Fundamental rights: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The Rights

Shobita Dhar , January 26, 2020: The Times of India

Get to know your fundamental rights

Equality, secularism and rule of law are not the gift of any government, they are rights that Indian citizens give to themselves under the Constitution. The fundamental rights in the Constitution span the right to equality, right against exploitation, right to freedom of religion, cultural and educational rights, and the right to constitutional remedies…

Articles 14-18 | Deal with equality before the law, which applies to all persons regardless of race, nationality or colour, within the territory of India. The state cannot discriminate on the basis of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. However, the focus is on substantive equality, so the state can make special provisions for women, or any socially or educationally backward classes of citizens, scheduled castes or tribes.

Articles 19-22 | Lay out the freedoms guaranteed to every citizen, and the specific conditions where the state can restrict individual liberty. These freedoms include the freedom of speech and expression, freedom of assembly, freedom to form associations, freedom of movement, to reside and settle, and freedom of profession, occupation, trade and business.

Article 21 | The right to life and liberty, has been interpreted to strengthen human dignity and due legal process, including livelihood, health, education, environment and humanitarian treatment in prison. The right to property was removed as a fundamental right in 1978, and the right to privacy has been recently added. There are safeguards against arbitrary arrest and detention.

Articles 23-24 | Deal with the right against exploitation.

Articles 25-28 | Articulate freedom of religion in a secular state that respects all religions equally. It guarantees freedom of conscience and the right to profess, propagate religion. Article 26 deals with the management of religious affairs, subject to conditions of public order, morality and health. Article 28 disallows religious instruction in wholly state-run educational institutions.

Articles 29-30 | Protect the interests of minorities. Since electoral democracy rests on majority consensus, the Constitution explicitly lays out the rights of minorities to protect against discrimination. It allows religious and linguistic minorities to conserve their language, culture and educational institutions, subject to reasonable regulation by the state.

Articles 32-35 | Deal with the remedies for any violation of these constitutional rights. This means the right to move the Supreme Court and its power to issue writs to enforce fundamental rights, and that only Parliament has the right to make laws that give effect to these fundamental rights. Also, the basic structure doctrine laid out by the Supreme Court means that this set of core, inviolable ideals of the Constitution cannot be damaged or altered by Parliament, and that the Supreme Court remains the arbiter of all amendments.

Entitlement to fundamental rights

Only law-abiding citizens can claim fundamental rights: SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra, May 25, 2022: The Times of India

New Delhi: At a time when objectionable social media posts are circulated with impunity by sheltering behind the right to free speech, the Supreme Court has ruled that the shield of this fundamental right is available only to those who adhere to law and respect legal processes. A bench of Justices Dinesh Maheshwari and Aniruddha Bose last week ruled that “any claim towards fundamental rights cannot be justifiably made without the person concerned himself adhering to and submitting to the process of law”. Though this ruling came in acase where an accused, who had challenged invocation of anti-gangster law MCOCA by the Maharashtra government, the general nature of the ruling by the court has far reaching spillover implications on awhole gamut of cases. The accused had challenged invocation of the stringent anti-gangster law against him and had pleaded that it would have serious impact on his fundamental rights, a whole range of which would still be available to an accused facing charges under the IPC. Writing the judgment, Justice Maheshwari said, “As regards the implication of (MCOCA) proclamation having been issued against the appellant, we have no hesitation in making it clear that any person who is declared an absconder and remains out of reach of investigating agencies and thereby stands directly at conflict with law, ordinarily, deserves no concession or indulgence. ”

As an illustration, the bench said an ordinary accused had the liberty to resort to Section 438 of Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) to approach any court to seek anticipatory bail. “But when an accused is absconding and is declared as proclaimed offender, there is no question of giving him the benefit of Section 438 of CrPC,” the bench said.

“What has been observed and said in relation to Section 438 CrPC applies with more vigour to the extraordinary jurisdiction of this court under Article 136 of the Constitution of India. The submissions on behalf of the appellant for consideration of his case because of application of stringent provisions impinging his fundamental rights does not take away the impact of the blameworthy conduct of the appellant. Any claim towards fundamental rights also cannot be justifiably made without the person concerned himself adhering to and submitting to the process of law,” the bench said.

The accused appellant was challenging an order of the Nagpur bench, Bombay High Court, upholding the Nagpur City additional director general of police to invoke provisions of Maharashtra Control of Organised Crimes Act (MCOCA) against him and others on the ground that they together have been indulging in violence and threatening people either for monetary gain or to establish their supremacy in the world of crime.

