Glacier bursts: Chamoli

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

2021

The events

February 8, 2021: The Times of India

From: February 8, 2021: The Times of India

In a horrific disaster reminiscent of the Kedarnath tragedy in 2013, a huge glacier burst in the Tapovan area of Uttarkhand's Chamoli district in the Garhwal Himalayas on the morning of February 7, triggering a flood that resulted in massive devastation and loss of lives.

WHAT HAPPENED

A huge chunk of what is suspected to be a glacier in the Nanda Devi landscape broke and fell into the Dhauliganga river, one of several tributaries of the Ganga river, near Raini village in Chamoli district of Uttarakhand.

A swollen Dhauliganga river flowed down to Vishnuprayag, which is where the Dhauliganga and Alaknanda rivers meet. Water level in the tributaries also rose considerably. The force of the river was so much that is washed away the 13.2MW Rishiganga hydropower project near Joshimath and also caused considerable damage to 520MW Tapovan-Vishnugad hydropower project.

The maximum water level at Tapovan barrage is 1,803 metres, but according to reports, the water level crossed 1,808 metres, which led to the breakage. By the time the water reached Joshimath, its level had touched 1,388 metres, breaching all records. During the flash floods in the state in 2013, the highest water level at Joshimath was 1385.54 metres, experts said.

THE LOSS

Around 18-20 bodies had been recovered until Monday morning, but more casualties are expected. About 200 people are still missing. Most of those killed or missing are believed to be workers at hydropower projects. Villagers close to the river when the disaster occurred were also swept away. Several workers are trapped in tunnels at the site of the disaster.

Two hydropower projects in the area were hit. The 13.2MW Rishiganga hydropower project near Joshimath was completely washed away.

The state-run NTPC 520MW Tapovan-Vishnugad hydropower project on Dhauliganga river was also badly damaged. Initial estimates put the cost of the dam and the office that were washed away at Rs 450 crore.

A total of five bridges – one motorable, four suspension – were damaged, cutting access to around 18 villages in the area. Some small private projects have also been hit. About 200MW power supply to the national grid has been cut.

Teams of the State Disaster Relief Force (SDRF), National Disaster Response Force (NDRF), Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) and Indian Army are involved in rescue operations.

Causes

WHAT CAUSED THE DISASTER

A glacial lake outburst flood

Some scientists say the disaster could be because of a “very rare” phenomenon where water pockets within a glacier burst.

This is called a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF). A glacial lake is a body of water with origins from glacier activity. They are formed when a glacier erodes the land, and then melts, filling the depression created by the glacier.

Unlike normal lakes, glacier lakes are unstable because they are often dammed by ice or glacial sediment composed of loose rock and debris.

When accumulating water bursts through these accidental barriers, massive flooding can occur downstream.

A study published in Nature Climate Change says GLOFs often result in catastrophic flooding downstream and have been responsible for thousands of deaths in the last century, as well as the destruction of villages, infrastructure and livestock.

In January 2020, the UN Development Programme estimated that more than 3,000 glacial lakes have formed in the Hindu Kush-Himalayan region, with 33 posing an imminent threat that could impact as many as seven million people.

Signs of climate change

Geologists say increasing global temperatures have accelerated glacial reduction. Himalayan glaciers are retreating faster than anywhere else in the world — this has been most pronounced since the 1990s.

With temperatures in the hills of Utttarkhand’s Chamoli district dropping to below zero in the month of February, why did the glacier break off now? According to Manish Mehta, senior scientist at Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, “This is an anomaly. In winter, glaciers remain firmly frozen. Even walls of glacial lakes are tightly bound. A flood of this sort in this season is usually caused by an avalanche or landslide. Neither seems to be the case here.”

In a study last year, it was found that eight glaciers of the upper Rishiganga catchment — Uttari Nanda Devi, Changbang, Ramni Bank, Bethartoli, Trishul, Dakshni Nanda Devi, Dakshni Rishi Bank and Raunthi Bank — had lost over 10% of their mass in less than three decades, shrinking from 243 sq km in 1980 to 217 sq km in 2017. Uttari Nanda Devi glacier had receded the most at 7.7%. The upper Rishiganga catchment is where the glacier burst took place. In the same period, the equilibrium line altitude (the zone on a glacier where its mass lost is balanced by its mass gained over a year) fluctuated a lot — between 5,200m above sea level and 5,700m. If climate conditions are consistent, it does not change. The equilibrium line altitude swing suggests glaciers in the region have responded to deprived precipitation conditions since 1980.

