Grand Trunk (GT) Road

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

GT Road cuisine

April 9, 2006

The road oft taken

This book is about the emergence of the Grand Trunk Road as a major route for traders and invaders headed to India, and the culinary riches that it offers to travelers

Pushpesh Pant and Huma Mohsin write about the fascinating origins of the Grand Trunk Road and the various social roles it has assumed over the centuries

The Grand Trunk Road or the GT Road as it is popularly known is best visualised as a mighty river meandering its way over a 2,500km course transporting on its surface millions of passengers and a mind-boggling amount of cargo everyday. The GT Road serves as a life-sustaining link that has acquired over centuries, since it was first built, an iconic status. It has spawned halting stations/resting places that have evolved into towns full of colour and character, each distinct from the other.

It is a symbol of the subcontinent’s unity in diversity or the other way round. Politics may have partitioned India and Pakistan but the GT Road rolls on across the man-made border majestically. Like any great waterway, this road also has many tributaries and distributaries. It would not be an exaggeration to claim that more than half of the subcontinent’s population has had its life touched by the GT Road one way or the other.

It was the great balladeer of the Raj, Rudyard Kipling, who had first brought alive the romance of this road for the western audience. In his famous novel, Kim, he went into raptures describing it ...

Although almost everyone vaguely remembers Sher Shah Suri in the context of the Grand Trunk Road and some even connect Emperor Asoka with the trail, very few recall that it was the Mughal Emperor Jahangir who planted the trees that grace the Grand Trunk Road and were noticed by the early European travellers.

Jahangir has noted in his memoirs:

“According to orders they (the officials) planted trees on both sides (of the road) from Agra as far as the river of Atak (the Indus) and had made an avenue in the same way from Agra to Bengal.”

Thomas Coryote walked his way from Spain to India in 1615 and the journey from Aleppo to Ajmer took him 10 months. The entire expenses were limited to 15 shillings. He was known to Indians as the English Fakir. From Lahore to Agra, he travelled on the GT Road and was deeply impressed by its quality.

When the power of the Mughals diminished and disintegration of the empire set in, in the middle of the 18th century, the delta of the rivers Ganga and Yamuna was repeatedly ravaged by warring armies. The tree-lined avenue was denuded of all its glory. The embanked road suffered neglect and became a veritable nightmare during the monsoon. This sad state of affairs had resulted from raging anarchy ...

Asoka the Great, we know through his edicts, had ordered that rest houses be built at every eight kilometres. Almost a thousand years after him, Harshvardhan of Kanauj had also commissioned the construction of charitable dharamshalas to ensure that wayfarers never find themselves in dire straits. It was Asoka who, according to legend, and lore first dreamt of connecting Purushpur (Peshawar) the westernmost frontier outpost in his empire with the imperial capital Patliputra by a strategic highway. Asoka, when a young prince, had served along this border and memory was still green in his mind of the Greek invasion led by Alexander the Great during the reign of his own grandfather, Chandragupta Maurya.

Interestingly, Asoka, though credited with the vision of this pan-Indian highway, may himself have only extended and improved upon a historic route well-trodden before his own birth. In the Hindu epics and Puranas, there are references to two major arterial roads — Uttarapath and Dakshinapath. Each road cut a swathe in north and south respectively to facilitate trade and commerce and movement of troops. It is not far-fetched to suggest that the origins of the Grand Trunk Road lie in the intrepid explorations of the Aryans as they spread out west to the east beyond the Indus and the land of the five rivers, clearing forests founding agricultural settlements.

The GT Road is the backbone that gives physical shape and psychological colour to the racial memories of the majority of Indian people. On one extremity, the GT Road almost touches the sweep of the exotic silk route and on the other, it is within striking distance of the ports that open the passage to the aromatic spice route. It is difficult to imagine how many pilgrim circuits have effortlessly been subconsciously interwoven. For a majority, the father of GT Road is Sher Shah Suri, the Afghan soldier, who in his meteoric career had ousted Humayun, the son of Babur (founder of the Mughal dynasty, 1483-1530), from the throne of Delhi. During his short reign (1540-1555), he initiated wide-ranging administrative reforms, land settlements and ambitious building projects.

