Great Indian Bustard

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Characteristics

The great Indian bustard can easily be distinguished by its black crown on the forehead contrasting with the pale neck and head. The body is brownish and the wings are marked with black, brown and grey. Males and females generally grow to the same height and weight but males have larger black crowns and a black band across the breast. They breed mostly during the monsoon season when females lay a single egg on open ground. Males have a gular pouch, which helps produce a resonant booming mating call to attract females and can be heard up to a distance of 500 metres. Males play no role in the incubation and care of the young, which remain with the mother till the next breeding season. These birds are opportunist eaters. Their diet ranges widely depending on the seasonal availability of food. They feed on grass seeds, insects like grasshoppers and beetles, and sometimes even small rodents and reptiles.

Location

Shrishtee Bajpai, January 17, 2019: The Hindu

From: Shrishtee Bajpai, January 17, 2019: The Hindu

The GIB prefers grasslands ecosystem to survive (the most threatened and neglected ecosystem). But, their primary habitat is being diverted for industries, mining, and intensive agricultural practices. With a meagre population of 150 GIB’s remaining, we must act urgently to protect their habitat — the grasslands.

Rajasthan: Desert National Park

Shrishtee Bajpai, January 17, 2019: The Hindu

The Great Indian Bustard is one of the heaviest flying birds. Sadly, it is now on the endangered list as more and more of its habitat is disappearing.

A desert teeming with wildlife, including a bird almost as tall as a human? I could never imagine this, till I got the chance to go to Desert National Park near Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. Spread over 3000 sq km, this Park hosts one of the heaviest flying birds in the world — the endangered Great Indian Bustard (GIB), besides other wild animals.

It was my first visit to a desert ecosystem, full of sand and stones. Incredibly, this National Park has fossil evidence dating back to the Jurassic Period (180 million years ago) when it apparently had a hot and humid climate characterised by dense forests … so different from now!

After almost missing on sighting the desert cat, we were more alert when it came to look for the GIB. Meanwhile, we came across many raptors (birds of prey) perched on distant trees or soaring above us.

A sighting

Back in our guest house before the evening safari, our afternoon rest was pleasantly interrupted when a friend signalled to come out and pointed to a spiny-tailed lizard feeding on the shrubs. We noticed its stout tail with numerous protective spines. In a couple of minutes, it became aware of us and quickly ran into its burrow, a hole in the sand. We kept waiting for Mr. Spiny to come out but it wasn’t in the mood. Locally called sanda, they are significant prey for mammals and many raptors. However, due to excessive poaching (some people think their oil has medicinal properties!) they are threatened.

Even after such extraordinary sightings, we were looking forward to spotting the GIB. It was almost at the end of our evening safari and we had heard enough bustard tales, but had as yet no sighting. I was quite anxious, imagining how I should position my camera that I could get the best shot of this shy bird. All of us were distracted when our guide whispered ‘bustard’. Sure enough, we sighted one but as we got close, it flew away before I could take a picture. Our return to the rest house was filled with high anticipation as we hoped to spot another GIB. Unfortunately, it did not happen. But, I was still happy to get a glimpse of a species that might be the next bird on the list to become extinct in India.

Status

Flying into Extinction

Prerna Singh Bindra , Flying into extinction “India Today” 22/1/2018

The death blow to the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard (GIB) may come from unexpected quarters - renewable energy projects. As 2017 drew to a close, one GIB crashed against a power transmission line, one of the few remaining that criss-cross its last stronghold- the Thar desert in Rajasthan. Its burnt, ravaged carcass was found the next day, making it the ninth GIB to be killed by a transmission line, mainly of wind power, in the past decade. In July 2017, for instance, a GIB collided with a 33 KV transmission line connected to wind turbines in Naliya, Gujarat. With fewer than 150 birds remaining in the wild, each death takes the bird closer to extinction. In such low populations, even one unnatural death can cause extinction over three generations. Renewables, while critical as a clean source of energy, are not necessarily green, which is something India needs to consider as it pushes ahead with its ambitious renewable energy generation target of 175 GW by 2022, of which 160 MW is expected to be met via solar and wind energy. Worldwide, wind turbines kill between 150,000 and 320,000 birds. In Thar, a recent survey showed that five birds of various species-including endangered vultures-die per kilometre of power line every month. That translates to 18,700 birds across the landscape. Bustards are particularly vulnerable due to their narrow frontal vision-they spot the line when it's already too late. Such deaths are preventable. Low wattage power lines such as the one in Naliya can be undergrounded, and bird flight diverters on power lines have known to cut mortality by half in some European countries. But there has been little interest in India, either on the part of the power companies or the state to instal these due to the high costs involved.

