Jimmy Engineer

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Jimmy Engineer

In tune with nature

By Marjorie Husain

The well-known artist and social worker, Jimmy Engineer, recently returned from travels to the USA, Berlin and Dubai, where he showed a limited edition of prints and spoke on the cultural aspects of Pakistan. The first exhibition took place in Washington at the Pakistan Embassy on March 21. From there he flew to Berlin where his work was shown for a week, before returning to Washington for further exhibitions.

“I have started travelling a lot,” says Jimmy, “There is such a distorted view of the country abroad. It seems the foreign media focuses on negative issues without showing the rich cultural aspects of Pakistan. In Germany and America I spoke in universities and on the radio and answered numerous questions. The audiences appeared very interested and were very responsive.”

Known as a ‘social crusader’ and an artist recognised through national awards, Engineer has, since the early nineties, taken on himself to ‘make a difference’; walking for causes, raising awareness on social issues, and exhibiting his work here and abroad. When asked about his feelings on his dual identity, Engineer declares he is first and foremost a Pakistani who loves his country, and he would rather be known as a good Pakistani than a good artist.

His aim now is to travel as much as possible, work for causes and talk about Pakistan: its great history, culture and the current art scene. Through the years he has taken up countless causes. He has traversed Pakistan on foot, living in villages, sharing the lives and problems of people of the interior, and he has created a wide awareness of these problems in the country.

Through Engineer’s efforts, clinics and schools have been erected, and his work for Special children is well known. Above all he loves to take the children out for ‘fun’ and takes great pleasure in their enjoyment. ‘Everyone should have some joy in life’, is his philosophy.

He has been instrumental in arranging assistance in hospitals, children’s homes and the young offender’s jail, visits to prisons, hospitals and institutions are part of his routine. Though his parents and siblings are settled in the USA, Engineer has made it clear, he will never leave Pakistan.

Painting is Engineer’s great solace, a time of peace and quiet and few people have visited his studio, a cool, pristine setting without the clutter of furniture. There one discovers centuries old tiles and objects, paints and brushes neatly arranged and ready for work.

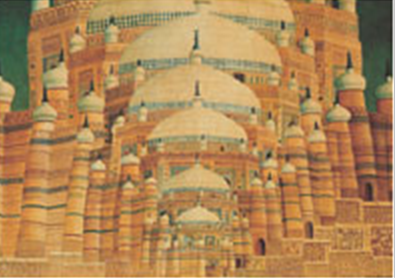

Some time ago I visited the studio and found four rooms, each one stacked with huge canvases; many as large as seven by five feet in height. Not surprising as he had trained as a muralist at the NCA and most of the work he has exhibited in the past has been on a grand scale. His work in the genre of landscape exudes an ambience of peace, nature and the lasting things of life. He has also painted beautiful, seascapes, still-life and portraits, which are carefully stored, but the work in process at that time was an extensive body of very large paintings with an architectural theme.

In the work he has detailed ancient seasoned brickwork, the decorative aspects of classic architecture, and myriad classic motifs and designs. In some of the paintings he has juxtaposed famous buildings from diverse countries and cultures as an allegory for ‘unity’; his personal message of peace and tolerance for all mankind. “My work is always positive, I do not believe in negative issues.” A follower of the Sufi philosophy, Engineer has painted multiple images of the Shah Rukn-e-Alam tomb in Multan, firmly believing that the rationalism of Sufism is rapidly spreading globally.

The final stage of his travels found him in Dubai. He spoke at length on the art activities in Dubai, where, he said, the local artists are promoted with respect. The plans for art underway appear very exciting, and he spoke of an exhibition of Picasso’s work shown in Abu Dhabi. “A lot is happening.” In May this year, Engineer’s limited edition of prints was shown at the Avari Hotel, creating considerable public and media response.

In exhibition, 65 artworks were displayed, out of which 30 carried an architectural theme, but the work was not for sale. “I just want people to visually enjoy my work, not to buy it.” Writer Enid Parker covered the exhibition for Khaleej Times, and Engineer told her: “I still consider my self to be a student.”

Jimmy Engineer is a man on the move, deriving energy as he says, “from nature,” and always on to the next appointment, wanting immediate results for his social work. This view point is in complete contrast to his art persona, where he has no thought of finishing the work in a hurry or pleasing a market. The world of art is Engineer’s retreat, and there he creates a world of his own where all is in harmony with nature.

Jimmy Engineer displayed an extensive body of very large paintings with an architectural theme

"The servant of Pakistan”

Jimmy described his wall paintings depicting Allama Iqbal’s masterpiece Javed Namah as his most difficult work, but also one of his major artistic achievements

“I have been sent here,” said an unfamiliar man, in a dark shalwar kameez, as he stood silhouetted in the doorway of my Karachi hotel room. It was late in the evening and he had insisted on seeing me personally and alone, an unnerving demand in 1997, when the filming had just started on my film Jinnah. There was a storm of controversy and the film, its cast, and crew were being attacked in the media. We were taken to court and a case was instituted to shut down production. Although we won the case, commentators speculated whether the entire enterprise would collapse mid-way.

It is in this context that the man’s words sounded inspirational to me. “From now on,”he said, “I will be by your side and will escort you to your plane when the film is completed. You will succeed despite the opposition.”

The man was Jimmy Engineer, one of the most famous painters and social activists of Pakistan.