The groundwork, it is true, had been undertaken by his Mauryan predecessor in the fourth century BC, but it was Sher Shah who revived and gave a new lease of life to the Grand Trunk Road. Born in Sasaram, Bihar, he too shred Asoka’s dream of connecting the seat of his

Politics may have partitioned India and Pakistan but the GT Road rolls on across the man-made border majestically. Like any great waterway, this road also has many tributaries and distributaries

principality with the land of his ancestors. Trees were planted along the road, caravans and sarais constructed and patrolling of the route ordered to stop brigandage ...

Many of these sarais were remarkably beautiful and had a distinct personality of their own. The sarai at the entrance to Agra had vaulted rooms and impressive domes. It could accommodate almost 3,000 guests and provide a stable space for 500 horses. The sarai south of Jallandhar, built by Jahangir, was square in shape with each side measuring 165m, its four corners were decorated with octagonal towers. In 1638, it is recorded that there were 80 caravan sarais for foreign merchants in Agra. The ruins of these sarais can be found in Jallandhar, Agra, and Mathura. The stretch of the road between Agra and Lahore was best maintained and experienced travellers could cover 40km in a day.

Sher Shah died suddenly in an accident while watching a display of pyro-technics and this allowed Humayun to make a come back and reclaim his Mughal legacy. As Humayun’s son, Akbar, continued with many of Sher Shah Suri’s projects, the Grand Trunk Road grew in significance. Its existence ensured that the emperor could swiftly dispatch punitive expeditions to discipline delinquent and ambitious provincial governors or quell revolts and rebellions effectively. The road could not be allowed to fall into disrepair. It not only connected the imperial cities — Delhi and Agra — but also linked these with the historical pilgrimages of Allahabad and Varanasi for Hindus and fonts of culture.

Things changed when Aurangzeb incarcerated his father Shah Jahan, the builder of Taj Mahal, Jama Masjid and the Red Fort, and imposed an austere code on his courtiers. Much of his time was spent in the Deccan campaigns and the Uttarapath, taken for granted, was neglected. The GT Road suffered and fell into disrepair. The jungle began to encroach on the pathway. By the time Aurangzeb died only the shell remained of the once mighty Mughal empire. Invaders like Nadir Shah sacked Delhi, indulged in carnage and dealt a fatal blow to the Mughal empire.

Disintegration followed soon and by the middle of the 19th century disturbed circumstances made travel along the Grand Trunk Road quite hazardous.

Ghalib, the famous Urdu poet, has chronicled his passage from Delhi to Rampur, providing interesting glimpses of such a journey. One rode on horseback or was carried more comfortably in a palanquin guarded by a detachment of armed soldiers and had to make arrangements for food and drink along the way. The journey had to be well-planned to reach a comfortable camping site before dark. Even beyond Rampur things were not much better. This is where the notorious Pindaris, the ruthless thugs who had been driven away by the legendary Colonel Sleeman from the wild forests of central India, roamed. The accounts of Christian missionaries like Bishop Heber and J. Kennedy, protected by colonial troops, reinforce the descriptions of Ghalib.

People understandably preferred to travel along the more secure waterways especially between Allahabad and Varanasi, Varanasi and Patna, and Patna and Kolkata. Towards the end of the 19th century, the multifaceted genius and bon vivant, Bhartendu Harish Chandra and the great Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, undertook a number of such river journeys and their travelogues show us how land travel had decayed. The painters of the Raj, the Daniel brothers (William and Thomas) and Edward Lear too have left wonderful sketches, aquatints, and paintings documenting this change.

The fortunes of the Grand Trunk Road changed when the British took control. They wished to eliminate, for strategic reasons, all possible delays that could slow down an army on the march. Their priority was to establish a direct line of communication and transport from Fort William at Kolkata to the farthest frontier outpost. The famous surveys were undertaken with this purpose in mind. Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of India, persuaded his council of building a road from Kolkata to Chunar to be named the New Military Road. The idea was abandoned after almost 50 years when work began on an even more direct road through Burdwan. This road was completed in 1838.

There are divergent accounts, travelogues and literary sources that make it difficult for us to plot with any degree of accuracy the course of the Grand Trunk Road in the ancient period. According to the Buddhist texts, there was a road, well travelled, that followed the foothills of Punjab and continued towards Mathura along the Yamuna river. When Mohammad Ghori invaded India in the 11th century AD, he traversed the course a little further south than the present Grand Trunk Road between Lahore and Panipat.