Beyond the carnage, there is also the loss of habitat, solar and wind power being very land intensive. Prime bustard habitats between Naliya and Bitta in Kutch as well as the two main populations in Thar-in the northern part of the Desert National Park and the other at the Pokhran Field Firing Range-are packed with transmission lines and wind and solar power projects. Recognising the threat, the National Green Tribunal has passed an interim order barring new wind projects around the Desert National Park.

The way forward is decentralised renewable energy, harnessed by mini grids. Solar panels on rooftops need to replace the heavily polluting diesel generators that add to Delhi NCR's pollution burden and most residential colonies and corporate houses rely on.

Power lines are just one among the many threats the GIBs face. The bird has vanished from nearly 95 per cent of its historical range. Its habitat has been lost to roads, highways, mining, canals-as well as 'greening' projects that transform arid grasslands to wooded areas, rendering them hostile to the GIB. The Great Indian Bustard is endemic to India. In fact, it was to become our national bird but for the worry that its name might be misspelt! A few birds have been recorded in Pakistan-they fly between the two countries as they inhabit border regions-but hunting is a major concern here. One study shows that of the 63 birds sighted in four years (2001-04), 49 were poached. Better coordination between both countries has been suggested by forests officials and conservationists on both sides of the border. Another need of the hour to save the GIB is coordination with the army. As per sources, about half of the GIB's hundred-odd population in Thar resides within the field firing range in Pokhran. While the firing and explosives tested here remain a threat, what the GIB gets here-this being a protected army enclosure-is habitat undisturbed by mining, roads or other anthropogenic pressures. The forest department in Rajasthan has sought permission from the army for joint monitoring of the GIB.

It's only apt that both India's 'green army' and the one that protects its borders work together to protect the nation's endangered natural heritage from imminent extinction.

2002-2016

Listed in Schedule I of the Indian Wildlife (Protection)Act, 1972, in the CMS Convention and in Appendix I of CITES, as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List and the National Wildlife Action Plan (2002-2016). It has also been identified as one of the species for the recovery programme under the Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India.

2022: only four females survive in Gujarat

Himanshu Kaushik, July 13, 2022: The Times of India

Ahmedabad:The Great Indian Bustard (GIB) is one of the heaviest birds that can fly and with only four females surviving in Gujarat, the state forest department is reconciled to their flight into oblivion.

At a meeting held in Gandhinagar recently, senior forest department officers said conservation of the GIB is not feasible in the current circumstances. The four GIBs take long and confident strides in the Kutch region today, unaware that they may be the last of their species in the state not long from now.

The Gujarat government has run out of patience in dealing with the difficulties confronting GIB conservation. In its latest affidavit submitted to the Supreme Court, in April 2022, Gujarat’s energy department suggested that the four GIBs be translocated, so that hightension power lines can be installed and renewable energy infrastructure can be set up across Kutch.

Lala-Parjan Sanctuary in Kutch where the GIBs live is spread over just 2 sq km and is the smallest animal reserve in the country. In the early 2000s, the sanctuary had around 58 GIBs. The last male member of the flock in the sanctuary has been missing since December 2018.

According to a 2018 count, India has fewer than 150 GIBs, of which 122 are in Rajasthan.

