Indians in the Gulf

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

An overview

Indian population in the Gulf; economic relations

From: June 7, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

Indian population in Gulf countries; economic relations, all presumably as in 2021 or thereabouts

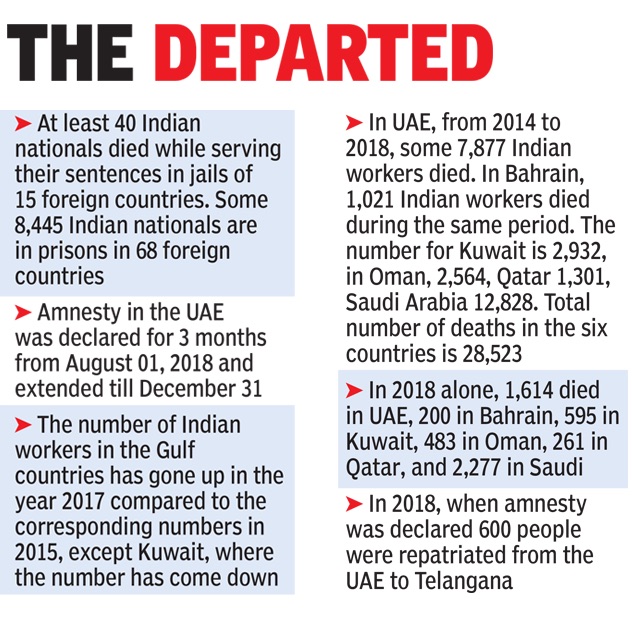

Death of Indian workers in the Gulf

2014-18

Raising serious questions about the safety of Indian labourers working in the Gulf countries — Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — the external affairs ministry said 28,523 Indians working as labourers in these nations died there between 2014 and 2018.

To a question by Lok Sabha member from Patiala, Dharamvira Gandhi, minister of state for external affairs, VK Singh, said according to data compiled by Indian embassies in these countries, most deaths were from Saudi Arabia where 12,828 unskilled Indians died since 2014, followed by United Arab Emirates where 7,877 died till 2018.

Hundreds from Telangana die in the Gulf every year

U Sudhakar Reddy, January 29, 2019: The Times of India

From: U Sudhakar Reddy, January 29, 2019: The Times of India

A 24-year-old tribal farmer Ganesh Badhavath of Kottakortula Tanda in Nallavelli in Nizamabad district ended his life in Bahrain on January 13, by hanging himself, 20 days after his legal migration on a work visa. He leaves behind his pregnant wife and a two-year-old daughter. Debts due to failed borewells, money paid to the agent who obtained visa, and the stress of staying away forced him to take the extreme step.

Ganesh’s father Devi Singh told TOI, “All the four borewells dug in the one acre of land owned by Ganesh failed. He could not pay his debt of Rs 3 lakh. Ganesh had paid Rs 60,000 to an agent and got a visa in December 2018. He left for Bahrain on December 18 after being recruited by a Tamil Nadu-based agency and started working in Almoran as a cleaner for Rs 18,000 salary per month. He was able to get a visa as he had been there earlier, and had returned. We didn’t get Rythu Bandhu for the land, and Ganesh was not eligible for Rythu Bima as the land is an assigned land according to government officials.”

Ganesh’s story is not an isolated case, as lakhs of people migrate for a meagre salary of Rs 10,000 to Rs 25,000 depending on the country. The cost of living in most Gulf countries is high. Telangana is one of the top five states reporting a large number of deaths due to suicide, work site accidents, road traffic accidents and cardiac arrests. As many as 28,523 Indians died in six Gulf countries + in the past four years.

Cheated in their search of a better life

They mostly belong to Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Rajasthan, Punjab, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. Most deaths are reported from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Harsh conditions, debts, cheating by agents, and family issues back home are the main reasons behind the suicides. Officially, as per 2017 statistics, as many as 22.53 lakh workers are living in the Gulf.

