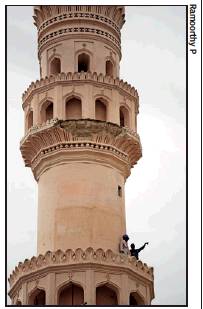

Hyderabad: Charminar

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

A foundation monument, and more

Rahul V Pisharody, April 30, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Rahul V Pisharody, April 30, 2023: The Indian Express

Charminar was built by the fifth ruler of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, Mohammed Quli Qutb Shah, who moved the capital of his kingdom out of Golconda Fort by building a new city to the south of the river Musi

One of the inner arches on the north-eastern minaret of Charminar – Hyderabad’s first-ever building constructed in 1591 – has a strange face carved in lime stucco that evades the public eye and evokes curiosity when one learns about it. It is the face of a cat which stands apart from thousands of intricate designs on the monument that continues to charm visitors even 430 years later. As it goes, in the absence of any conclusive evidence, one of the theories suggests that the cat’s face was carved in honour of the felines that kept the population of rats down and commemorates the end of a plague that ravaged the walled city of Golconda in the 16th century.

While there is hardly any reference to the cat’s head in historical texts, author Khwaja Owais Qarni illustrates the cat’s head in his graphic publication ‘Qarni’s Sketches of Hyderabad’ and describes it as “a design on the pinnacle of an interior arch in Charminar. The cat’s head in it is said to be a symbol of the monument’s identity”. Prof Salma Ahmed Farooqui, Director, H K Sherwani Centre for Deccan Studies, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, says the overcrowded city of Golconda was devastated by an epidemic in the 16th century and whether it was cholera or plague that led to the deaths is still debatable.

“The ‘plague’ of the 16th-century fortified city of Golconda is quite an understudied area with very little detail available,” says Farooqui. “While there are figurines like pigeons, peacocks, parrots, squirrels, and griffins here and there, the cat face is present only in one place and that becomes intriguing. That is why it is linked to the plague and why Charminar was built to commemorate the end of the plague. It is a legend,” says Prof Farooqui.

Golconda: Devastated by an epidemic

“While there are figurines like pigeons, peacocks, parrots, squirrels, and griffins here and there, the cat face is present only in one place and that becomes intriguing. That is why it is linked to the plague and why Charminar was built to commemorate the end of the plague. It is a legend,” says Prof Farooqui. According to her, the overcrowded city of Golconda was devastated by an epidemic in the 16th century and whether it was cholera or plague that led to the deaths is still debatable.

The iconic monument Charminar was built by the fifth ruler of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, Mohammed Quli Qutb Shah, who moved the capital of his kingdom out of Golconda Fort by building a new city to the south of the river Musi. Charminar is believed to have been built as the epicentre of the new city.

A public square here, called Jilukhanah or present-day Char Kaman, with four independent archways and a water fountain Char-su-ka-hauz or today’s Gulzar Hauz in the middle, led to four highways. This square was built as a replica of Maidan-i-Naqsh Jahan of the central Iranian city of Isfahan. According to historians, the city itself was designed by Minister Mir Momin Astarabadi – a minister of the Golconda Sultanate – as Safahan-i-Nawi, literally meaning new Isfahan.

Charminar, not just a foundation monument

A former director of archaeology and official in the Nizam government, Syed Ali Asgar Bilgrami, quotes the 16th-century manuscript ‘Tazuke Qutb Shahi’ to talk about the construction of Charminar in his 1927 book ‘Landmarks of the Deccan’. Notably, Bilgrami refers to cholera instead of plague when talking about the creation of Hyderabad city. “Owing to the outbreak of Cholera, the inhabitants fixed a huge Tazia in the heart of the city on Thursday, 1st Moharrum 999AH, so that it may serve as a charm to safeguard them from the epidemic, and when it subsided, the huge building of Charminar was constructed of stone and mortar at the same place,” he quotes from ‘Tazuke Qutb Shahi’.