'Disaster was manmade’ Villagers say the Rishiganga hydropower plant built in the area was in contravention of all environmental norms and had been flagged by villagers as an ‘impending disaster’. A resident had even filed a PIL in the Uttarakhand HC alleging the private firm was “using explosives and blasting the mountains for mining.”

Conservationist and Magsaysay awards winner Rajendra Singh, also known as the ‘waterman of India’ said, “No dams should be constructed on river Alaknanda, Bhagirathi and Mandakini as there are very steep slopes in the area and is an extremely eco-sensitive zone. However, rampant construction continues due to which the disaster was inevitable. This was a manmade disaster.”

Ironically, Raini village where the disaster struck is the cradle of the Chipko Movement, initiated by villagers in Uttarakhand in the 1970s to save trees.

Massive rockslide triggered flood

Vishwa Mohan, March 6, 2021: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, March 6, 2021: The Times of India

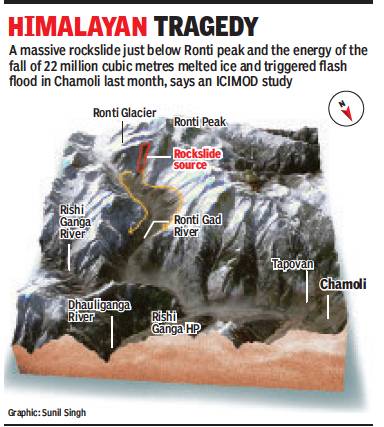

A massive flash flood in Chamoli district of Uttarakhand that ravaged through the valleys of Rishi Ganga, Dhauliganga and Alaknanda rivers last month was triggered by a massive rockslide just below Ronti peak and the energy of the fall melted the ice creating the source of flood, said findings of an intergovernmental body, International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

The findings said the energy of the fall of 22 million cubic metres of rock mixed with ice and snow “remobilised the debris and ice on the valley floor deposited by previous events, pushed the stream water and created an excessive flood wave”.

The ICIMOD researchers found that the rockslide had an approximate width of 550 metres at the upper edge at 5,500 metres above sea level.

Noting that the event was definitely not caused by a ‘glacial lake outburst flood’ as there were no significant glacial lakes in the area, the report said a couple of days prior to the February 7 event, a strong western disturbance resulted in heavy precipitation, which increased the flood magnitude.

The Kathmandu-based ICIMOD has eight member countries, including India, on board which is considered as the most authoritative voice in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region.

Water in glacier the main reason

Kautilya Singh & Mohammad Anab, February 15, 2021: The Times of India

Geologist Naresh Rana of Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal University, who was among the first experts to notice the new lake formation at the site of the floods, told TOI that while an avalanche may have acted as a trigger, water accumulated inside the glacier was the “real culprit”.

“Glaciers often have accumulated water inside their crevasses or in small sub-glacial lakes. In this case, the water must have reached its saturation point. Any avalanche or landslide may disturb the glacier’s process and break its reservoir, leading to a sudden increase in water outflow. Then it flows along with heavy sediments at a rapid speed along a steep slope.” He added that “had it been just an avalanche, it would have stayed confined to the valley.” “It was the accumulated water inside the glacier, punctured by an avalanche, that caused the river to swell, leading to flash floods.”

Meanwhile, scientists of Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology said a chunk of hanging glacier, around 500m in length, had broken off and fallen into the Raunthi river, causing ‘an explosion like sound.’ This was at 2:30am. Over the next eight hours, a slurry of ice, water and boulders ended up in Rishiganga, triggering the flash flood.