Jimmy, a Zoroastrian, hinted that a “transcendental power” had sent him. He presented a video cassette to me and insisted that I watch it. In the darkly-lit sequence filmed with a hand held camera, Jimmy was seen entering a cave and there was a cage containing two lions. At first, the lions were agitated, but they calmed down eventually.

“talking to people, showing my work and telling them that we are not all extremists. We are artists, lecturers, doctors and scientists. It became my mission to travel all over the world creating a positive image of Pakistan.” — Jimmy Engineer

“Your position is quite similar to what has been shown in the film. You too are facing ferocious lions in a cage. But I have been sent to be by your side, and in the end, you will accomplish your mission.”

True to his word, throughout the long and difficult shooting in Karachi and Lahore Jimmy was by my side. He even walked from Karachi to Lahore on a one-man crusade to raise funds, after the government reneged on its agreement to contribute funds for Jinnah. As he had promised, he ultimately saw me off at the Karachi airport.

Jimmy’s Parsi community immigrated to the Subcontinent from Persia in the seventh century. There are fewer than 1,800 Parsis in Pakistan today with fewer than 190,000 in the world total, he told me. The Zorastrians have a tradition where one’s profession is reflected in their name, so Jimmy’s last name was given because his father and grandfather were engineers, although he did not end up pursuing their careers.

Jimmy was born in Loralai, Balochistan, in 1954. At the age of only six, doctors told his family that his kidneys were failing and that he had only three months to live. Three months later, however, he was still alive and the doctors informed his family his kidneys appeared “brand new.” It was, his family said, a “miracle” and Jimmy believes he was given a second chance. “I’m trying to repay God through my work,” he said in 2009, “I don’t refuse anyone if they need help.”

He went on to study at St. Anthony High School and at the National College of Arts, both in Lahore, and became a professional painter in 1976. A theme running through his work has been universal compassion for all people, especially the poor and down trodden. Jimmy has produced over 3,000 paintings-which have sold for as much as 1.6 million pounds-and more than 1,500 drawings and 1,000 calligraphies. 700,000 of his prints are held in private collections in over 60 countries. His drawings and paintings encompass many genres including abstracts, human figures, animals, landscapes, calligraphies, seascapes, religious, historical, and philosophical works, and still-lifes.

“As I grew up,” Jimmy elaborated in an interview in Sri Lanka’s Daily News, “I became a student of nature. You are dealing with the perfect master then, because nature is perfect while we are imperfect….”

Jimmy described his wall paintings depicting Allama Iqbal’s masterpiece Javed Namah as his most difficult work, but also one of his major artistic achievements. Jimmy explained that he was invited to paint Javed Namah by Iqbal’s son. Iqbal had written a letter to his son,Jimmy said in 2012,”that he would like some artist to create a visual display of the philosophy in the poem. There were two or three great painters from other countries who tried their hand at the deed. They were only able to paint one scene not the whole thing. I went through his letter and discovered that he had written that the man who paints ‘Javed Nama’ will have a great name in the world”. When Iqbal’s son, came to ask Jimmy when the work would be finished, Jimmy said that”I would tell him that his father too comes to me asking that question.”

Jimmy has held over 80 art exhibitions in Pakistan and around the world. “I have traveled all over the world,” he said in 2013, “talking to people, showing my work and telling them that we are not all extremists. We are artists, lecturers, doctors and scientists. It became my mission to travel all over the world creating a positive image of Pakistan.”

He is keenly aware of this importance in the west. “Whenever I show my work in Europe or the United States,”Jimmy said in 2009 in Houston, Texas,”it changes the mind of people when they look at it. For a moment they forget that I’m from Pakistan. They feel that I’m part of the international community, and it helps change their perception and image of my country, which is often negative.” Jimmy’s father, as it turns out, is a prominent religious leader based in Houston, where there is a distinguished Zoroastrian community. Among its members is the famous Pakistani novelist Bapsi Sidhwa.

In 2017, Jimmy exhibited his artwork in China at the prestigious Zhengyangmen Museum in Beijing. The exhibit was entitled, “Art, Culture and Heritage of Pakistan” and included his striking and moving painting “The Last Burning Train of 1947,” which depicts the impact on refugees during the horrific violence that befell the Subcontinent during Partition. The painting is part of a series of paintings on canvas depicting the human tragedy of Partition.

Jimmy has additionally led more than 100 walks for social causes, arranged over 140 awareness programs for handicapped and orphaned children, and donated 700,000 prints of his work to charity.

When I asked him who inspires him, he told me, demonstrating his embrace of other religions, that he was “a close disciple of Sufi Barkat Ali of Faisalabad,” and “I accepted all religions as my personal belief.” Invoking Zarathustra of his Zoroastrian faith, Jimmy elaborated on his philosophy, “Our Prophet taught us three words. Good Words. Good Thoughts. Good Deeds.”

This philosophy comes through in his painting that he presented to me as a gift when he met me in Washington, D.C. It is a large work of calligraphy of the shahada, and I have it proudly displayed in my office. When guests come and ask about it, I point out that it is by one of Pakistan’s most famous painters who is not a Muslim, and they are invariably surprised.

Jimmy has received many awards from all over the world, including The National Endowment of the Arts Award in the United States in 1988 and the Sitara-e-Imtiaz for Art from the Government of Pakistan in 2005. Despite these numerous accolades, he says, “I call myself the servant of Pakistan. That is the only title I am proud of.”

The writer is the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at American University, Washington, DC, and author of Journey into Europe: Islam, Immigration, and Identity