Inheritance of property: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The basics

Wife, daughter, mother: Women’s inheritance rights

RIJU MEHTA, August 5, 2019: The Times of India

Riju Mehta, August 20, 2019: The Times of India

From: RIJU MEHTA, August 5, 2019: The Times of India

From: RIJU MEHTA, August 5, 2019: The Times of India

It has never been a good time to be a woman, especially when it comes to inheritance and property rights. “Till as late as the formulation of the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, the law was blatantly biased against women,” says Rohan Mahajan, Founder & CEO, LawRato.com. “It was only after the amendment in the Hindu Succession Act in 2005 that it became more balanced,” says Raj Lakhotia, Founder & Director, Dilsewill.com, an online will-maker. Since gender neutral inheritance laws and increase in awareness among women are the need of the hour, we list here the inheritance rights of women, be it a wife, daughter or mother.

WHAT ARE YOUR RIGHTS?

HINDUS

The Hindu Succession Act, 1956, governs the succession and inheritance laws for Hindus, along with Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs. The Act makes no distinction between movable and immovable property. It only applies to intestate succession (where there is no will) and to anyone who converts to Hinduism. It has no application in case of testamentary succession (where there is a will).

“The property owned by a person can be classified only as ancestral or self-acquired. Ancestral property is one that is inherited up to four generations of male lineage without any division, and the right to share in it is accrued by birth,” says Rajesh Narain Gupta, Managing Partner, SNG & Partners, Advocates & Solicitors. Self-acquired property is bought by the person with his own resources or through property acquired from his share in an ancestral property. “For self-acquired property, the father enjoys unfettered discretion to will it to anyone he wishes,” says Lakhotia. When a man dies without a will, it devolves to four categories of heirs—Class I, Class II, Agnates (if two people are related by blood or adoption wholly through males) and Cognates (related to the intestate by blood or adoption but not wholly through males). The first preference is to Class I heirs.

Wives: A wife is entitled to an equal share of her husband’s property like other entitled heirs. If there are no sharers, she has full right to the entire property. A married Hindu woman is the sole owner and manager of her assets whether earned, inherited or gifted. She is also entitled to maintenance, support and shelter from husband, and if staying in a joint family, from the family.

If the couple is divorced, all issues related to maintenance and alimony are ordinarily decided at the time of divorce, and the wife does not have any right in husband’s estate if he dies intestate. “If during the lifetime of the first wife, the husband remarries without a divorce, the second marriage will be void. The second wife will not inherit anything and rights of the first wife will not be affected. However, kids from second marriage will get a share along with other legal heirs,” says Rajesh Mahindru, Advocate, Delhi High Court. In case of an inter-faith marriage, the wife is entitled to inheritance as per the personal laws of the husband’s religion.

Daughters: “Section 6 of the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, was amended in 2005 to end discrimination against women,” says Mahajan. As a result of this amendment, a daughter has an equal right to ancestral property as a son and her share in it accrues by birth. Before 2005, only sons had a share in such property. So, a father cannot will such property to anyone he wants to, or deprive a daughter of her share in it.

If the father dies intestate, all legal heirs have an equal right to the property. Class I heirs have the first right and these include the widow, daughters and sons, among others. Each heir is entitled to one part of the property, which means that a daughter has a right to it too.

Before 2005, the Hindu Succession Act considered daughters only as members of the Hindu Undivided Family (HUF), not coparceners. The latter are the lineal descendants of a common ancestor, with the first four generations having a birthright to ancestral or self-acquired property. However, after marriage, she was not considered a member of HUF. After the amendment, the daughter has been recognised as a corparcener and her marital status makes no difference to her right.

A daughter also has the same rights as a son to the father’s property irrespective of her date of birth, that is, before or after 9 September 2005. On the other hand, the father should have been alive on 9 September 2005 for the daughter to stake a claim over his property. If he had died before 2005, she will have no right over the ancestral property, and self-acquired property will be distributed as per the father’s will.

Mothers: As a mother is a Class I heir, she is entitled to an equal share of property of her predeceased son. A widowed mother is entitled to maintenance from her children who are not dependants.

MUSLIMS

For Muslims, inheritance laws are governed by personal law. There are four sources of Islamic law governing this area—the Quran, the Sunna, the Ijma and the Qiya. When a man dies, both males and females become legal heirs, but the share of a female heir is typically half of that of male heirs. While twothirds share of the property devolves equally among legal heirs, one-third can be bequeathed as per his own wish.

Wives: A wife without kids is entitled to one-fourth the share of property of her deceased husband, but those with kids get one-eighth share. If there is more than one wife, the share may reduce. In case of divorce, her parental family has to provide maintenance after the iddat period (about three months).