The road shifted again due to imperial decisions in the middle of the 16th century. Sher Shah Suri built a fort at Rohtas on the Jhelum and Akbar at Attock on the Indus. Travellers were obliged to cross the river specifically at these points. In this part the road followed the alignment of the present-day highway. Originally it seemed that it did not pass through Amritsar.

When the British control was extended to the region of Punjab and Lord Bentinck became the governor-general of India, the British were quick to recognise that the significance of the great road that had fallen into disrepair and disuse. The road was metalled in 1856. Many of the repairs and improvements were under the supervision of James Thomson, the lieutenant-governor of the north-west provinces, who has been described by Phillip Mason as “the father of public works, in particular the Grand Trunk Road, the Ganges canal and the Engineering Colleges at Roorkie ...”

Obscure, forgotten settlements in the backwaters in the hinterland — Phagwara, Ludhiana and Jallandhar — were almost overnight turned into pulsating places full of potential and promise. The construction of a complex network of canals transformed agriculture in the province but it was the road — the one and only GT Road — that made it possible for Punjabis to benefit from this change. What transformed the GT Road was the advent of motorised transport and the decline of inland waterways.

What revived interest in the GT Road was the Mutiny of 1857 and establishment of British empire removing the veil of the Company rule. Strategy and colonial commerce took precedence over all else and overriding priority was accorded to keeping channels of communication and transport open. The Grand Trunk Road was repaired, broadened, and rendered safe for the common traveller. By the time motorised automobiles made their appearance, the Indian autobahn was ready to receive them.

And it is not only the Punjabis who benefited. The GT Road connected Lahore — the Paris of the Orient — with the rest of the land. In the years before independence and particularly during the inter-war period, the GT Road brought Bengalis, Marathis, Gujratis and Madrasis to Lahore and Amritsar and contributed significantly in the evolution of a composite culture.

When partition came, the Grand Trunk Road bore the painful burden of the traffic of refugees — the helpless victims of unprecedented communal bloodshed, loot, rape and arson. Millions moved in both directions — this perhaps is the saddest chapter in the long history of the road. The influx of the homeless — countless separated families had an unexpected outcome.

The community kitchen, sanjah chulha, centering round the clay oven (tandoor) became the essential life-support system of the immigrants. With the passage of time the tandoori style of cooking would radiate like spokes from a hub and engulf the entire nation in its warm glow. A hole in the wall outlets in earthen huts with thatched roofs began to mushroom along the Grand Trunk Road — the ubiquitous dhabas. It was not long before the dhaba became synonymous with “great value for money, just like mom’s home-cooked, lip smacking, nourishing fare.”

However, one should not be in a hurry to conclude that all one can eat along this journey is robust, rustic but tasty Punjabi fare. As a matter of fact, driving along the GT Road one has an unmatched opportunity of discovering the culinary riches of India. With the exception of the coastal and the peninsular, one can encounter and savour all the flavours, seductive and addictive ranging from the barbequed temptations of Peshawar and Pindi to piece de resistance of the imperial dastarkhans of Delhi and Agra to the delicacies of the Awadh region to subtly sublime vegetarian repast of Varanasi to the tantalising gastronomic gems of Bengal. The GT Road is the best introduction and irresistible invitation to “taste India.”

Excerpted with permission from: Food Path: Cuisine Along the Grand Trunk Road From Kabul to Kolkata By Pushpesh Pant and Huma Mohsin Roli Books. Available with Liberty Books, Park Towers, Clifton, Karachi. Tel: 021-5832525 (Ext: 111). Website: www.libertybooks.com ISBN 81-7436-362-9 141pp. Rs895

Pushpesh Pant is a professor of diplomacy at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi and is a well-known authority on culinary matters

Huma Mohsin is a cookery expert and lives in Peshawar May 14, 2006

REVIEWS: It goes on forever

Reviewed by Asif Noorani

Going through the contents of Food Path — the colourful photographs, the history and geography of the highway that stretches from Kabul to Kolkata, the description of delicious cuisine that punctuate the long route and their recipes — one wonders where to place the book — on the bookshelf in the study, centre table in the drawing room or in the kitchen? It’s an amazing publication and its central character is, of course, the Grand Trunk Road (Jarnaili Sadak in Urdu and Hindi). The GT Road, as it is commonly known on both sides of the Great Divide, may not have the mystique of the Silk Route, but it certainly has no less to offer: culinary diversity being only one of the many.