Telangana NRI wing official, E Chitti Babu, told TOI, “Since July 2014, we have officially helped to get around 518 bodies, where we offer free ambulance service to shift the bodies from the airport to their hometown for Below Poverty Line families. Unofficially, another 100 bodies may have arrived. Of these cases, around 30 are suicides. Most deaths are attributed to heart attacks due to harsh weather conditions, lack of proper food and sleep. In some cases, where a person injured in road accident gets admitted to hospital and dies, the hospital authorities declare it as cardiac arrest. This is done to avoid the payment of compensation of Rs 15 lakh, for which the worker is eligible.”

2014-19: 33,988 Indians died

U Sudhakar Reddy, Nov 22, 2019: The Times of India

From: U Sudhakar Reddy, Nov 22, 2019: The Times of India

Replying to a question from Congress MP and TPCC president N Uttam Kumar Reddy in the Lok Sabha, minister of state for external affairs V Muraleedharan said a majority of deaths of Indians were reported from Saudi Arabia and the UAE. On average, 15 Indian immigrants die every day in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman and the UAE.

HYDERABAD: On an average, 15 Indian immigrants die every day in six countries — Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) — in the Gulf. According to a data of the ministry of external affairs (MEA), 33,988 Indians have died in the Gulf since 2014, including 4,823 this year.

Replying to a question from Congress MP and TPCC president N Uttam Kumar Reddy in the Lok Sabha, minister of state for external affairs V Muraleedharan said a majority of deaths of Indians were reported from Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Telangana NRI wing official E Chitti Babu said Telangana is one of the states in India which account for a large number of deaths. “We believe around 1,200 from Telangana may have died in the Gulf in the past five years,” he told TOI.

Curiously, the Telangana government’s NRI wing maintains death records of only those where a free ambulance is provided to the families. Babu said that 850 families of below poverty line have availed the free ambulance service for shifting bodies of their kith and kin from Shamshabad airport to their villages and towns.

Till October this year alone, MEA had received 15,051 complaints from Gulf NRIs, mostly pertaining to cheating by agents on employment. Muraleedharan told the Lok Sabha that most of the complaints received from Indian workers are over non-payment of salaries and denial of legitimate labour rights and benefits such as non-issuance/renewal of residence permits, non-payment/grant of overtime allowance, weekly holidays and longer working hours.

“Refusal to grant exit/re–entry permits for visit to India, refusal to allow the workers to return to India on final exit visa after completion of their contracts and non-provision of medical and insurance facilities and not being paid compensation upon death are some of the other complaints,” he added.

The return of migrants from the Gulf

1998-2018; early 2020

Rajeev KR, May 24, 2020: The Times of India

From: Rajeev KR, May 24, 2020: The Times of India

Factors that make Indians return from the Gulf

From: Rajeev KR, May 24, 2020: The Times of India

From: Rajeev KR, May 24, 2020: The Times of India

The Gulf returnee was a stock figure in the Malayali imagination: often satirised as a guy with flashy clothes, a gold chain and dark glasses, his suitcases bursting with consumer goods. In places like Dubai or Sharjah or Muscat too, they formed a subculture of their own, watching Malayali movies, keeping up with the news, socialising with each other.

This mobility and prosperity reshaped homes and villages, as wealth came with prestige. As political scientist Devesh Kapur wrote in his study of migration, the diaspora often plays an insurance role — so when disaster strikes Kerala, as it did with floods, their support has been a source of resilience.

There have been spots of trouble for Indians in the Middle East — the Lebanese crisis in 2006, the Iraq war, the Nitaqat nationalisation drive in Saudi Arabia. In 1990, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait stranded many Indians. But those events were geographically limited, and people could go to other destinations. This time, the crisis is global, and there are no safe shores anywhere. says migration expert S Irudaya Rajan of the Centre for Development Studies (CDS), who is a member of the state’s expert committee on Covid- 19. “It is going to be the largest mass return of Keralites since people from the state started chasing their petrodollar dreams in wooden dhows in the early 1970s. We expect around 2-3 lakh non-resident Keralites (NRKs) to return by December,” he says Shameer* is one among the 60,000 expats from Kerala in the UAE who have lost their jobs. A salesman at a company in Fujairah, UAE for the last four years, the 32-year-old got his termination letter last month. His pregnant wife had been visiting from Kerala, but her flight back home was suspended, and she was forced to deliver the baby at a private hospital there. Shameer has no insurance, and bills to the tune of 12,000 AED (Rs 2.4 lakh). He’s had to leave his residency permit at the hospital as he frantically tries to raise money through social workers.