Population

2014: less than 200

Great Indian Bustard flying into extinction

Saswati Mukherjee The Times of India Nov 17 2014 Bengaluru:

From: Saswati Mukherjee The Times of India Nov 17 2014

RAMPANT POACHING & HABITAT LOSS MAKE BIRDS VANISH FROM COUNTRY

Less Than 200 Left, Figure In Endangered List

The majestic Great Indian Bustards (GIBs) are vanishing from sight and their dwindling numbers have put them in the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) critically endangered category (red list). According to estimates, less than 200 GIBs are left in the country now.

A huge bird with a horizontal body and long, bare legs, the GIB looks like an ostrich. Among the heaviest of flying birds, they were once endemic to the dry plains of India, abundantly found in the Ranebennur region of central Karnataka. Their population has dwindled significantly because of habitat loss and rampant poaching.

“GIBs are shrinking by the day; their count has fallen below the 200 mark,” says Mohammed Esmail Dilawar, president and founder, Nature Forever Society, Maharashtra.

S Subramanya, scientist and senior faculty member at University of Agricultural Sciences (UAS), says: “Grasslands in the state are being converted to agriculturally fit land and pressure from real-estate development is immense too. Habitat loss is the obvious consequence.” Experts say a vibrant GIB population is reflective of a healthy ecosystem. The bird’s shrinking numbers signal an impending environmental disaster, they warn. “GIBs are an indicator of a healthy grassland ecosystem,” says Sujit Narwade, project scientist, Bombay Natural History Society. “Grasslands as a forest category support biodiversity dependent on it, ranging from termites and spiders to insects and wolves. Unfortunately, they are usually considered wastelands. Many species exist in the food web and food chain in grassland ecosystems. If one is allowed to vanish, other species too will unknowingly disappear.” Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have an estimated population of 10-15 birds each; they can still be spotted in the existing bustard ranges. Gujarat and Rajasthan support a higher number of bustards.

In 2012, the drastic fall in the population of Indian bustards, their endangered status and the decline of grasslands prompted the ministry of environment and forests to draft a species recovery programme for them. Each bustard range state developed site-specific conservation plans, but their implementation has floundered, including of the one in Karnataka.

2019/ 50 left in the wild

From: Mohammed Iqbal, Only 50 Great Indian Bustards left in the wild, no action on plan to save them, January 18, 2019: The Hindu

Almost two years after the Rajasthan government proposed setting up of captive breeding centres for the Great Indian Bustards to boost their wild population, the wildlife activists here have called for enforcement of recovery plan for the country’s most critically endangered bird. The GIB’s last remnant wild population of about 50 in Jaisalmer district accounts for 95% of its total world population.

No progress has been made on the proposal for establishing a captive breeding centre at Sorsan in Kota district and a hatchery in Jaisalmer’s Mokhala village for conservation of the State bird of Rajasthan. The previous BJP regime had taken up the work in 2017 after the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change sanctioned ₹33.85 crore to facilitate the two centres and authorised the Wildlife Institute of India to be its scientific arm.

A group of wildlife activists, who met Rajasthan Minister of State for Environment & Forest Sukh Ram Bishnoi, offered to formulate an emergency action plan for conservation of GIB in order to help the State government tackle the issue methodically.

Tourism & Wildlife Society of Indian honorary secretary Harsh Vardhan, who was among those who met Mr. Bishnoi, said the decisions after the launch of the Project Bustard in 2013 had not been followed up for five years. “The forest officers have concentrated solely on tiger, which has done well. The tiger population is settling outside the Ranthambhore reserve... Two females recently gave litters in scrub areas dominated by human settlements,” he said.

Other members of the group were Sariska Foundation secretary Dinesh Durrani and former Chief Wildlife Warden R.N. Mehrotra.

The group pointed out that the WII had not nominated any scientist to work exclusively on GIB in the State despite the related issues discussed at a meeting held here in April 2017 to decide for setting up the conservation breeding centres. “No progress has been made on land allotment or deputing a scientists abroad to get the breeding training,” the members told the Minister.

Incubation unit

Mr. Vardhan said the group had suggested to the Minister that an incubation unit be set up at Jaisalmer district’s Sudasri — considered the sanctum sanctorum of the Desert National Park — so as to step up recruitment rate of the critically endangered species. “This can be done within a few weeks, whereas the breeding centres will take time,” he said.