Massive rock and ice avalanche

Chandrima Banerjee, June 11, 2021: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, June 11, 2021: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, June 11, 2021: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, June 11, 2021: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, June 11, 2021: The Times of India

After months of debate over what led to the Uttarakhand floods in February this year — glacial lake outburst or rockslide — a team of 53 scientists from across the world has confirmed “an extraordinary rock and ice avalanche and debris flow” was the cause, using a computer model to reconstruct “in almost real time” how the flood unfolded. But only a part of the rock-ice mass collapsed from Ronti Peak in February, scientists warned, leaving a substantial chunk vulnerable.

The findings, by scientists from the universities of Calgary, Colorado, Washington, Zurich, Potsdam, Utah, Toulouse, Heidelberg, Geneva, Newcastle, Oslo and Utrecht, among several others, were published in the ‘Science’ journal. “There is no ambiguity that the event was a rock/ice avalanche,” co-author Dr Irfan Rashid from the University of Kashmir told TOI.

And it could happen again. “High-resolution Google Earth data over the Ronti Peak suggests that only a bigger hanging glacier collapsed in February. There is still a substantial chunk of highly crevassed ice that could be vulnerable,” said Rashid.

Lead author Dr Dan Shugar, from the University of Calgary, added, “If one is only looking for dangerous glacial lakes, they will miss the dangerous slopes that could produce the very mobile and destructive debris flow, such as we saw.” The paper further said, “Chamoli event may be seen in the context of a change in geomorphological sensitivity and might therefore be seen as a precursor for an increase in such events as climate warming proceeds.”

As to why glacial lake outburst was ruled out as a cause, Shugar said, “For GLOFs, there would typically be pretty obvious signs or scouring and erosion downstream of the outburst site. But at Nanda Devi and Nanda Ghunti glaciers (where it was suggested the glacial lake originated), no evidence was observed of any changes whatsoever in the days prior to February 7 (when the floods surged through Rishiganga and Dhauliganga rivers). There were also no visible lakes in the days prior.”

What they found while recreating — with satellite imagery, seismic records, digital models of the terrain and videos — what happened on February 7 was a series of “extraordinary” events.

Seismic data from two stations, 160km and 174km from the source, indicated that around 10.21am, a 20 million m3-mass of rock (80%) and ice (20%) broke off an altitude of 5,500m above sea level and hit the Ronti Gad (rivulet) valley floor about 1,800m below. The average speed of the avalanche was 205-216 kmph down the 35° mountain face. “The incredible frictional heat generated during the disintegration of the rock mass melted nearly off the ice during descent. The liquid water is what allowed the debris to become so mobile,” Shugar said. “Typical rock avalanches that don’t contain a lot of glacier ice or water tend to flow a long distance, maybe only a few kilometres, not the tens of kilometres we saw here. This was a different sort of event.”

Then, the fall itself was exceptional. “The ~3700 m vertical drop to the Tapovan HPP is surpassed clearly by only two known events in the historic record, namely the 1962 and 1970 Huascaran avalanches,” the paper said, referring to a 1962 avalanche on the slopes of an extinct volcano and a 1970 debris avalanche triggered by an earthquake in Peru. “The ratio of rock to ice, and the extreme fall height produced a ‘worst case’ scenario, where there was just enough energy to melt the ice. If there had been more ice (relative to the rock), there would not have been enough heat generated and less ice would have melted,” Shugar added.

By analysing the videos, they reconstructed the flow was 25 metre per second (m/s) near the Rishiganga hydropower project (15km downstream from avalanche source), 16m/s just upstream of the Tapovan project (10km downriver) and 12m/s just downstream of Tapovan (26km from source), while the average between Raini and Joshimath (16km downstream) was 10m/s. The study also estimated the mean discharge from the videos — 8,200-14,200 cubic metre per second (m3/s) at the Rishiganga project and 2,900-4,900 m3/s at the Tapovan project. Rashid said, “The maximum flood heights in certain river valley areas touched ~100 m, which is something that none of the team members had expected.”

Because the flow was highly mobile, another anomaly occurred. “Notably, and in contrast to most previously documented rock avalanches, very little debris is preserved at the base of the failed slope,” the paper said. As the flow turned more fluid downvalley, there were “remarkably few large boulders that typically form the upper surface of rock avalanches.”