Daughters: “A son always takes double the share of a daughter, but the latter is the absolute owner of inherited property,” says Lakhotia. In the absence of a son, the daughter gets half the share of inheritance. If there is more than one daughter, they collectively receive twothirds of the inheritance.

Mothers: A mother is entitled to onethird share of her son’s property if the latter dies without any children, but will get a one-sixth share if he has children.

CHRISTIANS

Christians are governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925, specifically by Sections 31-49. Under this, the heirs inherit equally, irrespective of the gender.

Wives: If the husband leaves behind both a widow and lineal descendants, she will get one-third share of his property, while the remaining two-thirds will go to the descendants. If there are no lineal descendants, but other relatives are alive, half the property will go to the widow and the rest to the kindred. If there are no relatives, the entire property goes to the wife. A man can legally marry a second time only after the death of the first wife or after divorcing her. If he has a second wife even as his first wife is alive or not divorced, the second wife or kids have no right over his property. However, the kids of a legally divorced wife have an equal share in the property as that of the second wife and her kids.

Daughters: A daughter has an equal right as her brother to father’s property. She also has full right over her personal property upon attaining majority.

Mothers: “If a person dies without a will and has no lineal descendants, then after deducting his widow’s share, the mother is entitled to an equal share as other surviving entitled sharers,” says Lakhotia. These sharers could be the brother, sister, or the widow of such sibling, or the children of any predeceased siblings.

HOW IS INHERITANCE TAXED?

“There is no inheritance or gift tax if the property is inherited from a relative or is acquired through a will. On sale of property that has been inherited, capital gains tax is applicable,” says Lakhotia. “Once inherited, any source of income, such as rent or interest, is transferred to the new owner and he must pay tax on it,” says Mahajan. Tax is levied on capital gains on the sale of inherited property. The gain is based on the period for which the property is held by the owner. If held for more than 24 months, it is treated as a long-term gain. This also includes the period for which it was held by the previous owners. If it is less than 24 months, the actual cost of acquisition and improvement are deducted and the balance is treated as a short-term gain and taxed as per the tax slab applicable to the owner or transferer. If the combined holding period exceeds 24 months, the transferer has the right to deduct the cost of acquiring and improvement, while adding the rate of inflation to cost for the holding period. Then the tax is levied as per the applicable rate.

IF YOUR RIGHTS ARE DENIED

If a woman does not get her due share in ancestral property, she can send a legal notice to the party denying her the right. If restrained from seeking her claim, she can file a suit for partition in a civil court. She can also seek partition of properties occupied by other legal heirs. “If physical partition is not possible, the court can auction the properties to give the woman her share,” says Mahindru. “To ensure the property is not sold during the pendency of the suit, she can seek a court injunction,” says Mahajan. If it is sold without her consent, she can add the buyer as a party in suit if she has not instituted a suit yet, or can request the court to add the buyer as a party if the suit has been filed.

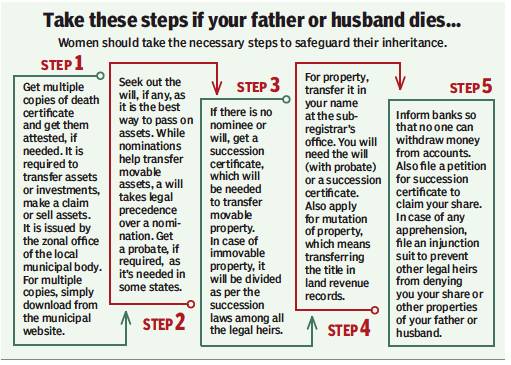

Take these steps to safeguard your inheritance if your father or husband dies…

1. Get multiple copies of death certificate and get them attested, if needed. It is required to transfer assets or investments, make a claim or sell assets. It is issued by the zonal office of the local municipal body. For multiple copies, simply download from the municipal website

2. Seek out the will, if any, as it is the best way to pass on assets. While nominations help transfer movable assets, a will takes legal precedence over a nomination. Get a probate, if required, as it’s needed in some states.

3. If there is no nominee or will, get a succession certificate, which will be needed to transfer movable property. In case of immovable property, it will be divided as per the succession laws among all the legal heirs.

4. For property, transfer it in your name at the sub-registrar’s office. You will need the will (with probate) or a succession certificate. Also apply for mutation of property, which means transferring the title in land revenue records.

5. Inform banks so that no one can withdraw money from accounts. Also file a petition for succession certificate to claim your share. In case of any apprehension, file an injunction suit to prevent other legal heirs from denying you your share or other properties of your father or husband.