Mr. Bishnoi told the group that he would visit the DNP after the ongoing session of the State Assembly was over and convene a meeting of WII, forest officers and wildlife activists to take the GIB programme forward. He agreed that the endangered bird should get the highest priority in the conservation plans.

2019/ 150 left; efforts to save them

Maulik Pathak, Himanshu Kaushik, June 7, 2019: The Times of India

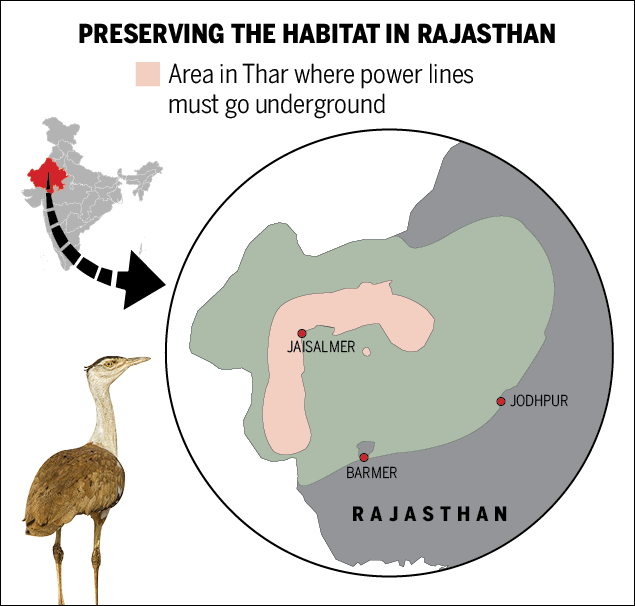

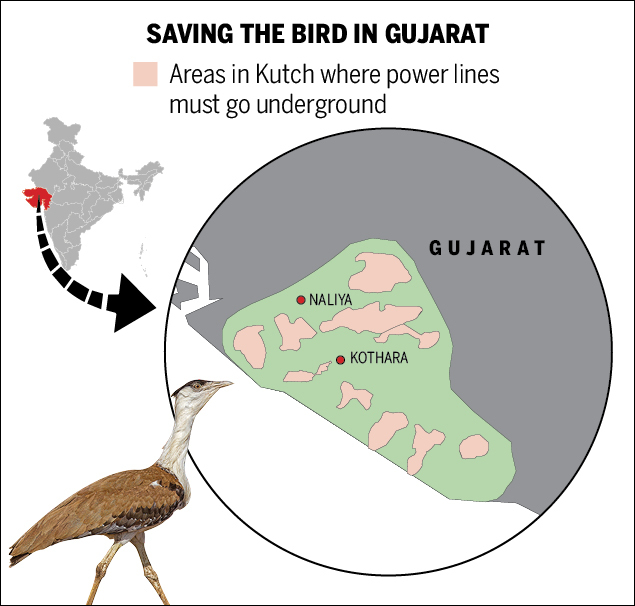

Maps: Wildlife Institute of India

Pictures: Devesh K Gadhavi, deputy director, The Corbett Foundation (Kutch division)

From: Maulik Pathak, Himanshu Kaushik, June 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Maulik Pathak, Himanshu Kaushik, June 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Maulik Pathak, Himanshu Kaushik, June 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Maulik Pathak, Himanshu Kaushik, June 7, 2019: The Times of India

Just 150 left in the wild, fight to save Great Indian Bustard is down to the wire

AHMEDABAD: Researchers this month sounded alarm over koalas in Australia becoming "functionally extinct". Closer home, a critically endangered bird that lost out to the peacock to become India’s national bird may be next in line. There are now less than 150 Great Indian Bustards (GIBs) in the wild -- a rapid decline from 2011 when their population was estimated at around 250.