The bench perused the crime chart against the accused, nature of their activities and the persons involved and said it left “nothing to doubt that the involvement of the appellant in such crimes and unlawful activities which are aimed at gaining pecuniary advantages or of gaining supremacy and thereby, leading to other unwarranted advantages is clearly made out”.

Post emergency: Expansion of fundamental rights

The Times of India, Jun 29 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

A little over 40 years ago on June 12, 1975, Justice Jag mohan Lal Sinha of Allahabad high court inflicted a stinging moral and mental blow to then PM Indira Gandhi. The HC annulled her election to Lok Sabha from Rae Bareli, taking away her authority to remain PM. She appealed in the Supreme Court. Celebrated lawyer Nani Palkhivala argued for interim relief before Justice Krishna Iyer on June 23, 1975.

Palkivala later wrote, “The interim order (passed on June 24, 1975) was that pending the hearing and final disposal of the appeal, Mrs Gandhi could continue to sit in the Lok Sabha and participate in the proceedings of that House like any other member. The only restriction on her was that she was not given the right to vote.

“The judge mentioned that this did not involve any hardship because Parliament was not in session at the time and that I (Palkhivala) could renew the application for the right to vote when Parliament re-assembled. The evening of that very day (June 24, 1975), I saw Mrs Gandhi at her residence and told her that I found the interim order very satisfactory and she should not worry about the case since the judgment of the trial court did not seem to be correct on the recorded evidence.“

He further said, “In less than 36 hours, Emergency was declared, invaluable fundamental rights of the people were suspended, and the PM virtually acquired all the powers of the leader of a totalitarian state. That was the black morning of June 26, 1975.“

What followed were dreadful days of Emergency . Overnight, protectors turned predators.They wantonly inflicted misery on citizens and settled personal scores. With impunity , they butchered fundamental rights of citizens and threw them into prison even for a murmur of protest.

Elected representatives either sided with the authoritarian ruler, went underground or were jailed. The citizens' sole refuge was the judiciary . Preventive detentions under Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) were challenged in high courts through habeas corpus writs.

Fali S Nariman recounted in his autobiography `Before Memo ry Fades', “Nine high courts in the country , including the high courts of Allahabad, Bombay , Delhi, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana, held that notwithstanding the imposition of Emergency and the Presidential Order, courts were empowered to examine whether orders of detention were in accordance with MISA under which detenus were detained.“

The HCs upheld the rule of law and those judges stood by their oath. The Centre and state governments challenged these HC decisions in the Supreme Court, the lead one being the infamous `ADM Jabalpur' case.

If the majority in bureaucracy and police either enjoyed the draconian power or acquiesced to implement patently illegal orders, four of the five judges of the SC in ADM Jabalpur case displayed lack of spine and delivered a skewed judgment -that even the most important right to life could be suspended during Emergency .

Those who lost their spine to the terror of Emergency and fear of Mrs Gandhi were then Chief Justice A N Ray and Justices M H Beg, Y V Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati. Standing upright against these four was the diminutive Justice Hans Raj Khanna, who in his dissenting judgment said come what may , right to life could never be suspended by a government order.

Soon after lifting of Emergency and India limping back to democracy , those judges who had succumbed to authoritarian terror quickly got back on the track of justice. Within years of ADM Jabalpur, they authored landmark judgments -Maneka Gandhi and Minerva Mills -eulogizing the preciousness of right to life and how life did not mean mere animal existence. Probably , these were judgments of repentance! So, Emergency did have some sobering effect on the highest judiciary , resulting in expansion of fundamental rights, especially the right to life, and giving them a cloak of inviolability . It is difficult to say whether these judgments would have been delivered had Emergency continued for a few more years.

BJP patriarch L K Advani often used to take a dig at journalists because of the lack of spine shown by their tribe during the troubled days by asking, “When they asked you to just bend, why did you crawl?“ But many did stand up to the tyranny and protested loudly .

Advani recently dreamt of the ghost of Emergency and said he could feel the stirring of demonic tendencies towards authoritarian rule. Most anti-BJP political leaders agreed with Advani. But finance minister Arun Jaitley ruled out return of Emergency , saying present day rapid communication networks were the best guard against authoritarian rule.