Said Rudyard Kipling, “It is to me as a river from which I am withdrawn like a log after flood. And truly the Grand Trunk Road is a wonderful spectacle. It runs straight, bearing without crowding Indian traffic for 1,500 miles such a river of life as no where else exists in the world.” It may not be a river but the GT Road certainly crosses almost every major river of the northern part of the subcontinent from the Indus to the Ganges, not to speak of two international borders, one at Wagah and the other at Torkham. The authors of Food Path rightly claim that more than half of the subcontinent’s population has its life touched by the GT Road, one way or the other.

Going through the history of the highway, one is reminded of Tennyson’s famous lines: “For men may come and men may go / But I go on for ever.” The GT Road was built by Sher Shah Suri, “the great ruler, reformer and innovator”, who “interrupted” the rule of the weakest of all the great Mughals, Humayun for a period of 15 years. The highway was punctuated with resting places located after every eight miles. The fourth Mughal emperor Jehangir went a step ahead, when he got shady trees planted on both sides of the road, throughout its length. A French traveller, Anquetil Duperron, marvelling at the quality and quantity of plantations, wrote in his travelogue, “The tree beneath which I halted cover with its shade more than 600 people.”

The Grand Trunk Road fell upon bad days when the Mughal Empire weakened. Thugs prowled in some sections and armies marched over its dilapidating surface. By the 19th century travelling on the highway became hazardous. The authors refer to Ghalib, who travelled from Delhi to Rampur, with armed guards, and makes a mention of it in his writings. That such security steps were necessary is borne out by the accounts of Christian missionaries who travelled on the GT Road about the same time.

The British gave a new life to the highway when they repaired and improved it, metalling it in 1856, a year before what they call the Mutiny and what the people of the subcontinent term the War of Independence. “Strategy and colonial commerce took precedence over all else and overriding priority was accorded to keeping channels of communication and transport open … By the time motorised automobile made their appearance the Indian autobahn was ready to receive them,” says the Introduction.

The grimmest chapter in the history of the GT Road saw long caravans of refugees — “the helpless victims of unprecedented communal bloodshed, loot rape and arson” — crossed the newly created border, from both sides. And there were millions of these unfortunate and uprooted people.

Food Path claims that dhabas (roadside eateries) emerged when some enterprising refugees from Pakistan, looking for livelihood, set them up. But on our side of the Wagah border this was done largely by the Pakhtoons, who catered to the dietary requirements of the truck drivers who largely hailed from the NWFP. In both cases some of these modest restaurants grew into larger establishments once they attracted families from the nearest cities but this was achieved only on the basis of the quality of food. An interesting parallel can be drawn with the Pakistani restaurants in Manhattan, which were the haunts of cab drivers from this country. Now these joints are frequented by Pakistanis, and even Indian and Bangladeshis, pursuing different professions.

To those into culinary skills, Food Path’s main attraction would be a hundred vegetarian and non-vegetarian recipes, not to speak of the desserts. Each recipe appears on the scene where the dish belongs to. For instance, the chappali kabab recipe is placed on the page relating to Kabul, while rosogolla (rasgulla to us) appears in the penultimate age where the journey ends. Not many of us know that this form of sweet was invented by the Bengalis. The one anomaly is in the case of nihari, which appears on the page pertaining to Lahore and nehari in the context of Kanpur. There is hardly any difference between the two. The fact remains that nihari originated in Delhi and flourished in Karachi after partition. There are very few joints of this dish in Lahore, where paye is the specialty. It is in Karachi that you get nihari in every locality — morning, noon and night. No one but the Karachiwalas have taken the dish to different parts of the world, mainly the UK, the USA and the UAE.

The recipes in the book give the local names of the ingredients too. Strangely enough, lamb is suggested and not mutton (goat’s meat) which is preferred all over the subcontinent, except in the Frontier Province. This change has been probably made for the western readers of the book, who are likely to be interested in the recipes. In the West, lamb meat is popular and mutton hardly known.