Even as numbers of the iconic bird continue to slide, lack of cooperation between states and lackadaisical attitude of officials has hit conservation efforts hard. Experts say that the Centre’s push to save the species came only after the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) categorised GIB as “critically endangered” in July 2013. For the heaviest flying bird in the country, it was already too late. Experts have also said little has been done to protect grasslands, the natural habitat of GIB, or address the threats that power transmission lines and windmills pose to them -- strangely a big killer of the birds.

A major factor contributing to dwindling numbers is collision with power transmission lines and windmills. Bustards generally favour flat open landscapes with minimal visual obstruction and therefore adapt well in grasslands. A large number of GIBs have died in the past few years after crashing against windmills or getting electrocuted by low hanging power transmission lines. According to estimates by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), four birds had died in Thar in 2018 alone after colliding with power lines and wind turbines.

Taking note of the threats to the bird, in February this year the ministry of new and renewable energy asked power transmission line agencies and wind energy farm developers to identify areas passing through GIB habitats and take up risk mitigation measures with respective state governments to avoid bird hits. Action suggested included painting tips of wind turbines to make them more visible to the birds in the dark.

H S Singh, member of the Standing Committee of National Board for Wildlife, said there has been a lot of talk about identifying critical areas for retrofitting of transmission lines, yet little has been done.

Forest department officials in Rajasthan and Gujarat, however, said they have identified areas where power lines have to go underground. Experts maintain that this needs to be done on priority basis.

Devesh Gadhvi, deputy director of The Corbett Foundation that works for GIB conservation, added, “State governments should take power lines underground. Since 2014, when the first case of GIB collision in Kutch was recorded, there has been talk about that, but so far nothing has been done. If the bird goes extinct, it will only be due to lack of a political will.”

A Gujarat power official on condition of anonymity told TOI that high costs involved in the project have also been a deterrent. Laying a kilometre of power line underground will cost approximately Rs 1 crore, he said.

In Rajasthan, where GIB enjoys the status of state bird, a plan for ex-situ conservation (captive breeding) has taken several years to materialise.

“Land has been allocated at Ramdevra near Jaisalmer. Houbara Bustard Breeding Centre at Saih Al Salam in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, which has successfully reared as many as 30,000 chicks of houbara bustards has been roped in,” said Sutirtha Dutta, faculty at WII and co-supervisor of the Bustard Conservation Project. Dutta said an MoU has been signed by the WII, Rajasthan government and Dubai for this purpose.

After Gujarat's last remaining male bustard flew away, the state is also mulling a captive breeding centre, according to A K Saxena, principal chief conservator of forests (wildlife). Notably, a breeding centre in Gujarat had been approved by the central government in 2015.

“Gujarat did not have enough bustard eggs to start the centre. There was a proposal to source them from Rajasthan but the project was shelved,” said former principal chief conservator of forests C N Pandey.

The GIB was once distributed throughout Western India, spanning 11 states, as well as parts of Pakistan. Its stronghold was the Thar desert in the north-west and the Deccan Plateau of the peninsula. Today, its population is confined mostly to Rajasthan and Gujarat. Rajasthan has the largest population of GIBs at 120 while Gujarat has six left after its last sub-adult male flew away earlier this year. The grassland habitat in these two states where the bird thrives has long been viewed as wasteland and exploited for agriculture, industry and irrigation projects. Unlike its neighbour China, which has rolled out grassland conservation and management policies that restrict the use of grasslands in some parts, India lacks such a law.

B

DEVELOPMENTS

Artificial breeding

2025

Vimal Bhatia, TNN, April 20, 2025: The Times of India

Jaisalmer : India became the world’s first country to achieve success in the artificial breeding of Great Indian Bustard (GIB) with the birth of the third GIB chick through artificial insemination at Jaisalmer’s Desert National Park.

The technology and training for artificial insemination, obtained from Abu Dhabi-based organisation “International Fund for Houbara Conservation”, contributed to saving this rapidly vanishing Schedule I wildlife species. Wildlife Institute of India (WII) scientists had received specialised training from the organisation.

Suthirto Dutta, WII senior scientist and coordinator of the GIB project at the Jaisalmer Bustard Breeding Centre, said this was the third chick born entirely through artificial methods under this project, marking a historic achievement for India. This groundbreaking development was not just a success of a biological exper- iment but a milestone in giving new life to this rare bird on the brink of extinction.