Bilgrami refers to the Charminar as a prototype of a Tazia or Taboot, which is the representation of the tomb of Imam Hussain, the grandson of Prophet Mohammed. However, it was not just a foundation monument. He says the first storey was used as a madrasa with chambers for students while the second storey was a mosque.

More interestingly, a water reservoir here used to get water from as far as the Jalpalli tank, over 8 km away, and water was distributed to the inhabitants of the city and the royal palace from here. Quoting French traveller Thevenot, who visited the city 66 years after its foundation, M A Qaiyum, in his book ‘Charminar in Replica of Paradise’, says, “all the galleries of the building (Charminar) seem to make the water mount up to that it be conveyed to the King’s Palace and reach its highest apartments.”

Noted historian Dr M A Nayeem, in his book ‘The heritage of the Qutb Shahis of Golconda and Hyderabad’, elaborates on the foundation of Hyderabad while hinting at the aforementioned 16th-century epidemic. Nayeem, who authored over 25 books on the Deccan, quotes the Persian manuscript Tawarik-i-Qutb Shahi to say, “Insanitary conditions in Golconda resulted in epidemics, like plague and cholera”.

Nayeem quotes Abdul Qadeer Khan Bidri in another manuscript ‘Ahwal-i-Tarikh-i-Farkunda’, “decimated by pestilence, the nobility of Golconda submitted a petition to the Sultan for building a new city. The Sultan graciously acceded to the request. And the Puranapul (bridge) built earlier in 1578 by his father, Ibrahim, showed the way to the side where the extension of the capital would take place.”

He says the reign of Muhammad Quli was marked by the blossoming of the kingdom in the fields of art, architecture and literature and Charminar as the centre of the city with the Char Kaman was planned as an architectural replica of paradise.

The legend of Bhagmati and Bhagyanagar

The story of the origin of Hyderabad is, however, incomplete without the controversial reference to Bhagmathi, Baghnagar or Bhagyanagar. One of the historical accounts is that of Bilgrami in his book ‘Landmarks of the Deccan’ in which he says, “Sultan Muhammad Quli’s sweetheart Bhagmati, resided in the Chichlam village which is now called Shah Ali Banda and the City of Bhagnagar was styled after her name, but after her demise, it was denominated Hyderabad and seven years after the completion (1597) of the city, Farkhunda Bunyad (meaning foundation of fortune or luck) became its chronogrammatic epithet.”

This argument in connection with Bhagmati has been contested by a large number of historians. Renowned historian Prof Haroon Khan Sherwani wrote in his book that “there is no evidence in contemporary and near-contemporary sources” linking Bhagmati to the name of the city. According to historians, Sultan Muhammad Quli himself named the new city ‘Haiderabad’ (city of Haider) after the title of the fourth Caliph of Islam Hazrath Ali and refers to the city in one of his poems as “Shahre Hyderabad”. Nayeem says the city was referred to as Bagh-nagar (city of gardens) by some Mughal historians and European travellers like Francois Bernier, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier and Jean de Thevenot.

Nayeem argues that there is no mention of Bhagmati or Bhagyanagar in the historic record ‘Tarikh-i-Muhammad Qutb Shahi’ which was completed during the reign of the ruler. The legend is also not attested from epigraphic or numismatic evidence as all coins of the era mention either Darus-Saltanat-Golconda or Darus-Saltanat-Hyderabad. There are no monuments, inscriptions or even a tomb of Bhagmati. He says three local contemporary chronicles ‘Tarikh-i-Muhammad Qutb Shahi’, ‘Hadiqat-us-Salateen’ and ‘Hadaiq-us-Salateen’ have not mentioned Bhagmati or Bhagyanagar even once.

Fabled Charminar

Amarnath K. Menon , Faulty Towers “India Today” 1/9/2016

Come the holy month of Ramadan and Hyderabad unfailingly spruces up its iconic Charminar. Even roads radiating from the monument are shut on two days - jummat ul vida (the last Friday of the month) and on Eid - for the faithful to offer prayers, transforming the area into a hallowed precinct. For the rest of the year, though, the graceful granite, lime and mortar masterpiece is a glorified traffic island except for the odd 'monument' reference on the crackling city traffic police wireless network.