Daughters’ rights

Riju Mehta, May 15, 2019: The Times of India

Consider a situation where you’ve been married young, without much education or earning potential, and end up being harassed by your husband and his family. To make matters worse, your parents are not very keen to support you and the brothers don’t want to give you a share in the ancestral property. What do you do?

Financial dependence, be it on the father, brothers or husband, has been at the root of much hardship for women over the years. It was with the idea of levelling this playing field that the Hindu Succession Act 1956 was amended in 2005, allowing daughters an equal share in ancestral property. Despite this, can your father deprive you of your share in the property? Find out...

IF PROPERTY IS ANCESTRAL

Under the Hindu law, property is divided into two types: ancestral and self-acquired. Ancestral property is defined as one that is inherited up to four generations of male lineage and should have remained undivided throughout this period. For descendants, be it a daughter or son, an equal share in such a property accrues by birth itself. Before 2005, only sons had a share in such property. So, by law, a father cannot will such property to anyone he wants to, or deprive a daughter of her share in it. By birth, a daughter has a share in the ancestral property.

IF PROPERTY HAS BEEN SELF-ACQUIRED BY FATHER

In the case of a self-acquired property, that is, where a father has bought a piece of land or house with his own money, a daughter is on weaker ground. The father, in this case, has the right to gift the property or will it to anyone he wants, and a daughter will not be able to raise an objection.

IF FATHER DIES INTESTATE

If the father dies intestate, that is, without leaving a will, all legal heirs have an equal right to the property. The Hindu Succession Act categorises a male’s heirs into four classes and the inheritable property goes first to Class I heirs. These include the widow, daughters and sons, among others. Each heir is entitled to one part of the property, which means that as a daughter you have a right to a share in your father’s property.

IF DAUGHTER IS MARRIED

Before 2005, the Hindu Succession Act considered daughters only as members of the Hindu Undivided Family (HUF), not coparceners. The latter are the lineal descendants of a common ancestor, with the first four generations having a birth right to ancestral or self-acquired property. However, once the daughter was married, she was no longer considered a member of the HUF. After the 2005 amendment, the daughter has been recognised as a coparcener and her marital status makes no difference to her right over the father’s property.

IF DAUGHTER WAS BORN OR FATHER DIED BEFORE 2005

It does not matter if the daughter was born before or after September 9, 2005, when the amendment to the Act was carried out. She will have the same rights as a son to the father’s property, be it ancestral or self-acquired, irrespective of her date of birth. On the other hand, the father has to have been alive on September 9, 2005 for the daughter to stake a claim over his property. If he had died before 2005, she will have no right over the ancestral property, and self-acquired property will be distributed as per the father’s will.

Why it is HINDU SUCCESSION ACT AND NOT INDIANS SUCCESSION ACT. Here also appeasement politics...because may be, MUZZIES MARRY HINDU GIRL and utter TR...

HOW THE HINDU SUCCESSION ACT CAME INTO BEING

Prior to 1956, Hindus were governed by property laws which varied from region to region and in some cases within the same region, from caste to caste.

The Mitakshara school of succession which was prevalent in most of north India, believed in the exclusive domain of male heirs. In contrast, the Dayabhaga system did not recognise inheritance rights by birth and both sons and daughters did not have rights to the property during their father's lifetime. At the other extreme was the Marumakkattayam law prevalent in Kerala which traced the lineage of succession through the female line.

Former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru's administration championed the cause of women's right to inherit property and despite resistance from orthodox sections of Hindus, the Hindu Succession Act was enacted and came into force on on June 17, 1956.

Many changes were subsequently brought about that gave women greater rights but they were still denied the important coparcenary rights. The act was eventually amended in 2005, with daughters being recognised as coparceners, giving them an equal share in ancestral property.

Parents and eviction of adult children

July 29, 2019: The Times of India

Can parents evict adult children?

Yes, they can, but kids may retain legal claim over parental

For Indian parents conditioned by culture, it has always been difficult to snap the umbilical cord with progeny even in adulthood. This is the reason adult children stay with their parents till they get married and, sometimes, even afterwards. While the arrangement works well as long as it is based on mutual respect and financial understanding, it often sours under the glare of greed or friction caused by proximity. What if the fissures widen beyond repair? Can the parents ask their children to move out? Find out.

’’’ 1 When children can from the their parents house evict ?