Dutta said the Bustard Recovery Programme achieved this remarkable feat through artificial insemination. The scientific team procured semen from a male at the Sam Conservation Breeding Centre and artificially inseminated a four-year-old female at the fa- cility. “Project Great Indian Bustard reached a new milestone as the 11th chick of 2025 hatched on April 17 from an egg laid by the female ‘Sharky’ on March 26 in Sam Centre, after being artificially inseminated on March 20 with semen from the male ‘Suda’ housed in Ramdevra Centre, taking the GIB tally in the national conservation breeding programme to 55. This also marked the third success in artificial insemination for the species,” said Dutta.

Dutta said the procedure involved collecting male bustard sperm for insemination, culminating in the birth of a vigorous chick. WII’s endeavours proved fruitful, with the artificial breeding centre demonstrating its efficacy. Specialists verified the chick’s robust health condition. Previously, eggs collected from natural habitats were incubated artificially at the Sudasari Godawan Breeding Centre.

Recovery/ conservation measures

As in 2024

Nikhil Ghanekar, July 3, 2024: The Indian Express

The proposal for the next phase, prepared by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), an autonomous body under the Union Environment Ministry, includes key targets such as rewilding Bustards bred in ex-situ conservation centres, conducting detailed population studies in Rajasthan and other Bustard range states and developing artificial insemination techniques.

The Bustard and Lesser Florican are both critically endangered species. Only 140 Bustards and less than 1,000 Lesser Floricans survive. Over 120 Bustards are found in the desert and semi-arid landscape of Rajasthan alone; the rest survive in the wild in other range states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh while Madhya Pradesh, another range state, has not recorded a Bustard sighting for several years.

Here’s a look at what is the Bustard conservation program, what has been achieved so far and what needs to be done to secure their habitats

What is the Great Indian Bustard recovery plan and conservation program?

The Great Indian Bustard is a large bird found only in India. It is known to be a key indicator species of the grassland habitat, which means its survival also signals the health of grassland habitats.

Over the past four decades, its population has declined steadily from being in the range of 700 individuals to less than 150 as of today, as per the Rajasthan Forest Department. Loss of their habitat to rising farmlands in semi-arid regions of Rajasthan, depredation of eggs by other predators such as dogs, monitor lizards and humans and more recently, death due to overhead power lines have caused their numbers to decline.

In fact, the threat from power lines was the subject matter of a recent plea before the Supreme Court which resulted in an important order. The Supreme Court, while agreeing with the government’s contention that overhead power lines could not be entirely eliminated from the bustard’s habitats, had constituted an expert committee to determine the “scope, feasibility and extent” of overhead and underground electric lines in the area.

The poor frontal vision of the GIB’s and their inability to swerve away from overhead power lines in their flying path, owing to their large size, are two key factors leading to their collision with transmission lines. A 2020 WII study estimated that 18 GIB’s die annually due to collision with overhead high-tension power lines in the Thar landscape. Such a high mortality rate can wipe away the bird’s wild population, the WII had noted.

The committee was also asked for other measures for better conservation of the bird. While examining this case, the Supreme Court also recognised the right of the people against adverse impacts of climate change as part of the fundamental right to life and right to equality.

The first steps to address the decline of the bustard population were taken between 2012-2013, when the Rajasthan government as well as the Environment Ministry began a long-term Bustard and Lesser Florican recovery project. The recovery project firmed up more in the year 2016 when it received a funding outlay of Rs 33.85 crore for seven years. This money was sanctioned to improve the bird’s habitat and start a conservation breeding program.

The Compensatory Afforestation Fund, which consists of money collected for afforestation in lieu of diversion of forests for non-forest uses, funded this project. Later, in July 2018, a tripartite agreement was signed between the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Rajasthan Forest Department and Wildlife Institute of India (WII).

This involved opening long-term conservation breeding centres (CBC) in Ramdevra and Sorsan, implementing field research projects such as telemetry-based bird tracking and population surveys, habitat management as well as outreach to local communities.