Yet, for all the neglect, traffic chaos and pollution, the Charminar is still one of the biggest draws for those visiting the city. Way back in 1993, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), its custodian, and the local civic authorities had initiated measures, in what was billed as the Charminar Pedestrianisation Project (CPP), to decongest the area and make its environs a tourist-friendly plaza. But for over a decade, the CPP was a project on paper, and thereafter a slow work in progress. Successive governments have done their best to stall the CPP, mostly at the behest of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM), which is opposed to the relocation of shops and streetside vendors, necessary to give the area some aesthetic appeal. Then, in 2010, after AIMIM chief Asaduddin Owaisi inaugurated the project, work gathered pace only to be interrupted by local activists of the party in connivance with businessmen and touts, who have encroached onto the four approach roads.

Now, in a big shift, after the ruling Telangana Rashtra Samithi captured the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) in February this year, K.T. Rama Rao, son of the Telangana chief minister K. Chandrasekhara Rao, has decided to implement the CPP vigorously as part of efforts to "rebrand Hyderabad".

But the task has only grown more formidable. Much of the earlier work has come to naught. Most shops, particularly on the westward road from Charminar to the lacquer bangles market of Lad Bazaar, have once again been edged forward onto the road (shopkeeprs had parted with some land earlier hoping the CPP's early completion would help their businesses). Towards the north, the four arches around the Gulzar Houz fountain, known as Char Kaman, have again been encroached upon and are in serious disrepair. To the south, the road leading to Mecca Masjid continues to be clogged with pushcart vendors and street hawkers. It is only to the east, leading to the Sardar Mahal, that the widened road is relatively free of encroachers.

The plying of vehicles and the digging for PWD work has ruined portions of the natural granite road and the paver blocks on the kerbs that are to serve as walkways. The stone arch facade on both sides of the road from the north has also lost its appeal, with shopkeepers having painted it in all sorts of colours. The Charminar itself has been the victim of monumental neglect, except for the occasional coat of lime plaster to conceal the warts and scars on what was built as an architectural marvel by Mohammed Quli Qutb Shah in 1591 to commemorate the founding of the city. The ASI has worked tirelessly, but even then, the stucco work and lime and mortar have paled or peeled off, blackening its surface in many sections. Pollution has been a big culprit, more so as the minar serves as a traffic roundabout. "The conservation of Charminar is a continuum, all stakeholders have to be on the same page. A monument needs breathing space in keeping with its visual integrity," says Nizamuddin Taher, superintending archaeologist, ASI.

Rama Rao knows the odds. "We want to introduce battery-operated autorickshaws to address the transport concerns while minimising pollution. We also need more tourist facilities-food courts, parking and toilets. We are meeting all the stakeholders and sorting out issues in a phased manner," says the minister, admitting that, "[absolute] cooperation is a must for the project to come to fruition." Though he has publicly declared that the CPP will be completed by October, it appears unlikely now.

The CPP is up against huge challenges. Some property owners are still holding out with stay orders from courts, refusing to surrender land to widen the inner and outer ring roads through which all vehicular traffic flows (the plan is to leave a 5,000 square metre buffer zone around the monument). The land acquisition process is a constant irritant for the GHMC. Eleven properties along the 2.3 km Inner Ring Road and 18 skirting the 5.4 km Outer Ring Road remain to be acquired. "[The] widening of the Inner Ring Road to 40 feet and Outer Ring Road to 60 feet is to ensure that all polluting vehicles keep a minimum distance of 100 metres from the Charminar," says GHMC commissioner B. Janardhan Reddy. Then there are the small masjids and temples that have to be relocated to allow free vehicular flow.

AIMIM chief Owaisi says, "[Building] the multi-storeyed parking lot, restoring the stone arches along Pathargatti and having uniform-sized signboards in common colours and material are important to develop it tastefully, conforming to international standards." But he is also adamant on the issue of street hawkers. "It's in line with the national policy of protecting their livelihoods, [as well as] appreciating them as being part of the local ethos," he says. But completing the CPP, besides offering a full view of the monument from a distance, would also mean that the area will have to be free of hawkers. Until a deadline is fixed to realise these aims, the Charminar will continue to suffer, and remain a blot on the city's claims of caring for its heritage.