“The hospital won’t release the birth certificate without the money, which means I can’t get a passport for the baby and send my family home,” he said. He plans to make a last-ditch attempt to find a job in the UAE, though the chances are slim. Expats fear both loss of livelihood and disease as they crowd in their homes and labour camps, says Easa Anees, a Sharjah-based Malayali social worker and partner at a legal firm. “We were flooded with queries on Facebook from distressed Keralites, who wanted advice on issues like sudden termination, unpaid salaries, visa issues and so on,” he says.

Kerala’s migration to the Middle East began in the 1970s, as rising oil prices and the economic boom in the Gulf created the need for overseas labour. Keralites formed the majority among Indian migrants, in terms of numbers and remittances. Now, every fourth Indian in the Gulf is Malayali. There are 18.9 lakh emigrants in the six GCC countries, as of 2018. No wonder Keralais spooked at the massive turn of the tide. Most of the migrants to the ‘Gelf ’ (in local lingo) were often semi-skilled workers without long-term contracts or visas who made money and came back, though middle-class professionals and businesspeople are also part of the diaspora. Muslims, Christians and Hindus have all shared in the story. This movement has been a sweeping economic and social force in Kerala: some claim it reduced poverty more effectively than any agrarian reform, union activity or social legislation. In 1980-81 at the peak, Gulf revenues were over a quarter of Kerala’s GDP. Even now, remittances from NRKs are estimated at Rs 85,000 crore a year, according to the Kerala migration survey.

Despite its sluggish industrial and agricultural performance, this money made Kerala a high spender for decades. It is the reason the state has four international airports, and the landscape is an almost unbroken stretch of small towns and cities, with large homes belonging to expats.

However, the diaspora dream has faded in the last decade because of declining wages, nationalisation policies in many GCC countries and changing demographics. There was a drop of about three lakh emigrants between 2013-18. Now, of the three lakh expected to return because of the corona outbreak, CDS estimates that one lakh will have no savings and will be more desperate for government help. Another lakh will be returning migrants who might have come back anyway, and will have savings that can be channelled into investment opportunities. The remaining third would migrate again, said Rajan.

Today, Kerala is facing its biggest-ever financial crisis; a Gulati Institute of Finance and Taxation (GIST) study predicts the state’s economy will shrink by 10.13% even if normalcy is restored after three months of lockdown. “With remittances down, there will be a sharp recalibration; it could lead to an economic crisis and social problems. If returning expats are not adequately rehabilitated, there could even be suicides. Kerala should brace for a change in spending habits,” Rajan said.

The state hopes to tackle reverse migration with its self-employment scheme that aims to create new expat ventures. “We also plan to integrate returnees into new sectors that will emerge in the post-Covid situation, such as healthcare, says K Harikrishnan Namboothiri, CEO of Norka Roots, nodal agency for NRKs.

Some hope there is a silver lining. State Planning Board member K N Harilal suggests it could help get rid of the ‘Dutch disease’, an economic phenomenon where a large inflow of foreign currency impacts sectors like agriculture and manufacturing by pushing up land prices and unskilled wages. “Land prices are already coming down,” he says. But for Keralites, the impulse to migrate may not be so easy to forget. “Malayalis are addicted to it, they will keep moving,” says Rajan.