What has been achieved so far at the breeding centres?

Before the development of the CBC in Ramdevra, work on the conservation breeding in June 2019 at the temporary facility in Sam, Jaisalmer. conservation breeding began by collecting eggs from the wild. The eggs are incubated artificially at the centres and hand-reared in the breeding centre itself. Later, chicks that attained adulthood at the centre have mated and given birth to the next generation.

The breeding centres now have a founder population of 40 GIBs, of which 29 were those whose eggs were collected from the wild. The remaining 11 were born to those who were mated at the centre.

The scientific reasoning behind creating a founder population is to have a minimum viable population to prevent the probability of extirpation of the captive population and to capture the genetic variability of the source population. A minimum of 20 adult birds including 15 females is needed to establish a minimum viable population in captivity, as per the 2018 tripartite agreement.

The WII team plans to continue collecting four to six eggs per year until the captive-bred birds are released in the wild. For Lesser Floricans, since their population is still around 1,000, only two or four eggs will be collected from the wild.

What’s planned ahead?

While the total length of the next phase of the GIB and Lesser Florican conservation is 2024-2033, the immediate next phase will run till 2029. The target of the project would be to complete the upgradation of the CBC at Ramdevra and development of the Lesser Florican CBC at Sorsan, both in Rajasthan. The Ramdevra facility would also include a new lab for artificial insemination, which the WII plans to use from 2026 onwards.

Conducting population surveys in Jaisalmer, other parts of Rajasthan and the range states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh will be done in the next two years. The most important target in the next five years would be releasing the captive-bred GIBs in the wild. The actual release in the wild would be preceded by soft release in enclosures in Rajasthan. The captive-bred GIBs would also be trained for release in these enclosures, as per WII scientists.

What has been done for habitat management and are they secure for rewilding of captive Bustards?

Bustards today face major threats to their survival. Any chance that the large birds have to survive in the wild depends on mitigating the risks posed by these threats. Delhi-based wildlife biologist Sumit Dookia, who runs a community conservation project on Bustards in Jaisalmer, said that the district’s landscape has undergone a lot of habitat changes in the last 20 years.

Most of the wild Bustards are using habitats that are outside the forest department’s jurisdiction in farm fields. “The current wild habitat is not at all secure and safe for GIB, even with the Supreme court’s order to place good quality bird diverters (to prevent collisions). In the last five-six years, 10 GIBs have been found dead under power lines in Jaisalmer alone,” Dookia said.

Kedar Gore, Director, The Corbett Foundation and Member, the International Union for Conservation of Nature Species Specialist Commission (Bustard Specialist Group) sought to draw attention to a tripartite agreement clause. It says that Bustard release sites must cumulatively have 200 sq km of inviolate space within the GIB landscape and comprise secured habitat patches exceeding 20 sq km each while the connecting habitats in between should not have hostile infrastructure.

“Power lines are a proven threat for bustards and considering the speed of ex-situ work, it is imperative to speed up mitigation of power lines and prepare such areas in Rajasthan and range states like Gujarat and Maharashtra. Habitat restoration should also happen with the support and benefit of the local community, keeping their livestock grazing rights under consideration,” Gore said.

On its part, WII has mapped the threats posed by power lines and renewable infrastructure across the 20,000 sq km GIB landscape. In collaboration with Humane Society International, 801 dogs were sterilized in 23 villages in and around the Desert National Park in 2018-19 while GIB predators such as monitor lizards, foxes and dogs were also captured and translocated from Bustard breeding areas, as per WII’s annual report on the recovery program.

Threats

Hunting

The biggest threat to this species is hunting, which is still prevalent in Pakistan. This is followed by occasional poaching outside Protected Areas, collisions with high tension electric wires, fast moving vehicles and free-ranging dogs in villages. Other threats include habitat loss and alteration as a result of widespread agricultural expansion and mechanized farming, infrastructural development such as irrigation, roads, electric poles, as well as mining and industrialization.

See also

Great Indian Bustard