2019: minaret damaged

moulika kv, May 3, 2019: The Times of India

From: moulika kv, May 3, 2019: The Times of India

Charminar suffers damage after chunk of minaret falls off

Hyderabad:

The iconic 428-year-old Charminar suffered damage, after a portion of the ornamental stucco work from one of its four minarets came crashing down, raising fresh concerns over its structural stability.

After a huge crack developed on the monument in 2018, conservationists suspected it to be the result of water-logging on its first-floor balcony.

“The stucco work that fell off comprises three different designs of lotus petals, balustrades and flowers,” said V Gopal Rao, conservation assistant of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

“The structure is several centuries old and that could be a reason for its weakening exteriors,” said Rao while also hinting at the possibility of low percentage of calcium in the lime stone being used to restore Charminar, resulting in the the recent damage.

The ASI will take up necessary repairs expected to be completed in a month’s time.

On the brink of danger

Charminar, the soul of Hyderabad, needs to be saved

Mir Ayoob Ali Khan,TNN | Sep 7, 2014 The Times of India

The Charminar is the Telangana state emblem.

The ageing historic Charminar structure is under attack from a growing volume of vehicular traffic around it and an alarmingly high level of pollution that are together inflicting debilitating blows on its foundation and the building itself.

The iconic building remains on the brink of danger.

The Charminar Pedestrianisation Project (CPP) was conceived with the stated objective of protecting the monument by creating new lifelines in the entire heritage precinct and reducing pressure on those that have aged and become narrow. But the implementation of the project has been so painfully slow that instead of providing relief it has become a burden now.

To restore Charminar to its past glory, all its stakeholders—the residents, business community, hawkers, and regular pedestrians—have to be taken on board. At the same time GHMC needs to be declared the nodal agency for CPP with no other government being allowed to take up any work in the precinct, without clearance from the civic body.

The fact that the CPP has become dated should be taken into account and accordingly revised with the help of experts from within and outside the city. Inputs from public representatives should also be taken seriously. Incidentally, the MIM which has been accused in the past of blocking the implementation of the CPP has come out openly in its support. The detailed meeting of GHMC officials with MIM floor leader Akbaruddin Owaisi, Charminar MLA Ahmed Pasha Quadri and Mayor Majid Hussain held recently is reflective of the same.

MIM insiders say that the party is keen on ensuring the completion of the CPP in the next couple of years as it has started to believe that the entire precinct would not only become an attractive tourist destination but also turn into a bigger business hub, once the project is finished.

Some businessmen who have expressed concerns about the implementation of the project in its present form feel that rushing its implementation without revising the plan would sound the death knell for business in the area. In fact, one among them pointed out how the once buzzing cloth market near Madina Junction is already dying, courtesy the chaotic traffic that has become a deterrent for shoppers.

They believe, when the road from Madina Junction to Charminar is closed down for vehicular traffic, as has been envisaged by in the CPP, the outer ring road from Darushifa to Hari Bowli would not be able to bear the additional load of traffic. Thus, GHMC planners will have to come up with an alternate arterial road plan. Moreover, shutting down the Madina Junction-Charminar road, without providing transportation for shoppers, would be like closing down the entire market, traders rue.

But intelligent planning, these businessmen add, could open up new avenues around Charminar and facilitate expansion of establishments, particularly on the Khilwat Road leading to Chowk, Moosa Bowli and Hussaini Alam.

What the CPP also needs to focus on is on creating a network of roads, to facilitate traffic mobility without causing inconvenience to the public and provide ample parking space. A multi-level parking area has been identified in Khilwat.

[Between the mid-1990s and 2014] the GHMC has been able to lay cobble stone only on one side of Charminar up to Sardar Mahal. Three other sides remain as bad as they were before.