work of the goldsmiths, blacksmiths, and other. artisans. Four

European and three native firms are engaged in coffee-curing. In

1903-4 coffee from above the Ghats to the value of 41 lakhs was

exported. Coir yarn is manufactured in considerable quantities in the

Amindlvi Islands, where it forms a Government monopoly, and along

the coast.

On the coast, too, a considerable industry exists in fish-

curing, which is done with duty-free salt in fourteen Government

curing-yards. Most of the product is exported to Colombo, but large

quantities are also sent inland. Sandal oil is distilled in the Udipi

taluk from sandal-wood brought down from Mysore.

The principal articles of export are coffee, tiles, coco-nut kernels (copra), rice, salted fish, spices, and wood. The tiles are exported to Bombay and to ports in the Presidency. The coffee is brought from Mysore and Coorg to be cured, and is exported chiefly to the United Kingdom and France. The coco-nut kernels go chiefly to Bombay, rice to Malabar and Goa, and salted fish to Colombo. Large quantities of areca-nuts are shipped to Bombay and Kathiawar. The wood exported is chiefly sandal brought from Mysore and Coorg. The chief imports are cotton piece-goods, grain, liquor, oil, copra, pulses, spices, sugar, salt, and salted fish, largely to meet local needs, but partly for re-export to Mysore and Coorg.

The bulk of the trade is carried on at Mangalore (the commerce of which is referred to in the separate article upon the place); and Malpe, Hangarkatta, and Gangoli are the most important of the outports. The most prominent by far of the mercantile castes are the Mappillas, who are followed by Telugu traders, such as the Balijas and the Chettis. Konkani Brah- mans, native Christians, and Rajapuris also take a share. There are twenty weekly markets in the District under the control of the local boards.

The District had recently no railways ; but the Azhikal-Mangalore ex- tension of the Madras Railway, opened throughout in 1907, now affords communication with Malabar and the rest of the Presidency. Its con- struction is estimated to have cost 109 lakhs for a length of 78 miles. A line from Arsikere on the Southern Mahratta Railway to Mangalore has also been projected and surveyed.

The total length of metalled roads is 148 miles and of unmetalled

roads 833 miles, all of which are maintained from Local funds.

Avenues of trees have been planted along 467 miles. The main lines

are the coast road from Kavoy to Shirur ; the roads leading to Mercara

through the Sampaji ghat from Kasaragod and Mangalore ; and those

from Mangalore through the Charm&di ghat to Mudugere taluk, and

through Karkala and the Agumbe ghat to the Koppa taluk in Mysore.

Lines running through the Kollur, Hosangadi, Shiradi, and Bisale

ghats also afford access to Mysore, and the main routes are fed by

numerous cross-roads.

The tidal reaches of the rivers and the numerous backwaters furnish a cheap means of internal communication along the coast. In the monsoon communication by sea is entirely closed ; but during the fair season, from the middle of September to the middle of May, steamers of the Bombay Steam Navigation Company call twice weekly at Mangalore and other ports in the District Mangalore is also a port of call for steamers of the British India Company and other lines. Large numbers of coasting craft carry on a brisk trade.

Owing to the abundant monsoons the District always produces more grain than is sufficient for its requirements. It is practically exempt from famine, and no relief has ever been needed except in the year 1812.

Administrations

For administrative purposes South Kanara is divided into three subdivisions. Coondapoor, comprising the Coondapoor and Udipi . . taluks, is usually in charge of a Covenanted Civilian. Mangalore, corresponding to the taluk of the same name (but including also the Amindlvi Islands), and Puttur, comprising the Uppinangadi and Kasaragod taluks , are under Deputy-Collectors recruited in India. A tahsildar and a stationary sub-magistrate are posted at the head-quarters of each taluk, and deputy-taksildars at K&rkala, Bantval, Beltangadi, and Hosdrug, besides a sub-magistrate for Mangalore town.

Civil justice is administered by a District Judge and a Subordinate Judge at Mangalore, and by District Munsifs at Mangalore, Kasaragod, Udipi, Coondapoor, Puttur, and Kfirkala. The Court of Session hears the more important criminal cases, but serious crime is not more than usually common, and there are no professional criminal tribes in the District. Offences under the Abkari, Salt, and Forest Acts are numerous; and civil disputes are frequently made the ground of criminal charges, especially in connexion with land and inheritance, the majority of the Hindu castes in the District being governed by the Aliya Santana law of inheritance, under which a man's heirs are not his own but his sister's sons.

Little is known of the early revenue history of the District Tradi- tion gives one-sixth of the gross produce, estimated at first in unhusked and latterly in husked rice, as the share demanded by the government prior to the ascendancy of Vijayanagar. About 1336, in the time of Harihara, the first of the kings of that line, the land revenue system was revised. One-half of the gross produce was apportioned to the cultivator, one-quarter to the landlord, one-sixth to the government, and one-twelfth .to the gods and to Brahmans. This arrangement thinly disguised an addition of 50 per cent to the land revenue ; and the assumed share of the gods and Brahmans, being collected by the government, was entirely at its disposal.

In 1618 the Ikkeri Rajas of

Bednur imposed an additional assessment of 50 per cent, on all the

District except the Mangalore hobli, and at a later date imposed a tax

on fruit trees. These additions were permanently added to the stan-

dard revenue. Other additions were made from time to time, amount-

ing in 1762, when Haidar conquered Kanara, to a further 35 per cent,

of the standard revenue, but still not sufficient to affect seriously the

prosperity of the District. Haidar cancelled the deductions previously

allowed on waste lands and imposed other additions, so that at his

death the extras exceeded the standard revenue. The further exac-

tions and oppressions of Tipu were such that much land went out of

cultivation, collections showed deficiencies ranging from 10 to 60 per

cent., and the District was so impoverished that little land had any

saleable value.