The migrant experience in Malayalam cinema

Malini Nair, Migrant experience comes alive on screen, in stories, May 24, 2020: The Times of India

In that evergreen Malayalam comedy, Nadodi Kaattu (1987), two credulous chumps dreaming of a better life in ‘Gulf ’ are conned into taking a motorboat going to “California, via Dubai”. They swim ashore the next morning to what they think is the land of gold and opportunities but is actually Besant Nagar beach in Chennai. They stumble around in Arabi kuppayam (abaya) and mouth nonsense ‘Arabic’ — ‘Biste u hi hes tilevaha?’ ‘Isava, ua’ — till they spot a Chennai bus and realisation dawns. We had guffawed at the bumbling duo but knew in our hearts that the desperation of Malayali job-seekers packed into dhows and despatched across the Arabian Sea in the 1960s, the visa rackets, and soured dreams were all too real. And whether you knew any Gulf migrant or not, the many cultural forms that drew richly from the migration experience told us their stories through literature, films and music.

LETTERS FROM NEGLECTED WIVES: In this age of WhatsApp and Zoom, it may have nothing more than anthropological value, but in the 1970s, ‘Dubai kathu paatu (letter songs)’ were a rage. These were lyrical letters of longing — a lot like the Bidesiya songs in Bhojpuri — sung in quivering voices where women told their husbands of loneliness, passing youth, the empty conjugal bed and children who only knew their fathers through photo albums. A sense of morbid doom usually swamped these letter songs. ‘Can I see your face before I die? Or join you in Abu Dhabi with its camels and lovely sunsets?’ The songs written with all the formalism of old-fashioned letters — starting with ‘Bahumanapetta priya bhartave (respected dear husband)’ and ending with ‘And I now close the letter’ — were still oddly touching . The story goes that the king of the form, S A Jameel, was a family counsellor privy to intimate emotional outpourings of Gulf spouses. And that these letter-song cassettes were traded by separated couples to express feelings they couldn’t articulate.

‘SUIT, RAYBANS AND NATIONAL PANASONIC’: Mammooty starrer Pathemari (dhow) in 2015 recreated the early adventures of the 1960s: the dangerous journey on dhows, the backbreaking work and the heartless family back home sponging off the sacrifices of men starved of family love. “What do they know back home? All they see is a man getting off a flight — the suit, ‘Raybon’ cooling glasses, foreign cigarette… and of course the National Panasonic in one hand”... the illusion of Gulf glory was dissected for the first time in Vilkanundu Swapnangal (dreams for sale, 1980) written by M T Vasudevan Nair. Later, the migrant hero, now an arriviste puffed with money and arrogance, returns home to find he is a misfit everywhere. These two films bookend an array of celluloid migrant stories, including the visually delectable Perumazhakkalam (2004, later made in Hindi as Dor) and at least two films with political subplots. Varavelpu (1989) was the tragicomic story of a jobless Gulf migrant returning home, dreaming of love and mango pullisseri, only to be faced with a money-grubbing family. He sets up a small transport business that union bullies scupper; forcing his return to the harsh marubhumi (desert). Arabikatha did the reverse: sent hardcore leftist ‘Cuba’ Mukundan to the Gulf to teach him that humanism is above ideology.

DESERT STORIES: If you get the ‘zimbly’ jokes, you get why each of Deepak Unnikrishnan’s short stories in Temporary People is a ‘Chabter’ and why there is one story dedicated to a ‘Fone’. The evocative and funny book is authored by a second generation of ‘temporary people’ whose experience is more confident and less homeward-looking than most such writing. The biggest Gulf saga so far is Aadujeevitham or Goat Days (2008) by Benyamin, about a hapless jobseeker caught in a slave racket that lands him in a remote Saudi desert ranch. The famous book soon to be a movie, incidentally, stranded the Prithviraj-led film crew in Jordan through the pandemic.

