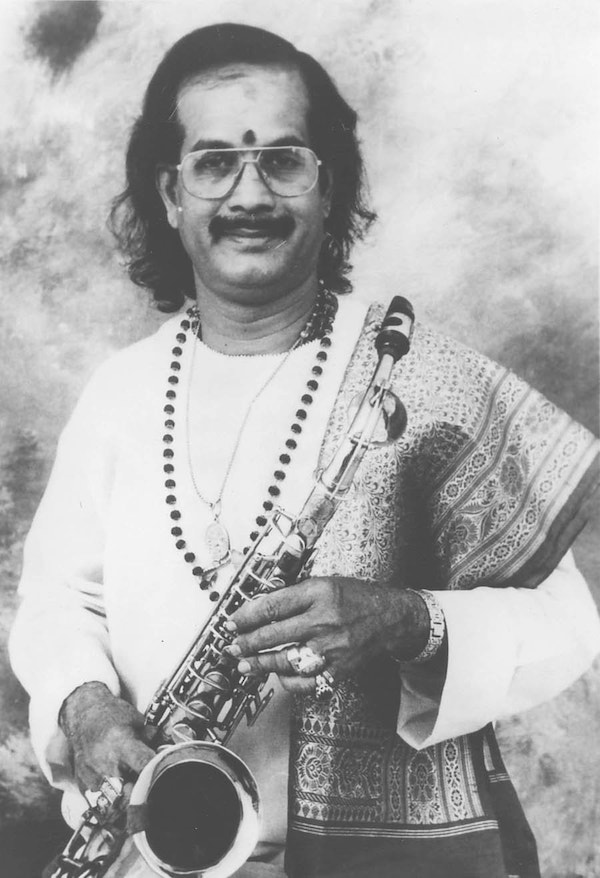

Kadri Gopalnath

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A brief biography

Giovanni Russonello, Nov. 4, 2019: The New York Times

From: Giovanni Russonello, Nov. 4, 2019: The New York Times

From: Giovanni Russonello, Nov. 4, 2019: The New York Times

From: Giovanni Russonello, Nov. 4, 2019: The New York Times

Kadri Gopalnath was a youngster growing up in a village in southern India when he first heard the alto saxophone at a performance by the Mysore Palace Band, a holdover from the years of British rule that mixed Indian and European repertoire.

The saxophone’s sound struck Kadri as something different from the penetrating drone of the nadhaswaram, the traditional double-reed instrument that his father played every day in the local temple, and that Kadri had been learning. The alto saxophone’s blooming quality felt exotic, and it drew him in.

With help from neighbors and attendees of the temple, his father pulled together money and sent away for a saxophone. But rather than learn traditional Western repertoire, Kadri set about interpolating the ragas (harmonic modes) and gamakams (ornaments and slurs) of classical South Indian music into saxophone playing. His main strategy was to adapt the vocal inflections of Indian singers to the instrument, though his sound was always redolent of the nadhaswaram’s pinched, scalding tone.

Mr. Gopalnath would eventually become one of the most prominent classical musicians in India, and the first to show on a grand scale how the saxophone, despite its Western-tempered tuning, could be a real asset in Carnatic music, not just a novelty.

His renown spread across the globe thanks to numerous albums (allmusic.com lists him as a leader on over 100) and frequent appearances at festivals in Europe and the Americas. He has been cited as an influence by such prominent jazz musicians as the New York-based alto saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa — who collaborated with Mr. Gopalnath on a widely celebrated album, “Kinsmen” (2008), and sometimes toured with him — and Shabaka Hutchings, a young British tenor saxophone star who brought him to the Le Guess Who festival in the Netherlands last year.

“He was such a revolutionary, in playing any kind of Indian classical music on the saxophone,” Mr. Mahanthappa said in a phone interview. “The vehicle of Indian music is the voice; it’s really hard to imitate that intonation and the sliding between notes.”

Nevertheless, by the time of Mr. Gopalnath’s death on Oct. 11, at 69, his legend was in place. “His name,” The Hindu newspaper said, “was a synonym with saxophone in the country.”

Mr. Gopalnath’s son Manikanth, a film composer and producer, confirmed the death, at a hospital in Mangalore, India. He did not specify the cause but said that his father had been ill for some time, and that after a back ailment rendered him unable to play the saxophone, he stopped eating.

“His life was about being onstage,” Manikanth Gopalnath said. “He decided to go.”

In addition to Manikanth, Mr. Gopalnath is survived by his wife, Sarojini Gopalnath; another son, Guruprasad; a daughter, Ambika Mohan; and six grandchildren.

Kadri Gopalnath was born in Sajipamuda, a village in the southwestern Indian state of Karnataka, on Dec. 6, 1949, the eldest of eight children. His father, Thaniyappa, earned only a modest living as a temple musician, while his mother, Gangamma, kept the home.

In an interview with The Hindu in 2012, Mr. Gopalnath reflected on the hardships of his early life. “I started out with nothing, right from ground level,” he said. “It was not easy for my father to bring up eight children. I look back on those fledgling days with a sense of surprise, awe.”

He began playing the nadhaswaram, studying under his father, but after switching to the saxophone in his adolescence he moved to Mangalore, Karnataka’s major port city, to pursue music on a broader stage.

Moving throughout southern India, he studied successively under three major gurus, including a fellow saxophonist, Gopalakrishna Iyer. The last and most consequential was T.V. Gopalakrishnan, an esteemed vocalist, mridangam drummer and violinist based in Chennai, where Mr. Gopalnath became prominent on the music scene.

His career had begun when, across the Atlantic Ocean, John Coltrane’s was coming to a close. Coltrane had transformed jazz in part by investigating Indian styles and bringing them into an American context through the tenor saxophone. Mr. Gopalnath went the other way: He listened to jazz instrumentalists for their technique and inspiration, but bent the instrument to more traditional Carnatic ends.

A performance at the 1980 Bombay Jazz Festival caused his star to rise across India. But he didn’t catch his big commercial break until 1994, when he recorded the soundtrack to “Duet,” a hit Tamil-language film whose protagonist was a saxophonist.

That year he also became the first Indian classical musician to perform at the prestigious BBC Promenade, and he soon began performing more often in festivals around the world, typically in combos with other stars of Carnatic music.

At home, he came to be known as India’s “saxophone chakravarti,” the Sanskrit term for a good king. In 2004 he was awarded India’s fourth-highest civilian award, the Padma Shri.

Throughout his adult life, he called the saxophone his “greatest love.” “I am just 65 years old, not yet tired of playing classical music and ragas on saxophone,” he told the website emirates247.com in 2015. “I have never counted the number of concerts or the number of hours spent playing saxophone, within and outside India, over five decades. I have traveled a long way in 50 years, and yet there is a long way to go in the world of music.”