But during Emergency , India experienced the crumbling of elected representatives, bureaucracy , police and judiciary . So what could be the unshakable anchor for democracy when a seasoned politician like Advani expresses apprehensions? One can take solace in the words of Sachchidananda Sinha, who was provisional chairman, in the first session of Constituent Assembly on December 9, 1946, “(The Constitution) has been reared for immortality , if the work of man may justly aspire to such a title. It may , nevertheless, perish in an hour by the folly or corruption, or negligence of its only keepers, the people.“

B: SPECIFIC ISSUES

Arrest, grounds of, have to be communicated/ SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra, May 16, 2024: The Times of India

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra, May 16, 2024: The Times of India

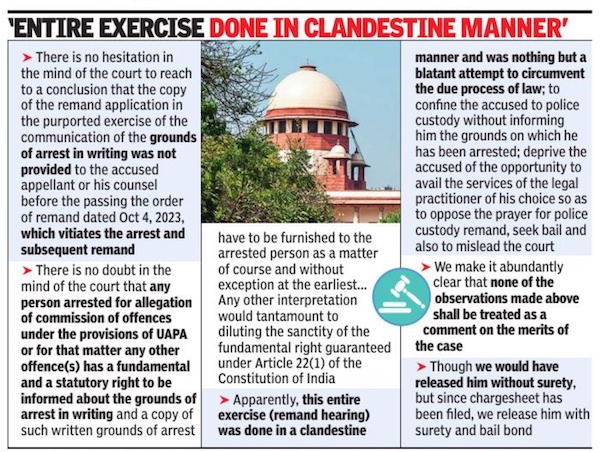

New Delhi : Following the SC order finding the arrest and remand of NewsClick founder and editor-in-chief Prabir Purkayastha illegal, Patiala House Court ordered his release on bail bonds worth Rs 1 lakh, and on three conditions — he shall not contact witnesses and approvers in the case, he shall not talk about the merits of the case and he shall not travel abroad without the court’s permission. Purkayastha was arrested by Delhi Police on Oct 3 along with NewsClick’s HR head Amit Chakraborty for allegedly receiving illegal funding from China, routed through US with the intention of undermining India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Writing the 41-page SC judgment, Justice Sandeep Mehta said Purkayastha’s arrest, followed by the remand order of Oct 4 last year and Delhi HC’s Oct 15 order validating the remand, were contrary to law and hence quashed. Non-intimation of grounds of arrest to Purkayastha and his counsel vitiated the arrest and remand order, he said.

“There is no doubt in the mind of the court that any person arrested for allegation of commission of offences under provisions of UAPA or for that matter any other offence(s) has a fundamental and statutory right to be informed about the grounds of arrest in writing and a copy of such written grounds of arrest has to be furnished to the arrested person as a matter of course and without exception at the earliest,” the bench, which also comprised Justice B R Gavai, said. It turned down the argument of ASG S V Raju, and said the SC order in Pankaj Bansal case regarding the rights of the accused under PMLA — to be informed of the grounds of arrest in writing — applied also to those charged with offences under UAPA.

“The purpose of informing the arrested person (of) the grounds of arrest is salutary and sacrosanct inasmuch as this information would be the only effective means for the arrested person to consult his advocate, oppose the police custody remand and seek bail,” SC said.

Elaborating on the mandatory duty of police to give written information on grounds of arrest, Supreme Court said it must inform the arrested person of “all basic facts on which he was being arrested” so as to provide him an opportunity to defend himself against custodial remand and to seek bail. “Thus, the ‘grounds of arrest’ would invariably be personal to the accused and cannot be equated with the ‘reasons of arrest’ which are general in nature,” it said.

“Right to life and personal liberty is the most sacrosanct fundamental right guaran- teed under Articles 20, 21 and 22 of the Constitution. Any attempt to encroach upon this fundamental right has been frowned upon by this court in a catena of decisions… Thus, any attempt to violate such a fundamental right, guaranteed by Articles, 20, 21 and 22 of the Constitution, would have to be dealt with strictly,” it said. The apex court said the FIR copy was not provided to Purkayastha despite him making an application. The copy of the FIR was provided to him on Oct 5 last year, two days after he was arrested and a day after he was remanded in police custody, the court said.

Pursuing private claims abroad

Government has no obligation to pursue private claims abroad

Dec 05 2016: The Times of India

`Govt has no obligation to pursue pvt claims abroad'

The government has no obligation to pursue private claims of an Indian citizen over a dispute abroad, the Delhi high court has said. HC rejected the plea of the widow of a freedom fighter who sought return of money deposited by her husband in a Chinese post office when he served in Subhash Chandra Bose's Indian National Army.