Year-wise trends

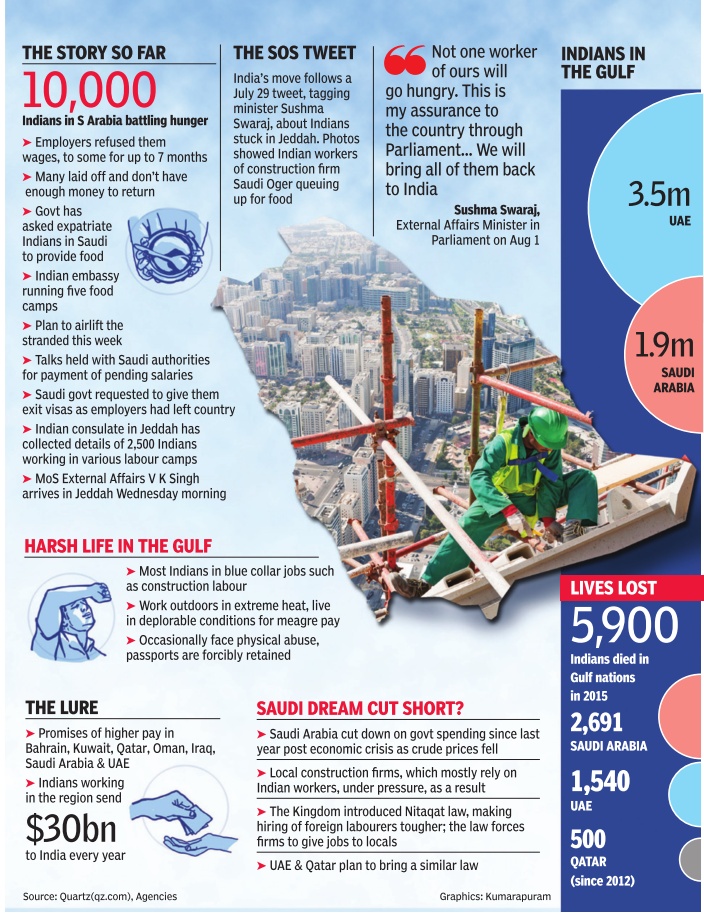

2015-16: the status of Indians in the Gulf

See graphic:

2015-16: the status of Indians in the Gulf

2019: Workers from Africa, Philippines replace Keralites

Shenoy Karun, March 11, 2019: The Times of India

A weakened economy of the Middle East and protectionist measures of the Indian Government results in the displacement of Indian labourers, especially the Malayalis in the Gulf, say experts in migration.

“The economy of Gulf hasn’t picked up after the global crisis. There is some recovery but haven’t got back to the pre-2008 level. They were trying to recover through World Cup, Dubai Expo 2020 and Saudi Arabia Vision 2020, but they are yet to reach the pre-2008 stature, said S Irudaya Rajan of Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. The wages haven’t gone up. But people from other countries like Nepal or the Philippines are ready to work for low wages, thus edging out Malayalais. I had met some Nepali labourers in Qatar, who are working for $200 (Rs 14,000) per month,” he said.

According to him, the salary of teachers in the Philippines was so low that they were coming to the Middle East to work as housemaids.

“This led to a situation where the Philippine Government had to match the teachers’ salary with that of housemaids in the Gulf to bring them all back,” he pointed out.

“Africa is becoming a big threat to Indian labourers, especially Malayalis,” said Majeed Abdulla, chairman of Resource Hunters, which supplies human resources to the Middle East.

“They have multi-skills and their language skills are also good, prompting firms to hire them. And they demand only a little above 50% of what you typically pay to an Indian worker,” he said.

The displacement is happening in professions like drivers, helpers and store workers.

“While Indian drivers demand more than Rs 20,000 per month, the African counterparts work for the equivalent of Rs 8,000 per month. Similarly, while Indian security staff demand Rs 30,000 the Africans are willing to work for Rs 20,000 per month,” Abdulla said.

A second factor for the displacement of Indian workers is the higher minimum wage fixed by the Indian government, said a Mumbai-based recruiting agency.

For example, the Indian embassy in Saudi Arabia has published the referral wage of unskilled workers as SR 1,500 (close to Rs 30,000). For the local Arab households and businesses, this proves to be expensive, because, apart from this the employer must provide food, accommodation, transportation, medical insurance, uniforms, paid leave and return ticket for the worker.

A third factor is the attempt of the Gulf countries to maintain a demographic balance. It also acts against the hiring of Indian/Malayali workers.

See also

Indians in the Gulf

Non-resident Indians (NRIs): Kerala

Indians in the Gulf