But one of the primary drivers of the disaster, the paper said, was “the unfortunate location of multiple hydropower plants in the direct path of the flow.” Co-author Dr Mohd Farooq Azam from IIT-Indore told TOI, “The greater magnitude of the latest Chamoli disaster is an argument in favour of avoiding further developments in the fragile mountains of the Himalaya.” The paper concluded, “The disaster tragically revealed the risks associated with the rapid expansion of hydropower infrastructure into increasingly unstable territory.”

Why in February?

Ishita Mishra, February 8, 2021: The Times of India

Why did glacier break in cold winter month of Feb?

DEHRADUN: It's winter. February temperatures can drop to below zero in the hills of Uttarakhand's Chamoli and summer is a long way off. Why, then, did a glacier break off, with disastrous effect? Geologists who have been studying the region's glaciers said climate change is to blame.

"This is an anomaly. In winter, glaciers remain firmly frozen. Even walls of glacial lakes are tightly bound. A flood of this sort in this season is usually caused by an avalanche or landslide. Neither seems to be the case here," Manish Mehta, senior scientist at Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, told TOI. He could not immediately recall a precedent.

Mehta had led a study last year which found that the eight glaciers of the upper Rishiganga catchment - Uttari Nanda Devi, Changbang, Ramni Bank, Bethartoli, Trishul, Dakshni Nanda Devi, Dakshni Rishi Bank and Raunthi Bank - had lost over 10% of their mass in less than three decades. From 243 sq km in 1980, they had shrunk to 217 sq km in 2017, with Uttari Nanda Devi receding the most (7.7%). The upper Rishiganga catchment is where the glacier burst took place on Sunday.

In the same period, the equilibrium line altitude (the zone on a glacier where its mass lost is balanced by its mass gained over a year) fluctuated a lot - between 5,200m above sea level and 5,700m. "It does not change if climate conditions are consistent," MPS Bisht, director of the Uttarakhand Space Application Centre, which was also part of the study along with IIT-Kanpur and HNB Garhwal University, said.

Himalayan glaciers have been retreating faster than anywhere else in the world. "Yet, the state of glacier response (how much it retreats or advances) has not been studied extensively. So, we mapped the variations of extent and dynamics of the glaciers in the upper Rishiganga catchment, Nanda Devi region and found most glaciers have been shrinking," Mehta said.

This has been pronounced since the 1990s. "We found south-facing glaciers receded faster than north-facing ones, possibly because of longer exposure to insolation (solar radiation). How glaciers respond to climate is also dependent on its size and geometry."

Because the glaciers are of the "winter accumulation type," a decrease in precipitation may have caused this, the study said. "The equilibrium line altitude swing suggests glaciers in the region have responded to deprived precipitation conditions since 1980," Bisht said. And while temperatures have been increasing since the 1980s, the study said, the glaciers are more sensitive to changes in precipitation. The larger context, however, is that of increased global temperatures. Mehta said, "Against the backdrop of warming since the mid-1990s, accelerated glacial reduction could be correlated with increased global temperature."

2019, PIL flagged firm’s ‘hazardous practices

Prashant Jha, February 8, 2021: The Times of India

The Rishiganga hydroelectric power project had been red-flagged by local villagers as an “impending disaster”. In 2019, a village resident named Kundan Singh had filed a PIL in the Uttarakhand HC alleging unfair and environmentally hazardous practices by the private firm involved in the project. It was alleged that the firm was “using explosives and blasting the mountains for mining”. The blasting, the petition said, had damaged the sensitive areas around the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve.

Singh had said that all the waste material from the project was being dumped into the Rishiganga river, adding that despite complaints from the villagers, no action was taken. “Moreover, it was also noticed that the blatant stone crushing activity was being carried out on the riverbed, flouting all norms that the government had laid down for stone crushing activity in this area,” Singh said his petition.

Based on the PIL, the court had observed that use of explosives may “result in destruction of the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, and the Valley of Flowers”. Therefore, the court banned the use of explosives in the area, and in June 2019, directed the member secretary of the pollution control board and the district magistrate to constitute a joint inspection team and visit the site.