She wanted the money that her husband deposited as savings in Shanghai, she told the court, but HC maintained that the government can't be forced to pursue her claims.

“We are of the view that merely because the Government of India, on a representation being made, has for warded the claim of the petitioner to the Embassy of India at China, would not create an obligation on the Government of India to take any further steps in the matter,“ a bench of Chief Justice G Rohini and Justice Sangita Dhinra Sehgal observed.

The court further added, “The Government of India is under no obligation to raise a dispute with a foreign government qua the private claim of its citizens,“ dismissing an appeal filed by Harbhajan Kaur, the widow of the INA officer who died in 1979. Earlier a single judge had also rejected her plea for direction to the government to take ap propriate action for releasing the money deposited by her late husband in his accounts with Shanghai's General Post Office.

The Shanghai post office, in a letter to Kaur, made it clear that her claim stood abandoned for failing to register it within the assigned time after the issuance of the new policy of the Chinese government.

The single judge had declined relief on the ground that as on December 2015, her “petition is also highly belated“. Double bench affirmed the finding and noted that Kaur “was unable to provide us with any specific obligation under which the government has to pursue private claims of petitioner against a foreign government“.

Self-incrimination, right against/ Article 20 of Constitution

Accused can be ordered to give voice sample: SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra, August 3, 2019 The Times of India

Accused can be ordered to give voice sample: SC

New Delhi:

In a landmark verdict that fills a vacuum in the Criminal Procedure Code, the Supreme Court on Friday ruled that a person can be compelled to give voice sample for crime probe and it will not violate his fundamental right against self-incrimination guaranteed under Article 20 of the Constitution.

A bench of CJI Ranjan Gogoi and Justices Deepak Gupta and Sanjiv Khanna used the discretionary power for “doing complete justice” to empower magistrates to ask an accused to give voice sample for crime probe, due to uniqueness of a person’s voice, which is akin to fingerprints.

SC exercises power under Art 142 for voice sample ruling

An SC bench of Justices Aftab Alam and Ranjana Desai had on December 7, 2012, returned a split verdict on whether a magistrate, without specific provisions under the CrPC, could be empowered by the SC through judicial interpretation to direct an accused to provide her/his voice sample to police. Nearly seven years later, the bench headed by CJI Ranjan Gogoi said, “We unhesitatingly take the view that until explicit provisions are engrafted in the CrPC by Parliament, a judicial magistrate must be conceded the power to order a person to give a sample of his voice for the purpose of investigation of a crime.”

Writing the unanimous judgment for the three-judge bench, the CJI said, “Such power has to be conferred on a magistrate by a process of judicial interpretation and in exercise of jurisdiction vested in the Supreme Court under Article 142 of the Constitution.” CJI Gogoi said medical examination of an accused was getting wider meaning given the advancement of technology and cited the amendments carried out in the CrPC which allowed medical examination of the accused and the mandate to a person to provide handwriting specimen for investigation of a crime. The bench conceded that the legislature had not yet framed a law relating to voice samples.

The case related to an FIR lodged on December 7, 2009, by the Sadar Bazar police station in UP’s Saharanpur district alleging that one Dhoom Singh, in association with one Ritesh Sinha, was collecting money from people on the promise of jobs in the police department.

Passwords

January 4, 2024: The Times of India

‘Accused can’t be coerced to reveal passwords of gadgets’

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

New Delhi : Delhi High Court recently said an accused couldn’t be coerced to reveal the passwords of his gadgets and online accounts in view of the protection guaranteed under Article 20(3) — right against self-incrimination — in the Constitution.

The single-judge bench of Justice Saurabh Banerjee made the observation while granting bail to an accused in a case in which it had been alleged that a private company and its directors had made about $20 million by making scam phone calls to American citizens from fraud call centres in India. While stating that any accused like the applicant is expected to show high sensitivity, diligence and understanding during such an investigation, the court also observed, “At the same time, the investigating agency cannot expect anyone who is an accused to sing in a tune which is music to their ears, more so, whence such an accused, like the applicant herein, is well and truly protected under Article 20(3) of the Constitution of India.”

CBI had opposed the bail plea, saying that the accused, a director of the company, was the kingpin of the scam and had failed to provide the pass words for his gadgets, email and crypto wallet accounts.

The counsel for the accused submitted that out of the 12 accused, only the applicant was arrested and the investigation against him was complete. Noting that those who were allegedly cheated stayed abroad, the judge said there were minuscule chances of the accused influencing them.