Footnotes and boxes on such interesting subjects as Truck Art in Pakistan and the langars (community kitchens) in gurdwaras, particularly the Golden Temple in Amritsar are bound to interest the readers. Incidentally, not many Pakistanis are aware that the foundation stone of the great temple of Sikhs was laid by Mian Mir, a Muslim saint, who lies buried not too far — in Lahore.

The photographic contents of the publication (a good number of them from our side were provided by K.B. Abro) are eye-catching and absorbing. Those into photography are likely to be interested in the publication too. A fine specimen of truck art makes a good cover and on a highway littered with trucks there couldn’t have been a more appropriate image.

Food Path: Cuisine Along the Grand Trunk Road From Kabul to Kolkata

By Pushpesh Pant and Huma Mohsin

Roli Books, Available with Liberty Books,

Park Towers, Clifton, Karachi

Tel: 021-5832525 (Ext: 111)

Website: www.libertybooks.com

ISBN 81-7436-362-9

141pp. Rs895

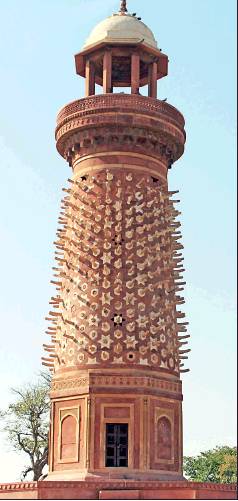

Kos minârs

From: Arvind Chauhan, These were the ‘Google Maps’ of 16th century, now they’re lost in time, March 2, 2019: The Times of India

Hailed as a “marvel of India” by early European travellers, including Sir Thomas Roe, and described as an integral part of the country’s “national communication system” by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), Sher Shah Suri’s kos minars, which once marked the way for thousands, are now themselves lost by the wayside.

The 30-foot-tall medieval milestones built at every kos (an ancient unit of distance equivalent to approx. 3 km) along the Grand Trunk Road in northern Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan today stand isolated, lost among villages, farm fields, slums, near railway tracks and even in zoos. Given protected status by ASI, these minars have down the centuries come to become heavily encroached upon and vandalised.

Abul Fazl records in “Ain-e-Akbari” — a detailed document on the administration under Mughal emperor Akbar — that there were around 600 minars during the Mughal period. Now only 110 remain in UP, Delhi, Haryana, Rajasthan and other places. Taking cognisance of the historical significance of these minars, restoration work on these was initiated last year, says ASI.

Two Englishmen, Richard Steel and John Crowther, who visited Punjab in April 1615 described kos minars in detail. So did Roe, ambassador of King James I at Jahangir’s court in Agra between 1615 and 1618.

Dharam Vir Sharma, former superintendent archaeologist of ASI in Agra, said, “In the third century BC, Mauryan emperor Ashoka initiated ancient routes originating from his capital city Pataliputra that extended up to Dhaka in the east and Kabul via Peshawar in the west and further to Balkh (Bactria, in central Asia). These routes had landmarks in the form of mud pillars, trees or even wells to guide commuters. During Ashokan period, a letter from Pataliputra (modern-day Patna) used to reach Kabul in maximum seven days.

“Later, Sher Shah Suri, and also the Mughals, restored the concept and erected kos minars on three major routes, which were called Sadak-e-Azam (later the Grand Trunk Road).”

Divay Gupta, principal director of Architectural Heritage division of INTACH, a private organisation working for the conservation and preservation of culture and heritage, said, “Urban expansion has destroyed most kos minars. Neither tourists and nor even locals are interested in it as most are not aware of their historical significance. Some of them are protected from encroachment and vandalism, but they have lost their context and stand isolated with little purpose or direction.”

A senior ASI official said, “Fortunately, courts have frequently come to the support of kos minars. Delhi high court recently ordered authorities to clear encroachments around the Mathura Road kos minar in Badarpur. Also, Rajasthan HC issued instructions to authorities to conserve the kos minar situated at Moti Doongri road in Jaipur.”

Ramesh Kumar Singh, assistant superintendent archaeologist of ASI in Agra, said, “Preservation and restoration work for nine kos minars was started in Mathura last year.”

The 30-foot-tall medieval milestones built at every kos (unit of distance equivalent to approx. 3 km) along the Grand Trunk Road in northern Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan are today lost among villages, fields, slums and even in zoos