However, the report, a copy of which is available with TOI, exonerated the firm and said that it found no proof of illegal mining or blasting.However, the court was informed that there still was some muck around the barrage and power house. On July 26, the court had listed the case for further hearing in August. There hasn’t been a single hearing after that and the case is still pending.

The events

How the glacier was struck

Ishita Mishra & Rohan Dua, February 10, 2021: The Times of India

A fivemember team of scientists deployed by the Centre to establish the chain of events that led up to the Uttarakhand flood on Sunday has found that a peak that “came loose” and a glacier perched precariously atop a cliff are most likely to have triggered the disaster.

The team from the Dehradun-based Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology (WIHG) trekked to the glacial site in Uttarakhand’s Chamoli district and conducted field and aerial surveys on Tuesday. “The initial conclusion we’ve drawn is that Sunday’s incident was an episodic failure of rock mass (rockslide) and hanging glacier (that stops midway down a cliff) in the Raunthi glacier area,” WIHG director Kalachand Sain told TOI.

The origin was around two peaks — Raunthi and Mrigthuni. “It is possible a peak, a heavy and solid structure, broke off because of natural causes and fell on to a glacier beneath it, some 5,600m above sea level,” Sain said. That, in turn, fragmented the glacier and chipped off pieces were consolidated with the rock debris.

The rock-avalanche then surged over a sharp 37° slope for about 3km before hitting the Raunthi Gadhera stream’s floor at an altitude of about 3,600m. When it hit the river bed, the mix of heavy objects created a dam-like structure that stayed in place for some time because it was snowing. In the report, the scientists have attached photos of the accumulated water and those from September 28 last year, when it wasn’t present.

Then, for three days before the flood, the weather had been clear. “This caused freezing and thawing, leading to a massive slope failure,” the preliminary report said. Which means that the rock-ice mix that had accumulated melted, breached the area and came surging down to hit Tapovan Valley. “The flow contained rocks, snow, water,” said Sain. And the force it took on was because of this heavy mix, a scientist who prepared the report said. The downhill surge also generated heat, which may have melted the ice in the mix and added to the volume. A large part of what happened now understood, scientists are trying to figure out the root cause — what made the peak break off ?

“We believed the area the rock fell from had developed a weak zone. That happens only over a course of several years — it’s not the instant result of weather disturbance, like cloudburst or rains, as was the case with the 2013 floods. What we saw took decades to happen,” Sain said. “Continuous monitoring of glaciers — India has 26 — is vital. It could help avert such disasters, plan for remedial measures.”

The flood was initially believed to have been caused by a glacial lake outburst, when a glacial lake flows over. But satellite images from Indian Institute of Remote Sensing, shared with the Uttarakhand disaster management and mitigation centre on Monday, showed a landslide was more likely to have triggered the flood.

The Centre, taking Tuesday’s findings into account, said the probe will continue. Department of science and technology secretary Prof Ashutosh Sharma said, “This will be explored to ensure it’s helpful in managing our natural assets in the future.”

Behaviour of fish

Kautilya Singh & Shivani Azad, February 10, 2021: The Times of India

Did fish sense the oncoming deluge?

An otherwise slow Sunday morning in Lasu village was disrupted by a strange occurrence — the Alaknanda river, by which it lies, had turned silver with shoals of fishes close to the surface. It was around 9am. Within minutes, some hundred locals had gathered, ready with baskets, buckets, pots, pans to “pick up” the fish — they didn’t even have to drop a rod or net.

What they could not have known was that about 70km upstream, in another hour or so, disaster was about to strike. And this was a precursor.

In Raini, the surging Dhauliganga would ravage everything in its path after a landslide-triggered avalanche flooded it. The Dhauliganga is the Alaknanda’s tributary. And those downstream from the river, in places far away from Raini — Nandprayag, Langasu, Karnprayag — saw what those at Lasu had seen. Innumerable mahseers, carps and snow trouts had filled the waters, were not swimming too deep inside and were sticking to the banks. “Fish always swim in the middle of the stream. It was abnormal. They were only swimming along the edges,” Ajay Purohit, one of the first to spot the fish, told TOI.