Adult children can live with parents in their house only till the time the latter want them to. In 2016, the Delhi High Court ruled that ‘a son, irrespective of his marital status, has no legal right to live in his parents’ house, and can reside there only at their mercy’. However, if children are abusive, parents have a blanket right to evict them. This is as per the rulings of various high courts in cases involving senior citizens, who appealed to the courts on being harassed by their kids. The eviction holds for married or unmarried son, daughter, even son-inlaw or daughter-in-law.

2 Does self-acquired the property ? have to be

In 2017, the Delhi High Court ruled that the elderly parents who are abused by children can evict them from any type of property, not just a self-acquired one. The property can even be ancestral or rented, as long as parents are in its legal possession. This is an improvisation of the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act 2007, which specified that the kids could be evicted only from a self-acquired property.

3 Do parental evicted property children ? have a legal right over

Even if the parents evict a child from their house, there is no legal concept of disowning an adult child in India. In case of a self-acquired property, the parents can disinherit a child by cutting him out of the will. However, in case of an ancestral property, the parents have no control since the child has a right to it by virtue of birth and they cannot cut the kid out of the property’s ownership in a will. If a parent dies intestate, the self-acquired property will go to the legal heirs. So, even if the parent-child relationship is bad and the child has been evicted, he can acquire the property as a legal heir.

4 What’s the procedure for evicting?

An elderly parent can file an application to the Deputy Commissioner or District Magistrate to evict abusive children. In Delhi, the application is forwarded to the Sub-Divisional Magistrate, who has to send the report with final orders within 21 days. If the property is not vacated within 30 days, the DC can have it evicted forcibly. As per a high court ruling, the Senior Citizens Maintenance Tribunal also has the power to order the eviction of children.

Adopted children

Have no right to genitive family properties

August 15, 2023: The Times of India

Bengaluru : An adopted son cannot continue to exercise rights as a coparcener in his genitive family, the Kalaburagi bench of the Karnataka high court has observed in a recent judgment. Dismissing the regular second appeal filed by Bheesmaraja, a resident of Secunderabad, Justice CM Joshi has pointed out that in M Krishna vs M Ramachandra and in another case, the HC had already held that on adoption, the adoptee gets transplanted into the family that adopts him with the same rights as that of a natural-born son, and such transfer of the adopted child severs all his rights with the family from which he was taken in adoption. “It was categorically heldthat he loses the right of succession in genitive family properties,” the judge added.

Son of Pandurangappa Ellur and Radhabai, Bheesmaraja was given in adoption to Hyderabad-based couple P Vishnu and P Shantabai. The adoption deed was executed on December 22, 1974; at that time, Bheesmaraja was 24 years old. His biological father died in 2004.

Thereafter, in the very same year, he moved the Raichur court for partition. He argued that the adoption was without his consent and was prohibited under the provisions of Section 10 of the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956. His mother, sister and brother resisted his claim, saying he was a consenting party to the adoption, and the suit was dismissed on December 10, 2007. OnJanuary 22, 2010, Bheesmaraja’s appeal, too, was dismissed. Challenging both orders, he moved the HC, reiterating he is a coparcener in his genitive family and, therefore, had an existing right in family properties.

On the other hand, his mother, brother and sisters, and the children of his deceased brother, Ashokraj, argued that in the Arya Vysya community, to which they belong, adoption of a person aged more than 15 is allowed.

“If we accept the contention of the counsel for the appellant herein, it would lead to a situation whereby an adopted son would continue to be exercising rights as a coparcener in the genitive family as well as the adoptive family. Therefore, this contention at any rate cannot hold good,” the judge noted.

Disputed paternity

Can’t force paternity test/ SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Oct 2, 2021: The Times of India

In an important judgment, the Supreme Court has ruled that courts cannot force DNA test on one of the siblings, who are engaged in a civil suit, for crystallising inheritance rights as it has the possibility of stigmatising a person as a “bastard” and violating his right to privacy, which is part of right to life.

Three daughters of a Himachal Pradesh couple requested a trial court, where their brother had filed a suit for a declaration that he was the sole inheritor of their parents’ properties, to subject their ‘brother’ to DNA test while claiming that he was not the biological son of their parents, which disentitled him from inheriting their parents property. The man refused to undergo a DNA test. The trial court dismissed the application saying he can’t be forced to undergo the blood test. But, the HC reversed the decision and asked the man to take a DNA test.

On appeal, a bench of Justices R S Reddy and Hrishikesh Roy said, “In a case like the present, the court’s decision should be rendered only after balancing the interests of the parties, that is, the quest for truth, and the social and cultural implications involved therein. The possibility of stigmatising a person as a bastard, the ignominy that attaches to an adult who, in the mature years of his life is shown to be not the biological son of his parents may not only be a heavy cross to bear but would also intrude upon his right of privacy”.