Major (afterwards Sir Thomas) Munro, the first Collector of the District, setting aside all merely nominal imposts and assessments on waste lands, imposed on Kanara and Sonda (the present Districts of North and South Kanara) a new settlement in 17 99- 1800. Some slight reductions were made in the following year. It worked smoothly for some time ; then difficulty in the collections and signs of deteriora- tion owing to over-assessment induced the Board of Revenue to order a revision, based on the average collections from each estate since the country came under the British Government. This assessment, intro- duced in 1819-20, was till recently in force in South Kanara, with the exception of a portion of the Uppinangadi taluk which was subse- quently taken over from Coorg.

Continued difficulty in realizing the demand, owing to low prices and riotous assemblages of the cultivators, who refused to pay their assessment, led to a Member of the Board of Revenue being deputed in 1831 to inquire into the state of the District. He reported that the disturbances were due to official intrigues, that the assessment was on the whole moderate, though low prices had caused some distress, and that where over-assessment existed it was due entirely to the unequal incidence of the settlement, aggravated by the frauds of the village accountants, who had complete control over the public records. In accordance with his views, some relief was granted in the settlement for 1833-4 to those estates which were over- assessed. The Board did not, however, regard these measures as satisfactory.

Further correspondence confirmed the view that any attempt to base a redistribution of the assessment on the accounts then available was doomed to failure, owing to their fallacious nature. The Board therefore expressed the opinion that the only remedy was a settlement based on a correct survey. This proposal involved a con- sideration of the question whether any pledge had been given for the fixity of the settlement of 1819-20. After further correspondence between the Collectors, the Board, and the Government, the question was dropped in 1851, the improvement in prices having meanwhile relieved the pressure of assessment on particular estates.

In 1880 the matter was again raised by the Government of India, in connexion with the general revision of settlements in the Presidency ; and it was finally determined that the Government was in no way pledged to maintain the assessment unaltered, and that the survey and revision of settlement should be extended to Kanara in due course. A survey was begun in 1889 an d settlement operations in October, 1894. A scheme was sanctioned for all the taluks and has now been brought into operation. Under this the average assessment on ' dry ' land is R. 0-9-7 per acre (maximum Rs. 2, minimum 2 annas) ; on 'wet' land Rs. 4-7-1 1 (maximum Rs. 10, including charge for second crop; minimum 12 annas); and on garden land Rs. 4-13-7 (maximum Rs. 8, minimum Rs. 2). The proposals anticipate an ulti- mate increase in the assessment of the District of Rs. 9,22,000, or 65 per cent., over the former revenue.

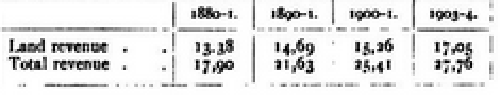

The revenue from land and the total revenue in recent years are given below, in thousands of rupees: —

Outside the municipality of Mangalore, local affairs are managed

by the District board and the three taluk boards of Coondapoor,

Mangalore, and Puttur, the areas in charge of which correspond

with the subdivisions of the same names. Their total expenditure in

1903-4 was Rs. 2,82,000, of which Rs. 1,57,000 was laid out on roads

and buildings. The chief source of income is, as usual, the land

cess. South Kanara contains none of the Unions which on the east

coast control the affairs of many of the smaller towns.

The police are in charge of a District Superintendent, whose head- quarters are at Mangalore. The force numbers 10 inspectors and 558 constables, and there are 50 police stations. Village police do not exist.

There is a District jail at Mangalore, and 8 subsidiary jails at the head-quarters of the tahsildars and their deputies have accommodation for 85 males and 35 females.

At the Census of 1901 South Kanara stood eleventh among the Districts of the Presidency in the literacy of its population, 5*8 per cent, (n-i males and 0.9 females) being able to read and write. Education is most advanced in the Mangalore taluk, and most back- ward in the hilly inland taluk of Uppinangadi In r 880-1 the number of pupils of both sexes under instruction in the District numbered 6,178; in 1890-1, 18,688; in 1900-1, 24,311; and in 1903-4, 27,684. On March 31, 1904, the number of educational institutions of all kinds was 658, of which 502 were classed as public and 156 as private. The public institutions included 474 primary, 23 secondary, and 3 special schools, and 2 colleges.

The girls in all of these

numbered 4,107, besides 1,566 under instruction in elementary private

schools. Six of the public institutions were managed by the Educa-

tional department, 85 by local boards, and 7 by the Mangalore

municipality, while 278 were aided from public funds, and 126 were

unaided but conformed to the rules of the department. Of the male

population of school-going age in 1903-4, 21 per cent, were in the

primary stage of instruction, and of the female population of. the same

age 4 per cent Among Musalmans, the corresponding percentages

were 30 and 6 respectively. Education, especially that of girls, is most

advanced in the Christian community.

Two schools provide for the education of Panchamas or depressed castes, and are attended by 37 pupils. The two Arts colleges are the St. Aloysius College, a first- grade aided institution, and the second-grade Government College, both at Mangalore. The former was established in 1880 by the Jesuit Fathers. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 2,22,000, of which Rs. 77,000, or 35 per cent, was derived from fees ; and 53 per cent of the total was devoted to primary education.

The District possesses 8 hospitals and 1 1 dispensaries, with accom- modation for 75 in-patients. In 1903 the number of cases treated was 135,000, including 1,600 in-patients, and 3,200 operations were per- formed. The expenditure was Rs. 38,000, which was mostly met from Local and municipal funds.

In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 28,000, or 23 per 1,000 of the population. Vaccination is compulsory only in the Mangalore municipality.

[J. Sturrock and H. A. Stuart, District Manual (1894).]