At Girsa village, near Langasu, surprise gave way to pragmatism. “At least one person from each family in our village went to see what was happening. On any day, it would not be possible to catch fish with our hands. But they were so close, and so many. All of us brought back a lot of fish,” said Radha Krishna, a resident. Some of the fish caught weighed up to 2kg.

The one change they may have missed was that of the water. The clear green had turned grey, just like the slurry that had washed over Raini, Tapovan and other villages flooded in Chamoli.

How are the two related? Scientists said the subsurface vibrations of whatever it is that caused the floods may have ‘broken the sensors’ of fish upstream.

“Fish have a lateral line organ (a biological system in aquatic creatures that help them detect movement and pressure changes in water). It’s very sensitive. The slightest disturbance can set it off, sending the fish into a state of shock,” said K Sivakumar, senior scientist at Wildlife Institute of India. “In this case, it’s possible that a sound preceding the flood may have been picked up by the fish. It is also possible an electric wire or some source of power fell into the water and gave them electric shocks. There can be many reasons. This is why we keep saying that dynamite blasting should never be done on a river.”

After effects

Flora, fauna

Shivani Azad, February 16, 2021: The Times of India

A preliminary digital analysis of the Nanda Devi National Park revealed extensive damage to flora and fauna of the sanctuary, a Unesco World heritage site, caused by the flash flood. Forest officials said that Raunthi area, the core zone of the national park, had been badly hit.

Also, according to experts of the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology (WIHG) as well as other institutes studying reasons behind the flood, the water had further damaged a 22km stretch from Raunthi to Tapovan. The current had sliced off a side of the mountain, sweeping away trees, medicinal herbs, shrubs, endangered species like musk deer, Himalayan goats as well as leopards.

“The preliminary digital analysis, done by expert scientists, shows around 200 hectares of the forest has been lost. In terms of area, the losses can amount to several lakhs, as it was the habitat of precious trees and animals — Himalayan birch, Pindrow Fir, Surai, Kaangar and Kael as well as musk deer, Himalayan goats, bharals, and leopards,” said range officer of Vijay Lal Arya. A forest team will give its final report by the end of this week, said DFO of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve NB Sharma. “The team is yet to reach the actual spot, as there is no connectivity,”he said.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, officials of the forest department said that “the loss in monetary terms may turn out to be immense after an adequate evaluation is done”. An official said, “The area is among some of the rarest in the Himalayan zone and its flora and fauna has been devastated.”

New lake: a danger

Ishita Mishra, February 12, 2021: The Times of India

‘New’ lake formed, poses danger: Experts

Dehradun:

Geologists of the Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Garwal University (HNBGU) who are conducting a survey of the Rishiganga area — from where the flash floods started on Sunday — have said a water body has formed near the Rishiganga which can cause floods again.

This revelation came even as water levels of the Rishiganga, which was flowing as a small channel on a stretch near the disaster site for the past four days, rose on Thursday, leading to a temporary halt in rescue operations and an alert being issued to villagers in the area.

In a video that he released, with the hope that authorities see it and are aware of the potential threat, professor Naresh Rana from the earth sciences department of HNBGU can be seen pointing at what he termed “a blue-coloured lake” that had formed near the Rishiganga. “I am here at a peak from where I can see the Raunthi and the Rishiganga streams clearly. It seems the flash floods have come from the Raunthi stream. The flood created a temporary dam and because of this dam the Rishiganga is still blocked. I can also see a blue-coloured lake having formed in the distance, which means that water has been ponding here since long. This ponding is very stable and hence I can assume that this lake extends far. From the point I am standing, however, I cannot see its full extent,” he says in his video.

Rana added that the formation of the lake is a serious matter as “this means the Rishiganga will breach again and this can impact rescue operations too”.

Confirming the formation of a water body upstream of the Rishiganga, Kalachand Sain, director of Dehradun-based Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology (WIHG), said water accumulation was seen after an aerial view of the region was recorded by a WIHG team that is presently at the spot. “We cannot say as of now whether that water accumulation has triggered the current rise in the level of the Rishiganga or Dhauliganga. I am yet to get the details of the size of the pond and reason of its formation. This can either be a new lake or an old one,” he said.

See also

Glacier bursts: Chamoli