Referring to the ninejudge bench decision in K S Puttaswamy case that had given right to dprivacy the status of a fundamental right being part of right to life, the bench said, “When the plaintiff is unwilling to subject himself to the DNA test, forcing him to undergo one would impinge on his personal liberty and his right to privacy”.

Writing the judgment, Justice Roy said DNA is unique to an individual (barring twins) and can be used to identify a person’s identity, trace familial linkages or even reveal sensitive health information. “Whether a person can be compelled to provide a DNA sample can also be answered considering the test of proportionality laid down in the unanimous decision of this court in K S Puttaswamy case, wherein the right to privacy has been declared a constitutionally protected right,” he said.

Referring to the dispute in hand, the bench said, “In such a kind of litigation, where the interest will have to be balanced and the test of eminent need is not satisfied, our considered opinion is that the protection of the right to privacy of the plaintiff should take precedence.”

The SC said the plaintiff, without subjecting himself to a DNA test, is entitled to establish his right over the property in question, through other material evidence.

Women

Ancestral assets of spouses

Uttarakhand gives rights

Kautilya Singh, February 20, 2021: The Times of India

U’khand women to get rights on ancestral assets of their spouses

Dehradun:

The Uttarakhand government has brought an ordinance that will give co-ownership rights to women in their husband’s ancestral property, reports Kautilya Singh.

The landmark decision by the government has been made keeping in mind the large-scale migration of male members from the state in search of work.

Through this, the government aims to provide economic independence to the women who are left behind in the hills and are solely dependent on agriculture to meet their financial needs. Chief Minister Trivendra Singh Rawat said Uttarakhand is the first state in the country to do so.

The amendment made to the Uttarakhand Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act is expected to benefit around 35 lakh women in the state.

‘Won’t remain land co-owner if she remarries’

In revenue records, the wife’s name will now be mentioned as co-owner. “This is the biggest reform of our government. I’m confident that it will not be limited to Uttarakhand and other states will follow it,” Rawat said.

As per the ordinance, in case a woman files for divorce and marries someone else, she will not be regarded as co-owner of the land owned by her first husband. But, if her divorced husband is unable to bear her financial expenses, she would be allowed co-ownership. Besides, if a woman divorces and does not have a child or her husband has been missing for a period of over seven years, she can also become co-owner of land that her father owns. In the past 10 years, close to 5 lakh people moved out — 50% of them in search of work. Many villages are left only with elderly couples and women. In such a scenario, the women — in the absence of jobs — are involved in household chores and working in fields without any ownership rights.

Widows’ rights After remarriage

July 5, 2021: The Times of India

The Chhattisgarh high court has said that a widow loses right to property inherited from her late husband if she marries again in the manner recognised under the law.

“The effect of valid remarriage would be the widow losing her right to property inherited from her husband,” Justice Sanjay K Agrawal held in his order on June 28, while emphasizing that disinheritance could follow only in the cases of marriages which are legally valid. “Unless the fact of remarriage is strictly proved after observing the ceremonies required, as per Section 6 of the Act of 1856, remarriage cannot be said to be established by which the right to property, which is a constitutional right, is lost that too by widow,” ruled Justice Agrawal.

Section 2 of the Hindu Widows Remarriage Act that a widow would lose her rights in deceased husband’s property after on her marriage The case before Justice Agrawal pertained to a dispute over whether the “remarriage” of the widow at the centre of the dispute had taken place in the manner provided for under the law. Section 6 of The Hindu Widows Remarriage Act says that all the ceremonies and rites that make a marriage valid apply also to a “valid” widow’s remarriage.

The circumstances of the property dispute date to pre-Independence days. The property at the centre of the dispute originally belonged to a man named Sugriv, who had four sons --Mohan, Abhiram, Goverdhan and Jeeverdhan. Mohan died childless, Goverdhan had one son, Loknath, so too Abhiram, whose son, Ghasi, died in 1942.

The case centred around Ghasi’s share of the property. Loknath – who is now dead – had moved court, arguing that Ghasi’s widow Kiya Bai had entered into a second marriage in 1954-55 in ‘chudi’ form, so she ‘ceased to have any interest in the property’ and that the authorities had erred in recognizing her as the owner of the property in question.

In certain sections of Chhattisgarh society, it was the custom earlier that if a man gives bangles (chudi) to an unmarried woman or widow, it is deemed to be marriage. Opposing the suit, Kiya Bai and her daughter filed a joint statement that the tehsildar had entered their names on the revenue record in 1984 in accordance with the law, and there is no illegality therein. They said Kiya had never remarried and the civil suit should be dismissed.